Jean-Michel Basquiat

| Jean-Michel Basquiat | |

|---|---|

Jean-Michel Basquiat, 1986, photo by William Coupon. | |

| Born |

December 22, 1960 Brooklyn, New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Died |

August 12, 1988 (aged 27) Manhattan, New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Style | Graffiti, street art, primitivism |

| Movement | Neo-expressionism |

| Website |

basquiat |

Jean-Michel Basquiat (French: [ʒɑ̃ miʃɛl baskija]; December 22, 1960 – August 12, 1988) was an American artist of Haitian and Puerto Rican descent.[1] Basquiat first achieved fame as part of SAMO, an informal graffiti duo who wrote enigmatic epigrams in the cultural hotbed of the Lower East Side of Manhattan during the late 1970s where the hip hop, punk, and street art cultures had coalesced. By the 1980s, he was exhibiting his neo-expressionist paintings in galleries and museums internationally. The Whitney Museum of American Art held a retrospective of his art in 1992.

Basquiat's art focused on "suggestive dichotomies", such as wealth versus poverty, integration versus segregation, and inner versus outer experience.[2] He appropriated poetry, drawing, and painting, and married text and image, abstraction, figuration, and historical information mixed with contemporary critique.[3]

Basquiat used social commentary in his paintings as a "springboard to deeper truths about the individual",[2] as well as attacks on power structures and systems of racism, while his poetics were acutely political and direct in their criticism of colonialism and support for class struggle.[3] He died of a heroin overdose at his art studio at the age of 27.[4]

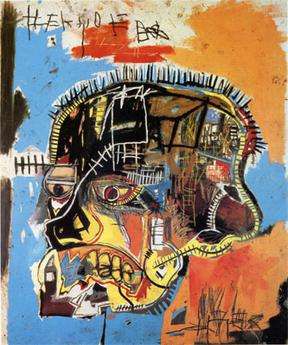

On May 18, 2017, at a Sotheby's auction, a 1982 painting by Basquiat depicting a skull ("Untitled") set a new record high for any American artist at auction, selling for $110.5 million.[5]

Early life

Jean-Michel Basquiat was born in Brooklyn, New York, on December 22, 1960, shortly after the death of his elder brother, Max. He was the second of four children of Matilde Andrades (July 28, 1934 – November 17, 2008)[6] and Gérard Basquiat (1930 – July 7, 2013).[7][8] He had two younger sisters: Lisane, born in 1964, and Jeanine, born in 1967.[6]

His father, Gérard Basquiat, was born in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, and his mother, Matilde Basquiat, who was of Puerto Rican descent, was born in Brooklyn, New York. Matilde instilled a love for art in her young son by taking him to art museums in Manhattan and enrolling him as a junior member of the Brooklyn Museum of Art.[8][9] Basquiat was a precocious child who learned how to read and write by the age of four and was a gifted artist. His teachers, such as artist Jose Machado, noticed his artistic abilities, and his mother encouraged her son's artistic talent. By the age of 11, Basquiat was fully fluent in French, Spanish and English. In 1967, Basquiat started attending Saint Ann's, an arts-oriented exclusive private school.[10][11][12] He drew with Marc Prozzo, a friend from St. Ann's; they together created a children's book, written by Basquiat and illustrated by Prozzo. Basquiat became an avid reader of Spanish, French, and English texts and a more than competent athlete, competing in track events.

In September 1968, at the age of seven, Basquiat was hit by a car while playing in the street. His arm was broken and he suffered several internal injuries, and he eventually underwent a splenectomy.[13] While he was recuperating from his injuries, his mother brought him the Gray's Anatomy book to keep him occupied. This book would prove to be influential in his future artistic outlook. His parents separated that year and he and his sisters were raised by their father.[8][14] The family resided in Boerum Hill, Brooklyn, for five years, then moved to San Juan, Puerto Rico in 1974, where Basquiat studied at Saint John's School in Condado. After two years, they returned to New York City.[15]:39

When he was 13, his mother was committed to a mental institution and thereafter spent time in and out of institutions.[16] At 15, Basquiat ran away from home.[8][15]:37 He slept on park benches in Tompkins Square Park, and was arrested and returned to the care of his father within a week.[8][15]:39

Basquiat dropped out of Edward R. Murrow High School in the tenth grade at the age of 17 and then attended City-As-School, an alternative high school in Manhattan home to many artistic students who failed at conventional schooling. His father banished him from the household for dropping out of high school and Basquiat stayed with friends in Brooklyn. He supported himself by selling T-shirts and homemade post cards.

Career

— Franklin Sirmans, In the Cipher: Basquiat and Hip Hop Culture[3]

Basquiat went from being homeless and unemployed to selling a single painting for up to $25,000 in a matter of several years.[17]

In 1976, Basquiat and friend Al Diaz began spray painting graffiti on buildings in Lower Manhattan, working under the pseudonym SAMO. The designs featured inscribed messages such as "Plush safe he think.. SAMO" and "SAMO as an escape clause". In 1978, Basquiat worked for the Unique Clothing Warehouse in their art department at 718 Broadway in NoHo and at night he began "SAMO" painting his original graffiti[18] art on neighborhood buildings. Unique's founder Harvey Russack discovered Basquiat painting a building one night, they became friends, and he offered him a day job. On December 11, 1978, The Village Voice published an article about the graffiti.[19] When Basquiat and Diaz ended their friendship, The SAMO project ended with the epitaph "SAMO IS DEAD", inscribed on the walls of SoHo buildings in 1979.[4]

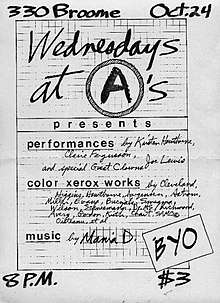

In 1979, Basquiat appeared on the live public-access television show TV Party hosted by Glenn O'Brien, and the two started a friendship. Basquiat made regular appearances on the show over the next few years. That same year, Basquiat formed the noise rock band Test Pattern – which was later renamed Gray – which played at Arleen Schloss's open space, "Wednesdays at A's",[20] where in October 1979 Basquiat showed, among others, his SAMO color Xerox work.

