Kelmendi (tribe)

Coordinates: 42°28′N 19°41′E / 42.467°N 19.683°E

Kelmendi (Albanian: Kelmendi) is a northern Albanian tribe and region (Kelmendi mountains, Malet e Kelmendit) in the mountainous borderlands of Albania towards Montenegro, of the wider Malësia-region. Part of the region lies within the Kelmend municipality, and is composed of a Roman Catholic majority and a Muslim minority. The Kelmendi speak a subdialect of Gheg Albanian as in the rest of northern Albania.

Families hailing from Kelmendi can also be found in Plav, Skadarska Krajina (Shestani-Kraja) in Montenegro, and Rugova in Kosovo[a], where they are Muslim. The name is derived from Saint Clement, the patron saint of the region.

Geography

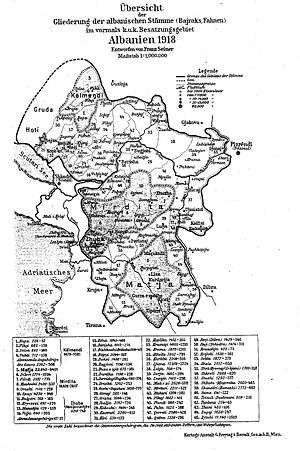

The Kelmendi region is located in the District of Malësi e Madhe in northern Albania, situated in the northernmost and most isolated part of the country. It borders the Albanian tribal regions of Gruda to the west, Hoti to the southwest, Boga to the south, Shala to the east, and the Montenegrin tribal regions of Kuči and Vasojevići to the north.

History

Early history

The Kelmendi are first mentioned in an Ottoman defter (tax registry) of 1497, along with the tribes of Hoti, Kuči and Piperi.[1] They are recorded as having 152 households divided by five small shepherding communities.[1] Robert Elsie thus assumes that they were known as a tribe from the last decades of the 15th century.[1] The defter mentions them as derbendci, mountain-pass keepers, and having tax privileges.[1] The derbendci guarded the Shkodër–Altun-li and Medun–Kuči roads.[1]

As early as 1538, the Kelmendi rose up against the Ottomans.[2] In 1565, the Kelmendi, Kuči and Piperi rose up against the Ottomans.[3] The 1582–83 defter recorded the nahiya of "Klemente" with two villages; the personal names recorded are by majority of Albanian character, minority of Serbian.[4] In the mid-1580s, the Kelmendi seemed to have stopped paying taxes to the Ottomans.[3] They had by this time gradually come to dominate all of northern Albania.[3] They were mobile and went raiding in what is today Kosovo, Bosnia, Serbia and even as far as Plovdiv in Bulgaria.[3]

17th century

Venetian documents from 1609 mention the Kelmendi, Dukagjini, and others having a conflict with the Sultan for 4 years.[5] In April the same year the Dukagjini and others attacked not only the Ottomans, but other northern Albanian tribes who did not support them.[5] The local Ottomans were unable to counter them and were thus forced to ask the Bosnian Pasha for help.[5] Marino Bizzi (1570–1624), the Archbishop of Bar, mentions them in 1610 as "almost all are Catholics, speaking Albanian and Serbian".[b] Bizzi reported an incident in 1613 in which an Ottoman commander, Arslan Pasha, raided the villages of the Kelmendi and started taking prisoners, until an agreement was reached with the Kelmendi clans. According to the agreement, the Kelmendi would surrender fifteen of their members as slaves, and pay a tribute of 1,000 ducats to the Ottomans. However, as Arslan Pasha waited for the payment of the tribute, the Kelmendi ambushed part of his troops and killed about thirty cavalrymen. After this incident the Ottoman troops retreated to Herceg Novi (Castelnuovo).[6] Mariano Bolizza recorded the "Climenti" in his 1614 report as being a Roman rite village, describing them as "an untiring, valorous and extremely rapacious people", with 178 houses, and 650 men in arms commanded by Smail Prentashev and Peda Suka.[7] In 1614, they, along with the tribes of Kuči, Piperi and Bjelopavlići, sent a letter to the kings of Spain and France claiming they were independent from Ottoman rule and did not pay tribute to the empire.[8][9] Clashes with the Ottomans continued through the 1630 and culminate in 1637-38 where the tribe would repel an army of 12,000 (according to some sources 30,000) commanded by Vutsi Pasha of the Bosnia Eyalet. Ottoman casualties vary from 4,000 to 6,000, based on different sources. The legend of Nora of Kelmendi would come to life during this epic struggles.[10]

