USS Massachusetts (BB-2)

._Starboard_bow_at_wharf%2C_06-1901_-_NARA_-_535432.tif.jpg) Massachusetts in 1901 | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Massachusetts |

| Namesake: | State of Massachusetts |

| Ordered: | 30 June 1890 |

| Builder: | William Cramp & Sons, Philadelphia |

| Yard number: | 271 |

| Laid down: | 25 June 1891 |

| Launched: | 10 June 1893 |

| Sponsored by: | Leila Herbert |

| Commissioned: | 10 June 1896 |

| Decommissioned: | 8 January 1906 |

| Recommissioned: | 2 May 1910 |

| Decommissioned: | 23 May 1914 |

| Commissioned: | 9 June 1917 |

| Renamed: | Coast Battleship Number 2 29 March 1919 |

| Decommissioned: | 31 March 1919 |

| Struck: | 22 November 1920 |

| Identification: | Hull symbol: BB-2 |

| Fate: | Scuttled 6 January 1921 |

| Status: | Artificial reef and diving site |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: | Indiana-class pre-dreadnought battleship |

| Displacement: | 10,288 long tons (10,453 t) standard[1] |

| Length: | 350 ft 11 in (107.0 m)[1] |

| Beam: | 69 ft 3 in (21.1 m)[1] |

| Draft: | 27 ft (8.2 m)[1] |

| Installed power: |

|

| Propulsion: |

|

| Speed: | 15 knots (28 km/h; 17 mph) (design)[2] |

| Range: | 4,900 nmi (9,100 km; 5,600 mi)[lower-alpha 1][4] |

| Complement: | 473 officers and men[5] |

| Armament: |

|

| Armor: | |

|

USS Massachusetts (BB-2) | |

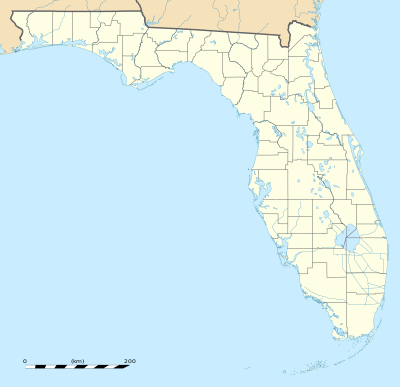

| |

| Location | Escambia County, Florida, USA |

| Nearest city | Pensacola, Florida |

| Coordinates | Coordinates: 30°17′49″N 87°18′41″W / 30.29694°N 87.31139°W |

| Area | less than one acre |

| NRHP reference # | 01000528[6] |

| FUAP # | 4 |

| Added to NRHP | 31 May 2001 |

USS Massachusetts (BB-2) is a diving site and was a Indiana-class battleship and the second United States Navy ship comparable to foreign battleships of the time.[7] Authorized in 1890 and commissioned six years later, she was a small battleship, though with heavy armor and ordnance. The ship class also pioneered the use of an intermediate battery. She was designed for coastal defense and as a result, her decks were not safe from high waves on the open ocean.

Massachusetts served in the Spanish–American War (1898) as part of the Flying Squadron and took part in the blockades of Cienfuegos and Santiago de Cuba. She missed the decisive Battle of Santiago de Cuba after steaming to Guantánamo Bay the night before to resupply coal. After the war she served with the North Atlantic Squadron, performing training maneuvers and gunnery practice. During this period she suffered an explosion in an 8-inch gun turret, killing nine, and ran aground twice, requiring several months of repair both times. She was decommissioned in 1906 for modernization.

Although considered obsolete in 1910, the battleship was recommissioned and used for annual cruises for midshipmen during the summers and otherwise laid up in the reserve fleet until her decommissioning in 1914. In 1917 she was recommissioned to serve as a training ship for gun crews during World War I. She was decommissioned for the final time in March 1919 under the name Coast Battleship Number 2 so that her name could be reused for USS Massachusetts (BB-54). In 1921 she was scuttled in shallow water in the Gulf of Mexico off Pensacola, Florida, and then used as a target for experimental artillery. The wreck was never scrapped and in 1956 it was declared the property of the State of Florida. Since 1993 the wreck has been a Florida Underwater Archaeological Preserve and it is included in the National Register of Historic Places. It serves as an artificial reef and diving spot.