Gray also consisted of Shannon Dawson, Michael Holman, Nick Taylor, Wayne Clifford and Vincent Gallo, and the band performed at nightclubs such as Max's Kansas City, CBGB, Hurrah and the Mudd Club. In 1980, Basquiat starred in O'Brien's independent film Downtown 81, originally titled New York Beat. That same year, Basquiat met Andy Warhol at a restaurant. Basquiat presented to Warhol samples of his work, and Warhol was stunned by Basquiat's genius and allure. The two artists later collaborated. Downtown 81 featured some of Gray's recordings on its soundtrack.[21] Basquiat also appeared in the 1981 Blondie music video "Rapture," in a role originally intended for Grandmaster Flash,[22][23] as a nightclub disc jockey.[24]

The early 1980s were Basquiat's breakthrough as a solo artist. In June 1980, Basquiat participated in The Times Square Show, a multi-artist exhibition sponsored by Collaborative Projects Incorporated (Colab) and Fashion Moda where he was noticed by various critics and curators. In particular Emilio Mazzoli, an Italian gallerist saw the exhibition and invited Basquiat to Modena (Italy) to have his world first solo show, that opened on May 23, 1981. In December 1981, René Ricard published "The Radiant Child" in Artforum magazine.[25] In September 1982, Basquiat joined the Annina Nosei gallery and worked in a basement below the gallery toward his first American one-man show, which took place from March 6 to April 1, 1982.

In March 1982 he worked in Modena, Italy, again to work on his second Italian exhibition and from November, Basquiat worked from the ground-floor display and studio space Larry Gagosian had built below his Venice, California, home and commenced a series of paintings for a 1983 show, his second at Gagosian Gallery, then in West Hollywood.[26] He brought along his girlfriend, then-unknown aspiring singer Madonna.[27] Gagosian recalls, "Everything was going along fine. Jean-Michel was making paintings, I was selling them, and we were having a lot of fun. But then one day Jean-Michel said, 'My girlfriend is coming to stay with me.' I was a little concerned -- one too many eggs can spoil an omelet, you know? So I said, 'Well, what's she like?' And he said, He said, 'Her name is Madonna and she's going to be huge.' I'll never forget that he said that. So Madonna came out and stayed for a few months and we all got along like one big, happy family."[28] During this time he took considerable interest in the work that Robert Rauschenberg was producing at Gemini G.E.L. in West Hollywood, visiting him on several occasions and finding inspiration in the accomplishments of the painter.[26] In 1982, Basquiat worked briefly with musician and artist David Bowie.

In 1983, Basquiat produced a 12-inch rap single featuring hip-hop artists Rammellzee and K-Rob. Billed as Rammellzee vs. K-Rob, the single contained two versions of the same track: "Beat Bop" on side one with vocals and "Beat Bop" on side two as an instrumental.[29] The single was pressed in limited quantities on the one-off Tartown Record Company label. The single's cover featured Basquiat's artwork, making the pressing highly desirable among both record and art collectors.

At the suggestion of Swiss dealer Bruno Bischofberger, Warhol and Basquiat worked on a series of collaborative paintings between 1983 and 1985. In the case of Olympic Rings (1985), Warhol made several variations of the Olympic five-ring symbol, rendered in the original primary colors. Basquiat responded to the abstract, stylized logos with his oppositional graffiti style.[30]

Basquiat often painted in expensive Armani suits and would even appear in public in the same paint-splattered clothes.[31][32]

Drawings

_1982.jpeg)

In his short life, Basquiat produced around 1500 drawings, as well as around 600 paintings and many other sculpture and mixed media works. Basquiat drew constantly, and often used objects around him as surfaces when paper wasn't immediately to hand.[33][34]

From a very young age Basquiat would produce cartoon-inspired drawings alongside his mother, who had an interest in fashion design and sketching. Drawings became central to his work as he developed as an artist.[35] Basquiat's drawings were produced in many different mediums, most commonly ink, pencil, felt-tip or marker, and oil-stick.[36]

Basquiat sometimes used Xerox copies of fragments of his drawings to paste on to the canvas of larger paintings.[37]

The first public showing of Basquiat's paintings and drawings was in 1981: New York/New Wave, at PS1 in Long Island City, brought together by Mudd Club co-founder and curator Diego Cortez. It was a group show that included pieces by William Burroughs, David Byrne, Keith Haring, Nan Goldin and Robert Mapplethorpe.[38][39]

The article in Artforum magazine entitled Radiant Child written by Rene Ricard after seeing the show at PS1, brought Basquiat to the attention of the art world.[40] In 1984 Basquiat immortalised Ricard in two drawings, Untitled (Axe/Rene) and René Ricard,[41][42] representing the tension that existed between them.

A poet as well as an artist, words featured heavily in his drawings and paintings, with direct references to racism, slavery, the people and street scene of 1980s New York including other artists, and black historical figures, musicians and sports stars, as his notebooks and many important drawings demonstrate.[43][44]

Very often Basquiat's drawings were untitled, and as such to differentiate works a word written within the drawing is commonly in parentheses after Untitled, such as with Untitled (Axe/Rene).

After Basquiat died of an overdose at the age of 27, his estate was controlled by his father Gérard Basquiat, who also oversaw the committee which authenticated artworks, and operated from 1993 to 2012 to review over 1000 works, the majority of which were drawings.[45]

Artistic styles

Kellie Jones, Lost in Translation: Jean-Michel in the (Re)Mix[46]

Fred Hoffman hypothesizes that underlying Basquiat's sense of himself as an artist was his "innate capacity to function as something like an oracle, distilling his perceptions of the outside world down to their essence and, in turn, projecting them outward through his creative acts."[2] Additionally, continuing his activities as a graffiti artist, Basquiat often incorporated words into his paintings. Before his career as a painter began, he produced punk-inspired postcards for sale on the street, and became known for the political–poetical graffiti under the name of SAMO. On one occasion Basquiat painted his girlfriend's dress with the words "Little Shit Brown". He would often draw on random objects and surfaces, including other people's property. The conjunction of various media is an integral element of Basquiat's art. His paintings are typically covered with text and codes of all kinds: words, letters, numerals, pictograms, logos, map symbols, diagrams and more.[47]

A middle period from late 1982 to 1985 featured multi-panel paintings and individual canvases with exposed stretcher bars, the surface dense with writing, collage and imagery. The years 1984–85 were also the main period of the Basquiat–Warhol collaborations, even if, in general, they were not very well received by the critics.

A major reference source used by Basquiat throughout his career was the book Gray's Anatomy, which his mother had given him while he was in the hospital aged seven. It remained influential in his depictions of internal human anatomy, and in its mixture of image and text. Other major sources were Henry Dreyfuss' Symbol Sourcebook, Leonardo da Vinci's notebooks, and Brentjes' African Rock Art.

