Lauda Air Flight 004

.jpg) OE-LAV, the plane involved in the crash. | |

| Accident | |

|---|---|

| Date | 26 May 1991 |

| Summary | In-flight break-up caused by uncommanded thrust reverser deployment |

| Site |

Phu Toei National Park, Amphoe Dan Chang, Suphanburi Province, Thailand |

| Aircraft | |

| Aircraft type | Boeing 767-3Z9ER |

| Aircraft name | Mozart |

| Operator | Lauda Air |

| Registration | OE-LAV |

| Flight origin | Kai Tak Airport, British Hong Kong |

| Stopover |

Don Mueang International Airport, Bangkok, Thailand |

| Destination |

Vienna International Airport, Vienna, Austria |

| Passengers | 213 |

| Crew | 10 |

| Fatalities | 223 |

| Survivors | 0 |

Lauda Air Flight 004 was a regularly scheduled international passenger flight between Bangkok, Thailand, and Vienna, Austria. On 26 May 1991, the thrust reverser on the No.1 engine of the Boeing 767-300ER operating the flight deployed in flight without being commanded, causing the aircraft to spiral out of control, break up, and crash, killing all 213 passengers and the 10 crew members on board. It was the 767's first fatal incident and third hull loss. Lauda Air was founded and run by the former Formula One world motor racing champion Niki Lauda. Lauda was personally involved in the accident investigation.

Aircraft

The aircraft involved was a Boeing 767-300ER that was powered by Pratt & Whitney PW4060 engines and delivered new to Lauda Air on 16 October 1989.[1] The aircraft was registered OE-LAV and was christened Mozart.[2]

History of the flight

At the time of the accident, Lauda Air operated three weekly flights between Bangkok and Vienna.[3] On 26 May 1991, at 23:02 local time, flight NG004 (originating from Hong Kong's Kai Tak Airport), a Boeing 767-3Z9ER, took off from Don Mueang International Airport for its flight to Vienna International Airport with 213 passengers and ten crew, under the command of Captain Thomas J. Welch of the United States and First Officer Josef Thurner of Austria.

At 23:08, Welch and Thurner received a visual warning indicating that a possible system failure would cause the thrust reverser on the number one engine to deploy in flight. Having consulted the aircraft's quick reference handbook, they determined that it was "just an advisory thing" and took no action.[4]

At 23:17, the number one engine reversed thrust while the plane was over mountainous jungle terrain in the border area between Suphanburi and Uthai Thani provinces in Thailand. Thurner's last recorded words were, "Oh, reverser's deployed".[5][6] The lift on the aircraft's left side was disrupted due to the reverser deployment, and the aircraft was placed in an immediate diving left turn. The aircraft went into a diving speed of Mach 0.99, and may have broken the sound barrier. The aircraft broke up in mid-air at 4,000 feet (1,200 m).[7] Most of the wreckage was scattered over a remote forest area roughly 1 km2 in size, at an elevation of 600 m (2,000 ft) above sea level, in what is now Phu Toei National Park, Suphanburi. The wreckage site is about 6 kilometres (3 nmi) north-northeast of Phu Toey, Huay Kamin, Dan Chang District, Suphan Buri Province,[8] about 160 kilometres (100 mi) northwest of Bangkok, close to the Burma-Thailand border.[3][9] Rescuers found Welch's body still in the pilot's seat.[10]

Recovery

Volunteer rescue teams and local villagers looted the wreckage, taking electronics and jewellery,[11] so relatives were unable to recover personal possessions. The bodies were taken to a hospital in Bangkok. The storage was not refrigerated and the bodies decomposed. Dental and forensic experts worked to identify bodies, but twenty-seven were never identified.[12]

Speculation

Speculation circulated that a bomb may have destroyed the aircraft. The Philadelphia Inquirer, citing wire services it did not identify, stated that "the search for a motive is difficult because politically neutral Austria has generally stayed out of most international conflicts – such as the Persian Gulf war – that have made other countries' airlines the targets of terrorist attacks."[13]

Investigation

The flight data recorder was completely destroyed, so only the cockpit voice recorder was of use. Pradit Hoprasatsuk, the head of the Air Safety Division of the Thailand Department of Aviation, stated, "the attempt to determine why the reverser came on was hampered by the loss of the flight data recorder, which was destroyed in the crash".[14] Upon hearing of the crash, Niki Lauda traveled to Thailand. He examined the wreckage and estimated that the largest fragment was about 5 metres (16 ft) by 2 metres (6.6 ft), which was about half the size of the largest piece in the Lockerbie crash.[15] In Thailand, Lauda attended a funeral for 23 unidentified passengers, and then traveled to Seattle to meet with Boeing representatives.