In the Cretan War the Kelmendi played a tactical role between the Ottomans and the Venetians. In 1664, Evliya Celebi mentioned Kelmendi Albanians among the "infidel warriors" he saw manning Venetian ships in the harbour of Split. The Kelmendi promised support to whichever side would fulfil their requests. in 1666, for instance some of the Kelmendi supported the Ottomans on condition that they be exempted from paying tribute for five years. Some of them also converted to Islam.[11]

In 1651, they aided the army of Ali-paša Čengić, which attacked Kotor; the army raided and destroyed many monasteries in the region.[12] In 1658, the seven tribes of Kuči, Vasojevići, Bratonožići, Piperi, Klimenti, Hoti and Gruda allied themselves with the Republic of Venice, establishing the so-called "Seven-fold barjak" or "alaj-barjak", against the Ottomans.[13]

In 1685, Süleyman, sanjak-bey of Scutari, annihilated the bands of Bajo Pivljanin that supported Venice at the Battle on Vrtijeljka.[14] Süleyman was said to have been aided by the Brđani (including the Klimenti[12]), who were in feud with the Montenegrin tribes.[15] The Klimenti lived off of plundering. Plav, Gusinje, and the Orthodox population in those regions suffered the most from the Klimenti's attacks.[15] The Klimenti also raided the Peć area, and they were so powerful there that some villages and small towns paid them tribute.[15] In March 1688, Süleyman attacked the Kuči tribe;[16] the Kuči, with help from Klimenti and Piperi, destroyed the army of Süleyman twice, took over Medun and got their hands of large quantities of weapons and equipment.[13] In 1692, Süleyman defeated the Montenegrins at Cetinje, once again with the help of the Brđani.[15]

In 1689 the Kelmendi volunteered in the Imperial Army of the Holy Roman Empire during the Kosovo campaign. Initially they were serving Süleyman, but after negotiations with a Venetian official, they abandoned the Ottoman ranks.[17] In October 1689, Arsenije III Čarnojević allied himself with the Habsburgs, gaining the title of Duke. He met up with Silvio Piccolomini in November, and put under his wings a large army of Serbs, including some Klimenti.[18]

18th century

_7832.NEF_10.jpg)

In 1700, the pasha of Peć, Hudaverdi Mahmut Begolli, resolved to take action against the continuing Kelmendi depredations in western Kosovo. With the help of other mountain tribes, he managed to block the Kelmendi in their homelands, the gorge of the upper Cem river, from three sides and advanced on them with his own army from Gusinje, In 1702, having worn them down by starvation, he forced the majority of them to move to the Pešter plateau. Only the people of Selcë were allowed to stay in their homes. Their chief had converted to Islam, and promised to convert his people to. A toltal of 251 Kelmendi households (1,987 people) were resettled in the Pešter area on that occasion. Other were resettled in Gjilan Kosovo. However five years later the exiled Kelmendi managed to fight their way back to their homeland, and in 1711 they sent out a large raiding force to bring back some other from Pešter too.[19]

In the 18th century, Hoti and Kelmendi assisted the Kuči and Vasojevići in the battles against the Ottomans; after that unsuccessful war, a part of the Klimenti fled their lands.[20] After the defeat in 1737, under Archbishop Arsenije IV Jovanović Šakabenta, a significant number of Serbs and Kelmendis retreated into the north, Habsburg territory.[21] Around 1,600 of them settled in the villages of Nikinci and Hrtkovci, where they later adopted a Croat identity.[22]

Late modern period

During the Albanian revolt of 1911 on 23 June Albanian tribesmen and other revolutionaries gathered in Montenegro and drafted the Greçë Memorandum demanding Albanian sociopolitical and linguistic rights with three of the signatories being from Kelmendi.[23] In later negotiations with the Ottomans, an amnesty was granted to the tribesmen with promises by the government to build one to two primary schools in the nahiye of Kelmendi and pay the wages of teachers allocated to them.[23]

On May 26, 1913, 130 leaders of Gruda, Hoti, Kelmendi, Kastrati and Shkreli sent a petition to Cecil Burney in Shkodër against the incorporation of their territories into Montenegro.[24] Franz Baron Nopcsa, in 1920, puts the Klimenti as the first of the Albanian clans, as the most frequently mentioned of all.[25]

Contemporary history

By the end of the Second World War, the Albanian Communists sent its army to northern Albania to destroy their rivals, the nationalist forces. The communist forces met open resistance in Nikaj-Mertur, Dukagjin and Kelmend, which were anti-communist. Kelmend was headed by Prek Cali. On January 15, 1945, a battle between the Albanian 1st Brigade and nationalist forces was fought at the Tamara Bridge. Communist forces lost 52 soldiers, while in their retaliation about 150 people in Kelmend people were brutally killed.[26] Their leader Prek Cali was executed.

