Gar

| Gar | |

|---|---|

| |

| Spotted gar (Lepisosteus oculatus) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Subclass: | Neopterygii |

| Infraclass: | Holostei |

| Order: | Lepisosteiformes O. P. Hay, 1929 |

| Family: | Lepisosteidae Cuvier, 1825 |

| Genera | |

| |

Gars (or garpike) are members of the Lepisosteiformes (or Semionotiformes), an ancient holosteian order of ray-finned fish; fossils from this order are known from the Late Jurassic onwards. The family Lepisosteidae includes seven living species of fish in two genera that inhabit fresh, brackish, and occasionally marine, waters of eastern North America, Central America and the Caribbean islands.[2][3] Gars have elongated bodies that are heavily armored with ganoid scales,[4] and fronted by similarly elongated jaws filled with long, sharp teeth. All of the gars are relatively large fish, but the alligator gar (Atractosteus spatula) is the largest, as specimens have been reported to be 3 m (9.8 ft) in length;[5] however, they typically grow to 2 m (6.5 ft) and weigh over 45 kg (100 lb).[6] Unusually, their vascularised swim bladders can function as lungs,[7] and most gars surface periodically to take a gulp of air. Gar flesh is edible and the hard skin and scales of gars are used by humans; however their eggs are highly toxic.

Etymology

The name gar was originally used for a species of needlefish (Belone belone) found in the North Atlantic and likely taking its name from the Old English word for "spear".[8] Belone belone is now more commonly referred to as the "garfish" or "gar fish" to avoid confusion with the North American gars of the family Lepisosteidae.[9] Confusingly, the name "garfish" is commonly used for a number of other species of the related genera Strongylura, Tylosurus and Xenentodon of the family Belonidae.

The genus name Lepisosteus comes from the Greek lepis meaning "scale" and osteon meaning "bone".[10] Atractosteus is similarly derived from Greek, in this case from atraktos, meaning arrow.[11]

Distribution

Fossil gars are found in Europe, India, South America, and North America, indicating that in times past, these fish had a wider distribution than they do today. Gars are considered to be a remnant of a group of bony fish that flourished in the Mesozoic, and are most closely related to the bowfin. The distribution of the Gar Lepisosteidae in North America, lies mainly in the shallow, brackish waters off of Texas and Louisiana, and off the eastern coast of Mexico.[12][13] A few populations are also present in the Great Lakes region of the United States, living in similar shallow waters.[14]

Anatomy

Scales

Gar bodies are elongated, heavily armored with ganoid scales, and fronted by similarly elongated jaws filled with long, sharp teeth. Their tails are heterocercal, and the dorsal fins are close to the tail.[15]

Swim bladder

As their vascularised swim bladders can function as lungs,[7] most gars surface periodically to take a gulp of air, doing so more frequently in stagnant or warm water when the concentration of oxygen in the water is low. Experiments on the swim bladder has shown that the temperature of the water affects which respiration method the gar will use: aerial or aquatic. They will increase the aerial breathing rate (breathing air) as temperature of the water is increased. Gars can live completely submerged in oxygenated water without access to air and remain healthy while also being able to survive in deoxygenated water if allowed access to air.[16] This adaptation can be the result of environmental pressures and behavioral factors.[17] As a result of this organ, they are extremely resilient and able to tolerate conditions that most other fish could not survive in.

Pectoral girdle

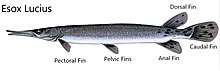

The gar has paired appendages, including pectoral fins, pelvic fins, while also having an anal fin, caudal fin, and a dorsal fin.[18] The bone structures within the fins are important to study as they can show homology throughout the fossil record. Specifically, the pelvic girdle resembles that of other actinopterygians yet still having some of its own characteristics. Gars have a postcleithrun - which is a bone that is lateral to the scapula, but do not have postpectorals. Proximally to the postcleithrum, the supracleithrum is important as it plays a critical role in opening the gar's jaws. This structure has a unique internal coracoid lamina only present in the Gar species. Proximal to the supracleithrum is the posttemporal bone, which is significantly smaller than other actinopterygians. Gars also have no clavicle bone, although there have been observations of elongated plates within the area.[19]