Design and construction

.jpg)

Massachusetts was constructed from a modified version of a design drawn up by a policy board in 1889 for a short-range battleship. The original design was part of an ambitious naval construction plan to build 33 battleships and 167 smaller ships. The United States Congress saw the plan as an attempt to end the U.S. policy of isolationism and did not approve it, but a year later approved funding for three coast defense battleships, which would become Massachusetts and her sister ships Indiana and Oregon.[8] The ships were limited to coastal defense due to their moderate endurance, relatively small displacement and low freeboard, or distance from the deck to the water, which limited seagoing capability.[9] They were however heavily armed and armored; Conway's All The World's Fighting Ships describes their design as "attempting too much on a very limited displacement."[10]

Construction of the ships was authorized on 30 June 1890 and the contract for Massachusetts—not including guns and armor—was awarded to William Cramp & Sons of Philadelphia, who offered to build it for $3,020,000.[11] The total cost of the ship was almost twice as high, approximately $6,000,000.[12] The contract specified the ship had to be built in three years, but slow delivery of armor plates and guns caused a delay.[13] Her keel was laid down on 25 June 1891[12] and she was launched two years later on 10 June 1893. The launching ceremony was attended by thousands of people, including Secretary of the Navy Hilary A. Herbert and commander George Dewey.[14] Her preliminary sea trial did not take place until March 1896 because of the delays in armor and gun deliveries. At this point Massachusetts was almost complete,[13] and her official trial was held a month later.[15]

Service history

Early career

Massachusetts was commissioned on 10 June 1896 with Captain Frederick Rodgers in command. She had her shakedown cruise between August and November 1896, followed by an overhaul at the New York Navy Yard. In February 1897 she made a short voyage to Charleston, South Carolina. The battleship departed New York again in May for Boston, where a celebration in her honor was held. For the next ten months the warship participated in training maneuvers with the North Atlantic Squadron off the coast of Florida and visited several major ports on the American east coast. On 27 March 1898, she was ordered to Hampton Roads to join the Flying Squadron under Commodore Winfield Scott Schley for the blockade of Cuba.[16]

Spanish–American War

%2C_Antonio_Jacobsen.jpg)

After the outbreak of the Spanish–American War the Flying Squadron steamed to Key West. There Schley met with Rear Admiral Sampson, who had just returned from the bombardment of San Juan, Puerto Rico. They discussed the possible locations of the Spanish squadron under Admiral Cervera, and Schley was sent to the harbor of Cienfuegos, Cuba to look for Cervera.[17] Schley arrived off Cienfuegos on 22 May and took several days to establish that Cervera's ships were not in the harbor. The squadron then proceeded to Santiago de Cuba, the only other port on the southern coast of Cuba large enough for the Spanish ships,[18] arriving after several delays on 29 May.[19] On arrival, the Spanish cruiser Cristóbal Colón was visible from outside the harbor entrance, confirming that the Spanish fleet was in the harbor.[20] Schley blockaded the harbor and informed Sampson, who arrived with his own squadron on 1 June[21] and assumed overall command.[22]

During the next month Massachusetts took part in the blockade of Santiago, occasionally bombarding the harbor forts.[16] On the night of 2–3 July she and the two cruisers New Orleans and Newark left the blockade to load coal in Guantanamo Bay.[23] This caused her to miss the Battle of Santiago de Cuba on 3 July, in which the Spanish fleet attempted to break through the blockade and was completely destroyed.[24] The next day the battleship came back to Santiago, where she and Texas fired at the disarmed Spanish cruiser Reina Mercedes, which was being scuttled by the Spanish in an attempt to block the harbor entrance channel.[25] Massachusetts was then sent to Puerto Rico to support the American occupation until she steamed home to New York on 1 August, arriving on 20 August.[16]

Post Spanish–American War

After a quick overhaul in drydock, Massachusetts was attempting to leave New York Harbor on 10 December 1898 when she struck Diamond Reef, flooding five of her forward compartments. She was forced to return to the navy yard, where she was placed in drydock again for repairs which took around three months.[26][27] For a year Massachusetts served with the North Atlantic Squadron, visiting various cities on the Atlantic coast.[16] In May 1900, she and Indiana were placed in reserve as the navy had an acute officer shortage and needed to put the new Kearsarge-class and Illinois-class battleships into commission.[28] The battleships were reactivated the following month as an experiment in how quickly this could be achieved,[29] and Massachusetts returned to service with the North Atlantic Squadron.[16]