This event was the starting point of other dramas, which took place during Enver Hoxha's dictatorship. Class struggle was strictly applied, human freedom and human rights were denied, Kelmend was isolated both by the border and by lack of roads for other 20 years, agricultural cooperative brought about economic backwardness, life became a physical blowing action etc. Many Kelmendi people fled, some others froze by bullets and ice when trying to pass the border.[27]

Ethnography

Origin

There are various theories on the origin of the Kelmendi. Several anthropologists and historians have recorded various founding myths.

- Johann Georg von Hahn (1811–1869), one of the founders of Albanology, placed the settlement of Kelmendi's first patriarch in Bestana, southern Kelmend. The foundations of the settlements, where the Kelmendi are found in modern times, have been attributed to his seven sons.[28]

- Augustin Theiner (1804–1874), the German historian, said that the Clementini hailed from a Clemente, whose father was a Serb from Moraccia (Morača), and mother was from Cucci (Kuči).[29]

- French consul Hyacinte Hecquard (1814–1866), noted that all of the Kelmendi (Clementi) except the families called Onos believe that they descend from one ancestor, Clemens or Clement (Kelment or Kelmend[30] in Albanian).[31] The Franciscan priest, Gabriel, told the story that Clemens was a Venetian who worked as a priest in Venetian Dalmatia and Herzegovina before taking refuge in Albania.[32] Tradition held that he originated from either of those two provinces, and that he was encountered by a pastor in Triepshi (Tripesci).[32]

- Yugoslav anthropologist Andrija Jovičević recorded several stories about their origin. One story has it that the founder settled from Lajqit e Hotit, in Hoti, and to Hoti from Fundane, the village of Lopare in Kuči; he was upset with the Hoti and Kuči, and therefore left those tribes. When he lived in Lopare, he married a girl from Triepshi, who followed him. His name was Amati, and his wife's name was Bumče. According to others, his name was Klmen, from where the tribe received its name. Another story, which Jovičević had heard in Selce, was that the founder was from Piperi, a poor man that had worked as a servant for a wealthy Kuči, there he sinned with a girl from a noble family, and left via the Cijevna.[33] Milan Šufflay (1879-1931) noted that among some Kelmendi, Nikola "Sharp-minded" Kolmendija (Nikola Oštroumni Kolmendija) was noted as the founding father.[34] Some Serbian historians view that the tribe was of Serb origin,[35][36][37][38] originally adhering to the Orthodox Church, converting to Catholicism, and subsequently Albanianized.[39]

Folklore

During Easter processions in Selcë and Vukël the kore, a child-eating demon, was burnt symbolically.[40] In Christmas time alms were placed upon ancestors' graves. As in other northern Albanian clans the Kanun (customary law) that is applied in Kelmend is that of The Mountains (Albanian: Kanuni i Maleve). According to Franz Baron Nopcsa's researches the Kelmendi were the most numerous and notable of the northern Albanian clans.[30]

Families

Kelmend

The region consists of six primary villages: Boga, Nikç, Selcë, Tamarë, Vermosh and Vukël, all part of the Kelmend municipality. Their tribal neighbours are the Kuči and Hoti, to the west, and the Vasojevići to the north. In the late Ottoman period, the tribe of Kelmendi consisted of 500 Catholic and 50 Muslim households.[41] The following lists are of families in the Kelmend region by village of origin (they may live in more than one village):

|

|

|

Montenegro

- Plav-Gusinje

- Ahmetaj or Ahmetović, in Vusanje. They descend from a certain Ahmet Nikaj, son of Nika Nrrelaj and grandson of Nrrel Balaj, and are originally from Vukël in northern Albania.