Heads

Heads are seen as a major focal point of some of Basquiat's most seminal works. Two pieces, "Untitled (Scull/Skull)"[48] 1981 and "Untitled (Head)" 1982, held by the Broad Foundation and Maezawa Foundation, respectively, can be seen as primary examples. In reference to the potent image depicted in both pieces, Fred Hoffman writes that Basquiat was likely, "caught off guard, possibly even frightened, by the power and energy emanating from this unexpected image." [49] Further investigation by Fred Hoffman of pieces like "Masonic Lodge" 1983 and Untitled (1983) in his book "The Art of Jean-Michel Basquiat" reveals a deeper interest in the artist's fascination with heads that proves an evolution in the artist's oeuvre from one of raw power to one of more refined cognizance.[50]

Heritage

— Lydia Lee[3]

According to Andrea Frohne, Basquiat's 1983 painting Untitled (History of the Black People) "reclaims Egyptians as African and subverts the concept of ancient Egypt as the cradle of Western Civilization".[51]:439–449 At the center of the painting, Basquiat depicts an Egyptian boat being guided down the Nile River by Osiris, the Egyptian god of the earth and vegetation.[51]:448

On the right panel of the painting appear the words "Esclave, Slave, Esclave". Two letters of the word "Nile" are crossed out and Frohne suggests that, "The letters that are wiped out and scribbled over perhaps reflect the acts of historians who have conveniently forgotten that Egyptians were black and blacks were enslaved."[51]:448 On the left panel of the painting Basquiat has illustrated two Nubian-style masks. The Nubians historically were darker in skin color, and were considered to be slaves by the Egyptian people.[51]:439–449

Throughout the rest of the painting, images of the Atlantic slave trade are juxtaposed with images of the Egyptian slave trade centuries before.[51]:439–449 The sickle in the center panel is a direct reference to the slave trade in the United States, and slave labor under the plantation system. The word "salt" that appears on the right panel of the work refers to the Atlantic slave trade, as salt was another important commodity traded at that time.[51]:439–449

Another of Basquiat's pieces, Irony of Negro Policeman (1981), is intended to illustrate how he believes African-Americans have been controlled by a predominantly Caucasian society. Basquiat sought to portray that African-Americans have become complicit with the "institutionalized forms of whiteness and corrupt white regimes of power" years after the Jim Crow era had ended.[51]:439–449 Basquiat found the concept of a "Negro policeman" utterly ironic. According to him the policeman should sympathize with his black friends, family, and ancestors, yet instead he was there to enforce the rules designed by "white society." The Negro policeman had "black skin but wore a white mask". In the painting, Basquiat depicted the policeman as large in order to suggest an "excessive and totalizing power", but made the policeman's body fragmented and broken.[52]

The hat that frames the head of the Negro policeman resembles a cage, and represents what Basquiat believes are the constrained independent perceptions of African Americans at the time, and how constrained the policeman's own perceptions were within white society. Basquiat drew upon his Haitian heritage by painting a hat that resembles the top hat associated with the gede family of loa, who embody the powers of death in Vodou.[52]:183

However, Kellie Jones, in her essay Lost in Translation: Jean-Michel in the (Re)Mix, posits that Basquiat's "mischievous, complex, and neologistic side, with regard to the fashioning of modernity and the influence and effluence of black culture" are often elided by critics and viewers, and thus "lost in translation."[46]

The art historian Olivier Berggruen situates in Basquiat's anatomical screen prints, titled Anatomy, an assertion of vulnerability, one which "creates an aesthetic of the body as damaged, scarred, fragmented, incomplete, or torn apart, once the organic whole has disappeared. Paradoxically, it is the very act of creating these representations that conjures a positive corporeal valence between the artist and his sense of self or identity."[53]

Exhibitions

Basquiat's first public exhibition was in the group effort The Times Square Show (with David Hammons, Jenny Holzer, Lee Quiñones, Kenny Scharf and Kiki Smith among others), held in a vacant building at 41st Street and Seventh Avenue, New York. In late 1981, Basquiat joined the Annina Nosei gallery in SoHo; his first one-person exhibition was in 1982 at that gallery.[54] By then, he was showing regularly alongside other Neo-expressionist artists including Julian Schnabel, David Salle, Francesco Clemente and Enzo Cucchi. He was represented in Los Angeles by the Gagosian gallery and throughout Europe by Bruno Bischofberger.

Major exhibitions of Basquiat's work have included Jean-Michel Basquiat: Paintings 1981–1984 at the Fruitmarket Gallery, Edinburgh (1984), which traveled to the Institute of Contemporary Arts, London, and Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam, in 1985); the Kestnergesellschaft, Hannover (1987, 1989). The first retrospective to be held of his work was the Jean-Michel Basquiat exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art from October 1992 to February 1993. It subsequently traveled to the Menil Collection, Houston; the Des Moines Art Center, Iowa; and the Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts, Alabama, from 1993 to 1994. The catalog for this exhibition,[55] edited by Richard Marshall and including several essays of differing styles, was a groundbreaking piece of scholarship into Basquiat's work and still is a major source. Another exhibition, Basquiat, was mounted by the Brooklyn Museum, New York, in 2005, and traveled to the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.[30][56] From October 2006 to January 2007, the first Basquiat exhibition in Puerto Rico took place at the Museo de Arte de Puerto Rico (MAPR), produced by ArtPremium, Corinne Timsit and Eric Bonici. Brooklyn Museum exhibited Basquiat: The Unknown Notebooks in April–August 2015.[57] In 2017, the Barbican Centre in London exhibited Basquiat: Boom for Real. Basquiat remains an important source of inspiration for a younger generation of contemporary artists all over the world such as Rita Ackermann and Kader Attia, as showed for example the exhibition Street and Studio: From Basquiat to Séripop co-curated by Cathérine Hug and Thomas Mießgang at Kunsthalle Wien (Austria) in 2010.[58] “Basquait and the Bayou,” a 2014 show presented by the Ogden Museum of Southern Art in New Orleans, focused on the artist’s works with themes of the American South.[59]

Reviews

In a review for The Telegraph, critic Hilton Kramer starts his first paragraph by stating that Basquiat had no idea what the word "quality" meant. The praises to follow are in the lines of "talentless hustler" and "street-smart but otherwise invincibly ignorant" arguing that art dealers of the time were "as ignorant about art as Basquiat himself." In saying that Jean-Michel's work never rose above "that lowly artistic station" of graffiti "even when his paintings were fetching enormous prices," Kramer argued that graffiti art "acquired a cult status in certain New York art circles." Kramer further opined that "As a result of the campaign waged by these art-world entrepreneurs on Basquiat's behalf—and their own, of course—there was never any doubt that the museums, the collectors and the media would fall into line" when talking about the marketization of Basquiat's name.[60]

