Achelous

In Greek mythology, Achelous (/ækɪˈloʊ.əs/; Ancient Greek: Ἀχελώїoς, and later Ἀχελῷος Achelṓios) was originally the god of all water[1] and the rivers of the world were viewed by many as his sinews.[2][3] Later, in Hellenistic times, he was mostly relegated to the Achelous River, which is the largest river of Greece, and thus the chief of all river deities, every river having its own river spirit.

Achelous was also an important deity in Etruscan mythology,[4][5] intimately related to water as in the Greek tradition but also carrying significant chthonic associations. Man-faced bull iconography was first adapted to represent Achelous by the Etruscans in the 8th century BC, and the Greeks later adopted this same tradition.[6]

Etymology

The name Ἀχελώїoς is possibly pre-Greek, its meaning not entirely certain. Recent arguments suggest it is Semitic in origin, with the initial Aχ- stemming from the Akkadian aḫu "bank of the river", or aḫû "seashore". Likewise, the Greek ending -ελώἴος probably stems from the Akkadian illu "watercourse" or "water of the river invading land", and also elu and ilu, which mean "deity".[7]

Origin

Homer placed Achelous above all, the origin of all the world's fresh water and perhaps all water.[8] By Roman times, Homer's reference was interpreted as making Achelous "prince of rivers".[9] According to Alcaeus he was the son of Gaia and Oceanus,[10] whereas Hesiod in his canonical Theogony presented Tethys and Oceanus as the parents of all three thousand river gods.[11] In the Renaissance, the improvisatory mythographer Natalis Comes made for his parents Gaia and Helios.[12]

Some derived the legends about Achelous from Egypt, and describe him as a second Nilus.[12] Herodotus compared the two rivers in their power to amass new land:

"There are other rivers as well which, though not as large as the Nile, have had substantial results. In particular (although I could name others), there is the Achelous, which flows through Acarnania into the sea and has already turned half the Echinades islands into mainland."[13]

Achelous was considered to be an important divinity throughout Greece from the earliest times,[14] and was invoked in prayers, sacrifices, on taking oaths, etc.;[15] the oracular Zeus at Dodona usually added to each oracle he gave, the command to offer sacrifices to Achelous.[16] The widespread worship of Achelous points to a more generic meaning of the god himself, perhaps accounting for an interpretation of Achelous as the representative of sweet water in general, and consequently, as the source of all nourishment.[17][12]

A recent study has tried to show that both the form and substance of Achelous, as a god of water primarily depicted as a man-faced bull, have roots in Old Europe in the Bronze Age. After the disappearance of many Old European cultures, the traditions traveled to the Near East at the beginning of 4th millennium BC (Ubaid period),[18] and finally migrated to Greece, Italy, Sicily, and Sardinia with itinerant sea-folk during the Late Bronze Age through the Orientalizing period.[19] Although no single cult of Achelous persisted throughout all of these generations, the iconography and general mythos easily spread from one culture to another, and all examples of man-faced bulls are found around the area of the Mediterraneanan, suggesting some intercultural continuity.[20] The leading exponents into the Greek and Etruscan worlds were seer-healers and mercenaries during the Iron Age, and Achelous as a man-faced bull becomes an emblem employed by mercenaries in the Greek world for centuries.[19] These earlier figures probably adapted the mythological and iconographic traditions of Asallúhi (also Asarlúhi or Asaruludu),[21][22] the "princely bison" of Near Eastern traditions that "rises to the surface of the earth in springs and marshes, ultimately flowing as rivers."[23]

Mythology

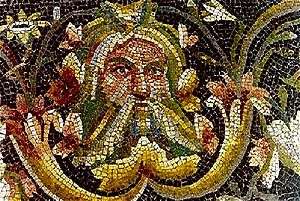

Achelous was a suitor for Deianeira, daughter of Oeneus king of Calydon, but was defeated by Heracles, who wed her himself. The contest of Achelous with Heracles was represented on the throne of Amyclae,[24] and in the treasury of the Megarans at Olympia there was a statue of him made by Dontas of cedarwood and gold.[25] Achelous was sometimes depicted as a gray-haired old man or a vigorous bearded man in his prime, with a horned head and a serpent-like body. On several coins of Acarnania the god is represented as a bull with the head of an old man.[26] The most common depiction of Achelous in Archaic and Classical times was this man-faced bull.[27] Often a city would feature a man-faced bull on its coinage to represent a local variant of Achelous, such as Achelous Gelas of Gela, Sicily, or Achelous Sebethos of Neapolis, Campania.[20]

When he battled Heracles over the river nymph Deianeira, Achelous turned himself into a serpent and a bull, which may both be seen as symbols of the chthonic realm. Heracles tore off one of his horns and forced the god to surrender. Achelous had to trade the goat horn of Amalthea to get it back.[29] Heracles gave it to the Naiads, who transformed it into the cornucopia. Achelous relates the bitter episode afterwards to Theseus in Ovid's Metamorphoses.[30] Sophocles makes Deianeira relate these occurrences in a somewhat different manner, picturing a mortal woman's terror at being courted by a chthonic river god:

- My suitor was the river Achelóüs,

- who took three forms to ask me of my father:

- a rambling bull once, then a writhing snake

- of gleaming colors, then again a man

- with ox-like face: and from his beard's dark shadows

- stream upon stream of water tumbled down.

