Eileithyia

| Eileithyia | |

|---|---|

| Goddess of Childbirth | |

| |

| Abode | Mount Olympus |

| Personal information | |

| Parents | Zeus and Hera |

| Siblings | Aeacus, Angelos, Aphrodite, Apollo, Ares, Artemis, Athena, Dionysus, Enyo, Ersa, Hebe, Helen of Troy, Heracles, Hermes, Minos, Pandia, Persephone, Perseus, Rhadamanthus, the Graces, the Horae, the Litae, the Muses, the Moirai |

| Roman equivalent | Lucina |

Eileithyia or Ilithyia (/ɪlɪˈθaɪ.ə/;[1] Greek: Εἰλείθυια;,Ἐλεύθυια (Eleuthyia) in Crete, also Ἐλευθία (Eleuthia) or Ἐλυσία (Elysia) in Laconia and Messene, and Ἐλευθώ (Eleuthō) in literature)[2] was the Greek goddess of childbirth and midwifery.[3] In the cave of Amnisos (Crete) she was related with the annual birth of the divine child, and her cult is connected with Enesidaon (the earth shaker), who was the chthonic aspect of the god Poseidon. It is possible that her cult is related with the cult of Eleusis.[4]

Etymology

The earliest form of the name is the Mycenaean Greek 𐀁𐀩𐀄𐀴𐀊, e-re-u-ti-ja, written in the Linear B syllabic script.[5] Ilithyia is the latinisation of Εἰλείθυια.

The etymology of the name is uncertain. R. S. P. Beekes, suggests a not Indo-European etymology,[6] and Nilsson believes that the name is Pre-Greek.[7] 19th-century scholars suggested that the name is Greek, derived from the verb eleutho (ἐλεύθω), "to bring", the goddess thus being The Bringer.[8] Walter Burkert believes that Eileithyia is the Greek goddess of birth and that her name is pure Greek.[9] However, the relation with the Greek prefix ἐλεύθ is uncertain, because the prefix appears in some pre-Greek toponyms like Ἐλευθέρνα (Eleutherna); therefore it is possible that the name is pre-Greek.[10] Her name Ἐλυσία (Elysia) in Laconia and Messene, probably relates her with the month Eleusinios and Eleusis[11][12] Nilsson believes that the name "Eleusis" is pre-Greek[13]

Origins

According to F. Willets, "The links between Eileithyia, an earlier Minoan goddess, and a still earlier Neolithic prototype are, relatively, firm. The continuity of her cult depends upon the unchanging concept of her function. Eileithyia was the goddess of childbirth; and the divine helper of women in labour has an obvious origin in the human midwife." To Homer, she is "the goddess of childbirth".[14] The Iliad pictures Eileithyia alone, or sometimes multiplied, as the Eileithyiai:

And even as when the sharp dart striketh a woman in travail, [270] the piercing dart that the Eilithyiae, the goddesses of childbirth, send—even the daughters of Hera that have in their keeping bitter pangs;[15]

— Iliad 11.269–272

Hesiod (c. 700 BC) described Eileithyia as a daughter of Hera by Zeus (Theogony 921)[16]—and the Bibliotheca (Roman-era) and Diodorus Siculus (c. 90–27 BC) (5.72.5) agreed. But Pausanias, writing in the 2nd century AD, reported another early source (now lost): "The Lycian Olen, an earlier poet, who composed for the Delians, among other hymns, one to Eileithyia, styles her 'the clever spinner', clearly identifying her with Fate, and makes her older than Cronus."[17] Being the youngest born to Gaia, Cronus was a Titan of the first generation and he was identified as the father of Zeus. Likewise, the meticulously accurate mythographer Pindar (522–443 BC) also makes no mention of Zeus:

Goddess of childbirth, Eileithyia, maid to the throne of the deep-thinking Moirai, child of all-powerful Hera, hear my song.

