Leschi (Native American leader)

| Leschi | |

|---|---|

Chief Leschi | |

| Nisqually leader | |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

1808 Eatonville, Washington |

| Died |

February 19, 1858 Lake Steilacoom |

| Cause of death |

Execution by hanging 47°10′43″N 122°32′31″W / 47.178575°N 122.542065°W |

| Resting place |

Puyallup Tribal Cemetery – Tacoma, Washington 47°14′19″N 122°23′56″W / 47.2386°N 122.3989°W |

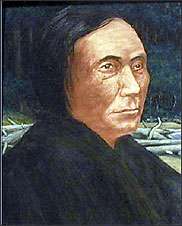

Chief Leschi (/ˈlɛʃaɪ/; 1808 – February 19, 1858) was chief of the Nisqually Native American tribe. He was hung for murder in 1858, but exonerated in 2004.

Life

Leschi was born in 1808 near what is today Eatonville, Washington, to a Nisqually chief and a Klickitat woman.[1] He was appointed chief by Isaac Stevens, first governor of Washington Territory, to represent the Nisqually and Puyallup tribes at the Medicine Creek Treaty council of December 26, 1854, which ceded to the United States all or part of present-day King, Pierce, Lewis, Grays Harbor, Mason, and Thurston Counties and stipulated that the American Indians inhabiting the area move to reservations. Some maintain that Leschi either refused to sign (and had his "X" forged by another) or signed under protest. The historical record is unclear on this point. However, he did argue that the reservation designated for the Nisqually tribe was a rocky piece of high ground unsuited to growing food and cut off from access to the river that provided the mainstay of their livelihood, salmon.[2]

On June 11, 1855, Governor Isaac I. Stevens forced representatives from the Yakima, Nez Perce, Walla Walla, Umatilla and Cayuse tribes to sign a treaty in which the various tribes signed away vast amounts of land in return for money, reservations, and other provisions. Although the treaty stated that white miners would not be allowed on reservation lands, miners frequently passed through these lands, stealing horses from the tribes and abusing Native American women.[1] The Yakima responded by killing some miners. When Indian sub-agent, Andrew J. Bolon tried to investigate the murders, he was killed, leading to fighting between Major Haller's troops and the Yakima. This conflict marked the start of the Yakima War (1855–56).[3] Leschi was charged for these murders in part, because of his participation in the Yakima War of 1855-1858, and for his role in the "Battle in Seattle" which took place in January, 1856.[1] Convinced that white settlers were cooperating with Leschi, Stevens declared martial law over Pierce County on April 2, 1856. (Stevens was later charged with contempt of court in relation to this declaration; as governor, however, he pardoned himself.[4])

The murder of Moses took place October 30, 1855, at Connell's Prairie or Tenalcut Prairie, as it was also known. Seven Washington Territorial Volunteers were here ambushed by Indians. Two of the seven, A. Benton Moses and Joseph Miles, were killed. A year later, when hostilities had quieted down somewhat, Isaac I. Stevens, governor of Washington Territory, requested federal troops to deliver up for trial five Indians. One of them was Leschi, charged with the murder of Moses. The federal troops had, however, concluded a peace with Leschi, who had fled east of the Cascades when his war failed. Yet Stevens remained adamant, and the federal troops agreed to find Leschi. Fifty blankets were offered for information leading to the arrest and capture of Leschi, and the temptation proved too strong. Sluggia, nephew of Leschi, and Eli-ku-kah, a Nisqually, delivered him into the hands of the whites.[5] Leschi was taken into custody in early November 1856, and his brother Quiemuth turned himself in shortly thereafter. Quiemuth was murdered on November 18, 1856, by an unknown assailant, in Governor Stevens' office in Olympia, where he was being held for the night on his way to the jail at Fort Steilacoom, now in Lakewood, Washington. Leschi himself was put on trial on November 17, 1856 for the murder of Colonel Moses, which he denied having committed. His first trial resulted in a hung jury because of the judge's instruction that killing of combatants during wartime did not constitute murder. The second trial began in March 18, 1857 in which this instruction was not given and his lawyers, Frank Clark and William Wallace, were not allowed to introduce potentially exonerating evidence. He was convicted and sentenced to death, to be hanged June 10, 1857.[1]