Art critic Bonnie Rosenberg compares Basquiat's work to the emergence of American Hip Hop during the same era. She also mentions how Basquiat experienced a good taste of fame in his last years when he was a "critically embraced and popularly celebrated artistic phenomenon." Rosenberg remarked that some people focused on the "superficial exoticism of his work" missing the fact that it "held important connections to expressive precursors."[61]

Shortly after his death, The New York Times indicated that Basquiat was "the most famous of only a small number of young black artists who have achieved national recognition."[62]

Final years and death

_home_on_57_Great_Jones_Street.jpg)

By 1986, Basquiat had left the Annina Nosei gallery and was showing at the Mary Boone gallery in SoHo. On February 10, 1985, he appeared on the cover of The New York Times Magazine in a feature titled "New Art, New Money: The Marketing of an American Artist".[63] He was a successful artist in this period, but his growing heroin addiction began to interfere with his personal relationships.

Despite an attempt at sobriety, he died on August 12, 1988, of a heroin overdose at his art studio on Great Jones Street in Manhattan's NoHo neighborhood.[64][65][66] He was 27 years old.[4][67]

Basquiat was interred in Brooklyn's Green-Wood Cemetery, where Jeffrey Deitch made a speech at the graveside. Among those speaking at Basquiat's memorial held at Saint Peter's Church on November 3, 1988, were Ingrid Sischy who, as the editor of Artforum in the 1980s, got to know the artist well and commissioned a number of articles that introduced his work to the wider world.[68] Suzanne Mallouk recited sections of A. R. Penck's "Poem for Basquiat" and Fab 5 Freddy read a poem by Langston Hughes.[69] The 300 guests included musicians John Lurie and Arto Lindsay; artist Keith Haring; poet David Shapiro; Glenn O'Brien, a writer; Fab 5 Freddy; and members of the band Gray, which Basquiat led in the late 1970s.[70] In memory of the late artist, Keith Haring created Pile of Crowns for Jean-Michel Basquiat (1988).[71]

Legacy

| “ | Basquiat speaks articulately while dodging the full impact of clarity like a matador. We can read his pictures without strenuous effort—the words, the images, the colors and the construction—but we cannot quite fathom the point they belabor. Keeping us in this state of half-knowing, of mystery-within-familiarity, had been the core technique of his brand of communication since his adolescent days as the graffiti poet SAMO. To enjoy them, we are not meant to analyze the pictures too carefully. Quantifying the encyclopedic breadth of his research certainly results in an interesting inventory, but the sum cannot adequately explain his pictures, which requires an effort outside the purview of iconography ... he painted a calculated incoherence, calibrating the mystery of what such apparently meaning-laden pictures might ultimately mean. —Marc Mayer Basquiat in History[72] |

” |

Literature

In 1991, poet Kevin Young produced a book, To Repel Ghosts, a compendium of 117 poems relating to Basquiat's life, individual paintings, and social themes found in the artist's work. He published a "remix" of the book in 2005.[73]

In 1995, writer, Jennifer Clement, wrote the book Widow Basquiat, based on the stories told to her by Suzanne Mallouk.

In 2005, poet M. K. Asante published the poem "SAMO", dedicated to Basquiat, in his book Beautiful. And Ugly Too.

Film

Basquiat starred in Downtown 81, a vérité movie written by Glenn O'Brien and shot by Edo Bertoglio in 1981, but not released until 1998.[74] In 1996, eight years after the artist's death, a biographical film titled Basquiat was released, directed by Julian Schnabel, with actor Jeffrey Wright playing Basquiat. David Bowie played the part of Andy Warhol. Schnabel was interviewed during the film's script development as a personal acquaintance of Basquiat. Schnabel then purchased the rights to the project, believing that he could make a better film.[75]

In 2006 the Equality Forum featured Jean-Michel Basquiat during LGBT history month.[76]

A 2009 documentary film, Jean-Michel Basquiat: The Radiant Child, directed by Tamra Davis, was first screened as part of the 2010 Sundance Film Festival and was shown on the PBS series Independent Lens in 2011.[36] Tamra Davis discussed her friendship with Basquiat in a Sotheby's video, "Basquiat: Through the Eyes of a Friend".

The American Public Broadcast Service broadcast a 90-minute documentary about Basquiat in the American Masters series, entitled Basquiat:Rage to Riches, on 14 September 2018.[23]

Music

Shortly after Basquiat's death, Vernon Reid of New York City rock band Living Colour wrote a song called "Desperate People", released on their album Vivid. The song primarily addresses the drug scene of New York at that time. Vernon states that Basquiat's death inspired him to write the song after receiving a phone call from Greg Tate informing Vernon of Basquiat's death.[77]

Basquiat is referenced in Jay-Z and Frank Ocean's song "Oceans": "I hope my black skin don't dirt this white tuxedo before the Basquiat show" in the 2013 album Magna Carta Holy Grail. Both Jay-Z and Kanye West made reference to Basquiat on their 2011 collaborative album Watch the Throne. In "Illest Motherfucker Alive", Jay-Z raps "Basquiats, Warhols serving as my muses" and in "That's My Bitch", West Raps "Basquiat she learning a new word, its yacht". Jay-Z also mentions him on his 2013 album Magna Carta Holy Grail when he says "Yellow Basquiat in my kitchen corner go 'head, lean on that shit Blue, you own it". In his verse on Lil Wayne's song "John", Rick Ross raps "Red on the wall, Basquiat when I paint".

In the song "Ten Thousand Hours", Macklemore raps: "I observed Escher, I love Basquiat", and on his song "Victory Lap" raps: "unorthodox, like Basquiat with a pencil". In his song "Die Like a Rockstar", about overdosing, Danny Brown raps "Basquiat freestyle" to hype himself up. Canadian artist The Weeknd has stated in interviews that his trademark haircut was inspired by Basquiat. ASAP Rocky mentions Basquiat in his song "Phoenix", rapping "Painting vivid pictures/call me Basquiat, Picasso". Rapper Robb Bank$ has a song titled "Look Like Basquiat". Korean rapper Jazzy Ivy released the single/album "Jean & Andy" inspired by Jean-Michel Basquiat and Andy Warhol. "Rich Niggaz" on J. Cole's second album Born Sinner he raps: "It's like Sony signed Basquiat". Referencing his parent label, Sony, he compares Basquiat to himself in the change in their works after signing to a major label. On his song "Untitled", Killer Mike compares himself to Basquiat and 2Pac, saying "This is Basquiat with a passion like Pac". On the track Moments by Kidz in the Hall from their Semester Abroad mixtape Naledge says "look inside myself I think I see a masterpiece, a little Basquiat mix a little Master P".

