Internet in Cuba

The internet in Cuba stagnated since its introduction in the late 1990s because of lack of funding[2], tight government restrictions[3], and the U.S. embargo, especially the Torricelli Act[2][4]. Starting in 2007 this situation began to slowly improve.

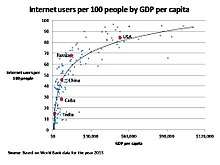

In 2015, the Cuban government opened the first public wi-fi hotspots in 35 public locations. It also reduced prices and increased speeds for internet access at state-run cybercafes. As of July 2016 4,334,022 people (38.8% of the total population) were Internet users.[5]

By January 2018, there were public hotspots in approximately 500 public locations nationwide providing access in most major cities,[6] and the country relies heavily on public infrastructure whereas home access to the Internet remains largely inaccessible for the general population. As of January 2018 mobile Internet remains inaccessible in the country, but the state plans to start offering it in 2018.[7]

History

In September 1996, Cuba's first connection to the Internet, a 64 kbit/s link to Sprint in the United States, was established.[8] After this initial introduction, the expansion of Internet access in Cuba has stagnated. Despite a lack of consensus on the exact reasons, the following appear to be major factors:

- Lack of funding, owing to the poor state of the Cuban economy after the fall of the Soviet Union and the Cuban government's fear that foreign investment would undermine national sovereignty (in other words, foreign investors putting Cuba up for sale).[2][3]

- The U.S. embargo, which delayed construction of an undersea cable, and made computers, routers, and other equipment expensive and difficult to obtain.[2]

- According to Boris Moreno Cordoves, Deputy Minister of Informatics and Communications, the Torricelli Act (part of the United States embargo against Cuba) identified the telecommunications sector as a tool for subversion of the 1959 Cuban Revolution, and the necessary technology has been conditioned by counter-revolutionaries. The internet is also seen as essential for Cuba’s economic development.[4]

The political situation in both Cuba and the United States is, however, slowly changing. In 2009, President Obama announced that the United States would allow American companies to provide Internet service to Cuba, and U.S. regulations were modified to encourage communication links with Cuba.[2] The Cuban government rejected the offer, however, preferring to work instead with the Venezuelan government.[9] In 2009 a U.S. company, TeleCuba Communications, Inc., was granted a license to install an undersea cable between Key West, Florida and Havana, although political considerations on both sides prevented the venture from moving forward.[2]

Status

Cuba’s domestic telecommunications infrastructure is limited in scope and is only appropriate for the early days of the internet. There is virtually no broadband internet access in Cuba. Cuba’s mobile network is limited in its coverage, and uses “second generation” technology, suited to voice conversations and text messaging, but not Internet applications.[2] Telecommunications between Cuba and the rest of the world is limited to the Intersputnik system and aging telephone lines connecting with the United States. Total bandwidth between Cuba and the global internet is just 209 Mbit/s upstream and 379 downstream.[2]

About 30 percent of the population (3 million users, 79th in the world) had access to the internet in 2012.[10] Internet connections are through satellite leading the cost of accessing the internet to be high.[11] The average cost of a one-hour cybercafé connection is about $0.50 (U.S.) for the national network and $1.00 (U.S.) for the international network, while the average monthly salary is just $20 (U.S.).[11] Private ownership of a computer or cell phone required a difficult-to-obtain government permit until 2008.[12] Owing to limited bandwidth, authorities give preference to use from locations where Internet access is used on a collective basis, such as in work places, schools, and research centers, where many people have access to the same computers or network.[13]

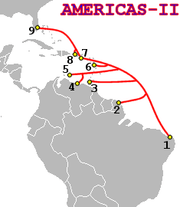

A new undersea fiber-optic link to Venezuela (ALBA-1) was scheduled for 2011.[14][15] The fiber-optic cable linking Cuba to Jamaica and Venezuela arrived In February 2011; it was expected to provide download speeds up to 3000 times faster than previously available.[16][17] The fiber-optic cable was expected to be in operation by the summer of 2011, but reports in October 2011 stated that it was not yet in place. The government has not commented on the issue, which has led citizens to believe that the project was never completed, owing to corruption in the Cuban government.[18] In May 2012 there were reports that the cable was now operational, but with its use restricted to Cuban and Venezuelan government entities. Internet access by the general public still used the slower and more expensive satellite links[19] until January 2013, when Internet speeds increased.[20]