Morphology

All the gars are relatively large fish, but the alligator gar Atractosteus spatula is the largest. The largest alligator gar ever caught and officially recorded was 8 ft 5 1⁄4 in (2.572 m) long, weighed 327 lb (148 kg), and was 47 in (120 cm) around the girth.[20] Even the smaller species, such as Lepisosteus oculatus, are large, commonly reaching lengths of over 60 cm (2.0 ft), and sometimes much more.[21]

Ecology

Gars tend to be slow-moving fish except when striking at their prey. They prefer the shallow and weedy areas of rivers, lakes, and bayous, often congregating in small groups.[2] They are voracious predators, catching their prey with their needle-like teeth, obtained with a sideways strike of the head.[21] They feed extensively on smaller fish and invertebrates such as crabs.[5] Gars are found across much of North America (for example Lepisosteus osseus).[2] Although gars are primarily found in freshwater habitats, several species enter brackish waters and a few, most notably Atractosteus tristoechus, are sometimes found in the sea. Some gars travel from lakes and rivers through sewers to get to ponds.[2][22]

Species

The gar family contains seven extant species, in two genera:[7]

| Cladogram of living gars[23] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

Family Lepisosteidae

- Genus Atractosteus Rafinesque, 1820

- †Atractosteus africanus (Arambourg & Joleaud, 1943) [24]

- Atractosteus spatula (Lacépède, 1803) (alligator gar)

- Atractosteus tristoechus (Bloch & J. G. Schneider, 1801) (Cuban gar)

- Atractosteus tropicus Gill, 1863 (tropical gar)

- Genus Lepisosteus Linnaeus, 1758

- †Lepisosteus bemisi Grande, 2010

- †Lepisosteus cominatoi Santos, 1984

- †Lepisosteus fimbriatus (Wood 1846)

- †Lepisosteus indicus (Woodward, 1908)

- Lepisosteus oculatus Winchell, 1864 (Spotted gar)

- †Lepisosteus opertus Estes, 1964

- Lepisosteus osseus (Linnaeus, 1758) (Longnose gar)

- Lepisosteus platostomus Rafinesque, 1820 (Shortnose gar)

- Lepisosteus platyrhincus DeKay, 1842 (Florida gar)

Roe

.jpg)

Gar flesh is edible, and sometimes available in markets, but unlike the sturgeon they resemble, their eggs are highly toxic to humans.[25] Gar eggs are toxic because of a protein toxin called ichthyotoxins.[26] The protein can be denatured when brought to a temperature of 120 degrees celsius.[27] When cooking roe, the temperature does not typically get that high so the protein stays intact and causes severe symptoms. It was once thought that the production of the toxin in gar roe was an evolutionary adaptation to provide protection for the eggs. However, bluegills and channel catfish were fed gar eggs and remained healthy, even though they are the natural predators of the gar eggs. Crayfish were not immune to the toxin and most of the crayfish that ate the roe died. The immunity to the ichthyotoxins in bluegills and catfish suggests that the toxin came about for a reason other than keeping the gar eggs safe. It may just be a coincidence that the roe is toxic to humans and crayfish.[26]

Significance to humans

Several species are traded as aquarium fish.[21] The hard skin and scales of the gar were used by humans. Native Americans used the scales of the gar as arrowheads, native Caribbeans used the skin for breastplates, and early American pioneers covered the blades of their plows in gar skin.[28] Not much is known about the precise function of the gar in Native American religion and culture, but besides using the gar, Creek and Chickasaw people have ritual "garfish dances".[29]

References

- 1 2 Paulo M. Brito; Jésus Alvarado-Ortega; François J. Meunier (2017). "Earliest known lepisosteoid extends the range of anatomically modern gars to the Late Jurassic". Scientific Reports. 7: Article number 17830. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-17984-w.

- 1 2 3 4 "Family Lepisosteidae - Gars". Retrieved 2007-04-21.

- ↑ Sterba, G: Freshwater Fishes of the World, p. 609, Vista Books, 1962

- ↑ Sherman, Vincent R.; Yaraghi, Nicholas A.; Kisailus, David; Meyers, Marc A. (2016-12-01). "Microstructural and geometric influences in the protective scales of Atractosteus spatula". Journal of The Royal Society Interface. 13 (125): 20160595. doi:10.1098/rsif.2016.0595. ISSN 1742-5689. PMC 5221522. PMID 27974575.