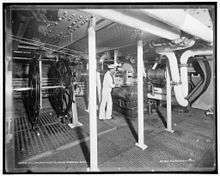

In March 1901 the battleship grounded again, this time in the harbor of Pensacola, Florida,[30] but the ship was able to continue her trip.[31] A more serious accident occurred during target practice in January 1903, when an explosion in an 8-inch turret killed nine crew members. They were the first fatalities aboard a United States battleship since the sinking of the Maine.[32] Another accident happened in August of that year, when Massachusetts grounded on a rock in Frenchman Bay, Maine. The ship was seriously damaged and had to be repaired in drydock.[33] In December 1904 yet another lethal accident took place aboard Massachusetts: three men were killed and several others badly burned when a broken gasket caused steam to fill the boiler room.[34] On 8 January 1906 the battleship was decommissioned and her crew was transferred to her sister ship Indiana, which had completed a three-year modernization. Massachusetts now received the same upgrades,[35] including twelve 3"/50 caliber gun single-purpose guns to replace the 6-inch and most of the lighter guns, new Babcock & Wilcox boilers, counterweights to balance her main turrets, a lattice mast and electric traversing mechanisms for her turrets.[36]

On 2 May 1910 Massachusetts was placed in reduced commission so she could be used for the annual Naval Academy midshipmen summer cruise.[16] Despite her modernizations the battleship was now regarded as "obsolete and worthless, even for the second line of defense" by Secretary of the Navy George von Lengerke Meyer.[37] She saw little use other than summer cruises and was transferred to the Atlantic Reserve Fleet when it was formed in 1912.[38] After a quick trip to New York for a Presidential Fleet Review in October 1912, the warship returned to Philadelphia and stayed there until she was decommissioned on 23 May 1914.[16]

World War I and later

After the United States entered World War I Massachusetts was recommissioned for the final time on 9 June 1917. She was used by Naval Reserve gun crews for gunnery training in Block Island Sound until 27 May 1918. The battleship was then redeployed to serve as a heavy gun target practice ship near Chesapeake Bay until the end of World War I. Massachusetts returned to Philadelphia on 16 February 1919. She was decommissioned for the final time on 31 March 1919, after being re-designated "Coast Battleship Number 2" two days earlier so her name could be reused for the dreadnought battleship Massachusetts (BB-54).[16]

She was struck from the Naval Vessel Register on 22 November 1920 and loaned to the United States Department of War, then used as a target ship for experimental artillery. She was scuttled in shallow water in the Gulf of Mexico off Pensacola on 6 January 1921 and bombarded by the coastal batteries of Fort Pickens and by railway artillery. On 20 February 1925, the Department of War returned her wreck to the U.S. Navy, which offered her for scrap, but no acceptable bids were received.[16] Another attempt to sell her for scrap her was made in 1956, but the State of Florida prevented this. Eventually the ship was declared the property of the State of Florida by the Supreme Court of Florida. On 10 June 1993—the centennial anniversary of her launching—the site became the fourth Florida Underwater Archaeological Preserve. In 2001 the wreck also was added to the National Register of Historic Places, and it still serves as an artificial reef and diving spot.[39] Massachusetts′s figurehead is on display in Dahlgren Hall at the United States Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland.

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ Experimental data for BB-1 and BB-2 was lumped together and the rounded average calculated. See Bryan 1901.

- ↑ Sources conflict on this. Reilly & Scheina 1980 claim first that Massachusetts had five tubes, but give three in their data table. DANFS says six tubes, while Friedman 1985 states the contract called for seven tubes, but Massachusetts was completed with five.

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Reilly & Scheina 1980, p. 68.

- 1 2 Friedman 1985, p. 425.

- ↑ Reilly & Scheina 1980, p. 58.

- ↑ Bryan 1901.

- ↑ Reilly & Scheina 1980, p. 63.

- ↑ National Register Information System.

- ↑ Reilly & Scheina 1980, p. 67.

- ↑ Friedman 1985, pp. 24–25.

- ↑ Gardiner & Lambert 1992, p. 121.

- ↑ Chesneau, Koleśnik & Campbell 1979, p. 140.

- ↑ The New York Times & 1 December 1890.

- 1 2 Reilly & Scheina 1980, p. 69.

- 1 2 The New York Times & 12 March 1896.

- ↑ The New York Times & 10 June 1893.

- ↑ The New York Times & 26 April 1896.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 DANFS Massachusetts (BB-2).

- ↑ Graham & Schley 1902, p. 93–94.

- ↑ Graham & Schley 1902, pp. 116, 120.

- ↑ Graham & Schley 1902, pp. 141–162.

- ↑ Graham & Schley 1902, pp. 164–167.

- ↑ DANFS Indiana (BB-1).

- ↑ Graham & Schley 1902, p. 203.

- ↑ Graham & Schley 1902, pp. 299–300.

- ↑ The New York Times & 26 July 1898.

- ↑ Graham & Schley 1902, pp. 471–472.