Korean rapper T.O.P references Basquiat in his 2013 single "DOOM DADA", when he says "MIC-reul jwin shindeullin, rap Basquiat", which translates as: "A god-given rap Basquiat with a mic." On his mixtape Black Hystori Project, Cyhi the Prynce features a song called "Basquiat". Nicki Minaj mentioned Basquiat on her single "Lookin Ass", featured on the Young Money collaborative album Rise Of An Empire. In Riff Raff's "Gucci Jacuzzi", Lil' Flip says "You know I'm makin' guap, and my painting in my kitchen was made by Basquiat". Madonna references Basquiat in the song "Graffiti Heart" from the super deluxe edition of her album Rebel Heart. The band Fall Out Boy used the Basquiat crown as a part of their logo in 2013. It is still being used. Robb Bank$ compares himself thoroughly to Basquiat in his song "Look like Basquiat". Basquiat was referenced in the Gym Class Heroes' song, "To Bob Ross with Love". Hip-hop artist Yasiin Bey released a song dedicated to Basquiat, titled "Basquiat Ghostwriter". Bey says he was inspired by the paintings and writings of the artist.

In the world of jazz, clarinetist Don Byron composed and performed the tune "Basquiat" on his 2000 album A Fine Line: Arias and Lieder. In 2018, Jon Batiste released an album named after Basquiat's painting, "Hollywood Africans".[78]

Basquiat's work has been used by clothing companies such as SPRZ NY of Uniqlo,[79] Urban Outfitters, and Redbubble.

Sexuality

Jennifer Clement (a friend of his long-term girlfriend Suzanne Mallouk) specifically described his sexuality as:

| “ | ...not monochromatic. It did not rely on visual stimulation, such as a pretty girl. It was a very rich multichromatic sexuality. He was attracted to people for all different reasons... It was, I think, driven by intelligence. He was attracted to intelligence more than anything and to pain.[80] | ” |

Collections

Notable private collectors of Basquiat's work include David Bowie, Mera and Donald Rubell,[81] Lars Ulrich,[82] Steven A. Cohen,[81] Laurence Graff,[81] John McEnroe,[81] Madonna,[81] Debbie Harry, Leonardo DiCaprio,[83] Swizz Beatz,[84] Jay-Z[85] and Johnny Depp.[86]

Art market

Basquiat sold his first painting in 1981, and by 1982, spurred by the Neo-Expressionist art boom, his work was in great demand. In 1985, he was featured on the cover of The New York Times Magazine in connection with an article on the newly exuberant international art market; this was unprecedented for an African-American artist, and for an artist so young.[74] Since Basquiat's death in 1988, his market has developed steadily—in line with overall art market trends—with a dramatic peak in 2007 when, at the height of the art market boom, the global auction volume for his work was over $115 million. Brett Gorvy, deputy chairman of Christie's, is quoted describing Basquiat's market as "two-tiered. [...] The most coveted material is rare, generally dating from the best period, 1981–83."[87]

In 2001 New York artist and con-artist Alfredo Martinez was charged by the Federal Bureau of Investigation with attempting to deceive two art dealers by selling them $185,000 worth of fake drawings put forth as being the work of Basquiat.[88] The charges against Martinez, which landed him in Manhattan's Metropolitan Correction Center on June 19, 2002, involved an alleged scheme to sell fake Basquiat drawings, accompanied by forged certificates of authenticity.[89]

Until 2002, the highest amount paid for an original work of Basquiat's was US$3,302,500, set on November 12, 1998, at Christie's. In 2002, Basquiat's Profit I (1982), a large piece measuring 86.5 by 157.5 inches (220 by 400 cm), was set for auction again at Christie's by drummer Lars Ulrich of the heavy metal band Metallica. It sold for US$5,509,500.[90] The proceedings of the auction are documented in the film Some Kind of Monster.

In 2008, at another auction at Christie's, Ulrich sold a 1982 Basquiat piece, Untitled (Boxer), for US $13,522,500 to an anonymous telephone bidder. Another record price for a Basquiat painting was made in 2007, when an untitled Basquiat work from 1981 sold at Sotheby's in New York for US$14.6 million.[91] In 2012, for the second year running, Basquiat was the most coveted contemporary (i.e. born after 1945) artist at auction, with €80 million in overall sales.[92] That year, his Untitled (1981), a painting of a haloed, black-headed man with a bright red skeletal body, depicted amid the artist's signature scrawls, was sold by Robert Lehrman for $16.3 million, well above its $12 million high estimate.[93] A similar untitled piece, also undertaken in 1981 and formerly owned by the Israel Museum, sold for £12.92 million at Christie's London, setting a world auction record for Basquiat's work.[94] In 2013, Basquiat's piece Dustheads sold for $48.8 million at Christie's. In 2016 an untitled piece sold at Christie's for $57.3 million to a Japanese businessman and collector, Yusaku Maezawa.[95][96]

In 2017, Yusaku purchased Basquiat's Untitled (1982), a powerful depiction of a skull, at auction for a record-setting US$110,487,500—the most ever paid for an American artwork[5][97][98][99] and the sixth most expensive artwork sold at an auction,[99] surpassing Andy Warhol's Silver Car Crash (Double Disaster) which sold in 2013 for $105 million.[100]

Authentication Committee

The Authentication Committee of the Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat was formed by the gallery that was assigned to handle the artist's estate.[101] Between 1994 and 2012, it reviewed over 2,000 works of art; the cost of the committee's opinion was $100.[101] The committee was headed by Gérard Basquiat. Members and advisers varied depending on who was available when a piece was being authenticated, but they have included the curators and gallerists Diego Cortez, Jeffrey Deitch, John Cheim, Richard Marshall, Fred Hoffman and Annina Nosei (the artist's first art dealer).[102]

In 2008 the authentication committee was sued by collector Gerard De Geer, who claimed the committee breached its contract by refusing to offer an opinion on the authenticity of the painting Fuego Flores (1983);[103] after the lawsuit was dismissed, the committee ruled the work genuine.[104] In early 2012, the committee announced that it would dissolve in September of that year and no longer consider applications.

