Public art

Public art is art in any media that has been planned and executed with the intention of being staged in the physical public domain, usually outside and accessible to all. Public art is significant within the art world, amongst curators, commissioning bodies and practitioners of public art, to whom it signifies a working practice of site specificity, community involvement and collaboration. Public art may include any art which is exhibited in a public space including publicly accessible buildings, but often it is not that simple. Rather, the relationship between the content and audience, what the art is saying and to whom, is just as important if not more important than its physical location.[1]

Scope

Cher Krause Knight states, "art's publicness rests in the quality and impact of its exchange with audiences ... at its most public, art extends opportunities for community engagement but cannot demand particular conclusion”, it introduces social ideas but leaves room for the public to come to their own conclusions.[1] In recent years, public art has increasingly begun to expand in scope and application — both into other wider and challenging areas of artform, and also across a much broader range of what might be called our 'public realm'. Such cultural interventions have often been realised in response to creatively engaging a community's sense of 'place' or 'well-being' in society.

Monuments, memorials and civic statuary are perhaps the oldest and most obvious form of officially sanctioned public art, although it could be said that architectural sculpture and even architecture itself is more widespread and fulfills the definition of public art. Independent artwork, created and installed without being officially sanctioned is ubiquitous in nearly every city.[2][3] It is also installed in natural settings, and can include works such as sculpture, or may be short-lived, such as a precarious rock balance or an ephemeral instance of colored smoke.[4][5][6] Some has been installed underwater.[7]

Permanent works are sometimes integrated with architecture and landscaping in the creation or renovation of buildings and sites, an especially important example being the programme developed in the new city of Milton Keynes, England. Public art is not confined to physical objects; dance, street theatre and even poetry have proponents that specialize in public art.

Some artists working in this discipline use the freedom afforded by an outdoor site to create very large works that would be unfeasible in a gallery, for instance Richard Long's three-week walk, entitled "The Path is the Place in the Line". In a similar example, sculptor Gar Waterman created a giant arch straddling a city street in New Haven, Connecticut.[8] Amongst the works of the last thirty years that have met greatest critical and popular acclaim are pieces by Christo, Robert Smithson, Dennis Oppenheim, Andy Goldsworthy, James Turrell and Antony Gormley, whose work reacts to or incorporates its environment.

Artists making public art range from the greatest masters such as Michelangelo, Pablo Picasso, and Joan Miró, to those who specialize in public art such as Claes Oldenburg and Pierre Granche, to anonymous artists who make surreptitious interventions.

In Cape Town, South Africa, Africa Centre presents the Infecting the City Public Art Festival. Its curatorial mandate is to create a week-long platform for public art - whether it be visual or performative artworks, or artistic interventions - that shake up the city spaces and allows the city's users to view the cityscapes in new and memorable ways. The Infecting the City Festival believes that public art should be freely accessible to everybody in a public space.[9]

History of public art

In the 1930s, the production of national symbolism implied by 19th century monuments starts being regulated by long-term national programs with propaganda goals (Federal Art Project, United States; Cultural Office, Soviet Union). Programs like President Roosevelt's New Deal facilitated the development of public art during the Great Depression but was wrought with propaganda goals. New Deal art support programs intended to develop national pride in American culture while avoiding addressing the faltering economy that said culture was built upon.[1] Although problematic, New Deal programs such as FAP altered the relationship between the artist and society by making art accessible to all people.[1] The New Deal program Art-in-Architecture (A-i-A) developed percent for art programs, a structure for funding public art still utilized today. This program gave one half of one percent of total construction costs of all government buildings to purchase contemporary American art for that structure.[1] A-i-A helped solidify the principle that public art in the US should be truly owned by the public. They also established the legitimacy of the desire for site-specific public art.[1] While problematic at times, early public art programs set the foundation for current public art development.

This notion of public art radically changes during the 1970s, following up to the civil rights movement’ claims on the public space, the alliance between urban regeneration programs and artistic interventions at the end of the 1960s and the revision of the notion of sculpture.[10] In this context, public art acquires a status which goes beyond mere decoration and visualization of official national histories in public space, therefore gaining autonomy as a form of site construction and intervention in the realm of public interests. Public art became much more about the public.[1] This change of perspective is also present by the reinforcement of urban cultural policies in these same years, for example the New York-based Public Art Fund (1977) and several urban or regional Percent for Art programs in the United States and Europe. Moreover, the re-centring of public art discourse from a national to a local level is consistent with the site-specific turn and the critical positions against institutional exhibition spaces emerging in contemporary art practices since the 1960s. The will to create a deepest and more pertinent connection between the production of the artwork and the site where it is made visible prompts different orientations. In 1969 Wolf Vostells Stationary traffic was made in Cologne.