- Such was my suitor.[31]

According to Homer, Niobe's tears – in her great mourning about her husband and children – contributed to the Achelous which she had found close to Mount Sipylus in what was to be Lydia.[32] Achelous was sometimes the father of the Sirens by Melpomene, or in a later version, they are from the blood he shed where Heracles broke off his horn.[33]

The mouth of the Achelous river was the spot where Alcmaeon finally found peace from the Erinyes.[34] Achelous offered him Callirhoe, his daughter, in marriage if Alcmaeon would retrieve the clothing and jewelry his mother Eriphyle had been wearing when she sent her husband Amphiaraus to his death. Alcmaeon had to retrieve the clothes from King Phegeus, who sent his sons to kill Alcmaeon.

Ovid in his Metamorphoses provided a descriptive interlude when Theseus is the guest of Achelous, waiting for the river's raging flood to subside: "He entered the dark building, made of spongy pumice, and rough tuff. The floor was moist with soft moss, and the ceiling banded with freshwater mussel and oyster shells."[35] In sixteenth-century Italy, an aspect of the revival of Antiquity was the desire to recreate Classical spaces as extensions of the revived villa. Ovid's description of the cave of Achelous provided some specific inspiration to patrons in France as well as Italy for the Mannerist garden grotto, with its cool dampness, tuff vaulting and shellwork walls. The banquet served by Ovid's Achelous offered a prototype for Italian midday feasts in the fountain-cooled shade of garden grottoes.

At the mouth of the Achelous River lie the Echinades Islands. According to Ovid's pretty myth-making in the same Metamorphoses episode, the Echinades Islands were once five nymphs. Unfortunately for them, they forgot to honor Achelous in their festivities, and the god was so angry about this slight that he turned them into the islands.

In Hellenistic and Roman contexts, the river god was often reduced to a mask and used decoratively as an emblem of water, "his uncut hair wreathed with reeds".[36] The feature survived in Romanesque carved details and flowered during the Middle Ages as one of the Classical prototypes of the Green Man.

Achelous and the River Achelous

Homer claims that the Achelous River was located in Lydia, near Mount Sipylos.[37] There were at least six different rivers with the name Achelous in ancient times,[38] all of which indicate that Achelous was originally not a single river, but a god of all water.

The origin of the river Achelous is described by Servius:

When Achelous on one occasion had lost his daughters, the Sirens, and in his grief invoked his mother Gaea, she received him to her bosom, and on the spot where she received him, she caused the river bearing his name to gush forth.[39]

Other accounts about the origin of the river and its name are given by Stephanus of Byzantium, Strabo,[40] and Plutarch.[41] Strabo proposes a very ingenious interpretation of the legends about Achelous, all of which according to him arose from the nature of the river itself. It resembled a bull's voice in the noise of the water; its windings and its reaches gave rise to the story about his forming himself into a serpent and about his horns; the formation of islands at the mouth of the river requires no explanation. His conquest by Heracles lastly refers to the embankments by which Heracles confined the river to its bed and thus gained large tracts of land for cultivation, which are expressed by the horn of plenty.[42][43]

Notes

- ↑ Isler, Hans Peter (1981). s.v. 'Acheloos'. Lexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae Vol. I. Zuerich: Artemis & Verlag. pp. 12–36.

- ↑ Molinari, Nicholas; Sisci, Nicola (2016). Potamikon: Sinews of Acheloios. A Comprehensive Catalog of the Bronze Coinage of the Man-Faced Bull, with Essays on Origin and Identity. Oxford: Archaeopress. pp. 60–2.

- ↑ G. B. D'Alessio (2004). "Textual Fluctuations and Cosmic Streams: Ocean and Acheloios". Journal of Hellenic Studies. London: The Council for the Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies. 124: 20–1.

- ↑ Isler, Hans Peter (1970). Acheloos: Eine Monographie. Bern: Verlag.

- ↑ Jannot, Jean-Rene. "Acheloos, le taureau androcephale et les masques cornus dans l'Etrurie archaique". Latomus. 33, 4.

- ↑ Molinari and Sisci (2016). Potamikon: Sinews of Acheloios. pp. 48–68.