References

- ↑ Braziel, Jana Evans (2008). Artists, Performers, and Black Masculinity in the Haitian Diaspora. Indiana University Press. p. 174. ISBN 978-0-253-35139-5.

- 1 2 3 Hoffman, Fred. (2005) The Defining Years: Notes on Five Key Works from the book Basquiat. Mayer, Marc (ed.). Merrell Publishers in association with the Brooklyn Museum, ISBN 1-85894-287-X, pp. 129–139.

- 1 2 3 4 Sirmans, Franklin. (2005) In the Cipher: Basquiat and Hip Hop Culture from the book Basquiat. Mayer, Marc (ed.). Merrell Publishers in association with the Brooklyn Museum, ISBN 1-85894-287-X, pp. 91–105.

- 1 2 3 Cf. Fretz, pp. 46–47.

- 1 2 Pogrebin, Robin; Reyburn, Scott, eds. (May 18, 2017). "A Basquiat Sells for 'Mind-Blowing' $110.5 Million at Auction". The New York Times. Retrieved June 13, 2017.

- 1 2 "In Loving Memory: Matilde Basquiat" Archived July 12, 2011, at the Wayback Machine., Lodge Communications 185, Harry S Truman Lodge No.1066, F.&A.M., December 4, 2008. New York, NY. Sad Tidings for Brother John Andrades.

- ↑ "Jean-Michel Basquiat's Dad Leaves Behind Son's Art, and Tax Problem" Archived May 4, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. by James Fanelli, September 5, 2013, 6:27am.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hyped to Death by The New York Times (August 9, 1998).

- ↑ Kwame, Anthony Appiah; Gates, Henry Louis (2005). Africana: Arts and Letters : An A-to-Z Reference of Writers, Musicians, and Artists of the African American Experience. Running Press. p. 69. ISBN 0-7624-2042-1.

- ↑ Phoebe Hoban, "One Artist Imitating Another," The New York Times

- ↑ Arthur C. Danto, "Flyboy in the Buttermilk," "The Nation"

- ↑ Lisa J. Curtis, "Homecoming: Fort Greene's poet-painter Basquiat is fondly remembered," "Brooklyn Paper"

- ↑ Emmerling, Leonard (2003). Jean-Michel Basquiat: 1960–1988. Taschen. p. 11. ISBN 3-822-81637-X.

- ↑ Basquiat's Estate Sells at Sotheby's Archived March 4, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. by Lindsay Pollock (March 31, 2010).

- 1 2 3 Hoban, Phoebe (September 26, 1988). "SAMO Is Dead: The Fall of Jean Michel Basquiat". New York. 21 (38). pp. 36–44. ISSN 0028-7369.

- ↑ Fretz, Eric. Jean-Michel Basquiat: A Biography Archived February 1, 2016, at the Wayback Machine.. Greenwood Press, 2010. ISBN 978-0-313-38056-3. Cf. p. xv

- ↑ "New Art, New Money". www.nytimes.com. Retrieved April 11, 2017.

- ↑ Harvey Russack, founder, owner, and CEO of Unique Clothing Warehouse 1971–1992.

- ↑ Faflick, Philip. "The SAMO Graffiti… Boosh-Wah or CIA?" Village Voice, December 11, 1978: p. 41.

- ↑ "Jean Michel Basquiat Test Pattern". Mutual Art Inc.

- ↑ Andy Kellman. Downtown 81 Original Soundtrack. Retrieved January 16, 2008.

- ↑ "Rock Meets Rap" on Pop-Up Video.

- 1 2 American Masters — Basquiat:Rage to Riches (Season 32, Episode 7). Public Broadcasting Service. Broadcast: 2018-09-14.

- ↑ "Jean-Michel Basquiat: Artist Biography-Early Training". The Art Story Foundation. 2011. Retrieved October 12, 2011.

- ↑ Rene Ricard. "The Radiant Child", Artforum, Volume XX No. 4, December 1981. pp. 35–43 Archived December 28, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 Fred Hoffman (March 13, 2005), Basquiat's L.A. – How an '80s interlude became a catalyst for an artist's evolution Los Angeles Times.

- ↑ Jones, Alice (January 10, 2013). "Larry Gagosian reminisces about the days Madonna was his driver". The Independent. London.

- ↑ "Larry Gagosian – Interview Magazine". Interview Magazine. November 27, 2012. Retrieved November 1, 2017.

- ↑ "Rammellzee vs. K-Rob 12" single produced by Jean-Michel Basquiat". Archived from the original on February 6, 2010. Retrieved January 13, 2012.

- 1 2 Jean-Michel Basquiat and Andy Warhol: Olympic Rings, June 19 – August 11, 2012 Gagosian Gallery, London.

- ↑ Cork, Richard (2003). New Spirit, New Sculpture, New Money: Art in the 1980s. Yale University Press. p. 147. ISBN 0-300-09509-0.

- ↑ Randy P. Conner, David Hatfield Sparks, Queering Creole Spiritual Traditions, Haworth Press, 2004, p. 299. ISBN 1-56023-351-6

- ↑ Cumming, Laura (September 24, 2017). "Basquiat: Boom for Real review – restless energy". the Guardian. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- ↑ "Jean-Michel Basquiat facts, information, pictures | Encyclopedia.com articles about Jean-Michel Basquiat". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- ↑ Steel, Rebecca. "The Art of Jean-Michel Basquiat: Legacy of a Cultural Icon". Culture Trip. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- 1 2 Davis, Tamra. "Jean-Michel Basquiat: The Radiant Child" (One of the "Film Topics" sub-sections on the Independent Lens website and the documentary of the same name they describe). Independent Lens. PBS. Retrieved March 30, 2011.

Tamra Davis explains why she locked her footage of her friend Basquiat in a drawer for two decades, and what it took to be sure a film about him took the full measure of the man.

- ↑ Haden-Guest, Anthony. "Jean-Michel Basquiat". Retrieved April 20, 2018.

- ↑ Sawyer, Miranda (September 3, 2017). "The Jean-Michel Basquiat I knew…". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- ↑ "Debunking Basquiat's Myths: What We Get Wrong About the Misunderstood Artist | artnet News". artnet News. September 18, 2017. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- ↑ Holzwarth, Hans W. (2009). 100 Contemporary Artists A-Z (Taschen's 25th anniversary special ed.). Köln: Taschen. pp. 54–61. ISBN 978-3-8365-1490-3.