The official investigation took about eight months.[16] It did not determine the cause of the thrust reverser deployment. Different possibilities were investigated, including a short circuit in the system. Due in part to the destruction of much of the wiring, no definitive reason for the activation of the thrust reverser could be found.[8]

As evidence started to point towards the thrust reversers as the cause of the accident, Lauda made simulator flights at Gatwick Airport which appeared to show that deployment of a thrust reverser was a survivable incident. Lauda said that the thrust reverser could not be the sole cause of the crash.[17] However the accident report states that the "flightcrew training simulators yielded erroneous results"[2] and stated that recovery from the loss of lift from the reverser deployment "was uncontrollable for an unexpecting flight crew".[18] The incident led Boeing to modify the thrust reverser system to prevent similar occurrences by adding sync-locks, which prevent the thrust reversers from deploying when the main landing gear truck tilt angle is not at the ground position.[8][19]

The aviation writer Macarthur Job has said that "had that Boeing 767 been of an earlier version of the type, fitted with engines that were controlled mechanically rather than electronically, then that accident could not have happened".[5]

Niki Lauda's visit with Boeing

Lauda stated, "what really annoyed me was Boeing's reaction once the cause was clear. Boeing did not want to say anything."[16] Lauda asked Boeing to fly the scenario in a simulator that used different data as compared to the one that Lauda had performed tests on at Gatwick airport.[20] Boeing initially refused, but Lauda insisted. Lauda attempted the flight in the simulator 15 times, and in every instance he was unable to recover. He asked Boeing to issue a statement, but the legal department said it could not be issued because it would take three months to adjust the wording. Lauda asked for a press conference the following day, and told Boeing that if it was possible to recover, he would be willing to fly on a 767 with two pilots and have the thrust reverser deploy in air. Boeing told Lauda that it was not possible, so he asked Boeing to issue a statement saying that it would not be survivable, and Boeing issued it. Lauda then added, "this was the first time in eight months that it had been made clear that the manufacturer [Boeing] was at fault and not the operator of the aeroplane [or Pratt and Whitney]."[16]

Previous testing of thrust reversers

When the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) of the United States asked Boeing to do tests activating the thrust reverser in flight,[21] the FAA had allowed Boeing to establish the tests of the thrust reverser. Boeing had insisted that a deployment was not possible in flight. In 1982 Boeing established a test where the aircraft was slowed to 250 knots, and the test pilots then used the thrust reverser. The control of the aircraft had not been jeopardized. The FAA accepted the results of the test.[22]

The Lauda aircraft was traveling at a high speed when the thrust reversers deployed, causing the pilots to lose control of the aircraft. James R. Chiles, author of Inviting Disaster, said, "the point here is not that a thorough test would have told the pilots Thomas J. Welch and Josef Thumer [sic] what to do. A thrust reverser deploying in flight might not have been survivable, anyway. But a thorough test would have informed the FAA and Boeing that thrust reversers deploying in midair was such a dangerous occurrence that Boeing needed to install a positive lock that would prevent such an event." As a result of their findings during the investigation process of Lauda Flight 004, additional safety features such as mechanical positive locks were mandated to prevent thrust reverser deployment in flight.[23]