Land artists choose to situate large-scale, process-oriented interventions in remote landscape situations; the Spoleto Festival (1962) creates an open-air museum of sculptures in the medieval city of Spoleto, and the German city of Münster starts, in 1977, a curated event bringing art in public urban places every 10 years (Skulptur Projekte Münster). In the group show When Attitudes Become Form,[11] the exhibition situation is expanded in the public space by Michael Heizer and Daniel Buren’s interventions; architectural scale emerges in the work of artists such as Donald Judd as well as in Gordon Matta-Clark’s temporary interventions in dismissed urban buildings.

Environmental public art

Between the 1970s and the 1980s, gentrification and ecological issues surface in public art practices both as a commission motive and as a critical focus brought in by artists. The individual, Romantic retreat element implied in the conceptual structure of Land art and its will to reconnect the urban environment with nature, is turned into a political claim in projects such as Wheatfield – A Confrontation (1982), by American artist Agnes Denes, as well as in Joseph Beuys’ 7000 Oaks (1982). Both projects focus on the raise of ecological awareness through a green urban design process, bringing Denes to plant a two-acre field of wheat in downtown Manhattan and Beuys to plant 7000 oaks coupled with basalt blocks in Kassel, Germany in a guerrilla or community garden fashion. In recent years, programs of green urban regeneration aiming at converting abandoned lots into green areas regularly include public art programs. This is the case of High Line Art, 2009, a commission program for the High Line, derived from the conversion of a portion of railroad in New York City; and of Gleisdreieck, 2012, an urban park derived from the partial reconversion of a railway station in Berlin which hosts, since 2012, an open-air contemporary art exhibition.

The 1980s also witness the institutionalisation of sculpture parks as curated programs. While the first public and private open-air sculpture exhibitions and collections dating back to the 1930s[12] aim at creating an appropriate setting for large-scale sculptural forms difficult to show in museum galleries, experiences such as Noguchi’s garden in Queens, New York (1985) state the necessity of a permanent relationship between the artwork and its site.

This line also develops in Donald Judd’s project for the Chinati Foundation (1986) in Texas, advocating for the permanent nature of large-scale installations, which fragility may be destroyed when re-locating the work. The trial instructed by judge Edward D. Re in 1985 to re-locate American artist Richard Serra’s Tilted Arc, a monumental intervention commissioned for Manhattan's Federal Plaza by the “Art-in-Architecture” Program, also contributes to the debate about public art site-specificity. In his line of defence for the trial, Richard Serra claims: “Tilted Arc was commissioned and designed for one particular site: Federal Plaza. It is a site-specific work and as such not to be relocated. To remove the work is to destroy the work”. The trial around Tilted Arc shows the essential role played by site-specificity in public art. Moreover, one of the arguments brought into the trial by judge Edward D. Re is the intolerance of the community of users of the Federal Plaza towards Serra’s intervention and the support of the art community, represented by art critic Douglas Crimp’s testimony. In both cases, the audience positions itself as a major factor of the artistic intervention in public space. Within this context, the definition of public art comes to include artistic projects focusing on public issues (democracy, citizenship, integration); participative artistic actions involving the community; artistic projects commissioned and/or funded by a public body, within the Percent for Art schemes, or by a community.

New genre public art in the 1990s: anti-monuments and memorial practices

In the 1990s, the clear differentiation of these new practices from previous forms of artistic presence in the public space calls for alternative definitions, some of them more specific (contextual art, relational art, participatory art, dialogic art, community-based art, activist art), other more comprehensive, such as “new genre public art”.

In this way, public art functions as a social intervention. Artists became fully engaged in civic activism by the 1970s and many adopted a pluralist approach to public art.[1] This approach eventually developed into the “new genre public art”, which is defined by Suzanne Lacy as “socially engaged, interactive art for diverse audiences with connections to identity politics and social activism”.[1] Rather than metaphorically discussing social issues, as did previous public art, practitioners of the “new genre” wanted to explicitly empower marginalized groups, all while maintaining aesthetic appeal.[1] Curator Mary Jane Jacob of "Sculpture Chicago” developed a show, ‘’Culture in Action’’, in summer 1993 that followed principles of new genre public art. The show intended to investigate social systems though audience participatory art, engaging especially with audiences that typically did not participate in traditional art museums.[1] While controversial, Culture in Action introduced new models for community participation and interventionist public art that reaching beyond the “new genre”.

