Italian Spring Offensive

The Italian Spring Offensive, also known as Operazione Primavera (Operation Spring), was an offensive of the Greco-Italian War that lasted from 9 to 16 March 1941. The offensive was the last Italian attempt of the war to defeat the Greek forces, which had already advanced deep into Albanian territory.[2] The opening of the offensive was supervised by the Italian dictator Benito Mussolini but ended a week later in complete failure.[3][4][5]

Background

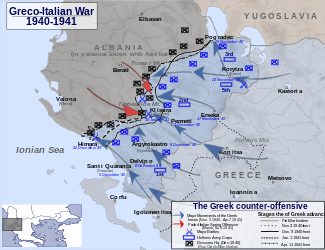

On 28 October 1940, Fascist Italy declared war upon Greece. The Italian 9th Army and 11th Army invaded north-west Greece from Albania. They were soon pushed back and the Greek army launched a counter-attack deep into Albanian territory.[6] In February 1941, intensive preparations to strengthen the Italian front line began. By the end of the month, the 15 Italian divisions fighting in Albania had been reinforced by an additional ten divisions. In order to raise the morale of the soldiers, Benito Mussolini ordered the units to be accompanied by the most aggressive fascist cadres and also by government ministers and high-ranking officials.[7]

Operations

The operation was to be directed and observed by Mussolini, who arrived in Tirana on 2 March 1941; Italian radio announced that Mussolini lead the Italian attack.[7][8] Operazione Primavera, the spring offensive began on 9 March, under General Carlo Geloso and started with heavy bombardment of Greek positions by artillery and aircraft.[9][7] Eleven infantry divisions attacked with the support of the 131st Armoured Division Centauro.[10]

The attack was mainly directed against the 1st, 2nd, 5th, 11th, 15th and 17th divisions of the Greek army and was followed by repeated infantry assaults between the rivers Osum and Vjosë, an area dominated by Trebeshinë.[10] On 14 March, Italian General Ugo Cavallero, realizing that the attacks had failed, advised Mussolini to stop the offensive.[11] Fierce fighting occurred on height 731, which was assaulted by the Italians at least 18 times. The Greek forces maintained an active defence, which included counter-attacks and systematic exploitation of advantageous terrain. Decisive factors in the Greek success were that Greek artillery was not neutralized and the high morale of the Greek troops.[7]

Aftermath

After the Italian failure the Germans could no longer expect any appreciable support from their Italian allies when they marched against Greece, since Greek forces were only 16 kilometres (10 mi) away from the strategic port of Vlorë.[5][12] With the German intervention and the subsequent capitulation of Greece in April 1941, the sector around height "731" was proclaimed a holy area by the Italians and a monument was erected by them, due to the heavy casualties they suffered.[7]

Although it failed, the Spring Offensive further exhausted the Greeks and "revealed a chronic shortage of arms and equipment" in the Greek Army, which had been fighting a much larger power continuously for the past six months.[13] The Greeks were, in the words of Stockings and Hancock, "rapidly approaching the end of their logistical tether,"[14] despite significant British material support in previous months. Following the offensive, the Greek Army as a whole possessed only a single month's supply of heavy artillery ammunition and insufficient supplies to equip its reserves; requests were immediately sent to their British allies for millions of artillery shells and tens of millions of rifle rounds. This proved to be a logistical impossibility for the British.[15]

After German intervention ensured a quick Axis victory, Hitler later acknowledged that the German invasion of Greece was greatly facilitated by the Italians holding down and bleeding white, the greater part of Greece's limited military forces.[16] In fact, Hitler would never leave his war partner, Fascist Italy, to be defeated in the war against Greece, so he issued orders for Third Reich's military intervention (Operation Marita), already from December 1940.[17]

Footnotes

- ↑ Brewer, David (28 Feb 2015). Greece, the Decade of War: Occupation, Resistance and Civil War. I.B.Tauris & Co. Ltd. p. 13. ISBN 9781780768540.

- ↑ Zapantis 1982, pp. 428–584.

- ↑ Keegan & Mayer 1977, p. 600.

- ↑ Electris & Lindsay 2008, p. 187.

- 1 2 Zapantis 1987, p. 54.

- ↑ Dear & Foot 2001, p. 600.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Sakellariou 1997, pp. 395–398.

- ↑ Zōtos 1967, p. 39.

- ↑ Cruickshank 1976, p. 130.

- 1 2 Manchester 1994, p. 146.

- ↑ Chatzēpateras et al. 1995, p. 146.

- ↑ Gervasi 1975, p. 273.

- ↑ Stockings, Craig; Hancock, Eleanor (2013). Swastika over the Acropolis: Re-interpreting the Nazi Invasion of Greece in World War II. Leiden: BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-25459-6. Page 81.

- ↑ Ibid, p. 82

- ↑ Ibid, p. 81-82; 122

- ↑ Sadkovich, Dr. J. The Italo-Greek war in context, p.458

- ↑ Mazower, Mark (1995). Inside Hitler's Greece: The Experience of Occupation, 1941-44. Yale University Press. p. 15. ISBN 9780300065527.

References

- Chatzēpateras, Kōstas N.; Maria S., Phaphaliou; Leigh Fermor, Patrick (1995). Greece 1940–41 Eyewitnessed. Athens: Efstathiadis Group. ISBN 978-960-226-533-8.

- Cruickshank, Charles Greig (1976) [1975]. Greece, 1940–1941. London: Davis-Poynter. ISBN 0-70670-180-1.

- Dear, I.; Foot, M. R. D. (2001). The Oxford companion to World War II. London: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-860446-4.

- Electris, Theodore; Lindsay, Helen (2008). Written on the Knee: A Diary from the Greek-Italian Front of WWII. Minneapolis, MN: Scarletta Press. ISBN 978-0-9824584-4-0.

- Gervasi, Frank (1975). Thunder over the Mediterranean. New York: McKay. ISBN 978-0-679-50508-2.

- Keegan, John; Mayer, Sydney L. (1977). The Rand McNally Encyclopedia of World War II. Chicago: Rand McNally. ISBN 0-52881-060-X.

- Manchester, Richard B. (1994). Incredible Facts: The Indispensable Collection of True Life Facts and Oddities. New York: BBS Publishing Corporation. ISBN 978-0-88365-708-9.

- Sakellariou, M. V. (1997). Epirus, 4000 years of Greek history and civilization. Ekdotike Athenon. ISBN 978-960-213-371-2.

- Zapantis, Andrew L. (1982). Greek-Soviet relations, 1917–1941. East European Monographs. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-88033-004-6.

- Zapantis, Andrew L. (1987). Hitler's Balkan Campaign and the Invasion of the USSR. Eastern European Monographs. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-88033-125-8.

- Zōtos, Stephanos (1967). Greece: The Struggle for Freedom. New York: Crowell. OCLC 712510.

Further reading