List of portrait drawings by Hans Holbein the Younger

The following is a list of portrait drawings by Hans Holbein the Younger that are generally accepted as by his own hand.

Royal Collection

| Work. | Title. | Date. | Medium | Size | Notes | Related works |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

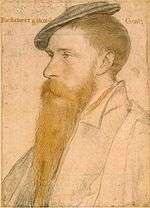

|

Simon George[1] | c. 1535 | Black and coloured chalks, pen and ink, brush and ink, also metalpoint on pale pink prepared paper. | 27.9 × 19.1 cm | Simon George of Cornwall was an English nobleman.[2]

The drawing is related to a circular painting by Holbein in the Städel Museum, Frankfurt.[2] As was revealed by X-ray radiograms, the sitter's beard in the painting was initially much shorter, making it more similar to the drawing.[3][4] |

|

|

William Reskimer[5] | c. 1532 – c. 1534 | Black and coloured chalks, pen and ink, and metalpoint on pale pink prepared paper. | 29.0 × 21.0 cm | William Reskimer held a number of minor positions at Henry VIII's court.[5]

The drawing is a study for a painted portrait by Holbein, also in the Royal Collection.[6] |

|

|

An unidentified woman[7] | c. 1532 – c. 1543 | Black and coloured chalks, white bodycolour, and pen with black and brown ink on pale pink prepared paper which has been trimmed to outlines and pasted onto another sheet. | 27.1 × 16.9 cm | Formerly identified as Amalia of Cleves, sister of Anne of Cleves, the fourth wife of Henry VIII.[8] | |

|

Elizabeth Audley[9] | c. 1538 | Black and coloured chalks, pen and ink, and metalpoint on pale pink prepared paper. | 29.3 × 20.8 cm | Elizabeth, Lady Audley was the second wife of Thomas Audley, 1st Baron Audley of Walden and daughter of Thomas Grey, 2nd Marquess of Dorset.[9]

The drawing relates to a circular miniature by Holbein, also in the Royal Collection.[10] |

|

|

Anne Boleyn[14] | c. 1533 – c. 1536 | Black and coloured chalks on pale pink prepared paper. | 28.2 × 19.3 cm | Traditionally believed to be Anne Boleyn, the second wife of Henry VIII and mother of Elizabeth I.[14] The drawing is consistent with both the only undisputed contemporary depiction of Anne — the badly worn 1534 coronation medal in the British Museum[15] — and an anonymous French description of her being "scrofulous and therefore fastening her dress very high on the throat, in the fashion employed by the goitrous people".[16]

Another drawing by Holbein, formerly identified as that of Anne Boleyn, is in the British Museum, London.[17] |

|

|

James Butler[18] | c. 1537 | Black and coloured chalks, white bodycolour, red, blue-grey, and brown wash, pen and ink, and brush and ink on pale pink prepared paper. | 40.1 × 29.2 cm | The sitter is James Butler, 9th Earl of Ormond and 2nd Earl of Ossory.[18]

Formerly identified as his cousin Thomas Boleyn, 1st Earl of Wiltshire (father of Anne Boleyn, the second wife of Henry VIII).[19] |

|

|

Alice London, Lady Borough[20][21] | c. 1541 | Black and coloured chalks on pale pink prepared paper. | 27.2 × 19.6 cm | Recently thought by some to be Catherine Parr. Catherine’s first father-in-law, Lord Thomas Burgh, had to pull his connections just to get his wife, Lady Borough, painted by Holbein.[22] Burgh married twice; first in 1496 to Agnes (died 1522), daughter of Sir William Trywhitt of Kettleby. Sometime after 15 March 1538, Burgh married secondly to the widowed Lady Alice Bedingfield of Oxburgh, daughter of William London. By 1541, Lord Burgh was part of the household of Prince Edward. The portrait was done some time during the couples stay at court; 1540-42.[20] | |

|

Nicholas Bourbon[23] | 1535 | Black and coloured chalks, and pen and ink on pale pink prepared paper. | 30.8 × 25.9 cm | Nicholas Bourbon was a French poet at the court of Henry VIII.[23] He was a friend of Holbein and described him in a letter as "the royal painter, the Apelles of our time".[24] He also wrote verses for an edition of Holbein's Historiarum veteris instrumenti icones ad vivum expressae.[25]

The drawing is a study for a painted portrait by Holbein, now lost, but possibly recorded in a 1535 woodcut.[25] |

|

|

George Brooke[26] | c. 1532 – c. 1543 | Black and coloured chalks, pen and ink and metalpoint, on pale pink prepared paper. | 28.9 × 20.3 cm | The sitter is George Brooke, 9th Baron Cobham.[26]

A painting by a follower of Holbein, tentatively dated to the 1540s, closely following the drawing, formerly in a German private collection, was sold at auction in 2011.[27] |

|

|

Margaret Butts[28] | c. 1541 – c. 1543 | Black and coloured chalks, pen and ink, brush and ink, and metalpoint on pale pink prepared paper. | 37.7 × 27.2 cm | Margaret, Lady Butts was a lady-in-waiting to Princess Mary and belonged to the circle of Catherine Parr, the sixth wife of Henry VIII.[28]

The drawing is a study for a portrait by Holbein in the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston.[29] |

|

|

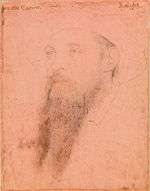

Gavin Carew[32] | c. 1532 – c. 1543 | Black and coloured chalks, pen and ink, and metalpoint on pale pink prepared paper. | 27.2 × 21.3 cm | The sitter is Sir Gavin Carew.[32]

A drawing of his nephew[33][34] Admiral Sir George Carew, by Holbein, is also in the Royal Collection; a related circular painting by Holbein is in Weston Park, owned by the Earls of Bradford.[35] A drawing of his kinsman[34] Nicholas Carew, by Holbein, is in the Kunstmuseum Basel in Basel, Switzerland;[36] a related painting by Holbein is in the Drumlanrig Castle, part of the Buccleuch collection.[37] |

|

|

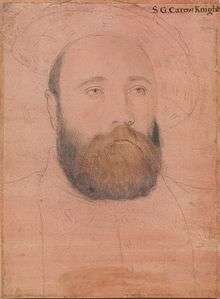

George Carew[35] | c. 1532 – c. 1543 | Black and coloured chalks, and metalpoint on pale pink prepared paper. | 31.6 × 23.3 cm | Admiral Sir George Carew was the commander of the Royal Navy flagship Mary Rose when it sank in 1545.[35]

The drawing is related to a circular painting by Holbein in Weston Park, owned by the Earls of Bradford.[35] |

|

|

Edward Fiennes de Clinton[42] | c. 1532 – c. 1543 | Black and coloured chalks on pale pink prepared paper. | 22.0 × 14.5 cm | The sitter is Edward Clinton, 1st Earl of Lincoln.[42] | |

|

John Colet[43] | c. 1535 | Black and coloured chalks, pen and ink, brush and ink, and metalpoint on pale pink prepared paper. | 26.8 × 20.5 cm | John Colet was the Dean of St Paul's Cathedral and the founder of St Paul's School, London. He died in 1519, years before Holbein's first visit to England.[43]

The drawing is a study of a lost bust of circa 1520 attributed to Pietro Torrigiano and probably based on a death mask.[44] A 16th-century cast,[45] preserved in St Paul's School since at least 1552,[46] is now at the Mercers' Hall, London[47] (a copy of the cast is in the National Portrait Gallery).[48] The cast is actually a composite, only the head being original and the rest probably dating to the late 18th century and based on Holbein's drawing.[49] The head was found among the ruins of the school after the 1666 Great Fire of London by antiquarian John Bagford.[50] The very same fire also destroyed the original bust, which formed a part of Colet's tomb in the Old St Paul's Cathedral.[51] The tomb's appearance is recorded in an engraving of 1656, possibly by Wenceslaus Hollar,[52] and a watercolour miniature of circa 1585, probably by William Segar, on the cover of the manuscript Statu[t]es of Saint Paul's School, preserved at the Mercers' Hall;[53][47] the badly damaged remains of the bust, comprising only torso and hands, were reproduced in an 1809 engraving,[54] but have since disappeared.[55] |

|

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg) |

Anne Cresacre[56] | c. 1527 | Black and coloured chalks. | 37.2 × 26.6 cm | Anne Cresacre, aged 15, was the ward of Thomas More, later the wife of his son John More the Younger.[56][57]

The drawing is one of the eight individual portrait studies for a group portrait of Thomas More's family preserved in the Royal Collection.[58] Destroyed by fire at the Kremsier Castle (Czech Republic) in 1752,[59][60] its appearance is preserved in an annotated drawing by Holbein, now in Kunstmuseum Basel.[61][58] There are also several later copies, including three 1592–1594 versions by Rowland Lockey: a watercolor miniature in the Victoria and Albert Museum[62] and two oils on canvas, one in the National Portrait Gallery,[63] and one at the Nostell Priory, West Yorkshire.[64] |

|

|

Elizabeth Dauncey[66] | c. 1526 – c. 1527 | Black and coloured chalks. | 36.7 × 26.0 cm | Elizabeth Dauncey, aged 21, was the daughter of Thomas More.[57][66] In 1525, she married William Dauncey, son of Sir John Dauncey, Privy Councillor and Knight of the Body to Henry VIII.[57]