- ↑ Molinari and Sisci (2016). Potamikon: Sinews of Acheloios. pp. 93–5.

- ↑ Homer, Iliad 21,194: "[…] it is not possible to fight Zeus, son of Kronos. Not powerful Akheloios matches his strength against Zeus […]".

- ↑ Pausanias, 8.38.10, remembering the line in Homer.

- ↑ Alcaeus, fragmentary quote.

- ↑ Hesiod, Theogony 337–345, 366–370.

- 1 2 3

- ↑ Herodotus, Histories ii. 10.

- ↑ Homer, Iliad xxi. 194

- ↑ Ephorus, quoted in Macrobius, v. 18.

- ↑ Ephorus, l.c..

- ↑ Virgil, Georgics i. 9.

- ↑ Molinari and Sisci (2016). Potamikon: Sinews of Acheloios. pp. 1–6.

- 1 2 Molinari and Sisci (2016). Potamikon: Sinews of Acheloios. pp. 22–30.

- 1 2 Molinari and Sisci (2016). Potamikon: Sinews of Acheloios. pp. 97ff.

- ↑ Molinari and Sisci (2016). Potamikon: Sinews of Acheloios. p. 14.

- ↑ Heffron, Yaǧmur; Brisch, Nicole (2016). "Asalluhi (god)". Ancient Mesopotamian Gods and Goddesses. University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- ↑ Whittaker, Gordon (2009). Milking the Udder of Heaven: A Note on Mesopotamian and Indo-Iranian Religious Imagery. From Daena to Din. Religion, Kultur und Sprache in der iranischen Welt: Festschrift fuer Philip Kreyenbroek zum 60. Geburstag. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 131.

- ↑ Pausanias iii. 18. § 9.

- ↑ Pausanias vi. 19. § 9.

- ↑ Comp. Philostr. Imag. n. 4.

- ↑ Molinari and Sisci (2016). Potamikon: Sinews of Acheloios. pp. 91–96.

- ↑ "Plaque with Hercules and Achelous". The Walters Art Museum.

- ↑ Apollodorus, 1.8.1, 2.7.5.

- ↑ Ovid, Metamorphoses ix, 1-88.

- ↑ Sophocles, The Trachiniae 9 ff., translated by Robert Torrance.

- ↑ Iliad xxiv. 602 ff.

- ↑ Kerényi 1951:56; Georg Kaibel, Comicorum Graecorum Fragmenta (Berlin) 1899, noted in Kerényi 1959:199.

- ↑ Apollodorus, 3.7.5.

- ↑ Ovid, Metamorphoses VIII, 547ff.

- ↑ Ovid, Metamorphoses ix.

- ↑ Homer. Iliad. p. 24.616.

- ↑ Molinari and Sisci (2016). Potamikon: Sinews of Acheloios. p. 61.

- ↑ Servius, ad Virg. Georg. i. 9; Aen. viii. 300.

- ↑ Strabo, x. p. 450.

- ↑ Plutarch, De Flum. 22.

- ↑ Strabo, x. p. 458.

- ↑ Compare Voss, Mythologische Briefe, lxxii.

References

- Andrews, Tamra. A Dictionary of Nature Myths, 1998. ISBN 0-19-513677-2.

- Apollodorus, The Library, with an English Translation by Sir James George Frazer. 2 voll. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, and London: William Heinemann Ltd., 1921 (online version at the Perseus Digital Library).

- Hesiod, Theogony, in The Homeric Hymns and Homerica with an English Translation by Hugh G. Evelyn-White, Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1914 (online version at the Perseus Digital Library).

- Isler, Hans Peter. Acheloos: Eine Monographie. Bern: Francke, 1970.

- Isler, Hans Peter. "Acheloos". LIMC, vol. 1, Zürich: Artemis & Verlag, 1981, p. 12–36.

- Jannot, Jean-Rene. "Acheloos, le taureau androcephale et les masques cornus dans l'Etrurie archaique," in Latomus 33, 4. Bruxelles: Latomus.

- Kerényi, Karl. The Heroes of the Greeks. New York and London: Thames and Hudson, 1959.

- Kerényi, Karl. The Gods of the Greeks. New York and London: Thames and Hudson, 1951.

- March, Jenny. Cassell’s Dictionary of Classical Mythology, 2001. ISBN 0-304-35788-X.

- Molinari, Nicholas, and Nicola Sisci. Potamikon: Sinews of Acheloios. A Comprehensive Catalog of the Bronze Coinage of the Man-Faced Bull, with Essays on Origin and Identity. Oxford: Archaeopress Archaeology, 2016. ISBN 9781784914011.

External links

- Theoi Project - Potamos Akheloios

- Nicholas J. Molinari and Nicola Sisci: