Internet censorship in Cuba

Internet censorship in Cuba, while present, is not particularly extensive.[1] Evidence shows that internet censorship in Cuba mainly relies on deep packet inspection (DPI) and does not affect encrypted HTTP (HTTPS) traffic. Cuba has been listed as an "Internet Enemy" by Reporters Without Borders since the list was created in 2006.[2] The level of Internet filtering in Cuba is not categorized by the OpenNet Initiative due to a lack of data.[3]

Background

Two kinds of online connections are offered in Cuban Internet cafes: a 'national' one that is restricted to a simple e-mail service operated by the government, and an 'international' one that gives access to the entire Internet. The population is restricted to the first one, which costs €1.20 an hour. To use a computer, Cubans have to give their name and address - and if they write dissent keywords, a popup appears stating that the document has been blocked 'for state security reasons', and the word processor or browser is automatically closed. Foreign visitors who allow Cubans to use their computers are harassed and persecuted.[4]

All material intended for publication on the Internet must first be approved by the National Registry of Serial Publications. Service providers may not grant access to individuals not approved by the government.[5] One report found that many foreign news outlet websites are not blocked in Cuba, but the slow connections and outdated technology in Cuba makes it impossible for citizens to load these websites.[6] Rather than having complex filtering systems, the government relies on the high cost of getting online and the telecommunications infrastructure that is slow to restrict Internet access.[2]

Reports have shown that the Cuban government uses Avila Link software to monitor citizens use of the Internet. By routing connections through a proxy server, the government is able to obtain citizens' usernames and passwords.[6]

Cuban ambassador Miguel Ramirez has argued that Cuba has the right to "regulate access to [the] Internet and avoid hackers, stealing passwords, [and] access to pornographic, satanic cults, terrorist or other negative sites".[7]

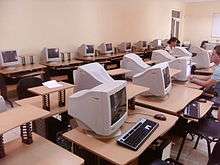

Because of limited bandwidth, authorities give preference to use from locations where Internet access is used on a collective basis, such as in work places, schools, and research centers, where many people have access to the same computers or network.[8] Authorities claim that 1,600,000 or about twelve percent of the population have access to Internet, and there were 630,000 computers available on the island in 2008, a 23% increase over 2007. But it is also seen as essential for Cuba’s economic development.[9]

Reporters Without Borders suspects that Cuba obtained some of its internet surveillance technology from China, which has supplied other countries such as Zimbabwe and Belarus. Cuba does not enforce the same level of internet keyword censorship as China.[4]

Guillermo Fariñas, a Cuban doctor of psychology, independent journalist, and political dissident, held a seven-month hunger strike to protest Internet censorship in Cuba. He ended it in the autumn of 2006, with severe health problems, although he was still conscious. He has stated that he is ready to die in the struggle against censorship.[10]

In recent times, censorship of the Internet has slowly relaxed. For example, in 2007, it became possible for members of the public to legally buy a computer.[11] Digital media is starting to play a more important role, bringing news of events in Cuba to the rest of the world. In spite of restrictions, Cubans connect to the Internet at embassies, Internet cafés, through friends at universities, hotels, and work. Cellphone availability is increasing.[12] Starting on 4 June 2013 Cubans can sign up with Etecsa, the state telecom company, for public Internet access at 118 centers across the country. Juventud Rebelde, an official newspaper, said new areas of the Internet would gradually become available. The cost of the new access at $4.50 an hour is still high in a country where state salaries average $20 a month.[13]

Alan Phillip Gross, under employment with a contractor for the U.S. Agency for International Development, was arrested in Cuba on 3 December 2009 and was convicted on 12 March 2011 for covertly distributing laptops and cellular phones on the island.[14][15][16]

The rise of digital media in Cuba has led the government to be increasingly worried about these tools; U.S. diplomatic cables published by WikiLeaks in December 2010 revealed that US diplomats believed that the Cuban government is more afraid of bloggers than of "traditional" dissidents. The government has increased its own presence on blogging platforms with the number of "pro-government" blogging platforms on the rise since 2009.[2]

Circumventing Censorship

In order to get around the government's control of the Internet, citizens have developed numerous techniques. Some get online through embassies and coffee shops or purchase accounts through the black market. The black market consists of professional or former government officials who have been cleared to have Internet access.[2] These individuals sell or rent their usernames and passwords to citizens who want to have access.[17]

Bloggers and other dissidents that have trouble getting online may use flash drives to get their work published. The blogger will type their piece on a computer, save it on a flash drive, and then hand it to another person who has an easier time getting online at a hotel or other more open venue.[2] Flash drives along with data discs are also used to distribute material (articles, prohibited photos, satirical cartoons, video clips) that has been downloaded from the Internet or stolen from government offices. Others get their work out by writing it by hand and then calling a person abroad to have them transcribe and publish it on their behalf.[6]

Bloggers such as Yoani Sánchez send text message tweets from a mobile phone.[18] Another mechanism to get tweets out is to insert a foreign SIM card into a cell phone and access the Internet through the phone.[2] Some citizens are able "to break through the infrastructural blockages by building their own antennas, using illegal dial-up connections, and developing blogs on foreign platforms."[6]

In an attempt to deliver media to the Cuban public without unreliable digital means, some Cubans have gone as far as hand delivering content to the user through the use of portable hard drives.[19] This allows individuals to avoid having to use internet circumvention tools altogether and presents a more straight forward approach to gathering content for those who are not as technically adept or do not have the resources to gather content from the internet. (E.g: individuals with slow internet speeds or antiquated computers)

References

- ↑ "OONI - Measuring Internet Censorship in Cuba's ParkNets". ooni.torproject.org. Retrieved 2018-06-27.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Internet Enemies: Cuba" Archived 2011-05-17 at the Wayback Machine., Reporters Without Borders, March 2011

- ↑ "ONI Country Profile: Cuba", OpenNet Initiative, May 2007

- 1 2 Claire Voeux and Julien Pain (October 2006). "Going online in Cuba: Internet under surveillance" (PDF). Reporters Without Borders. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-03-03.

- ↑ Azel, José (27 February 2011). "Opinion: Cuba's Internet repression equals groupthink". The Miami Herald.

- 1 2 3 4 "Cuba" (PDF). Freedom on the Net 2011. Freedom House. 4 May 2011.

- ↑ Luxner, Larry (February 2004). "Cuba delays crackdown against illegal access to Internet". Cuba News.

- ↑ "Cuba to keep internet limits". Havana: Agence France-Presse (AFP). 6 February 2009. Retrieved 7 August 2012.

- ↑ Juventud Rebelde (6 February 2009), Internet es vital para el desarrollo de Cuba (Internet is vital for the development of Cuba) (in Spanish), Cuban Youth Daily (English translation)

- ↑ "Guillermo Fariñas ends seven-month-old hunger strike for Internet access". Reporters Without Borders. 1 September 2006.

- ↑ "Changes in Cuba: From Fidel to Raul Castro", Perceptions of Cuba: Canadian and American policies in comparative perspective, Lana Wylie, University of Toronto Press Incorporated, 2010, p. 114, ISBN 978-1-4426-4061-0

- ↑ "New media bring the world closer to Cuba: Cuban bloggers and dissidents are becoming adept at sending news of protests abroad, but internal communication remains difficult", Mini Whitefield, Miami Herald, 8 October 2011 Archived October 14, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Cuban Centers to Offer a Costly Glimpse of the Web", New York Times (AP), 28 May 2013

- ↑ Shefler, Gil (13 March 2011). "Cuba sentence for Jewish aid worker draws US ire". Jerusalem Post. Reuters.

- ↑ Sanchez, Isabel (13 March 2011). "Cuba sentences US contractor amid tense ties". Agence France-Presse (AFP).

- ↑ "Alan Gross Sentenced to 15 Years in Prison". Cuban News Agency. 12 March 2011.

- ↑ "Havana Internet cafes". Havana Guide. Retrieved 7 November 2011.

- ↑ Whitefield, Mimi (5 October 2011). "New media bring the world closer to Cuba". Miami Herald. Retrieved 6 November 2011.

- ↑ Pedro, Emilio San (2015-08-10). "Cuban internet delivered by hand". BBC News. Retrieved 2018-06-27.

See also

External links

- "Internet Enemies: Cuba", Reporters Without Borders.

- "Cuba country report", Freedom on the Net 2013, Freedom House.

- "The Rule of Law and Cuba", a webpage with links to the Cuban Penal Code and Cuban Constitution in Spanish with some translations to English by the Cuba Center for the Advancement of Human Rights at Florida State University in Tallahassee, Florida USA.

- "Internet politics in Cuba", Carlos Uxo, La Trobe University, Telecommunications Journal of Australia, Vol. 60, No. 1 (February 2010).

- "Cuban bibliography", lists fourteen reports and articles on the Internet in Cuba from 1992 to 1998, by Larry Press, Professor of Information Systems at California State University.