Earlier groups also used public art as an avenue for social intervention. In the 1960s and 70s, the artist collective Situationist International created work that “challenged the assumptions of everyday life and its institutions” through physical intervention.[1] Another artists collective interested in social intervention, Guerrilla Girls, started in the 1980s and persists today. Their public art exposes latent sexism and works to deconstruct male power structures in the art world. Currently, they also address racism in the art world, homelessness, AIDS, and rape culture, all socio-cultural issues the greater world experiences.[1]

02_(cropped).jpg)

In artist Suzanne Lacy’s words, “new genre public art” is “visual art that uses both traditional and non traditional media to communicate and interact within a broad and diversified audience about issues directly relevant to their life”.[13] Her position implies pondering over the conditions of commissioning public art, the relation to its users and, to a larger extent, a divergent interpretation of the role of the audience. In the Institutional critique practice of artists such as Hans Haacke (since the 1970s) and Fred Wilson (since the 1980s), the work’s publicness corresponds to making visible for the public opinion and in the public sphere controversial public issues such as discriminatory museum policies or illegal corporation acts.

Making visible issues of public concern in the public sphere is also at the basis of the anti-monument philosophy, whose target is mining the ideology of official history. On the one hand, introducing intimate elements in public spaces normally devoted to institutional narratives, such as in the work of Jenny Holzer,[14] Alfredo Jaar’s project Es usted feliz? / Are you happy?[15] and Felix Gonzales-Torres’ billboard images.[16] On the other, through pointing at the incongruities of existing public sculptures and memorials, such as in Krzysztof Wodiczko’s video projections onto urban monuments, or in the building of counter-monuments (1980s) and Claes Oldenburg’s Lipstick (Ascending) on Caterpillar Tracks (1969-1974), a giant hybrid pop object – a lipstick – which base is a caterpillar track. Commissioned by the association of architecture students of the Yale University, the latter is a large-scale sculpture situated in the campus in front of the memorial to World War I. In 1982, Maya Lin, at the time a senior student in Architecture at Yale, completed the construction of Vietnam Veterans Memorial, listing 59’000 names of American citizens who died in the Vietnam war. Lin chooses for this work to list the names of the dead without producing any images to illustrate the loss, if not by the presence of a cut – like an injury – in the installation site floor. The cut and the site / non-site logics will stay as a recurrent image in contemporary memorials since the 1990s.[17]

Another memorial strategy is to focus on the origin of the conflict responsible for the casualties: in this line, Robert Filliou proposes, in his Commemor (1970), to have European countries exchange their memorials; Esther Shalev-Gerz and Jochem Gertz built a Memorial against Fascism (1983) in the German city of Hamburg. Others, such as Thomas Hirschhorn, build, in collaboration with local communities, precarious anti-monuments devoted to thinkers such as Spinoza (1999), Gilles Deleuze (2000) and Georges Bataille (2002).

Curated public art projects

In this line, in 1990 artist Francois Hers and mediator Xavier Douroux inaugurate the “Nouveaux commanditaires” protocol, based on the principle that the commissioner is the community of users that, in collaboration with a curator-mediator, work at the context of the project with the artist. The Nouveaux commanditaires project[18] extends the idea of site-specificness in public art to one of community-based, therefore implying the necessity of a “curated” connection between the practices that produce the community space and the artistic intervention. This is the context of the experience of doual'art project in Douala (Cameroon, 1991), based on a commissioning system that brings together the community, the artist and the commissioning institution in the realization of the project.