One supporter, William Fraser Tolmie, petitioned the new governor, LaFayette McMullen, to pardon Leschi, but the governor refused. Another supporter, United States Army officer August Kautz, published two issues of a newspaper defending Leschi. The execution of Leschi was delayed until January 22, 1858 after the appeal to the Territorial Supreme Court.[1] Titled the Truth Teller, the newspaper's masthead stated: "Devoted to the Dissemination of Truth and the Suppression of Humbug." Tolmie's petition and the front page of the Truth Teller are reprinted in Ezra Meeker's 1905 history, The Tragedy of Leschi.[6] Meeker was one of two who voted for acquittal on the first hung jury trial.

Execution

Leschi's execution was initially scheduled for January 22, 1858, but his supporters arranged an elaborate plot in which the Pierce County sheriff, George Williams, allowed himself to be arrested by sympathetic members of the United States Army rather than carry out the execution. On February 19, 1858, Leschi was hanged in a small valley, from a hastily constructed gallows near Lake Steilacoom, on land which later became a golf course and is now housing. There is a small monument nearby in a strip mall in Lakewood. The hangman is reported to have later said "I felt then I was hanging an innocent man, and I believe it yet."

Legacy

Roughly three decades later, Frederick J. Grant named the Leschi neighborhood in Seattle after the chief in the late 1880s. Today, the neighborhood and its waterfront park; schools in Seattle and Puyallup; and streets in Seattle, Lakewood, Steilacoom, Anderson Island, and Olympia, bear his name. Additionally, the MOUT site at Joint Base Lewis-McChord is named Leschi Town in his honor and a fireboat of the Seattle Fire Department, Leschi (fireboat) also bears his name.

In March 2004, both houses of the Washington state legislature passed resolutions stating that Leschi was wrongly convicted and executed and asked the state supreme court to vacate Leschi's conviction. The court's chief justice, however, said that this was unlikely to happen, since it was not at all clear that the state court had jurisdiction in a matter decided 146 years earlier in a territorial court. On December 10, 2004, Chief Leschi was exonerated by a unanimous vote by a Historical Court of Inquiry following a definitive trial in absentia.[7]

Category

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Schmitt, Martin (1949). "The Execution of Chief Leschi and the "Truth Teller"". Oregon Historical Quarterly. 50 (1): 30–39. JSTOR 20611895.

- ↑ Carpenter, Cecelia Svinth (1977). They Walked Before: The Indians of Washington State. Tacoma, Washington: Washington State American Revolution Bicentennial Commission. p. 29. ISBN 0-917048-04-0.

- ↑ Blee, Lisa (2008). Framing Chief Leschi: Narratives and the Politics of Historical Justice in the South Puget Sound. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses.

- ↑ "Governor Stevens' Famous Pardon of Himself". Washington Historical Quarterly. 25 (3). 1934.

- ↑ Bancroft, H.H. (1980). History of Washington, Idaho, and Montana. pp. 377–78.

|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ↑ Meeker, Ezra (1905). Pioneer Reminiscences of Puget Sound, the Tragedy of Leschi. Seattle, WA: Lowman & Hanford Stationery and Print. Co. OCLC 667877082. Retrieved June 21, 2013.

- ↑ "Court acquits Indian chief hanged in 1858". Associated Press. 2004-12-14.

Further reading

- Kluger, Richard (2011). The bitter waters of Medicine Creek: a tragic clash between white and native America. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 9780307268891. Retrieved April 3, 2016.

External links

- Leschi: Justice In Our Time, provided by the Washington State Historical Society

- Leschi at Find a Grave