- ↑ "Rene Ricard / Axe by Jean-Michel Basquiat". Curiator. Retrieved March 1, 2018.

- ↑ "René Ricard by Jean-MichelBasquiat". www.artnet.com. Retrieved March 1, 2018.

- ↑ "Glenn O'Brien on the notebooks and drawings of Jean-Michel Basquiat". www.artforum.com. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- ↑ Magazine, Wallpaper* (April 7, 2015). "Inner workings: the notebooks of Jean-Michel Basquiat are unveiled at the Brooklyn Museum". Wallpaper*. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- ↑ "Jean-Michel Basquiat's Dad Leaves Behind Son's Art, and Tax Problem". DNAinfo New York. Archived from the original on April 20, 2018. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- 1 2 Lost in Translation: Jean-Michel in the (Re)Mix, by Kellie Jones, from the book Basquiat, edited by Marc Mayer, 2005, Merrell Publishers in association with the Brooklyn Museum, ISBN 978-1-85894-287-2, pp. 163–179.

- ↑ Berger, John (2011). "Seeing Through Lies: Jean-Michael Basquiat". Harper's. Harper's Foundation. 322 (1, 931): 45–50. Retrieved July 18, 2011.

- ↑ https://www.wikiart.org/en/jean-michel-basquiat/head

- ↑ Hoffman, Fred. "The Defining Years: Notes on Five Key Works," in Ibid., p. 13)

- ↑ Hoffman, Fred. "The Art of Jean-Michel Basquiat", Gallerie Enrico Navarra / 2017

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Frohne, Andrea (1999). "Representing Jean-Michel Basquiat". In Okpewho, Isidore; Davies, Carole Boyce; Mazrui, Ali AlʼAmin. The African Diaspora: African Origins and New World Identities (1st ed.). Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. pp. 439–451. ISBN 978-0-253-33425-1.

- 1 2 Braziel, Jana Evans (2008). "Trans-American Art on the Streets: Jean-Michel Basquiat's Black Canvas Bodies and Urban Vodou-Art in Manhattan". Artists, Performers, and Black Masculinity in the Haitian Diaspora. Blacks in the Diaspora. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. pp. 183–198. ISBN 978-0-253-21978-7. LCCN 2007051595. OCLC 177008074. OL 9357461W.

- ↑ Berggruen, Olivier (2011). "Some Notes on Jean-Michel Basquiat's Silk-Screen Prints". The Writing of Art. Pushkin Press. p. 127. ISBN 978 1 906548 62 9.

- ↑ Jean-Michel Basquiat MoMA Collection, New York.

- ↑ Marshall, Richard. Jean-Michel Basquiat, Abrams / Whitney Museum of American Art, 1992 (out of print).

- ↑ Mayer, Marc, Hoffman Fred, et al. Basquiat, Merrell Publishers / Brooklyn Museum, 2005.

- ↑ "Brooklyn Museum: Exhibitions". BrooklynMuseum.org. Retrieved December 29, 2016.

- ↑ Synopsis of the exhibition concept and list of artists

- ↑ MacCash, Doug (2014-11-11). "'Basquiat and the Bayou,' the No. 1 Prospect.3 art festival stop in New Orleans". NOLA.com. Retrieved 2018-10-09.

- ↑ "He had everything but talent". March 22, 1997. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved December 5, 2017.

- ↑ "Jean-Michel Basquiat Biography, Art, and Analysis of Works". The Art Story. Retrieved December 5, 2017.

- ↑ Wines, Michael (August 27, 1988). "Jean Michel Basquiat: Hazards Of Sudden Success and Fame". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 5, 2017.

- ↑ Cathleen McGuigan, "New Art, New Money", The New York Times Magazine, February 2005.

- ↑ Haden-Guest, Anthony. "Jean-Michel Basquiat". The Hive. Vanity Fair. Retrieved November 16, 2017.

Much has been written about the heroin-linked death of Jean-Michel Basquiat. But one voice was missing—that of the wildly talented, wildly extravagant painter himself. Anthony Haden-Guest interviewed America's foremost black artist in the last stages of his blazing trail, as he careened between art dealers and drug dealers.

- ↑ Matheson, Whitney (August 12, 2013). "Look back: Jean-Michel Basquiat died 25 years ago today". USA Today. Retrieved November 16, 2017.

Twenty-five years ago today, the world lost one of the most significant visual artists of the late 20th century: Jean-Michel Basquiat. ¶ Basquiat, who died of a heroin overdose when he was just 27, achieved such an abrupt rise to fame that, sadly, it wasn't so surprising his life ended tragically.

- ↑ Dowd, Vincent (September 25, 2017). "Jean-Michel Basquiat: The neglected genius". BBC News. Retrieved November 16, 2017.

The painter's death of a heroin overdose came when he was 27—a fact which tended to cement his image as the art world equivalent of a rock star (of the 27 Club). Stein says the comparison is a valid one. 'In many ways he was a rock star. And the more I've looked since at the trajectory of his life, the more I realise that in the 1980s Jean-Michel was not looked after by the people who needed to look after him.'

- ↑ Brothers, Thomas (2001). Artists, Writers, and Musicians: an Encyclopedia of People Who Changed the World. 4. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 16. ISBN 1-57356-154-1.

- ↑ Sischy, Ingrid (May 2014). "For The Love of Basquiat". Vanity Fair. Retrieved December 29, 2016.

- ↑ Phoebe Hoban: Basquiat – A Quick Killing in Art The New York Times Books.

- ↑ "Basquiat Memorial", The New York Times, November 3, 1988

- ↑ Muir, Robin (May 7, 1999). "Keith Haring". The Independent. Retrieved December 29, 2016.

- ↑ Basquiat, edited by Marc Mayer, 2005, Merrell Publishers in association with the Brooklyn Museum, ISBN 978-1-85894-287-2, p. 50.

- ↑ Kevin Young, To Repel Ghosts (1st edition), Zoland Books, 2001.

- 1 2 Jean-Michel Basquiat, February 7 – April 6, 2013 Gagosian Gallery, New York.

- ↑ "Meet the Artist: Julan Schnabel", lecture given at Hirshhorn Museum, Washington, DC, May 13, 2011.

- ↑ "Jean-Michel Basquiat". lgbthistorymonth.com.

- ↑ GuitarManiaEU (March 30, 2013). "Living Colour – Interview with Vernon Reid". Retrieved December 29, 2016 – via YouTube.