The drawing is one of the eight individual portrait studies for a group portrait of Thomas More's family preserved in the Royal Collection.[58] Destroyed by fire at the Kremsier Castle (Czech Republic) in 1752,[59][60] its appearance is preserved in an annotated drawing by Holbein, now in Kunstmuseum Basel.[61][58] There are also several later copies, including three 1592–1594 versions by Rowland Lockey: a watercolor miniature in the Victoria and Albert Museum[62] and two oils on canvas, one in the National Portrait Gallery,[63] and one at the Nostell Priory, West Yorkshire.[64] |

|

|

Margaret, Marchioness of Dorset[11] | c. 1532 – c. 1535 | Black and coloured chalks, pen and ink, and metalpoint on pale pink prepared paper. | 33.2 × 23.6 cm | The sitter is Margaret Wotton, Marchioness of Dorset.[11] In 1533, she was one of the two godmothers to the future Queen Elizabeth I of England.[72] Her husband was Thomas Grey, 2nd Marquess of Dorset, a prominent courtier at the court of Henry VIII, key witness in favour of the King's divorce of Catherine of Aragon.[73] One of their many grandchildren was Lady Jane Grey, the Nine Day Queen.[72]

The drawing is a study for a painted portrait, now lost; a 1560s copy is in the Weiss Gallery in London;[12] a late-16th-century one is at Anglesey Abbey, Lode, Cambridgeshire.[13] |

_-_Margaret%2C_Marchioness_of_Dorset_(Anglesey_Abbey).jpg) |

|

Edward, Prince of Wales[74] | 1538 | Black and coloured chalks, and pen and ink on pale pink prepared paper. | 26.4 × 22.4 cm | The sitter is the future King Edward VI, son of Henry VIII and Jane Seymour, aged 1.[74]

The drawing is a study for a painting by Holbein in the National Gallery of Art, Washington.[75] Holbein gave the painting to the King as the 1539 New Year's gift.[74][75] |

|

|

Edward, Prince of Wales[76] | c. 1540 – c. 1543 | Black and coloured chalks, and pen and ink on pale pink prepared paper. | 27.3 × 22.7 cm | The sitter is the future King Edward VI, son of Henry VIII and Jane Seymour, aged 3–5.[76]

Another drawing of Edward, aged 1, by Holbein, is also in the Royal Collection;[74] a related painting by Holbein is in the National Gallery of Art, Washington.[75] |

|

|

Margaret Elyot[77] | c. 1532 – c. 1534 | Black and coloured chalks, white bodycolour, and pen and ink on pale pink prepared paper. | 27.8 × 20.8 cm | Margaret à Barrow, Lady Elyot was the wife of the English diplomat and scholar Sir Thomas Elyot.[77]

A drawing of her husband, by Holbein, is also in the Royal Collection.[78] |

|

|

Thomas Elyot[78] | c. 1532 – c. 1534 | Black and coloured chalks, white bodycolour, and brush and ink on pale pink prepared paper. | 27.8 × 20.8 cm | Sir Thomas Elyot was an English diplomat and scholar.[78] His best-known work is The Boke Named the Governour, a humanist book of political instruction dedicated to Henry VIII.[79] He served as an ambassador to Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor.[78]

A drawing of his wife Margaret à Barrow, Lady Elyot, by Holbein, is also in the Royal Collection.[77] |

|

|

John Fisher[80] | c. 1532 – c. 1534 | Black and coloured chalks, brown wash, pen and ink, brush and ink on pale pink prepared paper. | 38.2 × 23.2 cm | John Fisher, the Bishop of Rochester and Chancellor of the University of Cambridge, was beheaded on the order of Henry VIII for refusing to accept the King as Supreme Head of the Church of England; he is now recognized as Saint by both the Catholic Church and the Church of England.[81][82]

An early copy, oil-on-paper face pattern of circa 1527, is preserved in the National Portrait Gallery, London.[83] A 17th-century copy, drawing sometimes attributed to Peter Paul Rubens, is in the British Museum.[84][85][86] |

|

|

William Fitzwilliam[87] | c. 1536 – c. 1540 | Black and coloured chalks, and metalpoint on pale pink prepared paper. | 38.3 x 27.0 cm | William FitzWilliam, 1st Earl of Southampton was a part of Henry VIII's inner circle since before accession.[87] He went on to serve as the Ambassador to France, Treasurer of the Household, Lord High Admiral, and Lord Privy Seal.[88]

The drawing is a study for a painting by Holbein, now lost (either the original or a copy perished in the fire that destroyed Cowdray House, Sussex, in 1793);[89][85] one copy survives in the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge.[90] |

_-_William_Fitzwilliam%2C_Earl_of_Southampton_(Fitzwilliam_Museum).jpg) |

|

John Gage[91] | c. 1532 – c. 1543 | Black and coloured chalks, pen and ink, and metalpoint on pale pink prepared paper. | 39.4 × 29.0 cm | John Gage was an English courtier at the courts of Henry VIII, Edward VI, and Mary I.[92][93] | |

|

Margaret Giggs[94] | c. 1526 – c. 1527 | Black and coloured chalks. | 38.5 × 27.3 cm | Margaret Clement (née Giggs), aged 19, was the foster daughter of Thomas More.[94][95] In 1526, she married John Clement, tutor to the More children and future President of the Royal College of Physicians.[95]

The drawing is one of the eight individual portrait studies for a group portrait of Thomas More's family preserved in the Royal Collection.[58] Destroyed by fire at the Kremsier Castle (Czech Republic) in 1752,[59][60] its appearance is preserved in an annotated drawing by Holbein, now in Kunstmuseum Basel.[61][58] There are also several later copies, including three 1592–1594 versions by Rowland Lockey: a watercolor miniature in the Victoria and Albert Museum[62] and two oils on canvas, one in the National Portrait Gallery,[63] and one at the Nostell Priory, West Yorkshire.[64] |

|

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg) |

John Godsalve[96] | c. 1532 – c. 1534 | Black and red chalks, pen and ink, brush and ink, bodycolour, white heightening, on pale pink prepared paper. | 36.2 × 29.2 cm | Sir John Godsalve was an English politician.[96]

A 16th-century painting by an imitator of Holbein, sometimes thought to be based on this drawing, is in the Philadelphia Museum of Art.[96][97] |

|

_by_Hans_Holbein_the_Younger.jpg) |

Henry Guildford[102] | 1527 | Black and coloured chalks, and pen and ink. | 38.3 × 29.4 cm | Sir Henry Guildford was one of Henry VIII’s closest friends.[102] At different times, he held the positions of an Esquire of the Body, Master of the Revels, Master of the Horse and Comptroller of the Royal Household.[103]

The drawing is a study for a painted portrait by Holbein, also in the Royal Collection.[104] |

_-_Sir_Henry_Guildford.jpg) |

|

Cicely Heron[60] | c. 1526 – c. 1527 | Black and coloured chalks. | 37.8 × 28.1 cm | Cicely Heron, aged 20, was the daughter of Thomas More.[60][105] In 1525, she married Giles Heron, a ward of More.[105]

The drawing is one of the eight individual portrait studies for a group portrait of Thomas More's family preserved in the Royal Collection.[58] Destroyed by fire at the Kremsier Castle (Czech Republic) in 1752,[59][60] its appearance is preserved in an annotated drawing by Holbein, now in Kunstmuseum Basel.[61][58] There are also several later copies, including three 1592–1594 versions by Rowland Lockey: a watercolor miniature in the Victoria and Albert Museum[62] and two oils on canvas, one in the National Portrait Gallery,[63] and one at the Nostell Priory, West Yorkshire.[64] |

|

|

Mary Heveningham[106] | c. 1532 – c. 1543 | Black and coloured chalks, white bodycolour, pen and ink, and brush and ink on pale pink prepared paper. | 30.3 × 21.1 cm | Mary, Lady Heveningham was the first cousin of Anne Boleyn, the second wife of Henry VIII.[106][107] The main editor of and a major contributor to the famous compilation of poetry known as Devonshire Manuscript, she was romantically linked with poets Thomas Clere, Thomas Wyatt, and Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey; she may also have been a mistress of Henry VIII.[107] A painting by Holbein, formerly thought to be of Mary, is at the Oskar Reinhart Collection, Winterthur.[99][101][108] |

|

|

Elizabeth Hoby[109] | c. 1532 – c. 1543 | Black and coloured chalks, pen and ink, and brush and ink on pale pink prepared paper. | 27.5 × 20.1 cm | Elizabeth, Lady Hoby was a member of Queen Catherine Parr's circle.[109] She was the daughter of Sir Walter Stonor, the Lieutenant of the Tower of London, and the wife of Sir Philip Hoby, the ambassador to the Holy Roman Empire and Flanders.[110][111]

A drawing of her husband, by Holbein, is also in the Royal Collection.[112] |

|

|

Philip Hoby[112] | c. 1532 – c. 1543 | Black and coloured chalks, and grey bodycolour on pale pink prepared paper. | 30.1 × 22.3 cm | Sir Philip Hoby was the ambassador to the Holy Roman Empire and Flanders; he and Holbein travelled together on missions to find Henry VIII a fourth wife.[111]