- ↑ The New York Times & 11 December 1898.

- ↑ The New York Times & 1 April 1899.

- ↑ The New York Times & 14 April 1900.

- ↑ The New York Times & 6 June 1900.

- ↑ The New York Times & 25 March 1901.

- ↑ The New York Times & 23 March 1901.

- ↑ Reilly & Scheina 1980, p. 56.

- ↑ The New York Times & 23 August 1903.

- ↑ The New York Times & 15 December 1904.

- ↑ The New York Times & 8 January 1906.

- ↑ Reilly & Scheina 1980, p. 62.

- ↑ The New York Times & 1 December 1911.

- ↑ The New York Times & 4 February 1912.

- ↑ Museums in the Sea.

References

Print references

- Chesneau, Roger; Koleśnik, Eugène M.; Campbell, N.J.M. (1979). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships, 1860–1905. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-133-5.

- Friedman, Norman (1985). U.S. Battleships, An Illustrated Design History. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-715-1.

- Gardiner, Robert; Lambert, Andrew D. (1992). Steam, Steel & Shellfire: The Steam Warship 1815–1905. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-564-0.

- Graham, George E.; Schley, Winfield S. (1902). Schley and Santiago: An Historical Account of the Blockade and Final Destruction of the Spanish Fleet Under Command of Admiral Pasquale Cervera, July 3, 1898. Texas: W.B. Conkey Company. OCLC 1866852.

- Reilly, John C.; Scheina, Robert L. (1980). American Battleships 1886–1923: Predreadnought Design and Construction. London: Arms and Armour Press. ISBN 0-85368-446-4.

Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships

- "Indiana". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History and Heritage Command. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- "Massachusetts". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History & Heritage Command. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

The New York Times

- "The new American navy; Secretary Tracy reports in favor of progress" (PDF). The New York Times. 1 December 1890. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- "Another powerful war vessel; builders trial of the Massachusetts tuesday" (PDF). The New York Times. New York City. 12 March 1896. Retrieved 23 June 2010.

- "New battle ship launched; the Massachusetts floated in the broad Delaware" (PDF). The New York Times. New York City. 10 June 1893. Retrieved 4 June 2010.

- "The best in the world; record breaking trial of the battleship Massachusetts" (PDF). The New York Times. New York City. 26 April 1896. Retrieved 23 June 2010.

- "Sampson's story of the battle; official report of the destruction of Cervera's squadron" (PDF). The New York Times. 26 July 1898. Retrieved 18 May 2010.

- "The Massachusetts hurt; battleships strikes a sunken obstruction off Governors Island" (PDF). The New York Times. New York City. 11 December 1898. Retrieved 20 July 2010.

- "Massachusetts leaves dock" (PDF). The New York Times. New York City. 1 April 1899. Retrieved 20 July 2010.

- "Navy short of officers; there are not enough to keep warships in commission" (PDF). The New York Times. 14 April 1900. Retrieved 18 May 2010.

- "Hurry order to the navy; department wants to find Out what can Be done in an emergency" (PDF). The New York Times. 6 June 1900. Retrieved 21 July 2010.

- "Why the Massachusetts grounded" (PDF). The New York Times. 25 March 1901. Retrieved 18 May 2010.

- "Movements of naval vessels" (PDF). The New York Times. 23 March 1901. Retrieved 21 July 2010.

- "The Massachusetts in port; battleship recently injured on a rock" (PDF). The New York Times. 23 August 1903. Retrieved 21 July 2010.

- "Three killed on battleship" (PDF). The New York Times. 15 December 1904. Retrieved 21 July 2010.

- "Reconstructed Indiana ready" (PDF). The New York Times. 8 January 1906. Retrieved 19 May 2010.

- "Meyer wants navy ever ready for war" (PDF). The New York Times. 1 December 1911. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- "Admiral Knights's command" (PDF). The New York Times. 4 February 1912. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

Other

- Bryan, B. C. (1901). "The Steaming Radius of United States Naval Vessels". Journal of the American Society for Naval Engineers. 13 (1): 50–69. doi:10.1111/j.1559-3584.1901.tb03372.x. (subscription required)

- National Park Service (2010-07-09). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- "USS Massachusetts learn about the history audio transcript" (PDF). Florida's "Museums in the Sea". Retrieved 23 July 2010.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to USS Massachusetts (BB-2). |

- Photo gallery of Massachusetts at NavSource Naval History

- MaritimeQuest USS Massachusetts BB-2 Photo Gallery

- Museums in the Sea USS Massachusetts

_sinking_1921.jpg)