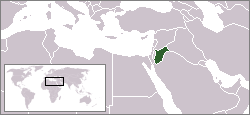

LGBT rights in Jordan

| LGBT rights in Jordan | |

|---|---|

| |

| Same-sex sexual intercourse legal status | Legal since 1951 |

| Gender identity/expression | – |

| Discrimination protections | None |

| Family rights | |

| Recognition of relationships | No recognition of same-sex couples |

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights in Jordan are considered to be relatively advanced, compared to most other countries in the Middle East.

Same-sex sexual activity was illegal in Jordan under the British Mandate Criminal Code Ordinance until 1951, when Jordan adopted its own penal code that did not criminalize homosexuality. Jordan is one of few Muslim countries to do so. However, LGBT people displaying public affection can be prosecuted for "disrupting public morality". A general interest gay magazine is published in Jordan. However, most LGBT persons face social discrimination not experienced by non-LGBT residents.[1]

Criminal laws

The British Mandate Criminal Code Ordinance criminalized homosexuality with up to 10 years in prison, until 1951 when Jordan adopted its own penal code that did not criminalize homosexuality.[2] In 1951, a revision of the Jordanian Criminal Code legalized private, adult, non-commercial, and consensual sodomy, with the age of consent set at 16.[3]

The Jordanian penal code no longer permits family members to beat or kill a member of their own family whose "illicit" sexuality is interpreted as bringing "dishonor" to the entire family.[4] As of 2013, the newly revised Penal Code makes honor killings, as a legal justification for murder, illegal.[5]

The Jordanian penal code gives the police discretion when it comes to protecting the public peace, which has sometimes been used against gay people organizing social events .

LGBT recognition and rights

History

The first time that the Jordanian government made any public statement regarding LGBT rights was at the Fourth World Conference on Women held in 1995. The international conference sought to address women's rights issues on a global scale, and a proposal was made to have the conference formally address the human rights of gay and bisexual women. The Jordanian delegates to the conference helped to defeat the proposal.[6] More recently, the kingdom's United Nations delegates have also opposed efforts to have the United Nations itself support LGBT rights, although this later proposal was eventually adopted by the United Nations.

The Jordanian government also tolerates a few cafes in Amman that are widely considered to be gay friendly.[7]

Books@Cafe opened up in 1997 and remains a popular bookstore and cafe for patrons supportive of "creativity, diversity and tolerance". In the twenty-first century, a Jordanian male model, Khalid, publicly came out and has been supportive of a general interest, gay-themed magazine published in Jordan. "Growing up, it was hard for me to find topics, subjects and publications that I could relate to! In my country, most magazines rejected me and my ideas due to my young age at the time, and I felt like an outcast in my own society!" Khalid told soginews.com.[8]

Recent reports suggest that although a large number of LGBT citizens are in the closet and often have to lead double lives, a new wave of younger LGBT people are beginning to come out of the closet and are becoming more visible in the country, working to establish a vibrant LGBT community of filmmakers, journalists, writers, artists and other young professionals.[9] Only a few young Jordanians of the upper class are able to remain single. Most of these more "open" Jordanians are well educated and from prosperous middle class or wealthy families.

Initial research into the LGBT community in Jordan suggests that many of the same sort of social biases and conventions that exist within the gay community in the United States or Europe, also exist in Jordan.

Recent developments

In 2015, the Jordanian Ministry of Interior issue a statement about LGBT rights in response to publicity surrounding an event in Amman. The statement said that LGBT rights conflicts with Islam, which the Constitution stipulates is the official religion, that Jordanian law criminalize holding public meetings without prior approval and as well as public conduct that breaches the peace or the decorum of society. This statement was in response to publicity surrounding LGBT rights event that was held in Amman. A rough translation of the statement is as follows; " The first clause: The Jordanian state is keen on respecting the Islamic dogma and the true islamic religion's doctrine which was clearly affirmed in the first article of the Jordanian Constitution that states: "Islam is the religion of the Jordanian State" and the provisions of the Jordanian civil law are in line with the provisions of the Islamic Sharia law, jurisprudence and customs as they are the source of legislation; therefore, recognizing LGBT groups is considered as a breach of the Islamic Sharia and subsequently the Jordanian Constitution. Any proposals by the sexually perverted to breach the provisions of Sharia Law and the general order, and for that the aforementioned proposals are considered a crime punishable by law. Second clause: Concerning the IDAHOT meeting; the government did not give its consent for it to be held, knowing that the Law of General Meetings number 7 of year 2004 and its amendments is responsible in organizing any public meeting and so the administrative governor should be informed about the meeting should it be held, which did not happen. Third clause: The Government does not possess any assuring intelligence for the existence of and official sponsorship by a foreign mission including the Embassy of the United States to the aforementioned meeting. Final clause: The government won't tolerate in enforcing the law's provisions to maintain security order and decorum while preserving its Muslim Arab principles and traditions; Therefore, we shall pursue whoever is proven to have breached these principles and submit them to the judiciary to execute the necessary legal action against them."

In 2017, Mashrou’ Leila, a Lebanese-based band, was banned from performing in Jordan. The ban had been issued by the Ministry of Interior, which conflicted with a previous decision by the Jordanian Tourism Board. Conservatives objected to the band's liberal attitudes and the fact that one of the members of the band is gay.

Transgender rights

In 2014, Jordan's Cassation Court, the highest Court in Jordan, allowed a transsexual woman to change her legal name and sex to female after she brought forth medical reports from Australia. The head of the Jordanian Department of Civil Status and Passports stated that two to three cases of change of sex reach the Department annually, all based on medical reports and court orders.[10]

In April 2018, the Jordanian Parliament passed the advanced medical responsibility law that defines "sex change" and "sex reassignment" making the first illegal and punishable with fine and jail time for any doctor who performs what the health committee in the parliament described as "sex change" which is changing the sex of someone who has the chromosomes, genitals and secondary characteristics of one sex.