A drawing of his wife Elizabeth, Lady Hoby, by Holbein, is also in the Royal Collection.[109] |

|

|

An unidentified woman[113] | c. 1532 – c. 1543 | Black and coloured chalks, and metalpoint on pale pink prepared paper. | 27.7 × 19.7 cm | Formerly identified as Catherine Howard, the fifth wife of Henry VIII.[114] As such, it was associated with two circular miniatures by Holbein, also formerly thought to be of Howard, one in the Royal collection[115] and one in the Strawberry Hill House, part of the Buccleuch collection;[116] an additional painting by Holbein, also formerly thought to be of Howard, is at the Toledo Museum of Art in Toledo, Ohio.[117] | |

|

Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey[118] | c. 1533 – c. 1536 | Black and coloured chalks, and pen and ink on pale pink prepared paper. | 29.0 × 21.0 cm | Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey was an English aristocrat, and one of the founders of English Renaissance poetry, introducing blank verse into the English language in his translation of Virgil’s Aeneid.[118] He was also a childhood friend of Henry VIII's illegitimate son Henry Fitzroy.[119]

The Royal Collection has two more drawings of Henry Howard, one by Holbein[119] and one by a follower.[120] A painted portrait of Henry Howard, by Holbein, is in the São Paulo Museum of Art, Brazil.[121] |

|

_by_Hans_Holbein_the_Younger.jpg) |

Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey[119] | c. 1532 – c. 1533 | Black and coloured chalks, and pen and ink on pale pink prepared paper. | 25.1 × 20.5 cm | Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey was an English aristocrat, and one of the founders of English Renaissance poetry, introducing blank verse into the English language in his translation of Virgil’s Aeneid.[118] He was also a childhood friend of Henry VIII's illegitimate son Henry Fitzroy.[119]

The Royal Collection has two more drawings of Henry Howard, one by Holbein[118] and one by a follower.[120] A painted portrait of Henry Howard, by Holbein, is in the São Paulo Museum of Art, Brazil.[121] |

|

|

Frances, Countess of Surrey[123] | c. 1532 – c. 1533 | Black, white and coloured chalks, white bodycolour, and pen and ink, on pale pink prepared paper. | 31.0 × 21.0 cm | Frances Howard, Countess of Surrey was the daughter of John de Vere, 15th Earl of Oxford and the wife of Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey.[123]

The Royal Collection has three drawings of her husband, two by Holbein, one in three-quarters and one frontal, and another one by a follower;[118][119][120] an additional painting, by Holbein, is in the São Paulo Museum of Art, Brazil.[121] |

|

|

Mary, Duchess of Richmond and Somerset[124] | c. 1532 – c. 1533 | Black and coloured chalks, and brush and ink on pale pink prepared paper. | 26.6 × 19.9 cm | Mary FitzRoy, Duchess of Richmond and Somerset was the wife of Henry VIII's only acknowledged illegitimate son Henry FitzRoy, 1st Duke of Richmond and Somerset.

A portrait painting of her father Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk, by Holbein, is also in the Royal Collection.[122] The Royal Collection also has three drawings of her brother Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey, two by Holbein, one in three-quarters and one frontal, and another one by a follower;[118][119][120] an additional painting, by Holbein, is in the São Paulo Museum of Art, Brazil.[121] |

|

|

Lady Lister[125] | c. 1532 – c. 1543 | Black and coloured chalks, pen and ink and brush and ink on pale pink prepared paper. | 29.0 × 21.0 cm | The precise identity of the sitter is unknown.[125] One suggestion is Lady Jane Lister, the wife of Sir Richard Lyster, Lord Chief Justice.[126] | |

|

Princess Mary[127] | c. 1536 | Black and coloured chalks, and pen and ink on pale pink prepared paper. | 38.6 × 29.1 cm | The sitter is traditionally identified as the future Queen Mary I.[127] | |

|

An unidentified man[128] | c. 1532 – c. 1543 | Black and coloured chalks, and pen and ink on pale pink prepared paper. | 28.5 × 23.3 cm | Formerly identified as the theologian Philipp Melanchthon, one of the founders of Lutheranism.[128] A portrait miniature of Melanchton, by Holbein, is in the Lower Saxony State Museum in Hanover, Germany; it is unlikely Holbein ever met him, so the miniature is probably based on pictures by other artists, like those by Lucas Cranach the Elder or Albrecht Dürer.[129] | |

|

Joan Meutas[130] | c. 1536 – c. 1543 | Black and coloured chalks on pale pink prepared paper. | 28.1 × 21.0 cm | The sitter is Lady Joan Meutas[130] She was a lady of the privy chamber of Queen Jane Seymour, Henry VIII's third wife. In 1537, she married courtier and diplomat Peter Meutas.[131]

Lady Meutas's oval medallion is similar to a design for a Penitent Mary Magdalene medallion in the Kunstmuseum Basel in Basel, Switzerland.[132][133] |

|

|

Mary Monteagle[134] | c. 1538 – c. 1540 | Black and coloured chalks, pen and ink, and brush and ink on pink prepared paper. | 29.7 × 20.0 cm | Lady Mary Brandon, Baroness Monteagle was a lady-in-waiting to Jane Seymour, third wife of Henry VIII.[135] She was the daughter of Charles Brandon, 1st Duke of Suffolk and wife of Thomas Stanley, 2nd Lord Monteagle.[134]

She was formerly identified as the sitter for two portrait miniatures by Holbein, one in the Royal collection[115] and one in the Strawberry Hill House, part of the Buccleuch collection.[116] |

|

|

John More[67] | c. 1526 – c. 1527 | Black and coloured chalks. | 35.1 × 27.3 cm | Sir John More, aged 76, was the father of Thomas More.[57][67] He was a lawyer and a judge.[57][136]

The drawing is one of the eight individual portrait studies for a group portrait of Thomas More's family preserved in the Royal Collection.[58] Destroyed by fire at the Kremsier Castle (Czech Republic) in 1752,[59][60] its appearance is preserved in an annotated drawing by Holbein, now in Kunstmuseum Basel.[61][58] There are also several later copies, including three 1592–1594 versions by Rowland Lockey: a watercolor miniature in the Victoria and Albert Museum[62] and two oils on canvas, one in the National Portrait Gallery,[63] and one at the Nostell Priory, West Yorkshire.[64] |

|

|

John More[65] | c. 1526 – c. 1527 | Black and coloured chalks. | 38.1 × 28.1 cm | John More, aged 19, was the son of Thomas More.[65][105]

The drawing is one of the eight individual portrait studies for a group portrait of Thomas More's family preserved in the Royal Collection.[58] Destroyed by fire at the Kremsier Castle (Czech Republic) in 1752,[59][60] its appearance is preserved in an annotated drawing by Holbein, now in Kunstmuseum Basel.[61][58] There are also several later copies, including three 1592–1594 versions by Rowland Lockey: a watercolor miniature in the Victoria and Albert Museum[62] and two oils on canvas, one in the National Portrait Gallery,[63] and one at the Nostell Priory, West Yorkshire.[64] |

|

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg) |

Thomas More[68] | c. 1526 – c. 1527 | Black and coloured chalks, the outlines pricked for transfer. | 39.8 × 29.9 cm | The sitter is Sir Thomas More.[68]

This drawing is a study for a painted portrait by Holbein in the Frick Collection, New York.[70] Another drawing similar to this one is also in the Royal Collection.[69] The painting and the drawings relate to a group portrait of Thomas More's family.[58] Destroyed by fire at the Kremsier Castle (Czech Republic) in 1752,[59][60] its appearance is preserved in an annotated drawing by Holbein, now in Kunstmuseum Basel.[61][58] There are also several later copies, including three 1592–1594 versions by Rowland Lockey: a watercolor miniature in the Victoria and Albert Museum[62] and two oils on canvas, one in the National Portrait Gallery,[63] and one at the Nostell Priory, West Yorkshire.[64] |

|

_by_Hans_Holbein_the_Younger.jpg) |

Thomas More[69] | c. 1526 – c. 1527 | Black and coloured chalks, and brown wash. | 37.6 × 25.5 cm | The sitter is Sir Thomas More.[69]

This drawing is very similar to another one, also in the Royal Collection, which is thought to be a study for a painted portrait by Holbein in the Frick Collection, New York.[70] The painting and the drawings relate to a group portrait of Thomas More's family.[58] Destroyed by fire at the Kremsier Castle (Czech Republic) in 1752,[59][60] its appearance is preserved in an annotated drawing by Holbein, now in Kunstmuseum Basel.[61][58] There are also several later copies, including three 1592–1594 versions by Rowland Lockey: a watercolor miniature in the Victoria and Albert Museum[62] and two oils on canvas, one in the National Portrait Gallery,[63] and one at the Nostell Priory, West Yorkshire.[64] |

|

|

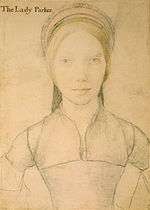

Grace Parker[140] | c. 1540 – c. 1543 | Black and coloured chalks on pale pink prepared paper. | 29.8 x 20.8 cm | The sitter is probably Lady Grace Parker, the wife of the politician Sir Henry Parker.[140]