On the other side, the notion of “site-specific” is revisited in the 1990s in the light of the dissemination of curated public art programs attached to biennials and other cultural events. Two events in particular set the contextual and theoretical background of subsequent public art programs: Places with a Past;[19] On Taking on a Normal Situation and Re-translating it into overlapping and multiple readings of conditions past and present.[20] The first one, Places with a Past, attempts to test the juxtaposition of “city sites and sculpture” in a project-oriented curatorial context. Similarly, On Taking on… establishes a connection between site-specificity and a project-oriented culture,[21] but at the same time it programmatically bridges, already in the title, different urban and historical realities and narratives with new modes of artistic interventions. While On Taking on… acts at the same time on the site-specificity of the artistic intervention and of the exhibition, Places with a Past revisits and renews the trend of public art collections in a museum without walls fashion. This latter point will develop during the 1990s and the years 2000s, in coincidence with the dissemination of biennials and cultural events and as a consequence of city marketing strategies in the context of the “Bilbao effect” and the “destination culture” emerging after the opening of the Guggenheim museum in Bilbao.

A specific trend in urban collections of public art develops in connection with new policies in public lighting. Asia and the world's tallest mural, by German artist Hendrik Beikirch, showcases a monochromatic palette of a fisherman representing a significant portion of Korea's population.[22] It was organized by Public Delivery and painted in Busan, Korea in 2013.[23]

Online documentation

Online databases of local and regional public art emerged in the 1990s and 2000s. Aside from electronic archives at national libraries (such as the Smithsonian American Art Museum's Archives of American Art), online public art databases are usually specific to individual cities or public agencies (such as transit authorities) and are therefore geographically limited.

Other online database efforts have focused on particular public art forms, such as sculptures or murals. From 1992-1994, Heritage Preservation[24] funded the survey project Save Outdoor Sculpture!, whose acronym SOS! references the international Morse code distress signal, "SOS". This project documented more than 30,000 sculptures in the United States. The records of this survey and much more are available in the SIRIS database.[25]

Starting in 2009, WikiProject Public art has worked to document public art around the globe. While this project received significant attention within the academic community,[26] it has mainly relied on the work of students to remain active.

On 31 August 2012, Alfie Dennen re-launched the Big Art Mob project and was given control of the project from previous administrators Channel 4. The Big Art Mob in its new incarnation shifted focus from mapping the United Kingdom's Public Art to mapping the whole world's and gained instant widespread global press.[27][28] At launch the site has over 12,000 pieces of public art mapped with over 600 new works mapped as of 05/09/2012.

Interactive public art

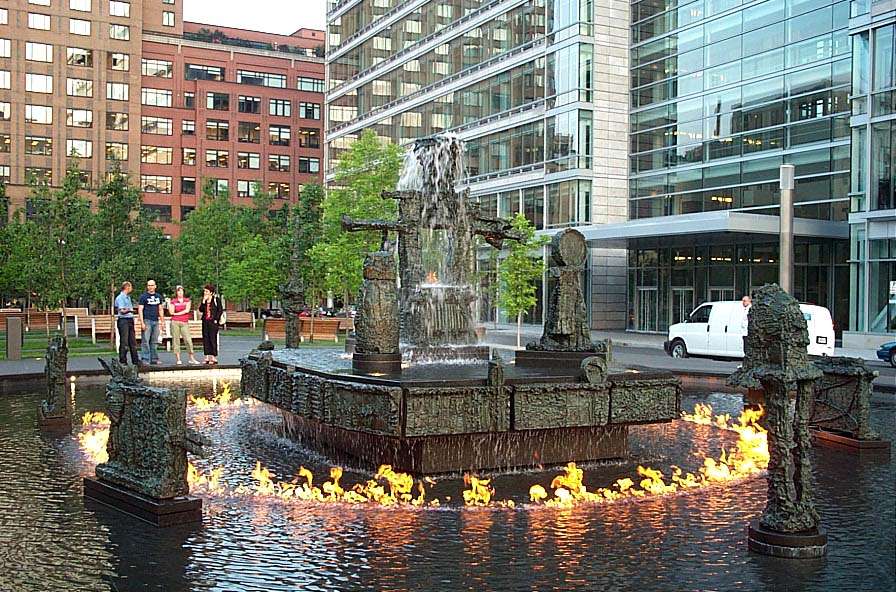

Some forms of public art are designed to encourage audience participation in a hands-on way. Examples include public art installed at hands-on science museums such as the main architectural centerpiece out in front of the Ontario Science Centre. This permanently installed artwork is a fountain that is also a musical instrument (hydraulophone) that members of the public can play at any time. The public interacts with the work by blocking water jets to force water through various sound-producing mechanisms inside the sculpture. The Federation Bells in Birrarung Marr, Melbourne is also a public art creation which works as a musical instrument. The first permanent large interactive public art was created by artist Jim Pallas in Detroit, Michigan in 1980, titled Century of Light[29], in which a large outdoor mandala of lights reacted in complex ways to sounds and movements of visitors detected by radar for 25 years until it was mistakenly destroyed.[30]