Passengers and crew

| Nationality | Passengers | Crew | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 74 | 9 | 83 | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 6 | 0 | 6 | |

| 4 | 0 | 4 | |

| 52 | 0 | 52 | |

| 2 | 0 | 2 | |

| 10 | 0 | 10 | |

| 2 | 0 | 2 | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 3 | 0 | 3 | |

| 7 | 0 | 7 | |

| 3 | 0 | 3 | |

| 39 | 0 | 39 | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 2 | 0 | 2 | |

| 2 | 1 | 3 | |

| 3 | 0 | 3 | |

| Total | 213 | 10 | 223 |

The passengers and crew included 83 Austrians:[24] 74 Austrian passengers and nine Austrian crew members.[25] 52 Hong Kong residents were on board the aircraft.[25][26] Other nationalities included Thais (39), Italians (10), Swiss (7), Chinese (6), Germans (4), Portuguese (3), Taiwanese (3), Yugoslavs (3), Hungarians (2), Filipinos (2), Britons (2), Americans (2), Australian (1), Brazilian (1), Polish (1), and Turkish (1).[25] In addition, an American was the aircraft's pilot.[27]

Of the passengers, 125 had boarded in Hong Kong, while the rest boarded in Bangkok.[24] Of the passengers who boarded in Bangkok, there were 38 Thais, 34 Austrians, seven Swiss, four Germans, two Yugoslavs, one Australian, one Briton, and one Hungarian.[3] Of the passengers who boarded in Hong Kong, most were either Austrian or Chinese.[9]

Of the passengers, 10 were from South Tyrol in Italy. Six of them were students of the University of Innsbruck School of Economics, and they originated from Val Gardena (Gröden), Kiens (Chienes), Klausen (Chiusa), Mals (Malles Venosta), and Olang (Valdaora). The other four were from Bolzano (Bozen), including two public officers, a musician, and his daughter. The musician was traveling with his Chinese wife.[28]

Notable victims

- Pairat Decharin, the Governor of Chiang Mai Province, and his wife.[10][29] Charles S. Ahlgren, the former U.S. consul general to Chiang Mai, said "That accident not only took their lives and that of many of Chiang Mai's leaders, but dealt a blow to many development and planning activities in the town."[30]

- Clemens August Andreae, an Austrian economics professor,[31] was leading a group of students from the University of Innsbruck on a tour of the Far East.[28]

Josef Thurner, the copilot, once flew as a copilot with Niki Lauda on a Lauda Boeing 737 service to Bangkok, a flight that was the subject of a Reader's Digest article in January 1990 that depicted the airline positively. Macarthur Job said that, as a result, Thurner was the better known of the crew members.[32] Thomas J. Welch, the captain, lived in Vienna,[25] but originated from Seattle, Washington.[27]

Aftermath

About one quarter of the airline's carrying capacity was destroyed as a result of the crash.[33] Following the crash of OE-LAV, the airline had no flights to Sydney, on 1, 6, and 7 June. Flights resumed with another 767 on 13 June.[34] Niki Lauda said that the crash in 1991 and the period after was the worst time in his life.[16] After the crash, bookings from Hong Kong decreased by 20% but additional passengers from Vienna began booking flights, so there were no significant changes in overall bookings.[26]

In early August 1991, Boeing issued an alert to airlines stating that over 1,600 late model 737s, 747s, 757s, and 767s had thrust reverser systems similar to that of OE-LAV. Two months later, customers were asked to replace potentially faulty valves in the thrust reverser systems that could cause reversers to deploy in flight.[35]

At the crash site, which is accessible to national park visitors, a shrine was later erected to commemorate the victims.[36] Another memorial and cemetery is located at Wat Sa Kaeo Srisanpetch – GPS location: 14°29′30″N 100°00′08″E / 14.4918°N 100.0022°E, some 90 km away in Amphoe Mueang Suphanburi.[37]

Television episodes

- Mayday discussed Lauda Air Flight 004 in its fourteenth season on 12 January 2015 titled "Niki Lauda: Testing the Limits".

- Modernine TV discussed Lauda Air Flight 004 in the Time Line 1st episode on 23 March 2015 titled "Lauda : Tragic Night Sky".[38]