Formerly identified as Jane Parker, sister-in-law to Anne Boleyn, Henry VIII's second wife.[141] |

|

|

William Parr[142] | c. 1538 – c. 1542 | Black and coloured chalks, white bodycolour, pen and ink, and brush and ink on pale pink prepared paper. | 31.7 × 21.2 cm | William Parr, 1st Marquess of Northampton was the brother of Catherine Parr, the sixth wife of Henry VIII.[142][143]

A drawing sometimes identified as of his sister Anne Herbert, Countess of Pembroke,[144] by Holbein, is also in the Royal Collection.[145] |

|

|

Thomas Parry[146] | c. 1532 – c. 1543 | Black and coloured chalks, and pen and ink on pale pink prepared paper. | 25.1 × 18.5 cm | Sir Thomas Parry was an English courtier who went on to become the Comptroller of the Household to Elizabeth I.[146][147] | |

|

John Poyntz[148] | c. 1532 – c. 1543 | Black and coloured chalks, pen and ink, and brush and ink on pale pink prepared paper. | 29.5 × 23.3 cm | John Poyntz was an English courtier and politician.[148][149]

A similar drawing, attributed to Holbein, is in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.[150] A drawing of his nephew[149] Nicholas Poyntz, by Holbein, is also in the Royal Collection.[151] |

|

|

Nicholas Poyntz[151] | c. 1533 – c. 1543 | Black and coloured chalks, and pen and ink on pale pink prepared paper. | 28.4 × 18.3 cm | The sitter is Sir Nicholas Poyntz.[151] He was a prominent courtier during the later part of Henry VIII's reign and commanded the warship the Great Galley during the war of the Rough Wooing.[152]

This drawing is a study for a painted portrait, now lost; several 16th-century copies survive, including a reduced version in the National Portrait Gallery, London,[153] and a full one at the Sandon Hall, Staffordshire, owned by the Earls of Harrowby;[154] a 17th-century copy is at Ickworth House near Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk.[155] |

_-_Nicholas_Poyntz_(Earl_of_Harrowby).jpg) |

|

Lady Ratcliffe[158] | c. 1532 – c. 1543 | Black and coloured chalks, pen and ink, brush and ink, and metalpoint on pale pink prepared paper. | 30.1 × 20.3 cm | The precise identity of the sitter is unknown.[158] Robert Radcliffe, 1st Earl of Sussex had three wives, the third one, prominent courtier Mary Arundell being the most likely candidate.[159] The wife of the Earl's third son Sir Humphrey Radcliffe has also been suggested.[158] | |

|

Elizabeth Rich[160] | c. 1532 – c. 1543 | Black and coloured chalks, pen and ink, and metalpoint on pale pink prepared paper. | 37.4 × 30.3 cm | Elizabeth, Lady Rich was the wife of Richard Rich, 1st Baron Rich.[160]

A related painted portrait by the workshop of Holbein is in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.[161] |

|

|

Richard Rich[162] | c. 1532 – c. 1543 | Black and coloured chalks, and pen and ink on pale pink prepared paper. | 32.2 × 26.2 cm | The sitter is Richard Rich, 1st Baron Rich.[162] A prominent court official, he eventually rose to become the Lord Chancellor during the reign of Edward VI.[163]

The drawing is a study for a painted portrait, now lost; the last known copy was destroyed by fire at Knepp Castle in West Grinstead, Sussex, in 1904.[3][164] |

|

|

Francis Russell[165] | c. 1534 – c. 1538 | Black and coloured chalks, and pen and ink on pale pink prepared paper. | 23.9 × 17.9 cm | The sitter is Francis Russell, 2nd Earl of Bedford.[165]

A drawing of his father, John Russell, 1st Earl of Bedford, by Holbein, is also in the Royal Collection.[166] |

|

|

John Russell[166] | c. 1532 – c. 1543 | Black and coloured chalks, and white bodycolour on pale pink prepared paper. | 34.9 × 29.2 cm | John Russell, 1st Earl of Bedford was an important court official, serving as Lord High Admiral and later Lord Privy Seal; in 1520, he was present at the embassy of the Field of the Cloth of Gold and lost an eye during the Siege of Morlaix of 1522.[166][167]

A drawing of his son, Francis Russell, 2nd Earl of Bedford, by Holbein, is also in the Royal Collection.[165] |

|

|

Jane Seymour[168] | c. 1536 – c. 1537 | Black and coloured chalks, pen and ink, and metalpoint, on pale pink prepared paper. | 50.0 × 28.5 cm | Jane Seymour was the third wife of Henry VIII and the mother of Edward VI.[168]

The drawing is a study for a painted portrait by Holbein in the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria;[169] a workshop copy, sometimes attributed to Holbein himself, is in the Mauritshuis, The Hague.[170] The portrait also matches the description of Jane in the so-called Whitehall Mural, the now lost Holbein's wall-painting of the Tudor dynasty in the Privy chamber of the Palace of Whitehall; destroyed by fire in 1698, its appearance is recorded in an oil-on-canvas copy by Remigius van Leemput in the Royal Collection.[171] |

|

|

William Sharington[172] | c. 1532 – c. 1543 | Black and coloured chalks, and brush and ink on pale pink prepared paper. | 30.1 × 20.3 cm | Sir William Sharington was an English courtier, best remembered for his involvement in the Bristol Mint embezzlement scandal.[173] | |

|

Richard Southwell[174] | 1536 | Black and coloured chalks, pen and ink, and metalpoint on pale pink prepared paper. | 36.6 × 27.7 cm | Sir Richard Southwell was an English courtier and politician.[174] The drawing is a study for a painted portrait by Holbein in Uffizi, Florence.[175] |

|

|

Edward Stanley[176] | c. 1532 – c. 1543 | Black and coloured chalks, pen and ink, and brush and ink on pale pink prepared paper. | 28.1 × 19.7 cm | The sitter is Edward Stanley, 3rd Earl of Derby, cup-bearer to Anne Boleyn.[176][177] | |

|

Thomas Lestrange[178] | c. 1536 | Black and coloured chalks, pen and ink, and metalpoint, on pale pink prepared paper. | 24.3 × 21.0 cm | The sitter is Sir Thomas Lestrange, a minor courtier and wealthy landowner.[178][179]

The drawing is related to a painted portrait of Lestrange, by Holbein, in the Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, Texas;[180] a copy by a follower is in a private collection.[181] |

_1.jpg) |

|

An unidentified man[184] | c. 1532 – c. 1543 | Black and coloured chalks, white bodycolour, pen and ink, and brush and ink on pale pink prepared paper. | 27.1 × 18.9 cm | The identity of the sitter is unknown.[184] One suggestion is John Dudley, 1st Duke of Northumberland,[185] the man behind the unsuccessful attempt to install Lady Jane Grey as a Queen.[186] | |

_by_Hans_Holbein_the_Younger.jpg) |

An unidentified man[187] | 1535 | Black and coloured chalks, white bodycolour, pen and ink, and metalpoint on pale pink prepared paper. | 29.8 × 22.2 cm | The identity of the sitter is uncertain; one suggestion is Sir Ralph Sadler, who served as Privy Councillor, Secretary of State and ambassador to Scotland.[187][188][189]

The drawing is related to a painted portrait, by Holbein's workshop, in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.[188] |

|

|

An unidentified man[190] | c. 1532 – c. 1543 | Black and coloured chalks on pale pink prepared paper. | 25.9 × 20.1 cm | The identity of the sitter is unknown.[190] | |

|

An unidentified man[191] | c. 1535 | Black and coloured chalks, pen and ink, and brush and ink on pale pink prepared paper. | 27.2 × 21.0 cm | The identity of the sitter is unknown.[191]

It is possible that the drawing is a study for a roundel or a circular miniature, now lost, but recorded in a 1647 etching by Wenceslaus Hollar.[192] |

.jpg) |

|

An unidentified woman[193] | c. 1526 – c. 1528 | Black and coloured chalks. | 35.6 × 24.8 cm | The identity of the sitter is unknown.[193] | |

|

An unidentified woman[194] | c. 1532 – c. 1543 | Black and coloured chalks, pen and ink, and brush and ink on pale pink prepared paper. | 28.9 × 21.0 cm | The identity of the sitter is unknown.[194] | |

|

An unidentified woman[195] | c. 1532 – c. 1543 | Black and coloured chalks, white bodycolour, black and brown wash, pen and ink, and brush and ink on pale pink prepared paper. | 27.8 × 19.4 cm | The identity of the sitter is unknown.[195] | |

|

An unidentified woman[196] | c. 1532 – c. 1543 | Black and coloured chalks, and pen and ink on pale pink prepared paper. | 28.8 × 22.8 cm | The identity of the sitter is unknown.[196] | |

|

An unidentified woman[145] | c. 1532 – c. 1543 | Black and coloured chalks on pale pink prepared paper. | 28.5 × 21.8 cm | The identity of the sitter is unknown.[145] One suggestion is Anne Herbert, Countess of Pembroke,[144] lady-in-waiting to all six wives of Henry VIII and sister to the last wife Catherine Parr.[197]

A drawing of Anne Herbert's brother William Parr, 1st Marquess of Northampton, by Holbein, is also in the Royal Collection.[142] |

|

|

An unidentified woman[198] | c. 1532 – c. 1543 | Black and coloured chalks, and pen and ink on pale pink prepared paper. | 27.4 × 20.1 cm | The identity of the sitter is unknown.[198]