One network link connects to the global Internet and is used by government officials and tourists, while another connection for use by the general public has restricted content. Most access is to a government-controlled national intranet and an in-country e-mail system.[21] The intranet contains the EcuRed encyclopedia and websites that are supportive of the government. Such a network is similar to the Kwangmyong used by North Korea, a network Myanmar uses and a network Iran has plans to implement.[22]

Starting on 4 June 2013 Cubans can sign up with ETECSA, the state telecom company, for public Internet access under the brand "Nauta" at 118 centers across the country.[23] The Juventud Rebelde, an official newspaper, said new areas of the Internet would gradually become available.

In early 2016, ETEC S.A. began a pilot program for broadband Internet service in Cuban homes, with a view to rolling out broadband Internet services in private residences.[24] And there are approximately 250 WiFi hotspots around the country.

In mid December 2016 Google and the Cuban government signed a deal allowing the internet giant to provide faster access to its data by installing servers on the island that will store much of the company's most popular content. Storing Google data in Cuba eliminates the long distances that signals must travel from the island through Venezuela to the nearest Google server.[25]

As of May 2018 the cost of Internet access is CUC$1.00 per hour (or CUC$0.10 for domestic intranet access), which is still high in a country where state salaries average $20 a month.[26] [27]

Future prospects

Availability and use of the Internet in Cuba is slowly changing. There is a good deal of pent up demand among the well-educated Cuban population. When buying computers was legalized in 2008, the private ownership of computers in Cuba soared (there were 630,000 computers available on the island in 2008, a 23% increase over 2007).[13]

China, Cuba's second largest trading partner and the largest importer of Cuban goods, has pledged to "provide assistance to Cuba to help its social and economic development." Chinese networking equipment and expertise are world class and China has experience building domestic communication infrastructure in developing nations.[2]

As Cuba advances its economy into the 21st century, informatics will play an increasingly important role.[28]

SNET

SNET (abbreviated from Street Network) is a Cuban grassroots wireless community network which allows people to play games or pirate movies by using interconnected network of households.[29][30][31]

Censorship

Cuba has been listed as an "Internet Enemy" by Reporters Without Borders since the list was created in 2006.[11] The level of Internet filtering in Cuba is not categorized by the OpenNet Initiative due to lack of data.[32]

References

- ↑ TECNOLOGÍA DE LA INFORMACIÓN Y LAS COMUNICACIONES EN CIFRAS. CUBA 2011 de la Oficina Nacional de Estadística e Información, Enero-Diciembre de 2011

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 The state of the Internet in Cuba, January 2011, Larry Press, Professor of Information Systems at California State University, January 2011

- 1 2 (in Spanish) "Encuentro con el Canciller Bruno Rodríguez y la agenda de diálogo de CAFE" Archived 2013-08-22 at the Wayback Machine. ("Meeting with Foreign Minister Bruno Rodriguez and the dialogue agenda CAFE"), 2 October 2012, accessed 25 May 2013. (English translation)

- 1 2 Juventud Rebelde (6 February 2009), Internet es vital para el desarrollo de Cuba (Internet is vital for the development of Cuba) (in Spanish), Cuban Youth Daily (English translation)

- ↑ "The World Factbook — Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov. Retrieved 2018-01-03.

- ↑ "Cubans to gain access to mobile internet in 2018 - Xinhua | English.news.cn". www.xinhuanet.com. Retrieved 2018-01-06.

- ↑ Press, Europa (2018-01-03). "Internet móvil llega a Cuba este 2018". notimerica.com (in Spanish). Retrieved 2018-01-06.

- ↑ Larry Press (27 February 2011), Cuba's first Internet connection, The Internet in Cuba@blogspot.com

- ↑ "Wired, at last". The Economist. 3 March 2011.

- ↑ "Percentage of Individuals using the Internet 2000-2012", International Telecommunications Union (Geneva), June 2013, retrieved 22 June 2013

- 1 2 3 "Internet Enemies: Cuba" Archived 2011-05-17 at the Wayback Machine., Reporters Without Borders, March 2011

- ↑ "Changes in Cuba: From Fidel to Raul Castro", Perceptions of Cuba: Canadian and American policies in comparative perspective, Lana Wylie, University of Toronto Press Incorporated, 2010, p. 114, ISBN 978-1-4426-4061-0

- 1 2 "Cuba to keep internet limits". Agence France-Presse (AFP). 9 February 2009.