Media and press

The Media Commission regulates the commercial exhibition and distribution of films and television shows in Jordan. In 2016, the Media Commission ruled that the film The Danish Girl could not be shown publicly because it "encouraged" deviance and public disorder. . Printed media is regulated by the Press and Publication law.

The Press and Publication Law was amended in 1998 and 2004. The initial document prohibited the depiction or endorsement of "sexual perversion", which may have included homosexuality.[11] The revised edition in 2004 has a few provisions of direct impact on LGBT rights. First, the content ban on "sexual perversion" has been replaced with a general requirement that the press "respect the values of ... the Arab and Islamic nation" and that the press must also avoid encroaching into people's private lives.[12]

In 2007, the first gay-themed Jordanian publication My.Kali arose. A year later, My.Kali[13] started publication online, named after openly gay model Khalid Abdel-Hadi, making major headlines, as it is the first LGBT publication to ever exist in the MENA region, with one of the only faces in the pan Arab region.[14][15]

In an article for Al Jazeera English titled 'Pushing for Sexual Equality in Jordan' stated: "Earlier this year, they published the magazine’s 50th issue, and celebrated the magazine’s seven-year anniversary. Kali is on the cover, hugging a sculpture head, his naked torso covered in white dust. The headline reads: “Tell Me Little White Secrets!”" the article was soon removed by the official site, and pasted on blogs and pages instead, due to the huge stir the article caused at the time. "... an AJ foreign journalist wrote a favourable article two years ago on Jordan's only LGBTI magazine My.Kali Magazine but a day later the article was removed from its website and the journalist severely reprimanded." Journalist Dan Littauer writes on his official Facebook page, regarding Qatar's attempts of hushing local medias, and freedom of the press. The magazine regularly features non-LGBT artists on their covers to promote acceptance among other communities and was the first publication to give many underground and regional artists their first covers like Yasmine Hamdan, both lead singer and violinist of band Mashrou' Leila, Hamed Sinno and Haig Papazian, Alaa Wardi,[17] Zahed Sultan[18] and many more. "Jordan is a very traditional country, and we're considered controversial in Jordan for simply breaking the stereotype and stepping out of norm," Khalid told Egypt Independent.[19]

Events were held in the Jordanian capital Amman on the International Day Against Homophobia, Transphobia and Biphobia in 2014 and 2015, mainly for educational purposes and for the purpose of raising voice for the community and discussing challenges. Many activists and members of the LGBT community and LGBT allies in Jordan attended the events. in the second event held in 2015 American ambassador in Jordan Alice Wells was one of the speakers. the event held in 2015 was published in almost all local media outlets.

Public opinion

According to the 2013 survey by the Pew Research Center, 97% of people answers no, 3% answered yes, on question: "Should Society Accept Homosexuality?".[16]

Summary table

| Same-sex sexual activity legal | |

| Equal age of consent | |

| Anti-discrimination laws in employment | |

| Anti-discrimination laws in the provision of goods and services | |

| Anti-discrimination laws in all other areas (incl. indirect discrimination, hate speech) | |

| Same-sex marriages | |

| Recognition of same-sex couples | |

| Step-child adoption by same-sex couples | |

| Joint adoption by same-sex couples | |

| Gays and lesbians allowed to serve openly in the military | |

| Right to change legal gender | |

| Access to IVF for lesbians | |

| Homosexuality declassified as an illness | |

| Commercial surrogacy for gay male couples | |

| MSM allowed to donate blood |

See also

References

- ↑ "Where is it illegal to be gay?". BBC News. Retrieved 23 February 2014.

- ↑ http://old.ilga.org/Statehomophobia/ILGA_SSHR_2014_Eng.pdf

- ↑ Schmitt, Arno & Sofer, Jehoeda, 1992, Sexuality and Eroticism Among Males in Moslem Societies, Binghamton: Harrington Park Press, 1992, ISBN 0-918393-91-4, pages 137-138.

- ↑ "Middle East 'Honour killings' law blocked". BBC News. 8 September 2003. Retrieved 20 January 2011.

- ↑ "Jordan courts sentence 2 for 'honor killings' - World news - Mideast/N. Africa | NBC News". MSNBC. 2007-06-26. Retrieved 2016-07-14.

- ↑ "www.asylumlaw.org" (PDF). www.asylumlaw.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 March 2012. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- ↑ "Jordan LGBT rights". Retrieved 2015-08-27.

- ↑ by miles (27 January 2015). "Innovative LGBTIQ Activist Gives Back to the Community". Sogi News. Archived from the original on 9 March 2015. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- ↑ "Movie Reviews | Three Stories From Amman at The Black Iris of Jordan". Black-iris.com. Retrieved 20 January 2011.

- ↑ https://www.ammonnews.net/article/208487

- ↑ http://www.article19.org/pdfs/press/jordan-draft-press-law.pdf

- ↑ Archived June 14, 2006, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ My.Kali official website

- ↑ "Jordan: a gay magazine gives an hope to Middle East", Ilgrandecolibri.com, retrieved 11 August 2012

- ↑ "Gay Egypy". Gay Middle East. Archived from the original on 11 July 2011. Retrieved 20 January 2011.

- 1 2 "The Global Divide on Homosexuality | Pew Research Center". Pewglobal.org. 2013-06-04. Retrieved 2016-07-14.

- ↑ My.Kali Alaa Wardi cover

- ↑ My.Kali Zahed Sultan cover

- ↑ Egypt Independent: Middle Eastern LGBT magazine looking risky expansion into Arabic