— Seventh Nemean Ode

Later, for the Classical Greeks, "She is closely associated with Artemis and Hera," Burkert asserts (1985, p 1761), "but develops no character of her own". In the Orphic Hymn to Prothyraeia, the association of a goddess of childbirth as an epithet of virginal Artemis, making the death-dealing huntress also "she who comes to the aid of women in childbirth," (Graves 1955 15.a.1), would be inexplicable in purely Olympian terms:

When racked with labour pangs, and sore distressed

the sex invoke thee, as the soul's sure rest;

for thou Eileithyia alone canst give relief to pain,

which art attempts to ease, but tries in vain.

Artemis Eileithyia, venerable power,

who bringest relief in labour's dreadful hour.— Orphic Hymn 2, to Prothyraeia, as translated by Thomas Taylor, 1792.

Thus Aelian in the 3rd century AD could refer to "Artemis of the child-bed" (On Animals 7.15).

The Beauty of Durrës, a large 4th-century BC mosaic showing the head figure of a woman, probably portrays the goddess Eileithyia.[18]

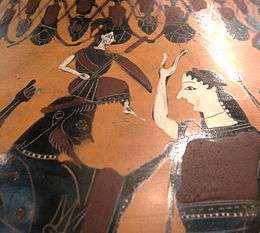

Vase-painters, when illustrating the birth of Athena from Zeus' head, may show two assisting Eileithyiai, with their hands raised in the epiphany gesture.

Cult at Amnisos

The cave of Eileithyia near Amnisos, the harbor of Knossos, mentioned in the Odyssey (xix.198) in connection with her cult, was accounted the birthplace of Eileithyia. The Cretan cave has stalactites suggestive of the goddess' double form (Kerenyi 1976 fig. 6), of bringing labor on and of delaying it, and votive offerings to her have been found establishing the continuity of her cult from Neolithic times, with a revival as late as the Roman period.[19] Here she was probably being worshipped before Zeus arrived in the Aegean, but certainly in Minoan–Mycenaean times (Burkert 1985 p 171; Nilsson 1950:53). The goddess is mentioned as Eleuthia in a Linear B fragment from Knossos. In classical times, there were shrines to Eileithyia in the Cretan cities of Lato and Eleutherna and a sacred cave at Inatos. In the cave of Amnisos (Crete) the god Enesidaon ( the "earth shaker", who is the chthonic Poseidon) is related with the cult of Eileithyia.[20] She was related with the annual birth of the divine child.[21] The goddess of nature and her companion survived in the Eleusinian cult, where the following words were uttered: "Mighty Potnia bore a strong son."[22]

On the Greek mainland, at Olympia, an archaic shrine with an inner cella sacred to the serpent-savior of the city (Sosipolis) and to Eileithyia was seen by the traveller Pausanias in the 2nd century AD (Greece vi.20.1–3); in it, a virgin-priestess cared for a serpent that was "fed" on honeyed barley-cakes and water—an offering suited to Demeter. The shrine memorialized the appearance of a crone with a babe in arms, at a crucial moment when Elians were threatened by forces from Arcadia. The child, placed on the ground between the contending forces, changed into a serpent, driving the Arcadians away in flight, before it disappeared into the hill.

There were ancient icons of Eileithyia at Athens, one said to have been brought from Crete, according to Pausanias, who mentioned shrines to Eileithyia in Tegea[23] and Argos, with an extremely important shrine in Aigion. Eileithyia, along with Artemis and Persephone, is often shown carrying torches to bring children out of darkness and into light: in Roman mythology her counterpart in easing labor is Lucina ("of the light").

In Greek shrines, small terracotta votive figures (kourotrophos) depicted an immortal nurse who took care of divine infants, who may be connected with Eileithyia. According to the Homeric Hymn III to Delian Apollo, Hera detained Eileithyia, who was coming from the Hyperboreans in the far north, to prevent Leto from going into labor with Artemis and Apollo, because the father was Zeus. Hera was very jealous of Zeus's relations with others and went out of her way to make the women suffer. The other goddesses present at the birthing on Delos sent Iris to bring her. As she stepped upon the island, the birth began.

Eileithyia was especially worshipped in Crete, in the cities Lato and doubtless, from its etymological link, Eleutherna, though no archaeological find has identified her there. Caves were sacred to her: the inescapable association to the birth canal cannot be proved beyond a skeptic's doubt. Her Egyptian counterpart is Tawaret.