- ↑ Undersea cable to bring fast internet to Cuba, The Telegraph (UK), 24 January 2011

- ↑ Andrea Rodriguez (9 February 2011), Fiber-Optic Communications Cable Arrives In Cuba, Huffington Post

- ↑ Marc Frank; Kevin Gray; Eric Walsh (7 July 2011). "Cuban cellphones hit 1 million, Net access lags". Reuters. Retrieved 6 November 2011.

- ↑ Biddle, Ellery Roberts (19 November 2010). "Cuba: Fiber Optic Cable May Not Bring Greater Internet Access". Global Voices. Retrieved 6 November 2011.

- ↑ Padura, Leonardo (October 2011). "Cuba: What's Delivered and What Isn't". Inter Press Service (IPS). Archived from the original on 2011-10-12.

- ↑ "Fiber-optic cable benefiting only Cuban government", Miami Herald, 25 May 2012

- ↑ Marc Frank (22 January 2013). "Cuba's mystery fiber-optic Internet cable stirs to life". Havana. Reuters. Retrieved 26 January 2013.

- ↑ "Country report: Cuba", World Factbook, U.S. Central Intelligence Agency, 27 September 2011

- ↑ Christopher Rhoads and Farnaz Fassihi, May 28, 2011, Iran Vows to Unplug Internet, Wall Street Journal

- ↑ del Valle, Amaury E. (27 May 2013). "Cuba amplía el servicio público de acceso a Internet" [Cuba expands public service Internet access]. Juventud Rebelde (in Spanish).

- ↑ "Cuba says it will launch broadband home internet project". Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- ↑ "Google has signed a deal to bring faster internet speeds to Cuba". Business Insider. 13 December 2013.

- ↑ "ETECSA, Internet y conectividad Internet". Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- ↑ "Centers in Cuba Will Offer High-Priced Access to Web". The New York Times. AP. 13 December 2013.

- ↑ "Havana's top IT authority discusses Cuba's internet future". Cuba Trade Magazine. 1 June 2017.

- ↑ Crecente, Brian (2017-05-15). "Inside Cuba's secretive underground gamer network". Polygon. Retrieved 2018-01-03.

- ↑ Martínez, Antonio García. "Inside Cuba's DIY Internet Revolution". WIRED. Retrieved 2018-01-03.

- ↑ Estes, Adam Clark. "Cuba's Illegal Underground Internet Is Thriving". Gizmodo. Retrieved 2018-01-03.

- ↑ "ONI Country Profile: Cuba", OpenNet Initiative, May 2007

Further reading

- Tamayo, Juan O. "Cuba’s new Internet locales remain conditioned." Miami Herald. June 6, 2013.

- Baron, G. and Hall, G. (2014), Access Online: Internet Governance and Image in Cuba. Bulletin of Latin American Research. doi: 10.1111/blar.12263

External links

- "Internet politics in Cuba", Carlos Uxo, La Trobe University, Telecommunications Journal of Australia, Vol. 60, No. 1 (February 2010)

- Article on the state of the Internet in Cuba, "An Internet Diffusion Framework", by Larry Press, Grey Burkhart, Will Foster, Seymour Goodman, Peter Wolcott, and Jon Woodard, in Communications of the ACM, Vol. 41, No. 10, pp 21–26, October, 1998

- "Cuban bibliography", lists fourteen reports and articles on the Internet in Cuba from 1992 to 1998, by Larry Press, Professor of Information Systems at California State University

- "Internet in Cuba" Thousands of articles about and referring to the Internet in Cuba.

- Public places with Wi-Fi access provided by ETECSA (Empresa de Telecomunicaciones de Cuba S.A.) in Spanish.

- Wifi Nauta hotspots in Cuba a comprehensive lists of Nauta hotspots in Cuba (in Spanish).

- La Red Cubana—a blog on Cuban Internet technology, policy and applications (in English).

- OFFLINE a documentary about the lack of internet in Cuba. From Cuba by Yaima Pardo. (Video) (English CC)

- Etecsa, Internet y conectividad Internet.