Latch (breastfeeding)

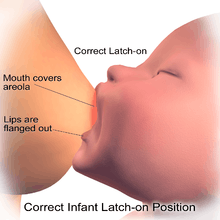

Latch refers to how the baby fastens onto the breast while breastfeeding. How the baby latches is more important than how the baby is held during nursing. A good latch means that the bottom of the areola (the area around the nipple) is in the baby's mouth and the nipple is back inside his or her mouth, where it's soft and flexible. A shallow, or poor, latch happens when the baby does not have enough of the breast in his/her mouth or is too close to the tip. A shallow latch causes the sensitive nipple skin to press against the bones in the top of the baby's mouth. That can cause the development of cracked nipples. The nipples are sore, and bleed.[1]

Positioning

Assuming a comfortable position helps the baby to latch properly.[1][2] It takes practice to get a good latch. The best nursing hold that works best for mother and baby is sometimes discovered through trial and error.[1]

Getting a good latch for breasting can be learned. Recommendations for nursing mothers is to:

- Look for the baby's belly button. If the belly button is visible while the baby is latched, the baby's not comfortable enough to latch well.

- Look around. If the nursing mother can can chat and use her hands without concentrating on holding her position, that's a good position for a latch.

- Check the nipples. The sensitivity of the skin on the nipples and breasts helps the mother's breasts respond to the baby and helps the mother know how much milk to make. When the baby is latched correctly, the bottom part of the areola is also in his or her mouth. But a shallow latch, even if it doesn't hurt right away, will start to hurt soon. A poorly latched baby has to work harder to get the milk out.[1]

Latching on is facilitated by secretions from the nipple that are reported to help align the infants' head with the mother's breast and thought to promote latching and sucking.[3]

Pain

Pain or pinching is a good indication of a poor latch.[1] If the pain lasts longer than a few seconds, the latch is probably too shallow. The technique for getting a good latch is to gently break the suction by placing a clean finger into the baby's mouth and help the baby latch on again. It is normal for the nipple to look slightly elongated or drawn-out.

When the baby latches, it can feel like a pinch that goes away. If it's more painful than that, it's probably a bad latch. A bad, uncorrected latch damage the nipple and compromise milk flow for the baby. [4]

Tongue-tied

Sometimes, a baby's tongue is stuck to the bottom of the mouth by a band of tissue, which means the baby can't open his or her mouth wide enough to get a good latch. Checking for tongue-tie isn't a standard newborn test. If the baby isn't latching on well and doesn't seem to be gaining weight mothers are advised to contact the pediatrician or nurse to ask about this. Fortunately, it's a very simple fix. Once tongue-tie is treated by a medical professional, breastfeeding improves.[1]

Infants will naturally move their head while looking and feeling for a breast to feed. There are many ways to start feeding the infant, and the best approach is the one that works for the mother and the infant. The steps below can help with getting the infant to "latch" on to the breast for feeding.

Hold the infant against a bare chest. Dress the infant in only a diaper to ensure skin-to-skin contact. Keep the infant upright, with his or her head directly under the chin. Support the infant's neck and shoulders with one hand and his or her hips with the other hand. The infant may try to move around to find the breast. The infant's head should be slightly tilted back to make nursing and swallowing easier. When his or her head is tilted back and the mouth is open, the tongue will naturally be down in the mouth to allow the breast to go on top of it. At first, allow the breast to hang naturally. The infant may open his or her mouth when the nipple is near his or her mouth. The mother also can gently guide the infant to latch on to the nipple. While the infant is feeding, his or her nostrils may flare to breathe in air. Do not panic—this flaring is normal. The infant can breathe normally while breastfeeding. As the infant tilts backward, support his or her upper back and shoulders with the palm of the hand and gently pull the infant close.[5]

Good latch

A good latch is important for both effective breastfeeding and comfort. Review the following signs to determine whether the infant has a good latch:

- The latch feels comfortable and does not hurt or pinch. How it feels is a more important sign of a good latch than how it looks.

- The infant does not need to turn his or her head while feeding. His or her chest is close to the body.

- Little or no areola (pronounced uh-REE-uh-luh), which is the dark-colored skin on the breast that surrounds the nipple. Depending on the size of the areola and the size of the infant's mouth, it is possible to only see a small amount of areola. If more areola is showing, it should seem that more is above the infant's lip and less is below.

- The infant's mouth will be filled with breast when in the best latch position.

- The infant's tongue is cupped under the breast, although it might not be seen.

- The infant's swallowing can be heard or seen. Because some babies swallow so quietly, the only way of knowing that they are swallowing is when a pause in their breathing is heard.

- The infant's ears "wiggle" slightly.

- The infant's lips turn outward, similar to fish lips, not inward. The infant's bottom lip may not be seen.

- The infant's chin touches the breast.[5]

Poor latching

Not only is a poor latch painful but it can also lead to blocked milk ducts, mastitis, and other infections. A poor latch also is not good for the baby, as it means he or she isn't getting enough milk. So if poor latching has been occurring for more than a few days breastfeeding mothers can get help. There are resources available at no or low cost.[4]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Breastfeeding checklist: How to get a good latch". WomensHealth.gov. Archived from the original on 4 August 2017. Retrieved 4 August 2017.

- ↑ Henry 2016, p. 120.

- ↑ Doucet, S; Soussignan, R; Sagot, P; Schaal, B (2009). "The secretion of areolar (Montgomery's) glands from lactating women elicits selective, unconditional responses in neonates". PLoS ONE. 4 (10): e7579. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0007579. PMC 2761488. PMID 19851461.

- 1 2 "Common questions about breastfeeding and pain". womenshealth.gov. Archived from the original on 4 August 2017. Retrieved 4 August 2017.

- 1 2 "How Do I Breastfeed?". MedlinePlus. US National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 4 August 2017. Retrieved 4 August 2017.

Bibliography

- Henry, Norma (2016). RN maternal newborn nursing : review module. Stilwell, KS: Assessment Technologies Institute. ISBN 9781565335691.