Rebecca Krinke's Map of Joy and Pain and What Needs to be Said invite public participation. In Maps visitors paint places of pleasure and pain on a map of the Twin Cities in gold and blue; in What Needs to be Said they write words and put them on a wall. Krinke is present and observes the nature of the interaction.[31] Dutch artist Daan Roosegaarde explores the nature of the public. His interactive artwork Crystal in Eindhoven can be shared or stolen. Crystal exists out of hundreds of individual salt crystals that light up when one interacts with them.[32]

From a broader framework of art and its relationship to film,[33] and the history of motion picture; additional types of 'public art' worth considering are media and film works in the digital art space.[34] According to Ginette Vincendeau and Susay Hayward, who argue in their book French Film: Texts and Contexts, taught in introduction to cinema at University of London and European Higher Education, film is indeed an art form, and goes on to argue that film is also high art.[35] Furthermore, the context of film and public spaces in the history of municipal areas and monuments may be traced back to the Father of film, Georges Méliès, as well as the Lumière brothers who invented the moving image, more commonly known as motion picture in 1896, an artistic movement that culminated in the commercialization of film industry showcased at Paris World Fair of 1900.[36]

Digital public art

Digital public art and traditional public art make use of new technologies in their creation and display. What distinguishes digital public art is its technological ability to explicitly interact with audiences.[37][38][39][40][41] These public art methodologies differ from digital community art works, (which have also been termed Socially Engaged New Media Art, or "SENMA")[42] in terms of how they establish relationships with the audience, site and outcome. In community based digital artworks these issues evolve via a dialogical process rather than as an explicit course of action, working or set of relationships.

Percent for art

Public art is usually commissioned or acquired with the authorization and collaboration of the government or company that owns or administers the space. Some governments actively encourage the creation of public art, for example, budgeting for artworks in new buildings by implementing a Percent for Art policy. Typically, one to two percent of the total cost of a city improvement project is allocated for artwork, but the amount varies widely from place to place. Administration and maintenance costs are sometimes withdrawn before the money is distributed for art (City of Los Angeles for example). Many locales have "general funds" that fund temporary programs and performances of a cultural nature rather than insisting on project-related commissions. The majority of European countries, Australia, several countries in Africa (among which South Africa and Senegal) and many cities and states in the United States, have percent for art programs. The percent for art is not applied to every capital improvement project in municipalities with percent for art policy.

The first percent-for-art legislation passed in Philadelphia in 1959. This requirement is implemented in a variety of ways. The government of Quebec maintains the art and architecture integration policy requiring the budget for all new publicly funded buildings set aside approximately 1% for artwork. New York City has a law that requires that no less than 1% of the first twenty million dollars, plus no less than one half of 1% of the amount exceeding twenty million dollars be allocated for art work in any public building that is owned by the city. The maximum allocation for any commission in New York is.[43]

In contrast, the city of Toronto requires that 1% all of construction costs be set aside for public art, with no set upper limit (although in some circumstances, the municipality and the developer might negotiate a maximum amount). In the United Kingdom percent for art is discretionary for local authorities, who implement it under the broader terms of a section 106 agreement otherwise known as 'planning gain', in practice it is negotiable, and seldom ever reaches a full 1%, where it is implemented at all. A percent for art scheme exists in Ireland and is widely implemented by many local authorities.

Arts Queensland, Australia supports a new policy (2008) for 'art + place' with a budget provided by state government and a curatorial advisory committee. It replaces the previous 'art built-in' 2005–2007. Canberra, Australia committed 1 per cent of its capital works program (including out years) from 2007 to 2009 for public art with a final amount of $778,000 being provided for in 2011-12.[44][45][46]

Public art and politics

Public art has often been used for political ends. The most extreme and widely discussed manifestations of this remain the use of art as propaganda within totalitarian regimes coupled with simultaneous suppression of dissent. The approach to art seen in Joseph Stalin's Soviet Union and Mao Zedong's Cultural Revolution in China stand as representative.