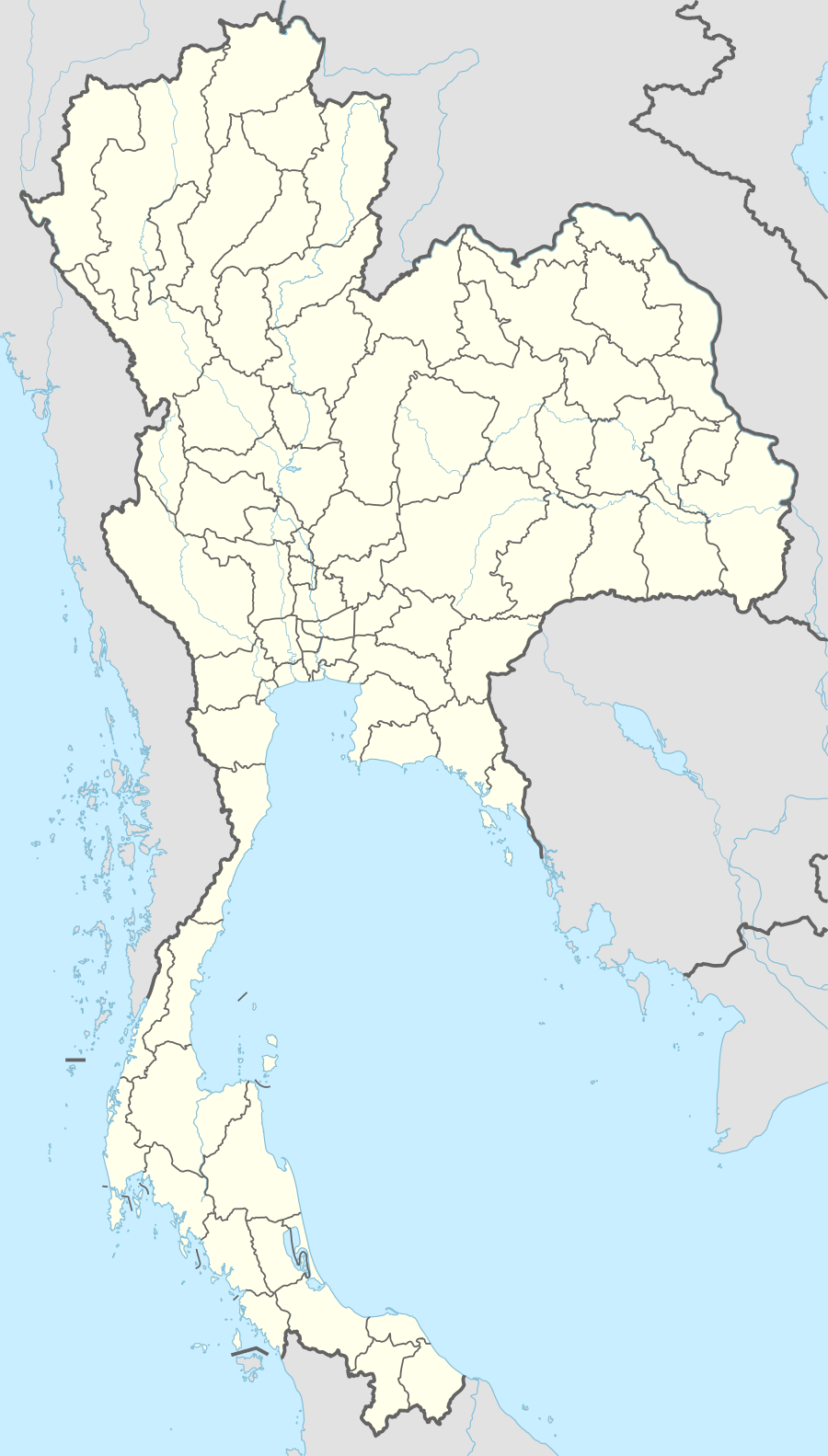

Maps

Hong Kong Bangkok Crash site Vienna Location of departure, stopover, crash site and destination |

Don Mueang Airport Crash site Location of stopover and crash site |

See also

Notes

- ↑ airfleets.net – Boeing 767 – MSN 24628 – OE-LAV retrieved 3 July 2016

- 1 2 "Accident Report, section 2.3, page 21". Rvs.uni-bielefeld.de. Archived from the original on 27 May 2011. Retrieved 14 February 2014.

- 1 2 3 Tummachartvijit, Tavorn. "Cause of airliner explosion Sought". Associated Press at The Dispatch. Monday 27 May 1991. 1A and 6A.