- Bacaj

- Balaj (Balić), in Grnčar. Immigrated to Plav-Gusinje in 1698 from the village of Vukël or Selcë in northern Albania and converted to Islam the same year. The clan's closest relatives are the Balidemajt/Balidemići. Legend has it that the Balaj, Balidemaj and Vukel clans descended from three brothers. However, a member of the Vukel clan married a member of the Balić clan, later resulting in severed relations with the Vukel clan.

- Balidemaj (Bal(j)idemaj/Balidemić), in Martinovići. This branch of the clan remained Catholic for three generations, until Martin's great-grandson converted to Islam, taking the name Omer. Since then, the family was known as Omeraj/Omerović. Until recently was the family's name changed to Balidemaj, named after Bali Dema, an army commander in the Battle of Novšiće (1789). The clan's closest relatives are the Balajt/Balići. Legend has it that the Balaj, Balidemaj and Vukel clans descended from three brothers.

- Bruçaj (Bručaj/Bručević), they are descendants of a Catholic Albanian named Bruç Nrrelaj, son of Nrrel Balaj, and are originally from Vukël in northern Albania.

- Cakaj (Cakić)

- Canaj (Canović), in the villages of Bogajići, Višnjevo and Đurička Rijeka. Immigrated to Plav-Gusinje in 1698 from the village of Vukël in northern Albania and converted to Islam the same year.

- Çelaj (Čeljaj/Čelić), in the villages of Vusanje and Vojno Selo. Claims descendance from Nrrel Balaj. The Nikça/Nikča family are part of the Çelaj.

- Dedushaj (Dedušaj/Dedušević), in Vusanje. They are descendants of a Catholic Albanian named Ded (Dedush) Balaj, son of Nrrel Balaj, and are originally from Vukel in northern Albania.

- Hakaj (Hakanjin), in Hakanje.

- Hasilović, in Bogajiće.

- Goçaj (Gočević), in Vusanje.

- Gjonbalaj (Đonbaljaj/Đonbalić; also Đombal(j)aj/Đombalić), in Vusanje, with relatives in Vojno Selo. Their ancestor, a Catholic Albanian named Gjon Balaj, immigrated with his sons: Bala, Aslan, Tuça and Hasan; along with his brother, Nrrel, and his children: Nika, Ded (Dedush), Stanisha, Bruç and Vuk from the village of Vukël in northern Albania to the village of Vusanje/Vuthaj in the late-17th century. Upon arriving, Gjon and his descendants settled in the village Vusanje/Vuthaj and converted to Islam and were known as the Gjonbalaj. Relatives include Ahmetajt/Ahmetovići, Bruçajt/Bručevići, Çelajt/Čelići, Goçaj/Gočević, Lekajt/Lekovići, Selimajt/Selimovići, Qosajt/Ćosovići, Ulajt/Uljevići, Vuçetajt/Vučetovići.

- Kukaj (Kukić), in Vusanje

- Lecaj (Ljecaj), in Martinovići. They are originally from Vukël in northern Albania.

- Lekaj (Leković), in Gornja Ržanica and Vojno Selo. They are originally from Vukël in northern Albania. They are descendants of a certain Lekë Pretashi Nikaj.

- Martini (Martinović), in Martinovići. The eponymous founder, a Catholic Albanian named Martin, immigrated to the village of Trepča in the late 17th century from Selcë.

- Hasangjekaj (Hasanđekaj/Hasanđekić), in Martinovići. They descend from a Hasan Gjekaj from Vukël, a Muslim of the Martini clan.

- Prelvukaj (Preljvukaj/Preljvukić), in Martinovići. They descend from a Prelë Vuka from Vukël, of the Martini clan.

- Musaj (Musić), Immigrated to Plav-Gusinje in 1698 from village Vukël in northern Albania and converted to Islam the same year.

- Novaj (Novović)

- Pepaj (Pepić), in Pepići

- Rekaj (Reković), in Bogajići, immigrated to Plav-Gusinje circa 1858.

- Rugova (Rugovac), in Višnjevo with relatives in Vojno Selo and Babino Polje. They descend from a Kelmend clan of Rugova in Kosovo.

- Qosaj/Qosja (Ćosaj/Ćosović), in Vusanje. They are descendants of a certain Qosa Stanishaj, son of Stanisha Nrrelaj and are originally from Vukël in northern Albania.

- Selimaj (Selimović),

- Smajić, in Novšići.

- Ulaj (Uljaj/Uljević), in Vusanje. They are originally from Vukël in northern Albania. They are descendants of a certain Ulë Nikaj, son of Nika Nrrelaj.