The Talking statues of Rome began a tradition of political expression in the 16th Century that still continues. Public art is also often used to refute those propagandistic desires of political regimes. Artists use culture jamming techniques, taking popular media and reinterpreting it with guerrilla-style adaptations, to comment of social and political issues relevant to the public.[1] Artists use culture jamming to facilitate social interactions around political concerns in hopes of changing the way people relate to the world by manipulating existing culture.[1] Adbusters magazine explores contemporary social and political issues through culture jamming by manipulating popular design campaigns.[47]

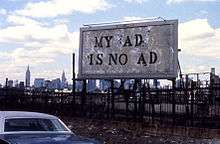

In more open societies artists often find public art useful in promoting their ideas or establishing a censorship-free means of contact with viewers. The art may be intentionally ephemeral, as in the case of temporary installations and performance pieces. Such art has a spontaneous quality. It is characteristically displayed in urban environments without the consent of authorities. In time, though, some art of this kind achieves official recognition. Examples include situations in which the line between graffiti and "guerilla" public art is blurred, such as the art of John Fekner placed on billboards, the early works of Keith Haring (executed without permission in advertising poster holders in the New York City Subway) and the work of Banksy. The Northern Irish murals and those in Los Angeles were often responses to periods of conflict.

Controversies

Public art sometimes proves controversial. A number of factors contribute to this: the desire of the artist to provoke, the diverse nature of the public, issues of appropriate uses of public funds, space, and resources, and issues of public safety.

- Detroit's Heidelberg Project was controversial due to its garish appearance for several decades since its inception in 1986.

- Richard Serra's minimalist piece Tilted Arc was removed from Foley Square in New York City in 1989 after office workers complained their work routine was disrupted by the piece. A public court hearing ruled against continued display of the work.

- Victor Pasmore's Apollo Pavilion in the English New Town of Peterlee has been a focus for local politicians and other groups complaining about the governance of the town and allocation of resources. Artists and cultural leaders mounted a campaign to rehabilitate the reputation of the work with the Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art commissioning artists Jane and Louise Wilson to make a video installation about the piece in 2003.

- House, a large 1993–94 work by Rachel Whiteread in East London, was destroyed by the local council after a few months. The artist and her agent had only secured temporary permission for the work.

- Pierre Vivant's Traffic Light tree near Canary Wharf, also in East London, caused some confusion from motorists when constructed in 1998, some of whom believed them to be real traffic signals. However, once the piece became more famous, it was voted the favourite roundabout in the country by a survey of Britain's motorists.

- Maurice Agis' Dreamspace V, a huge inflatable maze erected in Chester-le-Street, County Durham, killed two women and seriously injured a three-year-old girl in 2006 when a strong wind broke its moorings and carried it 30 ft into the air, with thirty people trapped inside.[48]

- 16 Tons, Seth Wulsin's vast 2006 work includes the demolition of the raw material it works with, a former jail in Buenos Aires. In order to gain authorization to carry out the project, Wulsin had to engage a network of local, city and national government agencies, as well as former prisoners of the jail, human rights groups, and the military.[49]

Sustainability

Public art faces a design challenge by its very nature: how best to activate the images in its surroundings. The concept of “sustainability” arises in response to the perceived environmental deficiencies of a city. Sustainable development, promoted by the United Nations since the 1980s, includes economical, social, and ecological aspects. A sustainable public art work would include plans for urban regeneration and disassembly. Sustainability has been widely adopted in many environmental planning and engineering projects. Sustainable art is a challenge to respond the needs of an opening space in public.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Knight, Cher Krause (2008). Public Art: theory, practice and populism. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4051-5559-5.

- ↑ Rafael Schacter, "The World Atlas of Street Art and Graffiti", September, 2013; ISBN 9780300199420.

- ↑ http://www.brooklynstreetart.com Rafael Schacter and His "World Atlas of Street Art and Graffiti."

- ↑ http://www.lataco.com Interview with Rafael Schacter, Author of The World Atlas of Street Art and Graffiti.

- ↑ https://www.nytimes.com Aerosol Art ("...in favor of the catchall 'Independent Public Art'").

- ↑ http://www.filippominelli.com Filippo Minelli "Silence/Shapes."

- ↑ https://www.youtube Gravity Glue 2015; (Underwater Rock balance at 3:55).

- ↑ Mary E. O’Leary (July 11, 2010). "Stored away for decades, artifacts from New Haven Arena coming back". New Haven Register. Archived from the original on September 10, 2012. Retrieved 2010-10-19.