- ↑ Accident description at the Aviation Safety Network

- 1 2 Job, Macarthur (1996). Air Disaster Volume 2, Aerospace Publications, ISBN 1-875671-19-6: pp.203–217

- ↑ "Accident Report, Appendix A, page 55". Rvs.uni-bielefeld.de. Archived from the original on 27 May 2011. Retrieved 14 February 2014.

- ↑ Chiles, p. 309.

- 1 2 3 "Accident Report". Rvs.uni-bielefeld.de. Archived from the original on 27 May 2011. Retrieved 14 February 2014.

- 1 2 "More Than 200 Believed Killed As Plane Crashes in Thai Jungle". Associated Press. 27 May 1991. Retrieved on 27 January 2013.

- 1 2 "UN drug man 'not Thai bomb target'". The Independent. Thursday 30 May 1991. Available on LexisNexis.

- ↑ Johnson, Sharen Shaw. "Scavengers complicate crash probe". USA Today. 29 May 1991. News 4A.

- ↑ Finlay, Victoria. "Relatives return to crash site for memorial service". South China Morning Post. Tuesday 25 May 1993. Retrieved on 26 May 2013.

- ↑ "Looting May Hurt Jet-crash Probe; Airline Chief Denies Extortion Plot". Inquirer Wire Services at The Philadelphia Inquirer. 1. Retrieved on 26 May 2013.

- ↑ Archive. Associated Press. 31 August 1993. Retrieved on 16 March 2014.

- ↑ "Looting may have hidden clues to crash". The Advertiser. Thursday 30 May 1991.

- 1 2 3 4 Lauda, Niki (interview by Maurice Hamilton). "Niki Lauda: 'People had lost their loved ones yet no one was telling them why'". Observer Sport Monthly at The Guardian. 29 October 2006. Retrieved on 15 February 2013.

- ↑ "Rejects Thrust as Cause of Air Crash". The New York Times. 7 June 1991. Retrieved on 26 January 2013.

- ↑ "Accident Report, section 3.1, 9, page 41". Rvs.uni-bielefeld.de. Archived from the original on 27 May 2011. Retrieved 14 February 2014.

- ↑ Acohido, Byron. "Boeing Thrust Reversers Had History Of Glitches". Chicago Tribune.

- ↑ Hank Williamson (2011). Air Crash Investigations: Suddenly Falling Apart The Crash Of Lauda Air Flight NG 004, ISBN 978-1257505401: p.40

- ↑ Chiles, p. 112-113

- ↑ Chiles, p. 113

- ↑ Chiles, p. 114.

- 1 2 Traynor, Irian, Nick Cumming-Bruce, and Steve Vines. "Crash teams investigate plane blast". The Independent. 28 May 1991. Available on LexisNexis.

- 1 2 3 4 Wallace, Charles P. "'All Evidence' in Thai Air Crash Points to Bomb". Los Angeles Times. 28 May 1991. 2. Retrieved on 15 February 2013.

- 1 2 Finlay, Victoria. "Jet tragedy families wait on pay". South China Morning Post. Tuesday 25 May 1993. Retrieved on 27 January 2013.

- 1 2 "Pilots' Final Words". Associated Press at The Seattle Times. Thursday 6 June 1991. Retrieved on 15 February 2013.

- 1 2 Parschalk and Thaler, p. 394 "Sechs der zehn Südtiroler Opfer sind Studenten der Innsbrucker Fakultät für Wirtschaftswissenschaften aus Klausen, Gröden, Olang, Mals und Kiens, die unter der Leitung von Clemens August Andreae an einer Exkursion nach Fernost teilgenommen hatten. Die anderen vier Südtiroler Todesopfer – alle aus Bozen – sind zwei Beamte sowie ein Berufsmusiker mit seiner chinesischen Frau und dem in Bozen geborenen Töchterchen der beiden."