The portrait is recorded in a circular format in a 1647 etching by Wenceslaus Hollar.[199] |

|

_by_Hans_Holbein_the_Younger.jpg) |

An unidentified woman[200] | c. 1526 – c. 1528 | Black and coloured chalks. | 40.5 × 29.2 cm | The identity of the sitter is unknown.[200] | |

|

Elizabeth Vaux[201] | c. 1536 | Black and coloured chalks, white bodycolour, wash, pen and ink, brush and ink, and metalpoint on pale pink prepared paper. | 28.1 × 21.5 cm | Lady Elizabeth Vaux was the wife of Thomas Vaux, 2nd Baron Vaux of Harrowden.[201]

The drawing is a study for a painted portrait, now lost, but known through copies; an early-17th-century one is at the Hampton Court Palace, part of the Royal Collection;[202][203] another one, sometimes attributed to Holbein himself, is in the Prague Castle Picture Gallery, Czech Republic.[204] |

_-_Elizabeth_Vaux_(Prague).jpg) |

|

Thomas Vaux[183] | c. 1533 | Black and coloured chalks, pen and ink, brush and ink, white and yellow bodycolour, and metalpoint on pale pink prepared paper. | 27.9 × 29.5 cm | The sitter is Thomas Vaux, 2nd Baron Vaux of Harrowden, best remembered as a poet.[183][205]

Another drawing of Vaux by Holbein, with shorter hair, is also in the Royal Collection.[182] Royal Collection also has a Holbein's drawing of his wife Lady Elizabeth Vaux;[201] Holbein's painted portrait based on the drawing no longer survives, but is known from copies, including an early-17th-century one at the Hampton Court Palace, part of the Royal Collection,[202][203] and another one, sometimes attributed to Holbein himself, in the Prague Castle Picture Gallery, Czech Republic.[204] A drawing of his brother-in-law Thomas Lestrange is in the Royal Collection, as well;[178] a related painted portrait, by Holbein, is in the Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, Texas,[180] with an additional copy by a follower in a private collection.[181] |

|

|

Thomas Vaux[182] | c. 1536 | Black and coloured chalks on pale pink prepared paper. | 29.1 × 20.6 cm | The sitter is Thomas Vaux, 2nd Baron Vaux of Harrowden, best remembered as a poet.[182][205]

Another drawing of Vaux by Holbein, with longer hair, is also in the Royal Collection.[183] Royal Collection also has a Holbein's drawing of his wife Lady Elizabeth Vaux;[201] Holbein's painted portrait based on the drawing no longer survives, but is known from copies, including an early-17th-century one at the Hampton Court Palace, part of the Royal Collection,[202][203] and another one, sometimes attributed to Holbein himself, in the Prague Castle Picture Gallery, Czech Republic.[204] A drawing of his brother-in-law Thomas Lestrange is in the Royal Collection, as well;[178] a related painted portrait, by Holbein, is in the Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, Texas,[180] with an additional copy by a follower in a private collection.[181] |

|

|

William Warham[206] | 1527 | Black, white and coloured chalks, and traces of metalpoint. | 40.7 × 30.9 cm | William Warham was the Archbishop of Canterbury from 1503 to his death in 1532.[206]

The drawing is a study for a painted portrait, by Holbein, in the Louvre, Paris;[207] among the surviving copies are a late-16th-century one at the Lambeth Palace, the official London residence of the Archbishop of Canterbury, and an early-17th-century one in the National Portrait Gallery, London.[208] |

|

|

Thomas Wentworth[209] | c. 1532 – c. 1543 | Black and coloured chalks, pen and ink, brush and ink, and metalpoint on pale pink prepared paper. | 31.9 × 28.0 cm | Thomas Wentworth, 1st Baron Wentworth was an English courtier who went on to become the Lord Chamberlain under Edward VI.[210] | |

|

Catherine Willoughby[211] | c. 1532 – c. 1543 | Black and coloured chalks, pen and ink, and brush and ink on pale pink prepared paper. | 28.9 × 20.9 cm | Catherine Willoughby, 12th Baroness Willoughby de Eresby was the fourth wife of Charles Brandon, 1st Duke of Suffolk.[211]

A portrait miniature of Catherine, by Holbein, is at the Grimsthorpe Castle, owned by the Baroness Willoughby de Eresby.[212] |

|

|

Charles Wingfield[215] | c. 1532 – c. 1540 | Black and coloured chalks, and pen and ink on pale pink prepared paper. | 28.3 × 19.7 cm | The sitter is Sir Charles Wingfield,[215] son of the influential courtier Sir Richard Wingfield.[216] | |

_by_Hans_Holbein_the_Younger.jpg) |

Thomas Wyatt[217] | c. 1535 – c. 1537 | Black and coloured chalks, and pen and ink on pale pink prepared paper. | 37.2 × 26.9 cm | The sitter is the court poet Sir Thomas Wyatt.[217]

Another drawing of Wyatt, a very skillful copy of this one, perhaps Elizabethan, possibly by Federico Zuccari, is also in the Royal Collection.[218][219] Holbein also made a painting or drawing of Wyatt in profile, now lost, but recorded in a 1548 woodcut (published in John Leland's Naeniae, elegy in praise of Wyatt, written on his death)[220] and several later copies, including two in the National Portrait Gallery, NPG 1035 and NPG 2809.[221][222] |

|

|

Mary Zouch[225] | c. 1532 – c. 1543 | Black and coloured chalks, and pen and ink on pale pink prepared paper. | 29.6 × 21.2 cm | The exact identity of the sitter is uncertain; Jane Seymour's lady-in-waiting Mary Zouch and Anne Boleyn's close friend and lady-in-waiting Anne Gainsford have been suggested.[225] |

Kunstmuseum Basel

| Work | Title | Date | Medium | Size | Notes | Related works |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Bonifacius Amerbach[226] | c. 1525 | Black and coloured chalk, metalpoint. | 40.0 × 36.8 cm | Bonifacius Amerbach(de) taught Roman law at Basel University and became a friend of Holbein, as well as of the great humanist scholar Desiderius Erasmus, who made him his sole heir. Amberbach's collection of Holbein, expanded by his son Basilius(de), formed the core of Kunstmuseum Basel.[227]

An earlier painted portrait of Amerbach, by Holbein, is also in Kunstmuseum Basel.[228] |

|

|

Jean de Berry[229] | 1523–1524 | Black and coloured chalk. | 39.6 × 27.5 cm | The drawing was long thought to be a portrait of a living person, until in the 1870s Jacob Burckhardt discovered it was actually a study of a statue of John, Duke of Berry (another drawing by Holbein, also in Kunstmuseum Basel, records the companion statue of the Duke's wife Joan II, Countess of Auvergne).[230][231] The two sculptures date to around 1400 and are attributed to Jean de Cambrai.[230][232] Originally, they stood at the sides of the Altar of Notre-Dame la Blanche in the chapel of Sainte-Chapelle(fr), Bourges, that Holbein evidently visited during his trip to France in 1523–1524 (see 1921 reconstruction drawing of the sculptural group).[230] Saint-Chapelle was damaged by fire in 1693 and demolished in 1757; the sculptures were moved to the Bourges Cathedral, where they stand to this day.[233] During the French Revolution, in 1793, the statue was badly damaged and its head was broken off (the one currently on display is an 1844 replacement by the local sculptor Jules Dumoutet).[230] The much-damaged original head is preserved in Musée du Berry, Palais Jacques-Cœur(fr), Bourges;[234] it appears very similar to the head of the Duke's effigy, also by Jean de Cambrai, preserved in situ in the Bourges Cathedral.[230] |  |

|

Jeanne d'Auvergne[231] | 1523–1524 | Black and coloured chalk. | 39.6 × 27.5 cm | The drawing was long thought to be a portrait of a living person, until in the 1870s Jacob Burckhardt discovered it was actually a study of a statue of Joan II, Countess of Auvergne, wife of John, Duke of Berry, a companion statue of whom Holbein also sketched (the drawing is in Kunstmuseum Basel, as well).[230][229] The two sculptures date to around 1400 and are attributed to Jean de Cambrai.[230][232] Originally, they stood at the sides of the Altar of Notre-Dame la Blanche in the chapel of Sainte-Chapelle(fr), Bourges, that Holbein evidently visited during his trip to France in 1523–1524 (see 1921 reconstruction drawing of the sculptural group).[230] Saint-Chapelle was damaged by fire in 1693 and demolished in 1757; the sculptures were moved to the Bourges Cathedral, where they stand to this day.[233] During the French Revolution, in 1793, the statue was badly damaged and its head was broken off (the one currently on display is a 1913 replacement based on the Holbein's drawing).[230] Jeanne's characteristic costume has been reused by Holbein in the Duchess woodcut from the Danse Macabre series of 1525.[230] |

|

|

Nicholas Carew[36] | 1527 | Black and coloured chalk. | 54.8 × 38.5 cm | Sir Nicholas Carew was a prominent courtier and renowned jouster, executed in 1539 for his alleged part in the Exeter Conspiracy.[235]

A related painted portrait of Nicholas Carew, wearing a full jousting set of Greenwich armour,[236] by Holbein, is in the Drumlanrig Castle, part of the Buccleuch collection.[37] |

|

|

Mary Guildford[38] | 1527 | Black and coloured chalks. | 55.2 × 38.5 cm | Lady Mary Guildford was the daughter of Sir Sir Edward Wotton and the second wife of Sir Henry Guildford, one of Henry VIII’s closest friends.[102][103]