- Vukel (Vukelj), in Dolja. They immigrated to Gusinje in 1675 from the village of Vukël in northern Albania. A certain bey from the Šabanagić clan gave the clan the village of Doli.

- Vuçetaj (Vučetaj/Vučetović), in Vusanje. They are originally from Vukël in northern Albania. They are descendants of a certain Vuçetë Nikaj, son of Nika Nrrelaj.

The families of Đomboljaj (alb. Gjonbalaj/Gjombalaj), Uljaj (alb. Ulaj), Ahmetaj and Vučetaj (alb. Vuçetaj) had previously the surnames of Đombolić, Uljević, Ahmetović and Vučetović.[42]

- Skadarska Krajina and Šestani

- Dabović, in Gureza, Livari and Gornji Šestani. Can be found in Shkodër. Their relatives are the Lukić clan in Krajina.

- Lukić - Related to the Dabović clan in Krajina.

- Radovići, in Zagonje.

- Elsewhere

The families of Dobanovići, Popovići and Perovići in Seoca in Crmnica hail from Kelmend.[43] Other families hailing from Kelmend include the Mujzići in Ćirjan, Džaferovići in Besa, and the Velovići, Odžići and Selmanovići in Donji Murići.[44] The Mari and Gorvoki families, constituting the main element of the Koći brotherhood of Kuči, hail from Vukël.[45]

In Rugova, Kosovo, the majority of the modern Albanian population descends from the Kelmendi. The Kelmendi fis in Rugova also include immigrant Shkreli, Kastrati and Shala families. The oldest Kelmendi families in Rugova, the Ljaići, claim descent from a Nika who settled there.[46]

Notable people

- By birth

- Prek Cali (1872–1945), Kelmendi chieftain, rebel leader, World War II guerrilla. Born in Vermosh.

- Nora of Kelmendi (17th century), legendary woman warrior.

- Adrian Aliaj, Albanian footballer. Born in Shkodër.

- By ancestry

- Ali Kelmendi (1900–1939), Albanian communist. Born in Peć.

- Ibrahim Rugova, former President of Kosovo.[47] Born in Istok.

- Majlinda Kelmendi, Kosovan judoka. Born in Peć.

- Jeton Kelmendi, Kosovan writer. Born in Peć.

- Sadri Gjonbalaj, Montenegrin-born American footballer. Born in Vusanje.

- Bajram Kelmendi (1937–1999), Kosovan lawyer and human rights activist. Born in Peć.

- Aziz Kelmendi, Yugoslav soldier and mass murderer. Born in Lipljan.

Annotations

- ^ Kosovo is the subject of a territorial dispute between the Republic of Kosovo and the Republic of Serbia. The Republic of Kosovo unilaterally declared independence on 17 February 2008, but Serbia continues to claim it as part of its own sovereign territory. The two governments began to normalise relations in 2013, as part of the Brussels Agreement. Kosovo has received formal recognition as an independent state from 113 out of 193 United Nations member states.

- ^ Original popoli quasi tutti latini, e di lingua Albanese e Dalmata, of which "Latins" (latini) translates to Catholics, and "Dalmatian language" (lingua Dalmata) to Serbian (Slavic).[18][48]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Elsie 2015, p. 27.

- ↑ Stanojević & Vasić 1975, p. 97.

- 1 2 3 4 Elsie 2015, p. 28.

- ↑ Vasić, Milan (1991), "Etnički odnosi u jugoslovensko-albanskom graničnom području prema popisnom defteru sandžaka Skadar iz 1582/83. godine", Stanovništvo slovenskog porijekla u Albaniji : zbornik radova sa međunarodnog naučnog skupa održanog u Cetinju 21, 22. i 23. juna 1990 (in Serbo-Croatian), OCLC 29549273

- 1 2 3 Stanojević & Vasić 1975, p. 98.

- ↑ Elsie, Robert (2003). Early Albania: a reader of historical texts, 11th-17th centuries. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 159. ISBN 978-3-447-04783-8. Retrieved 18 November 2011.

- ↑ Bolizza (1614). "Mariano Bolizza, report and description of the sanjak of Shkodra (1614)".

- ↑ Kulišić, Špiro (1980). O etnogenezi Crnogoraca (in Montenegrin). Pobjeda. p. 41. Retrieved 19 November 2011.

