Icefall

An icefall is a portion of certain glaciers characterized by rapid flow and a chaotic crevassed surface. The term icefall is formed by analogy with the word waterfall, a similar, but much higher speed, phenomenon. When ice movement is faster than elsewhere, because the glacier bed steepens or narrows, the flow cannot be accommodated by plastic deformation and the ice fractures, forming crevasses. Where two fractures meet, seracs (ice towers) can be formed. When the movement of the ice slows down, the crevasses can coalesce, resulting in the surface of the glacier becoming smoother.[1]

Ice flow

Perhaps the most conspicuous consequence of glacier flow, icefalls occur where the glacier bed steepens and/or narrows. Most glacier ice flows at speeds of a few hundred metres per year or less. However, the flow of ice in an icefall may be measured in kilometres per year. Such rapid flow cannot be accommodated by plastic deformation of the ice. Instead, the ice fractures forming crevasses. Intersecting fractures form ice columns or seracs. These processes are imperceptible for the most part; however, a serac may collapse or topple abruptly and without warning. This behavior often poses the biggest risk to mountaineers climbing in an icefall.

Below the icefall, the glacier bed flattens and/or widens and the ice flow slows. Crevasses close and the glacier surface becomes much smoother and easier to traverse.

Examples

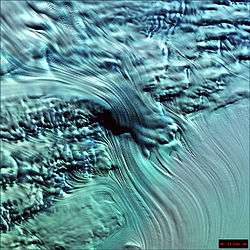

Icefalls vary greatly in height. The Roosevelt Glacier icefall, on the north face of Mount Baker (Cascade Range, U.S.), is about 730 metres (2,400 ft) high (photograph at right). The ice cliff of the left side of the ice fall and above the debris covering the glacier is 20 to 40 metres (70 to 140 ft) high. Typical of mountain glaciers, this icefall forms as the ice flows from a high elevation plateau or basin accumulation zone to a lower valley ablation zone. Much larger icefalls may be found in the outlet glaciers of continental ice sheets. The icefall feeding the Lambert Glacier in Antarctica (photograph at left) is 7 kilometres (4.4 mi) wide and 14 kilometres (9 mi) long, even though the elevation difference is only 400 metres (1,300 ft), a little more than half that of the Roosevelt Glacier icefall.

Icefalls are climbed because of their beauty and the challenge they pose. In some cases, an icefall may provide the only feasible or the easiest route up one face of a mountain. An example is the Khumbu Icefall on the Nepalese side of Mount Everest, variously described as "treacherous" and "dangerous." It is about 5,500 metres (18,000 ft) above sea level.

An icefall feeding into the Lambert Glacier, Antarctica. |

The Khumbu Icefall on Mount Everest |

A small icefall on east lobe of the new Crater Glacier on Mount Saint Helens. |

1849 Balvullich ice fall

In 2016 the Guinness Book of World Records called a solid mass of ice weighing "nearly a ton" was found to have "landed" at a farm near the Scottish town of Balvullich on July 30, 1849 the "Largest Piece of Fallen Ice". In 1980 Arthur C. Clark speculated that it might have been a piece of a comet. The farmer reported hearing "one of the loudest peals of thunder we ever heard" and found a "irregular shaped mass of ice... twenty feet in circumference. It had a salty taste and nearly was transparent. Environmental physicist, Randall Osczevski who is an authority on wind chill, believes he solved the mystery of the ice mass. Using weather reports from newspapers and Google Maps, he discovers that 1849 was at the very end of the "Little Ice Age" and in February it looked like spring had arrived, but March - June were very cold, some of the coldest in "living memories" according to local contemporary newspapers. Osczevski believes that the salty taste, rounded shape and translucent appearance of the ice means that it was actually a frozen pond that became dislodged by a warm thunderstorm in July. The rain "dislodged a large piece of the pond's thick covering of ice, and washed it down the slope" which was a 12 percent grade. The ice slid towards the farm, rotating and rounding its edges as it went, causing a very loud sound and a sensation for the media. Osczevski believes that it is possible to model and test his hypothesis.[2]

See also

References

External links