- ↑ https://www.billboard.com/articles/columns/pop/8477054/jon-batiste-hollywood-africans-interview-basquiat

- ↑ "Jean-michel basquiat | SPRZ NY". sprzny.uniqlo.com. Retrieved November 29, 2015.

- ↑ Clement, Jennifer (2014). Widow Basquiat: A Love Story. Broadway Books. ISBN 978-0553419917.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Adam, Georgina; Harris, Gareth (June 17, 2010). "Basquiat comes of age". theartnewspaper.com. Archived from the original on September 21, 2013.

- ↑ Eddy, Chuck (2011). Rock and Roll Always Forgets: A Quarter Century of Music Criticism. Duke University Press. p. 105. ISBN 0-822-35010-6.

- ↑ Pasori, Cedar (April 22, 2013). "Leonardo DiCaprio Talks Saving the Environment with Art, Collecting Basquiat, and Being Named After da Vinci". complex.com. Retrieved December 2, 2014.

- ↑ "Jay-Z Cops Basquiat Painting From Swizz Beatz". vibe.com. June 30, 2013. Retrieved December 2, 2014.

- ↑ Sheehy, Kate (November 20, 2013). "Jay Z snaps up $4.5M Basquiat painting". nypost.com. Retrieved December 2, 2014.

- ↑ France, Lisa Respers (June 10, 2016). "Johnny Depp auctioning off multimillion-dollar art collection". CNN.com. Retrieved June 11, 2016.

- ↑ Georgina Adam and Gareth Harris (June 17, 2010), Basquiat comes of age The Art Newspaper. Archived August 22, 2010, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Basquiat Forger Arrested By FBI". ArtDaily. Retrieved February 8, 2014.

- ↑ "'How to Fake a Piece of Art' by Artist Alfredo Martinez". InEnArt. Retrieved November 22, 2013.

- ↑ Horsley, Carter. "Art/Auctions: Post-War & Contemporary Art evening auction, May 14, 2002 at Christie's". Retrieved January 17, 2008.

- ↑ "Huge bids smash modern art record". BBC. May 16, 2007. Retrieved May 16, 2007.

- ↑ Charlotte Burns and Julia Michalska (October 11, 2012), Artprice survey reveals the twin peaks of power, The Art Newspaper.

- ↑ Carol Vogel (May 10, 2012), Basquiat Painting Brings $16.3 Million at Phillips Sale The New York Times.

- ↑ Souren Melikian (June 29, 2012), Wary Buyers Still Pour Money Into Contemporary Art International Herald Tribune.

- ↑ Robin Pogrebin, The New York Times May 15, 2016

- ↑ "Basquiat's Most Expensive Works at Auction". Artnet.com. May 16, 2016. Retrieved December 29, 2016.

- ↑ D'Zurilla, Christie, ed. (May 18, 2017). "Basquiat painting sells for $110.5 million, the most ever paid for an American artwork". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved June 13, 2017.

- ↑ Dwyer, Colin, ed. (May 19, 2017). "At $110.5 Million, Basquiat Painting Becomes Priciest Work Ever Sold By A U.S. Artist". NPR. Retrieved June 13, 2017.

- 1 2 Press, ed. (May 24, 2017). "A Price on Genius". The Index. Retrieved June 13, 2017.

- ↑ Mullen, Jethro, ed. (May 19, 2017). "Basquiat tops Warhol after painting sells for $111 million". CNN Money. Retrieved June 13, 2017.

- 1 2 Daniel Grant (September 29, 1996), The tricky art of authentication Baltimore Sun.

- ↑ Liza Ghorbani (September 18, 2011), The Devil on the Door New York Magazine.

- ↑ Kate Taylor (May 1, 2008), Lawsuits Challenge Basquiat, Boetti Authentication Committees New York Sun.

- ↑ Georgina Adam and Riah Pryor (December 11, 2008), The law vs scholarship The Art Newspaper. Archived May 15, 2013, at the Wayback Machine.

Further reading

- Buchhart, Dieter, Glenn O'Brien, Jean-Louis Prat, Susanne Reichling. Jean-Michel Basquiat, Hatje Cantz, 2010. ISBN 978-3-7757-2593-4

- Buchhart, Dieter, and Eleanor Nairne. Basquiat: Boom for Real. (Catalogue for 2017 Exhibition at the Barbican Centre.) London: Prestel Publishing, 2017. ISBN 9783791356365

- Clement, Jennifer: Widow Basquiat, Broadway Books, 2014. ISBN 978-0553419917

- Deitch J., D. Cortez, and Glen O'Brien. Jean-Michel Basquiat: 1981: the Studio of the Street, Charta, 2007. ISBN 978-88-8158-625-7

- Fretz, Eric. Jean-Michel Basquiat: A Biography. Greenwood, 2010. ISBN 978-0-313-38056-3

- Hoban, Phoebe. Basquiat: A Quick Killing in Art (2nd edn), Penguin Books, 2004.

- Hoffman, Fred. "Jean-Michel Basquiat Drawing: Work from the Schorr Family Collection", Rizzoli/Acquavella Galleries, 2014. ISBN 978-0-8478-4447-0

- Hoffman, Fred. "The Defining Years: Notes on Five Key Works," in Basquiat / Merrell Publishers / Brooklyn Museum, 2005, p. 13)

- Hoffman, Fred. "The Art of Jean-Michel Basquiat", Gallerie Enrico Navarra / 2017 ISBN 978-2911596537

- Marenzi, Luca. Jean-Michel Basquiat. Charta, 1999. ISBN 978-88-8158-239-6

- Marshall, Richard. Jean-Michel Basquiat, Abrams / Whitney Museum of American Art. Hardcover 1992, paperback 1995. (Catalog for 1992 Whitney retrospective, out of print).

- Marshall, Richard. Jean-Michel Basquiat: In World Only. Cheim & Read, 2005. (out of print).

- Mayer, Marc, Fred Hoffman, et al. Basquiat, Merrell Publishers / Brooklyn Museum, 2005.

- Tate, Greg. Flyboy in the Buttermilk. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1992. ISBN 978-0-671-72965-3

External links

| Library resources about Jean-Michel Basquiat |

| By Jean-Michel Basquiat |

|---|

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jean-Michel Basquiat. |

- Official website

- Brooklyn Museum Website of the 2005 Basquiat retrospective exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum.

- Jean-Michel Basquiat at the Fun Gallery, excerpt from "Young Expressionists" (ART/New York #19), video, 1982.

- Jean-Michel Basquiat, BBC World Service documentary on Basquiat