- ↑ Lambertz, Maximilian (1959). Wissenschaftliche Tätigkeit in Albanien 1957 und 1958. Südost-Forschungen. S. Hirzel. p. 408. Retrieved 19 November 2011.

- ↑ François Lenormant (1866). Turcs et Monténégrins (in French). Paris. pp. 124–128. Retrieved 2013-11-19.

- ↑ Elsie 2015, p. 32.

- 1 2 Bartl, Peter (2007). Albania sacra: geistliche Visitationsberichte aus Albanien. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 139. ISBN 978-3-447-05506-2. Retrieved 18 November 2011.

- 1 2 Mitološki zbornik. Centar za mitološki studije Srbije. 2004. pp. 24, 41–45.

- ↑ Zbornik za narodni život i običaje južnih slavena. 1930. p. 109.

- 1 2 3 4 Karadžić. 2–4. Štamparija Mate Jovanovnića Beograd. 1900. p. 74.

Дрногорци су пристали уз Турке против Клемената и њихових савезника Врћана20), а седамдесет и две године касније, 1685. год., СулеЈман паша Бушатлија успео је да продре на Цетиње само уз припо- моћ Брђана, који су били у завади с Црногорцима.*7! То исто догодило се 1692. год., кад је Сулејман-пагаа поново изишао на Цетиње, те одатле одагнао Млечиће и умирио Црну Гору, коЈ"а је била пристала под заштиту млетачке републике.*8) 0 вери Бр- ђани су мало водили рачуна, да не нападају на своје саплеме- нике, јер им је плен био главна сврха. Од клементашких пак напада нарочито највише су патили Плаво, Гусиње и православнн живаљ у тим крајевима. Горе сам напоменуо да су се ови спуштали и у пећки крај,и тамо су били толико силни, да су им поједина села и паланке морали плаћати данак.

- ↑ Zapisi. 13. Cetinjsko istorijsko društvo. 1940. p. 15.

Марта мјесеца 1688 напао је Сулејман-паша на Куче

- ↑ Malcolm, Noel (1998). Kosovo: a short history. Macmillan. p. 155. ISBN 978-0-333-66612-8. Retrieved 18 November 2011.

- 1 2 Grothusen 1984, p. 146

- ↑ Robert Elsie. p. 32.

- ↑ Mita Kostić, "Ustanak Srba i Arbanasa u staroj Srbiji protivu Turaka 1737-1739. i seoba u Ugarsku", Glasnik Skopskog naučnog društva 7-8, Skoplje 1929, pp. 225, 230, 234

- ↑ Albanische Geschichte: Stand und Perspektiven der Forschung, p. 239 (in German)

- ↑ Borislav Jankulov (2003). Pregled kolonizacije Vojvodine u XVIII i XIX veku. Novi Sad - Pančevo. p. 61.

- 1 2 Gawrych 2006, pp. 186-187.

- ↑ Pearson 2004, p. 43.

- ↑ Südost Forschungen, Vol 59-60, p. 149, (in German)

- ↑ Ndue Bacaj (Gazeta "Malësia") (March 2001), Prek Cali thërret: Rrnoftë Shqipnia, poshtë komunizmi (in Albanian), Shkoder.net, archived from the original on 2013-12-24, retrieved 2013-12-25

- 1 2 Luigj Martini (2005). Prek Cali, Kelmendi dhe kelmendasit (in Albanian). Camaj-Pipaj. p. 66. ISBN 9789994334070.

- ↑ Santayana, Manuel Pardo de; Pieroni, Andrea; Puri, Rajindra K. (2010-05-01). Ethnobotany in the new Europe: people, health, and wild plant resources. Berghahn Books. p. 21. ISBN 978-1-84545-456-2. Retrieved 18 November 2011.

- ↑ Augustin Theiner (1875). Vetera monumenta Slavorum meridionalium historiam illustrantia maximam partem nondum edita ex tabulariis vaticanis deprompta collecta: A Clemente VII. usque ad Pium VII. (1524-1800) cum addimentia saec. XIII. et XIV. Tomus Secundus. Academia scientiarum et artium slavorum meridionalium. p. 218.

Clemente, primo stipite, fu di padre serviano da Moraccia fiume, che scaturisce da Monte Negro sopra Cattaro, e di madre detta Bubesca, figlia di Vrijabegna da Cucci

- 1 2 Elsie 2015.

- ↑ Hecquard 1859, p. 177.