The drawing is related to a painted portrait of Mary, by Holbein, in the Saint Louis Art Museum;[40] a 16th-century copy, long thought to be the original before the discovery of the Saint Louis painting, is in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.[41] A drawing of her first husband Sir Henry Guildford, as well as a related painted portrait, both by Holbein, are in the Royal Collection.[102][104] A drawing of her second husband[33] Sir Gavin Carew is also in the Royal Collection.[32] |

|

|

Anna Meyer[237] | c. 1525 – c. 1526 | Black and coloured chalks with lead point on light green background. | 39.1 × 27.5 cm |  | |

|

Dorothea Meyer[238] | c. 1525 – c. 1526 | Black and coloured chalks with lead point on white-primed paper. | 39.5 × 28.1 cm |  | |

|

Dorothea Meyer[239] | 1516 | Silverpoint, red chalk, and traces of black pencil on white-coated paper. | 29.3 × 20.1 cm |  | |

|

Jakob Meyer[240] | c. 1525 – c. 1526 | Black and coloured chalks with lead point on light green background. | 38.3 × 27.5 cm | Preparatory for the Double Portrait of Jakob Meyer zum Hasen and Dorothea Kannengießer |  |

|

Jakob Meyer[241] | 1516 | Silverpoint, red chalk, and traces of black pencil on white-coated paper. | 28.1 × 19.0 cm |  |

See also

Notes

- ↑ "Simon George". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912208.

- 1 2 "Portrait of Simon George of Cornwall, ca. 1535–40". Städel. Retrieved 29 January 2015.

- 1 2 Rowlands 1979, p. 54

- ↑ Michael 2013, p. 670

- 1 2 "William Reskimer (d.1552)". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912237. RCIN 912237.

- ↑ "William Reskimer (?-1552)". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 404422. RCIN 404422.

- ↑ "An unidentified woman". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912190. RCIN 912190.

- ↑ Oliver at al 2006, p. 168, p.171 text + fn. 20.

- 1 2 3 "Elizabeth, Lady Audley (d.1564)". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912191. RCIN 912191.

- 1 2 "Elizabeth, Lady Audley (? - 1564)". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 422292. RCIN 422292.

- 1 2 3 "Margaret, Marchioness of Dorset (d. in or after 1535)". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912209.

- 1 2 "Lady Margaret Wotton, Marchioness of Dorset (1487 - 1541)". Weiss Gallery. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- 1 2 "Margaret Wotton, Marchioness of Dorset (d. 1535)". National Trust. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- 1 2 "Queen Anne Boleyn (c.1500-1536)". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912189.

- ↑ "Lead medal, Bust of Anne Boleyn, 1534, museum number M.9010". British Museum. Retrieved 10 February 2015.

- ↑ Rowlands and Starkey 1983, p. 91

- ↑ "Portrait of a lady, formerly thought to be Anne Boleyn". British Museum. Retrieved 29 January 2015.

- 1 2 "James Butler, later 9th Earl of Ormond and 2nd Earl of Ossory (c.1496-1546)". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912263.

- 1 2 Starkey 1981

- 1 2 Susan James. Women's Voices in Tudor Wills, 1485–1603: Authority, Influence and Material Culture, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. 20 March 2015. pg 176. Google eBook

- ↑ "Lady Borough". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912193.

- ↑ Porter, Linda. '‘Katherine the Queen’', Macmillan, 2010. pg 55.

- 1 2 "Nicholas Bourbon (c.1503-1549/50)". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912192.

- ↑ Rowlands and Starkey 1983, p. 92

- 1 2 Eric Ives. "Bourbon, Nicholas". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/70782. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- 1 2 "George Brooke, 9th Baron Cobham (c.1497-1558)". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912195.

- ↑ "Auction 977, Old Masters, 14.05.2011, 00:00, Cologne. Lot 1014. Hans Holbein the Younger, follower of. Portrait. George Brooke, Ninth Baron Cobham". Lempertz(de). Retrieved 29 January 2015.

- 1 2 "Margaret, Lady Butts (c.1485-1545)". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912264.

- ↑ "Portrait of Lady Margaret Butts". Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. Retrieved 29 January 2015.

- ↑ "Portrait of Sir William Butts, M.D." Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. Retrieved 29 January 2015.

- ↑ "The Holbein". Worshipful Company of Barbers. Retrieved 29 January 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 "Sir Gavin Carew". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912196.

- 1 2 3 4 "Carew family". tudorplace.com.ar. Retrieved 29 January 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 J. P. D. Cooper. "Carew, Sir George". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/38895. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Sir George Carew (c.1504-1545)". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912197.

- 1 2 3 "Bildnis des Sir Nicholas Carew, 1527". Kunstmuseum Basel. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- 1 2 3 Griener and Bätschmann 2012, p. 199, p. 203 fig. 203, p. 326 fn. 42

- 1 2 3 "Bildnis der Lady Mary Guildford, 1527". Kunstmuseum Basel. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- 1 2 Griener and Bätschmann 2012, p. 239 fig. 239, p. 240 fig. 240

- 1 2 3 "Mary, Lady Guildford". Saint Louis Art Museum. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- 1 2 3 "Lady Guildford (Mary Wotton, born 1500)". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 13 February 2015.

- 1 2 "Edward Fiennes de Clinton, 9th Lord Clinton, 1st Earl of Lincoln (1512-1585)". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912198.

- 1 2 "John Colet, Dean of St Paul's (1467-1519)". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912199.

- ↑ Grossmann, 1950

- ↑ Grossman 1950, pl. 52b, pl. 56

- ↑ Grossman 1950, p. 218

- 1 2 Lochman 2007, pp. 1–2, p. 3 fig. 1, p. 4 fig. 2

- ↑ "John Colet by Pietro Torrigiano". National Portrait Gallery, London. Retrieved 31 January 2015.

- ↑ Grossman 1950, p. 214, p. 216

- ↑ Grossman 1950, pp.216–218

- ↑ Grossman 1950, p. 205

- ↑ Grossman 1950, pp. 206–207 + pl. 54c

- ↑ Grossman 1950, pp. 211–213 + pl. 54a

- ↑ Grossman 1950, pp. 210–211

- ↑ Grossman 1950, p. 210 fn. 3

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Anne Cresacre (c.1511-1577)". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912270.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Lewis 1998, p. 16

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Ainsworth 1990, p. 196

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 "Cicely Heron (b.1507)". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912269.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Entwurf für das Familienbild des Thomas Morus, 1527". Kunstmuseum Basel. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Sir Thomas More, his household and descendants". Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved 31 January 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Sir Thomas More, his father, his household and his descendants". National Portrait Gallery, London. Retrieved 30 January 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Sir Thomas More and his Family (after Hans Holbein the Younger)". National Trust. Retrieved 31 January 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "John More". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912226.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Elizabeth Dauncey (b.1506)". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912228.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Sir John More (c.1451-1530)". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912224.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Sir Thomas More (1478-1535)". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912268. RCIN 912268.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Sir Thomas More (1478-1535)". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912225. RCIN 912225.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Sir Thomas More, 1527". Frick Collection. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Margaret More (1505–1544), Wife of William Roper". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- 1 2 Aikin 1826, p. 9

- ↑ "Thomas Grey, second Marquis of Dorset". Luminarium. Retrieved 31 January 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 "Edward, Prince of Wales (1537-1553)". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912200. RCIN 912200.

- 1 2 3 "Edward VI as a Child". National Gallery of Art. Retrieved 31 January 2015.

- 1 2 3 "Edward, Prince of Wales (1537-1553)". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912201. RCIN 912201.

- 1 2 3 "Margaret, Lady Elyot (c.1500-1560)". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912204.

- 1 2 3 4 "Sir Thomas Elyot (c.1490-1546)". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912203.

- ↑ Thomas Elyot (1531). The Boke named The Governour. full text online

- ↑ "John Fisher, Bishop of Rochester (c.1469-1535)". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912205.

- ↑ Richard Rex. "Fisher, John". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/9498. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ "Holy Days". Church of England. Retrieved 31 January 2015.

July 6: Thomas More, Scholar, and John Fisher, Bishop of Rochester, Reformation Martyrs, 1535

- ↑ "John Fisher, after Hans Holbein the Younger, oil on paper, 16th century, circa 1527, 21.0 × 19.1 cm, NPG 2821". National Portrait Gallery, London. Retrieved 10 February 2015.

- ↑ "Portrait of John Fisher". British Museum. Retrieved 10 February 2015.

- 1 2 3 Rowlands 1979, p. 55

- ↑ Jaffé 1965, p. 29, p. 34 fn. 36

- 1 2 "William Fitzwilliam, Earl of Southampton". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912206.

- ↑ William B. Robison. "Fitzwilliam, William". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/9663. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ Weir 2001, p. 557, fn. 37

- ↑ "William Fitzwilliam, Earl of Southampton". Fitzwilliam Museum. Retrieved 31 January 2015.

- ↑ "Sir John Gage (1479-1556)". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912207.

- ↑ David Potter. "Gage, Sir John". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/10272. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ David Porter (2002). "Sir John Gage, Tudor Courtier and Soldier (1479–1556)". The English Historical Review. 117 (474): 1109–1146. doi:10.1093/ehr/117.474.1109. JSTOR 3490799.