- ↑ "รายนามผู้ดำรงตำแหน่งผู้ว่าราชการจังหวัดเชียงใหม่". chiangmai.go.th (in Thai). Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- ↑ "Special Messages from 8 U.S. Consuls General in Chiang Mai". (Archive) Department of State. Retrieved on 15 February 2013. Thai version, Archive

- ↑ "Lauda Air-Absturz in Thailand jährt sich zum 20. Mal." Die Presse. 26 May 2011. Retrieved on 14 February 2013. "Das Unglück 1991 in Thailand war das dritte schwere, von dem ein österreichisches Verkehrsflugzeug betroffen war. Am 26. September 1960 hatte der Absturz einer "Vickers-Viscount"-Turboprop-Maschine der AUA beim Landeanflug auf den Moskauer Flughafen Scheremetjewo 31 Tote gefordert. Schuld war damals eine falsche Höhenmesser-Einstellung. Am 23. September 1989 war eine mit elf Personen besetzte "Commander AC 90" der Rheintal-Flug beim Landeanflug auf den Flughafen Altenrhein am schweizerischen Ufer des Bodensees bei dichtem Nebel in das Gewässer gestürzt. Dabei kam auch der damalige Sozialminister Alfred Dallinger (S) ums Leben." and "In Thailand starb der Innsbrucker Wirtschaftswissenschafter Univ.-Prof. Clemens August Andreae."

- ↑ Job, p. 204. "Of all the crew, Josef Thurner was perhaps the better known thanks to having been copilot to Niki Lauda himself on a Boeing 737 service to Bangkok which became the subject of a highly affirmative article on the airline and its history in the January 1990 issue of The Reader's Digest[...]"

- ↑ Traynor, Ian. "Lauda's driving ambition brings triumph and disaster in tandem". The Independent. 28 May 1991.

- ↑ Aircraft, Volume 71. p. 44. "LAUDA AIR/LDA: Following the still unexplained loss of B767-329ER OE-LAV [24628] Mozart, there were no flights to Sydney by the Austrian carrier on 1, 6 and 7 June. Services resumed on 13 June with B767-3T9 (ER) OE-LAU [23765 xN6009F]

- ↑ Lane, Polly and Byron Acohido. "Boeing Tells 757 Owners To Replace Part – Faulty Thrust-Reverser Valve Blamed In 767 Accident That Killed 223". Seattle Times. Monday, 9 September 1991. Retrieved on 15 February 2013.

- ↑ Paknam Web – Phu Toei National Park Archived 8 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Paknam Web – Lauda Air Cemetery

- ↑ ข่าวดังข้ามเวลา : เลาด้า...คืนฟ้าโศก (23 มี.ค.58)

References

- Accident Report – Lauda Air Flight 004 (Archive) – Aircraft Accident Investigation Committee, Ministry of Transport and Communications Thailand, Prepared for World Wide Web usage by Hiroshi Sogame (十亀 洋 Sogame Hiroshi), a member of the Safety Promotion Committee (総合安全推進 Sōgō Anzen Suishin) of All Nippon Airways

- Aircraft, Volume 71. Royal Aeronautical Society Australian Division, 1991.

- Chiles, James R. Inviting Disaster. HarperCollins, 8 July 2008. ISBN 0061734586, 9780061734588.

- Job, Macarthur. Air Disaster, Volume 2. Aerospace Publications, 1996. ISBN 1875671196, 9781875671199.

- Parschalk, Norbert and Bernhard Thaler. Südtirol Chronik: das 20. Jahrhundert. Athesia, 1999.

Further reading

- Gilbert, Andy. "Lauda Air". South China Morning Post. Thursday 26 May 1994.

- Aviation Week & Space Technology. 3 June 1991 (32), 10.06.91 (28–30)

External links

- Lauda Air Crash 1991: still too many open questions – Austrian Wings – Austrias Aviation Magazine

- "การสอบสวนอากาศยานประสบอุบัติเหต" Department of Civil Aviation (in Thai) (Archive)

- "Computer-Related Incidents with Commercial Aircraft The Lauda Air B767 Accident". (Archive) University of Bielefeld. 26 May 1991.

- Lauda Air Flight 004 (Index of articles) – South China Morning Post

- "flugzeugabsturz_20jahre.pdf" (Archive) University of Innsbruck. – Includes list of University of Innsbruck professors, assistants, and students who died on Flight 004

- Last flight of the Mozart (Der Todesflug der Mozart, German) – Austrian Wings – Austrias Aviation Magazine

- PlaneCrashInfo.Com – Lauda Air Flight 004

- Cockpit Voice Recorder transcript and accident summary

- Grand Prix History – Biography on Niki Lauda (Contains information about Flight 004)