They also cast the arch by sculptor Gar Waterman that straddles Wooster Street, the seagrass fence behind the Shubert Theatre in Temple Plaza, the iron railing around the fountain on the city Green and the owl that sits on top of Engleman Hall at Southern Connecticut State University.

- ↑ Brett Bailey, former Curator, Infecting the City Festival

- ↑ Rosalind Krauss, “Sculpture in the Expanded Field”, in: October, vol. 8, spring 1979, pp. 30-44

- ↑ 1969, Kunsthalle Bern, Switzerland, curated by Harald Szeemann

- ↑ Plastik, in Zurich, Switzerland, 1931, and Brookgreen Gardens, 1932, South Carolina

- ↑ Suzanne Lacy, ed., Mapping the Terrain: New Genre Public Art, Bay, Seattle (WA) 1995

- ↑ 1970s to present – collections of detourné common place sentences printed on billboards, projected on building façades, or screened on electronic message boards.

- ↑ 1980, dissemination of the question “Are you happy?” in the press, public clocks and billboards in different locations in Santiago, Chile.

- ↑ Beginning of the 1990s.

- ↑ See the double-negative structure of memorials to the Holocaust victims by Peter Eisenman in Berlin, in 2004, and Rachel Whiteread in Vienna, in 2000; and the cuts in Daniel Liebeskind Jewish museum in Berlin, 2001 and in Doris Salcedo’s intervention at Tate Modern, in 2007.

- ↑ nouveauxcommanditaires.eu

- ↑ Charleston, 1991, curated by Mary Jane Jacob.

- ↑ 1993, Antwerp, curated by Yves Apetitallot, Iwona Blazwick and Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, on the occasion of the Antwerp European Cultural Capital program.

- ↑ See also Sonsbeek in Arnheim, 1993 and Projet Unité, an exhibition organized at Le Corbusier public housing building in Firminy, 1993.

- ↑ Costas Voyatzis (2012-09-10). "Asia's Tallest Mural by Hendrik Beikirch". Yatzer. Retrieved 2014-07-26.

- ↑ "Asia's tallest mural – By Hendrik Beikirch". Publicdelivery.org. 2012-09-05. Retrieved 2014-07-26.

- ↑ heritagepreservation.org

- ↑ http://sirismm.si.edu/siris/ariquickstart.htm

- ↑ Mary Helen, Miller (4 April 2010). "Scholars Use Wikipedia to Save Public Art From the Dustbin of History". The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved 16 October 2010.

- ↑ All Things Considered (2012-08-23). "Big Art Mob interview". Npr.org. Retrieved 2014-07-26.

- ↑ http://www.publico.pt/Cultura/big-art-mob-um-mapa-interactivo-da-arte-de-rua-para-todo-o-mundo-1561507

- ↑ http://jpallas.com/COL/JPCENLIG.HTM

- ↑ https://www.mitpressjournals.org/doi/abs/10.1162/LEON_a_01151

- ↑ "Interview with Rebecca Krinke". Ias.umn.edu. 2012-10-01. Retrieved 2014-07-26.

- ↑ "Interview with Daan Roosegaarde at Design INDABA". Designindaba.com. 2013-01-11. Retrieved 2014-07-26.

- ↑ Film as Art by Rudolf Arnheim. (University of California Press, 1957).

- ↑ French Cinema, A Student’s Guide by Phil Powrie and Keith Reader (Bloomsbury, 2002).

- ↑ French Film: Texts and Contexts ed. by Ginette Vincendeau and Susan Hayward (Routledge, 2000).

- ↑ How to Read a Film: Movies, Media, Multimedia by James Monaco (Oxford University Press, 2000).

- ↑ "Digital Public Art". Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- ↑ Cartiere, S; Willis (2008). The practice of public art. Routledge. p. 96.

- ↑ Rafael Lozano-Hemmer,UnderScan (2005).

- ↑ Flores, T (2009). "Rafael Lozano-Hemmer: The Historical (Self-) Consciousness'". Art Nexus. 7.

- ↑ https://www.youtube.com Life in a Day project.

- ↑ Carpenter, Ele (2008). "Politicised Socially Engaged Art and New Media Art". Unpublished (PHD) Thesis.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2007-10-13. Retrieved 2007-09-04.