- 1 2 Hecquard 1859, p. 178.

- ↑ Jovičević 1923, pp. 60–61.

- ↑ Milan Šufflay, Povijest sjev. Arb., Arhiv za arbanašku stranu II, 2, Beograd 1924, p. 197 (in Croatian)

- ↑ Slijepčević, Đoko M. (1983). Srpsko-arbanaški odnosi kroz vekove sa posebnim osvrtom na novije vreme. D. Slijepčević.

- ↑ Velimirović, Miloš (1892). Na Komovima. Bratstvo. 5. Beograd. p. 24.

- ↑ Grigorije Božović (1930). Sa sedla i samara. Štamparija "Jedinstvo". p. 123.

- ↑ Jovan N. Tomić, "O Arnautima u Staroj Srbiji i Sandžaku /About the Albanians in the Old Serbia and Sanjak", Belgrade, Geca Kon. (1913), p. 74 (in Serbian)

- ↑ Brastvo. 16. Društvo sv. Save. 1921. p. 176.

Клименти су били пореклом Срби прво православни ...

- ↑ Elsie 2001, p. 152.

- ↑ Gawrych, George (2006). The Crescent and the Eagle: Ottoman rule, Islam and the Albanians, 1874–1913. London: IB Tauris. p. 31. ISBN 9781845112875.

- ↑ Vojska, Volume 8, Issues 405-414 (in Serbian). Vojnoizdavački i novinski centar. 1999. p. 48.

Џомбољај, Уљај, Ахметај, Вучетај... Али оне су пре десетак и више година има- ли презимена Џомболић, Уље- вић, Ахметовић, Вучетовић

- ↑ Petrović 1941, p. 112.

- ↑ Petrović 1941, pp. 111–112.

- ↑ Erdeljanović, Jovan (1907). Kuči - pleme u Crnoj Gori. p. 148.

- ↑ Mihailo Petrović (1941). Đerdapski ribolovi u prošlosti i u sadašnjosti. 74. Izd. Zadužbine Mikh. R. Radivojeviča. pp. 175–176, 184.

- ↑ "VOAL - Online Zëri i Shqiptarëve - PAIONËT E VARDARIT I GJEJMË KELMENDAS NË LUGINËN E DRINITShtegëtimi i paionëve nga liqeni i Shkodrës në luginën e VardaritNga RAMIZ LUSHAJ". www.voal-online.ch.

- ↑ The South Slav Journal. 5–6. Dositey Obradovich Circle. 1983. p. 10.

here begins Serbia, 'che e mediterranea, e arriva verso Danubio.' From here on, Bizzi says that 'la Lingua Dalmata' is spoken, the Serb language which was familiar to him ... (In questi paesi delta Servia si parla la lingua Dalmata)

Sources

- Hecquard, Hyacinthe (1859). "Tribu des Clementi". Histoire et description de la Haute Albanie ou Ghégarie. Paris. pp. 175–197. (in French)

- Elsie, Robert (2015). The Tribes of Albania: History, Society and Culture. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-1-78453-401-1.

- Elsie, Robert (2003). Early Albania: a reader of historical texts, 11th-17th centuries. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3-447-04783-8. Retrieved 18 November 2011.

- Elsie, Robert (2001). A dictionary of Albanian religion, mythology and folk culture. C. Hurst. ISBN 978-1-85065-570-1. Retrieved 18 November 2011.

- Grothusen, Klaus-Detlev (1984). Jugoslawien: Integrationsprobleme in Geschichte und Gegenwart : Beitr̈age des Südosteuropa-Arbeitskreises der Deutschen Forschungsgemeinschaft zum V. Internationalen Südosteuropa-Kongress der Association internationale d'études du Sud-Est européen, Belgrad, 11.-17. September 1984. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. ISBN 978-3-525-27315-9.

- Jovićević, Andrija (1923). Malesija. Rodoljub.

- Pearson, Owen (2004). Albania in the twentieth century: a history. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84511-013-0.

- Petrović, Mihailo (1941). Đerdapski ribolovi u prošlosti i u sadašnjosti. 23-25. Izd. Zadužbine Mikh. R. Radivojevića.

- Stanojević, Gligor; Vasić, Milan (1975). Istorija Crne Gore (3): od početka XVI do kraja XVIII vijeka. Titograd: Redakcija za istoriju Crne Gore. OCLC 799489791.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kelmend. |