Genealogy

| Eileithyia's family tree | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes

- ↑ Joseph Emerson Worcester, A comprehensive dictionary of the English language, Boston, 1871, p. 480, rule 3, where he notes the word has four syllables as in Greek and Latin, "not I-lith-y-i'-a as in Walker" (e.g. Walker and Trollope, A key to the classical pronunciation etc., London, 1830, p. 123).

- ↑ Nilsson Vol I, p. 313

- ↑ Gantz, pp. 82–83.

- ↑ F.Schachermeyer(1967).Die Minoische Kultur des alten Kreta.W.Kohlhammer Stuttgart. pp. 141–142

- ↑ "The Linear B word e-re-u-ti-ja". Palaeolexicon. Word study tool of Ancient languages. Raymoure, K.A. "e-re-u-ti-ja". Minoan Linear A & Mycenaean Linear B. Deaditerranean.

- ↑ R. S. P. Beekes, Etymological Dictionary of Greek, Brill, 2009, p. 383.

- ↑ Nilsson Vol I, p. 313

- ↑ Max Müller, Contributions to the Science of Mythology, Vol. 2, Kessinger Publishing, 2003 [1897], p. 697

- ↑ Walter Burkert (1985) Greek Religion. Harvard University Press p.26

- ↑ Nilsson, Vol I, p. 312

- ↑ "Cretan dialect 'Eleuthia' would connect Eileithyia (or perhaps the goddess "Eleutheria") to Eleusis". Willets, p. 222.

- ↑ F.Schachermeyer (1967) Die Minoische Kultur des alten Kreta W.Kohlhammer Stuttgart, p. 141

- ↑ Nilsson Vol I, p. 312

- ↑ Homer, Iliad 16.187, 19.103.

- ↑ Homer, Iliad 11.270, The plural is also used at Iliad 19.119.

- ↑ Theogony 912–923.

- ↑ Pausanias, 8.21.3.

- ↑ Bank of Albania – Coin with “The Beauty of Durrës”

- ↑ For the proceedings and findings of the archaeology, see Amnisos.

- ↑ Dietrich, pp. 220–221.

- ↑ Dietrich, p. 109.

- ↑ Dietrich, p. 167

- ↑ Pausanias, 8.48.7 .

- ↑ According to Homer, Iliad 1.570–579, 14.338, Odyssey 8.312, Hephaestus was apparently the son of Hera and Zeus, see Gantz, p. 74.

- ↑ According to Hesiod, Theogony 927–929, Hephaestus was produced by Hera alone, with no father, see Gantz, p. 74.

References

- Beekes, R. S. P., Etymological Dictionary of Greek, Brill, 2009.

- Burkert, Walter, Greek Religion, 1985.

- Gantz, Timothy, Early Greek Myth: A Guide to Literary and Artistic Sources, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996, Two volumes: ISBN 978-0-8018-5360-9 (Vol. 1), ISBN 978-0-8018-5362-3 (Vol. 2).

- Graves, Robert, The Greek Myths, 1955.

- Hesiod, Theogony, in The Homeric Hymns and Homerica with an English Translation by Hugh G. Evelyn-White, Cambridge, Massachusetts., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1914. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Homer, The Iliad with an English Translation by A. T. Murray, Ph.D., in two volumes. Cambridge, Massachusetts., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann, Ltd. 1924. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Homer; The Odyssey with an English Translation by A. T. Murray, Ph.D., in two volumes. Cambridge, Massachusetts., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann, Ltd. 1919. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Kerenyi, Karl, Dionysus: Archetypal Image of Indestructible Life, English translation 1976.

- Nilsson, Martin P. (1927) 1950. The Minoan-Mycenaean Religion and Its Survival in Greek Religion 2nd ed. (Lund"Gleerup).

- Pausanias, Pausanias Description of Greece with an English Translation by W.H.S. Jones, Litt.D., and H. A. Ormerod, M.A., in 4 Volumes. Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1918. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Willetts, R. F. "Cretan Eileithyia" The Classical Quarterly New Series, 8.3/4 (November 1958), pp. 221–223.