- ↑ Colley, Clare (28 December 2014). "Public art schemes leave costly repair bill for ACT government". The Canberra Times. Fairfax Media. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ↑ Doherty, Megan (28 April 2012). "Libs claim arts habit costs ACT $4300 a day". The Canberra Times. Fairfax Media. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ↑ Ridgely, Lisa (24 August 2011). "Canberra Confidential - A pause on public art". CityNews.com.au. Macquarie Publishing Pty Limited. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ↑ "Adbusters". Retrieved 20 April 2014.

- ↑ Stokes, Paul (24 July 2006). "Women killed as artwork floats off". The Daily Telegraph. London.

- ↑ "Página/12 :: espectaculos". Pagina12.com.ar. Retrieved 2014-07-26.

Bibliography

- The Everyday Practice of Public Art: Art, Space, and Social Inclusion, edited by Cameron Cartiere and Martin Zebracki. Routledge, 2016.

- Herlyn/Manske/Weisser: "Kunst im Stadtbild - Von Kunst am Bau zu Kunst im öffentlichen Raum", Katalog zur gleichnamigen Ausstellung in der Universität Bremen, Bremen 1976

- Ronald Kunze: Stadt, Umbau, Kunst: Sofas und Badewannen aus Beton in: STADTundRAUM, H. 2/2006, S. 62-65

- Florian Matzner (ed.): Public Art. Kunst im öffentlichen Raum, Ostfildern 2001

- Volker Plagemann (ed.): Kunst im öffentlichen Raum. Anstöße der 80er Jahre, Köln 1989

- Chris van Uffelen: 500 x Art in Public: Masterpieces from the Ancient World to the Present. Braun Publishing, 1. Auflage, 2011, 309 S., in Engl. [Mit Bild, Kurzbiografie und kurzer Beschreibung werden 500 Künstler mit je einem Kunstwerk im öffentlichen Raum vorgestellt. Alle Kontinente (außer der Antarktis) und alle Kunststile sind vertreten.]

- Federica Martini, Public Art in Mobile A2K Methodology guide, 2002.

- One Place After Another, Miwon Kwon. MIT Press, 2003.

- Public Artopia: Art in Public Space in Question, Martin Zebracki. Amsterdam University Press, 2012.

- Public Art by the Book, edited by Barbara Goldstein. 2005.

- Dialogues in Public Art, edited by Tom Finkelpearl. MIT Press, 2000.

- The Interventionists: Users' Manual for the Creative Disruption of Everyday Life, edited by Nato Thompson and Gregory Sholette. MASS MoCA, 2004.

- Conversation Pieces: Community + Communication in Modern Art, Grant Kester. University of California Press, 2004.

- Mapping the Terrain: New Genre Public Art, edited by Suzanne Lacy. Bay Press, 1995.

- Evictions: Art and Spatial Politics, Rosalyn Deutsche. MIT Press, 1998.

- In/Different Spaces: Place and Memory in Visual Culture, Victor Burgin. University of California Press, 1996.

- Art, Space and the City: Public Art and Urban Futures, Malcolm Miles. 1997.

- Spirit Poles and Flying Pigs: Public Art and Cultural Democracy in American Communities, Erika Lee Doss. 1995

- Critical Issues in Public Art: Content, Context, and Controversy, Harriet Senie and Sally Webster. 1993.

- Public Art Review, Forecast Public Art. Bi-Annual publication

- On the Museum's Ruins, Douglas Crimp. MIT Press, 1993.

- Art For Public Places: Critical Essays, by Malcolm Miles et al. 1989.

- Marching Plague: Germ Warfare and Global Public Health, Critical Art Ensemble. Autonomedia, 2006.

- The Lansing Area Arts Attitude Survey, by Suzanne Love and Kim Dammers. Michigan State University Center for Urban Affairs, 1978?

- Outdoor Monuments of Manhattan: A Historical Guide, by Dianne Durante. New York University Press, 2007

- Monument Wars: Washington, DC, the National Mall, and the Transformation of the Memorial Landscape, Kirk Savage. University of California Press, 2009

- Public Art Dialogue, Routledge, Taylor & Francis, Bi-Annual publication

- Temporary Art and Public Place: Comparing Berlin with Los Angeles, by John Powers, European University Studies, Peter Lang Publishers, 2009

- Public Art, Art & Design, Academy Group Ltd, London, 1996

External links

| Library resources about Public art |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Public art. |