- 1 2 "Atractosteus spatula - Alligator gar". Retrieved 2007-07-19.

- ↑ "Atractosteus spatula". Florida Museum of Natural History. Retrieved 2016-04-21.

- 1 2 3 Froese, Rainer, and Daniel Pauly, eds. (2009). "Lepisosteidae" in FishBase. January 2009 version.

- ↑ "Gar". Retrieved 2007-04-21.

- ↑ "Common Names of Belone belone". Archived from the original on 2007-10-19. Retrieved 2007-04-21.

- ↑ "Genera reference detail". Retrieved 2007-04-21.

- ↑ "Genera reference detail". Retrieved 2016-02-21.

- ↑ "Atractosteus spatula :: Florida Museum of Natural History". www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu. Retrieved 2018-05-11.

- ↑ "Lepisosteus oculatus (Spotted gar)". Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 2018-05-11.

- ↑ "Spotted Gar (Lepisosteus oculatus) - Species Profile". nas.er.usgs.gov. Retrieved 2018-05-11.

- ↑ Wiley, Edward G. (1998). Paxton, J.R.; Eschmeyer, W.N., eds. Encyclopedia of Fishes. San Diego: Academic Press. pp. 78–79. ISBN 0-12-547665-5.

- ↑ Renfro, Larry; Hill, Loren (1970). "Factors Influencing the Aerial Breathing and Metabolism of Gars (Lepisosteus)". The Southwestern Naturalist. 15 (1): 45–54. JSTOR 3670201.

- ↑ Hill, Loren (1972). "Social Aspects of Aerial Respiration of Young Gars (Lepisosteus)". The Southwestern Naturalist. 16 (3): 239–247. JSTOR 3670060.

- ↑ Becker, George (1983). "Fishes of Wisconsin" (PDF): 239–248.

- ↑ Malcolm, Jollie. "Development of Cranial and Pectoral Girdle Bones of Lepisosteus with a Note on Scales". Copeia. American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists (ASIH). JSTOR 1445204.

- ↑ "Alligator Gar (Atractosteus spatula)". Texas Parks & Wildlife Department. Retrieved March 8, 2016.

- 1 2 3 Kodera H. et al.: Jurassic Fishes. TFH, 1994, ISBN 0-7938-0086-2

- ↑ Monks N. (editor): Brackish Water Fishes, pp 322–324. TFH 2006, ISBN 0-7938-0564-3

- ↑ Jeremy J. Wright, Solomon R. David, Thomas J. Near: Gene trees, species trees, and morphology converge on a similar phylogeny of living gars (Actinopterygii: Holostei: Lepisosteidae), an ancient clade of ray-finned fishes. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 63 (2012) 848–856 PDF

- ↑ Cavin, Lionel; Martin, Michel; Valentin, Xavier (1996). "Occurrence of Atractosteus africanus (actinopterygii, lepisosteidae) in the early Campanien of Ventabren (Bouches-du-Rhône, France). Paleobiogeographical implications". Revue de Paléobiologie. 15 (1): 1–7.

- ↑ "Gar". Environment.nationalgeographic.com. Retrieved 29 May 2011.

- 1 2 Ostrand, Kenneth G.; Thies, Monte L.; Hall, Darrell D.; Carpenter, Mark (1996). "Gar ichthyootoxin: Its effect on natural predators and the toxin's evolutionary function". The Southwestern Naturalist. 41 (4): 375–377. JSTOR 30055193.

- ↑ Fuhrman, Frederick A.; Fuhrman, Geraldine J.; Dull, David L.; Mosher, Harry S. (1969-05-01). "Toxins from eggs of fishes and amphibia". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 17 (3): 417–424. doi:10.1021/jf60163a043. ISSN 0021-8561.

- ↑ Burton, Maurice; Robert Burton (2002). The international wildlife encyclopedia, Volume 9. Marshall Cavendish. p. 929. ISBN 978-0-7614-7266-7. Retrieved 18 July 2010.

- ↑ Spitzer, Mark (2010). Season of the Gar: Adventures in Pursuit of America's Most Misunderstood Fish. U of Arkansas P. pp. 118–19. ISBN 978-1-55728-929-2.