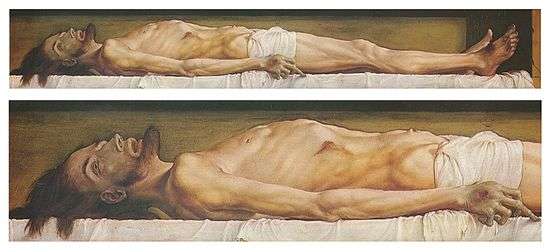

The Body of the Dead Christ in the Tomb

The Body of the Dead Christ in the Tomb is an oil and tempera on limewood painting created by the German artist and printmaker Hans Holbein the Younger between 1520–22. The work shows a life-size, grotesque depiction of the stretched and unnaturally thin body of Jesus Christ lying in his tomb. Holbein shows the dead Son of God after he has suffered the fate of an ordinary human.

Description

The painting is especially notable for its dramatic dimensions (30.5 cm x 200 cm),[1] and the fact that Christ's face, hands and feet, as well as the wounds in his torso, are depicted as realistic dead flesh in the early stages of putrefaction. His body is shown as long and emaciated while eyes and mouth are left open.[2]

Christ is shown with three visible wounds; on his hand, side and feet. Discussing the artist's use of unflinching realism, Bätschmann and Griener noted that Christ's raised and extended middle finger appears to "reach towards the beholder", while his strands of hair "look as if they are breaking through the surface of the painting".[2] Above the body, angels holding instruments of the Passion bear an inscription in brush on paper inscribed with the Latin words "IESVS·NAZARENVS·REX·IVDÆORVM" (Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews).[3]

Background

In common with many artists of the early Protestant Reformation, Holbein was fascinated with the macabre. His father, Hans Holbein the Elder, took him to see Matthias Grünewald's altarpiece in Isenheim, a city in which the elder also received a number of commissions from the local hospice.[2] In common with the religious traditions of the 1520s the work was intended to evoke piety and follows the intentions of Grünewald, who in his altarpiece set out to instill feelings of both guilt and empathy in the viewer.[4]

It is unknown for what purpose the painting was created. Various suggestions have been offered, including as a predella for an altarpiece, a free-standing work, or an ornament for a sepulchre.[1] In 1999, the art historians Oskar Bätschmann and Pascal Griener raised the possibility that the panel was intended to form part of a Holy Tomb, perhaps as a lid to be laid over a sepulchre.[4] It is known that Holbein used a body fished out of the Rhine as a model for the work.

Commentary

The panel has attracted fascination and praise since it was created. The Russian author Fyodor Dostoevsky was captivated by the work. In 1867, his wife had to drag him away from the panel lest its grip on him induce an epileptic fit.[4] Dostoevsky saw in Holbein an impulse similar to one of his own main literary preoccupations: the pious desire to confront Christian faith with everything that negated it, in this case the laws of nature and the stark reality of death.[5] In his 1869 novel The Idiot, the character Prince Myshkin, having viewed a copy of the painting in the home of Rogozhin, declares that it has the power to make the viewer lose his faith.[6] The character of Ippolit Terentyev, an articulate exponent of atheism and nihilism who is himself near death, engages in a long philosophical discussion of the painting, claiming that it demonstrates the victory of 'blind nature' over everything, including even the most perfect and beautiful of beings.[7]

Literary theorist Julia Kristeva included a psychoanalysis of the painting in her book Black Sun: Depression and Melancholia. "Does Holbein forsake us, as Christ, for an instant, had imagined himself forsaken?," she asks. "Or does he, on the contrary, invite us to change the Christly tomb into a living tomb, to participate in the painted death and thus include it in our own life, in order to live with it and make it live?"[8]

The effect of the open eyes and mouth has been described by the art critic Michel Onfray as giving the impression that "the viewer sees Christ seeing: he might also perceive what death has in store, because he's staring at the heavens, while his soul is probably there already. No-one has taken the trouble to close his mouth and his eyes. Or else Holbein wants to tell us that, even in death, Christ still looks and speaks."[1]

Notes

- 1 2 3 Onfray, Michel. "The Body of the Dead Christ in the Tomb (1521) Archived 2009-05-13 at the Wayback Machine.". Tate Etc., 2006. Retrieved on May 4, 2009.

- 1 2 3 Bätschmann & Griener, 88

- ↑ "The Body of the Dead Christ in the Tomb". Web Gallery of Art. Retrieved on May 4, 2009.

- 1 2 3 Bätschmann & Griener, 89

- ↑ Frank, Joseph (2010). Dostoevsky A Writer in His Time. Princeton University Press. p. 550.

- ↑ Meyers, 136–147

- ↑ Dostoevsky, Fyodor (2004). The Idiot. Penguin Books. pp. 475–477.

- ↑ Kristeva, Julia (1989). p 113

Sources

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to The Body of the Dead Christ in the Tomb. |

- Bätschmann, Oskar & Griener, Pascal. Hans Holbein. Reaktion Books, 1999. ISBN 1-86189-040-0

- Meyers, Jeffrey. Holbein and the Idiot in: Meyers, Jeffrey: Painting and the Novel. Manchester University Press, 1975.

- Kristeva, Julia. Black Sun: Depression and Melancholia. New York: Columbia University Press, 1989.