- 1 2 3 4 "Margaret Giggs (1508-1570)". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912229.

- 1 2 Lewis 1998, pp. 15–16

- 1 2 3 "Sir John Godsalve (c.1505-1556)". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912265.

- ↑ "Portrait of John Godsalve". Philadelphia Museum of Art. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- ↑ "Thomas Godsalve (1481–1542) und sein Sohn Sir John (etwa 1510–1556)". Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- 1 2 "Hans Holbein the Younger, Portrait of an Unknown English Lady c. 1535". Oskar Reinhart Collection 'Am Römerholz', Winterthur. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- ↑ "Bildnis der Elizabeth Widmerpole, Gattin des Sir John Godsalve". Europeana. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- 1 2 Rowlands 1985, p. 142

- 1 2 3 4 "Sir Henry Guildford (1489-1532)". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912266. RCIN 912266.

- 1 2 Keith Dockray. "Guildford, Sir Henry". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/11721. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- 1 2 "Sir Henry Guildford (1489-1532)". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 400046. RCIN 400046.

- 1 2 3 Lewis 1998, p. 17

- 1 2 "Mary, Lady Heveningham (1510/15-1570/71)". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912227.

- 1 2 Herman 2004

- ↑ Michael 2013, p. 482

- 1 2 3 "Elizabeth, Lady Hoby (c.1500-1560)". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912211.

- ↑ Hewerdine 2012, p. 200

- 1 2 P. S. Edwards. "Hoby, Sir Philip (1504/5-58), of Leominster, Herefs., Bisham, Berks. and the Blackfriars, London". The history of Parliament. Retrieved 1 February 2015. External link in

|website=(help) - 1 2 "Sir Philip Hoby (1504/5-1558)". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912210.

- ↑ "An unidentified woman". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912218. RCIN 912218.

- ↑ Parker 1945, p. 53

- 1 2 3 "Portrait of a Lady, perhaps Katherine Howard (1520-1542)". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 422293.

- 1 2 3 "Portrait Miniature of Katherine Howard". Strawberry Hill House. Retrieved 2 February 2015.

- ↑ "Portrait of a Lady, probably a Member of the Cromwell Family". Toledo Museum of Art. Retrieved 2 February 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey (1516/17-1547)". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912216. RCIN 912216.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey (1516/17-1547)". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912215. RCIN 912215.

- 1 2 3 4 "Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey (1516/17-1547)". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912213. RCIN 912213.

- 1 2 3 4 "Hans Holbein, o Jovem. O Poeta Henry Howard, Conde de Surrey". São Paulo Museum of Art. Retrieved 2 February 2015.

- 1 2 3 "Thomas Howard, Third Duke of Norfolk (1473-1554)". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 404439.

- 1 2 3 4 "Frances, Countess of Surrey (1517-1577)". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912214.

- 1 2 "Mary, Duchess of Richmond and Somerset (c.1519-c.1555)". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912212.

- 1 2 "Lady Lister". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912219.

- ↑ Parker 1945, p. 41

- 1 2 "Princess Mary, later Queen (1516-1558)". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912220.

- 1 2 "An unidentified man". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912221. RCIN 912221.

- ↑ Buck 1999, p. 71

- 1 2 "Joan, Lady Meutas (d.1577)". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912222.

- ↑ D. M. Ogier. "Mewtas [Mewtis], Sir Peter". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/68013. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ "Die heilige Maria Magdalena als Büsserin, zwischen 1532–1536". Kunstmuseum Basel. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- ↑ Foister 2006, p. 81; Parker 1945, pp. 41–42

- 1 2 "Mary, Lady Monteagle (1510-before 1544)". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912223.

- ↑ Weir 1991, p. 365

- ↑ Eric Ives. "More, Sir John". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/19183. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- 1 2 Retha Warnicke. "More [née Harpur; other married name Middleton], Alice, Lady More". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/46912. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- 1 2 "Lady Alice More (c.1474 - c.1551)". Weiss Gallery, London. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- 1 2 Hall 1990

- 1 2 "Grace, Lady Parker (1515- by 1549)". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912230.

- ↑ Parker 1945, p. 56

- 1 2 3 "William Parr, later Marquess of Northampton (1513-1571)". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912231.

- ↑ Susan E. James. "Parr, William". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/21405. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- 1 2 James 2009, p.133, p. 322 fn. 56, "She may also have been the subject of one of Holbein's most expressive drawings, executed during the period Anne served as a gentlewoman of the queen's privy chamber. [56] <...> R.L. 12256"

- 1 2 3 "An unidentified woman". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912256. RCIN 912256.

- 1 2 "Sir Thomas Parry (c.1515-1560)". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912232.

- ↑ Jonathan Hughes. "Parry, Sir Thomas". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/21433. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- 1 2 3 "John Poyntz (c.1485-1544)". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912233.

- 1 2 3 T. F. T. Baker. "Poyntz, John (c.1485-1544), of Alderley, Glos". The history of Parliament. Retrieved 4 February 2015. External link in

|website=(help) - 1 2 "Portrait of John Poyntz". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- 1 2 3 "Sir Nicholas Poyntz (c.1510-1556)". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912234.

- ↑ Alasdair Hawkyard. "Sir Nicholas Poyntz". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/70798. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ "Sir Nicholas Poyntz". National Portrait Gallery, London. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- ↑ Grossman 1951, p. 41 fig.3, pp. 43–44

- ↑ "Sir Nicholas Poyntz (1510–1557)". National Trust. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- ↑ "An unidentified man". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912235. RCIN 912235.

- ↑ Parker 1945, p. 58

- 1 2 3 "Lady Ratcliffe". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912236.

- ↑ Parker 1945, p.41

- 1 2 3 "Elizabeth, Lady Rich (d.1558)". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912271.

- 1 2 "Lady Rich (Elizabeth Jenks, died 1558)". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 6 February 2015.

- 1 2 3 "Sir Richard Rich, later 1st Baron Rich (1496/7-1567)". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912238.

- ↑ P. R. N. Carter. "Rich, Richard, first Baron Rich". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/23491. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ "Knepp fire (Transcribed from the West Sussex County Times and Standard, 23 January 1904)".

Among other works of art, the following celebrated paintings were burnt to ashes: <...> “Sir Richard Rich, Chancellor to Edward VI” by Holbein

- 1 2 3 "Francis Russell, later 2nd Earl of Bedford (1526/7-1585)". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912240.

- 1 2 3 "John Russell, 1st Earl of Bedford (1485-1555)". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912239.

- ↑ Diane Willen. "Russell, John". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/24319. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- 1 2 3 "Queen Jane Seymour (1508/9-1537)". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912267.

- ↑ Bischoff 2010; quoted at the Google Cultural Institute profile for the Vienna portrait: Jane Seymour, Queen of England, 1536

- ↑ "Portrait of Jane Seymour (1509?-1537), c. 1540". Mauritshuis, The Hague. Retrieved 7 February 2015.

- ↑ "Henry VII, Elizabeth of York, Henry VIII and Jane Seymour". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 405750.

- ↑ "Sir William Sharington (c.1495-1553)". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912241.

- ↑ C. E. Challis. "Sharington, Sir William". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/25205. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- 1 2 3 "Sir Richard Southwell (1502/3-1564)". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912242.

- ↑ "Sir Richard Southwell". Uffizi. Retrieved 7 February 2015.

- 1 2 "Edward Stanley, 3rd Earl of Derby (1509-1572)". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912243.

- ↑ Parker 1945, p. 50

- 1 2 3 4 "Sir Thomas Lestrange (c.1490-1545)". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912244.

- ↑ Joy Rowe. "Lestrange, Sir Thomas". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/16515. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- 1 2 3 Pillsbury and Jordan 1985, p. 409

- 1 2 3 Oestmann 1994, frontispiece

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Thomas, 2nd Baron Vaux (1509-1556)". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912246. RCIN 912246.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Thomas, 2nd Baron Vaux (1509-1556)". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912245. RCIN 912245.

- 1 2 "An unidentified man". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912260. RCIN 912260.

- ↑ James 2009, p. 179 fig. 18

- ↑ David Loades. "Dudley, John". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/8156. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- 1 2 "An unidentified man". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912259. RCIN 912259.

- 1 2 "Portrait of a Man (Sir Ralph Sadler?)". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 9 February 2015.

- ↑ Gervase Phillips. "Sadler, Sir Ralph". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/24462. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- 1 2 "An unidentified man". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912262. RCIN 912262.

- 1 2 "An unidentified man". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912258. RCIN 912258.

- ↑ Foister 2006, p. 148; Parker 1945, p. 44

- 1 2 "An unidentified woman". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912217. RCIN 912217.

- 1 2 "An unidentified woman". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912253. RCIN 912253.

- 1 2 "An unidentified woman". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912254. RCIN 912254.

- 1 2 "An unidentified woman". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912255. RCIN 912255.

- ↑ James 2009, p. 81

- 1 2 "An unidentified woman". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912257. RCIN 912257.

- ↑ "Plate Number: P1549". University of Toronto Libraries. Retrieved 9 February 2015.

- 1 2 "An unidentified woman". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912273. RCIN 912273.

- 1 2 3 4 "Elizabeth, Lady Vaux (1509-1556)". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912247. RCIN 912247.

- 1 2 3 Rebecca Wire. "Elizabeth, Lady Vaux (Hampton Court)". flickr. Retrieved 9 February 2015.

- 1 2 3 "Elizabeth Cheyne, Lady Vaux (1505-1556)". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 402953. RCIN 402953.

- 1 2 3 Mark L. Van Name (22 April 2013). "Meanwhile, back at the castle". Retrieved 9 February 2015.

- 1 2 H. R. Woudhuysen. "Vaux, Thomas". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/28163. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- 1 2 "William Warham (c.1450-1532), Archbishop of Canterbury". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912272.

- ↑ "William Warham". Louvre. Retrieved 9 February 2015.

- ↑ "Double Take: Versions and Copies of Tudor Portraits". National Portrait Gallery, London. Retrieved 9 February 2015.

- ↑ "Thomas, 1st Baron Wentworth (1501-1551)". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912248.

- ↑ P. R. N. Carter. "Wentworth, Thomas". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/29053. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- 1 2 "Katherine, Duchess of Suffolk (1519-1580)". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912194.

- ↑ de Lisle, p. xv; Franklin-Harkrider, p. 15

- ↑ "Henry Brandon, 2nd Duke of Suffolk (1535-1551)". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 422294.

- ↑ "Charles Brandon, 3rd Duke of Suffolk (1537/8-1551)". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 422295.

- 1 2 "Sir Charles Wingfield (1513-1540)". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912249.

- ↑ Mary L. Robertson. "Wingfield, Sir Richard". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/29739. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- 1 2 "Sir Thomas Wyatt (c.1503-1542)". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912250. RCIN 912250.

- ↑ "Sir Thomas Wyatt (c.1503-1542)". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912251. RCIN 912251.

- ↑ Parker 1945, p. 54

- ↑ Foister 2006, p. 56; Strong 1969, p. 339

- ↑ "Sir Thomas Wyatt, after Hans Holbein the Younger, circa 1540, oil on panel, 47 cm diameter". National Portrait Gallery, London. Retrieved 10 February 2015.

- ↑ "Sir Thomas Wyatt, after Hans Holbein the Younger, 16th century, circa 1540, oil on panel, 31.7 cm diameter". National Portrait Gallery, London. Retrieved 10 February 2015.

- ↑ "Hans Holbein dit le Jeune, Sir Henry Wyatt dit autrefois Milord Cromwell puis Thomas More (Mort en 1537)". Louvre. Retrieved 10 February 2015.

- ↑ "Lady Lee (Margaret Wyatt, born about 1509)". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 10 February 2015.

- 1 2 "Mary Zouch (?)". Royal Collection Trust. Inventory no. 912252.

- ↑ "Bonifacius Amerbach, um 1525". Kunstmuseum Basel. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- ↑ Müller 2006, p. 331

- ↑ Nuechterlein 2011, p. 60 fig. 37

- 1 2 "Jean de France, Herzog von Berry, um 1523/24". Kunstmuseum Basel. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Grossmann 1950, pp. 229–232 + pl. 58a–e

- 1 2 "Jeanne de Boulogne, Herzogin von Berry, 1523/24". Kunstmuseum Basel. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- 1 2 Erlande-Brandenburg 1980

- 1 2 Husband 2008, p. 13, p. 29

- ↑ "Tête originale du priant de Jean, duc de Berry". Joconde (in French). Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- ↑ Stanford Lehmberg. "Carew, Sir Nicholas". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/4633. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ Mann 1951, p. 383

- ↑ "Bildnis der Anna Meyer, um 1525/26". Kunstmuseum Basel. Retrieved 13 February 2015.

- ↑ "Bildnis der Dorothea Meyer, geborene Kannengiesser, um 1525/26". Kunstmuseum Basel. Retrieved 13 February 2015.

- ↑ "Bildnis der Dorothea Meyer, geb. Kannengiesser, 1516". Kunstmuseum Basel. Retrieved 13 February 2015.

- ↑ "Bildnis des Jacob Meyer zum Hasen, um 1525/26". Kunstmuseum Basel. Retrieved 13 February 2015.

- ↑ "Bildnis des Jacob Meyer zum Hasen, 1516". Kunstmuseum Basel. Retrieved 13 February 2015.

References

- Lucy Aikin (1826). Memoirs of the court of Queen Elizabeth. 1. google books preview

- Maryan Ainsworth (1990). "'Paternes for Phiosioneamyes': Holbein's Portraiture Reconsidered". The Burlington Magazine. 132 (1044): 173–186. JSTOR 884250.

- Cäcilia Bischoff (2010). Masterpieces of the Picture Gallery. Vienna: Kunsthistorisches Museum.

- Stephanie Buck (1999). Hans Holbein. Cologne: Könemann(de). ISBN 3829025831.

- Alain Erlande-Brandenburg (1980). "Jean de Cambrai, sculpteur de Jean de France, duc de Berry". Monuments et mémoires de la Fondation Eugène Piot. 63 (63): 143–186. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- Susan Foister (2006). Holbein in England. London: Tate. ISBN 1854376454.

- Melissa Franklin-Harkrider (2008). Women, Reform and Community in Early Modern England. Boydell Press. ISBN 9781843833659. google books preview

- Pascal Griener; Oskar Bätschmann(de) (2014). Hans Holbein (2 ed.). London: Reaktion Books. ISBN 9781780232324. google books preview

- Fritz Grossmann (1950). "Holbein, Torrigiano and Some Portraits of Dean Colet: A Study of Holbein's Work in Relation to Sculpture". Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes. 13 (3/4): 202–236. JSTOR 750213.

- Fritz Grossmann (1951). "Holbein Studies - I". The Burlington Magazine. 93 (575): 39–44. JSTOR 870632.

- Noeline Hall (1990). "Henry Patenson — Sir Thomas More's Fool" (PDF). Moreana. 27 (101–102): 75–86. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- Peter C. Herman (1994). Rethinking the Henrician Era: Essays on Early Tudor Texts and Contexts. Champaign, Illinois: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 9780252063404. google books preview

- Anita Hewerdine (2012). The Yeomen of the Guard and the Early Tudors: the Formation of a Royal Bodyguard. London: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 9781848859838. google books preview

- Timothy Bates Husband (2008). The Art of Illumination: The Limbourg Brothers and the Belles Heures of Jean de France, Duc de Berry. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 9781588392947. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- Michael Jaffé (1965). "Rubens as a Collector of Drawings. Part Two". Master Drawings. 3 (1): 21–35+65–83. JSTOR 1552780.

- Susan E. James (2009). Catherine Parr: Henry VIII's Last Love. The History Press. ISBN 075244591X. google books preview

- Lesley Lewis (1998). The Thomas More Family Group Portraits After Holbein. Gracewing Publishing. ISBN 9780852444665. google books preview

- Leanda de Lisle (2009). The Sisters Who Would Be Queen. Random House. ISBN 9780345516688. google books preview

- James Mann (1951). "The Exhibition of Greenwich Armour at the Tower of London". The Burlington Magazine. 93 (585): 378–383. JSTOR 870886.

- Christian Müller (2006). Hans Holbein the Younger: The Basel Years, 1515–1532. Munich: Prestel Publishing. ISBN 9783791335803.

- Erika Michael (2013). Hans Holbein the Younger: A Guide to Research. Routledge. ISBN 9781136781148. google books preview

- Jeanne Nuechterlein (2011). Translating Nature Into Art: Holbein, the Reformation, and Renaissance Rhetoric. Penn State Press. ISBN 9780271036922. google books preview

- Cord Oestmann (1994). Lordship and Community: The Lestrange Family and the Village of Hunstanton, Norfolk, in the First Half of the Sixteenth Century. Boydell Press. ISBN 9780851153513. google books preview

- Lois Oliver; Victoria Button; Alan Derbyshire; Nick Frayling; Rob Withnall (2006). "New Evidence Towards an Attribution to Holbein of a Drawing in the Victoria and Albert Museum". The Burlington Magazine. 148 (1236): 168–172. JSTOR 20074338.

- K. T. Parker (1945). The Drawings of Hans Holbein at Windsor Castle.

- Edmund Pillsbury; William Jordan (1985). "Recent Painting Acquisitions - II: The Kimbell Art Museum: Supplement". The Burlington Magazine. 127 (987): 409–418. JSTOR 882120.

- John Rowlands (1979). "Holbein and the Court of Henry VIII [Exhibition Catalogue] (Review)". Master Drawings. 17 (1): 53–56. JSTOR 1553456.

- John Rowlands; David Starkey (1983). "An Old Tradition Reasserted: Holbein's Portrait of Queen Anne Boleyn". The Burlington Magazine. 125 (959): 88+90–92. JSTOR 881170.

- John Rowlands (1985). Holbein: The Paintings of Hans Holbein the Younger. Boston: David R. Godine. ISBN 0879235780.

- David Starkey (1981). "Holbein's Irish Sitter?". The Burlington Magazine. 123 (938): 300–301+303. JSTOR 880241.

- Alison Weir (1991). The Six Wives of Henry VIII. Grove Press. ISBN 9780802198754. google books preview

- Alison Weir (2001). Henry VIII: King and Court. Random House. ISBN 9781446449233. google books preview

External links