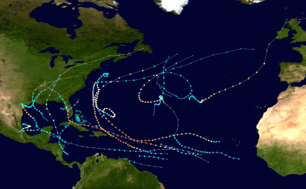

Hurricane Ophelia (2017)

| Category 3 major hurricane (SSHWS/NWS) | |

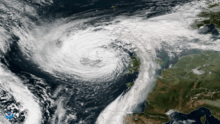

Hurricane Ophelia at peak intensity south of the Azores on 14 October | |

| Formed | 9 October 2017 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | 18 October 2017 |

| (Extratropical after 16 October) | |

| Highest winds |

1-minute sustained: 115 mph (185 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 959 mbar (hPa); 28.32 inHg |

| Fatalities | 2 direct, 3 indirect |

| Damage | > $13.6 million (2017 USD) |

| Areas affected | Azores, Portugal, Spain, France, Ireland, United Kingdom, Norway, Sweden, Finland, Estonia, and Russia |

| Part of the 2017 Atlantic hurricane and 2017–18 European windstorm seasons | |

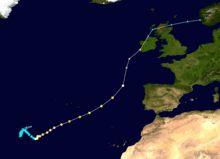

Hurricane Ophelia (known as Storm Ophelia in Ireland and the United Kingdom while extratropical) was regarded as the worst storm to affect Ireland in 50 years, and was also the easternmost Atlantic major hurricane[nb 1] on record. The tenth and final consecutive hurricane and the sixth major hurricane of the very active 2017 Atlantic hurricane season, Ophelia had non-tropical origins from a decaying cold front on 6 October. Located within a favorable environment, the storm steadily strengthened over the next two days, drifting north and then southeastwards before becoming a hurricane on 11 October. After becoming a Category 2 hurricane and fluctuating in intensity for a day, Ophelia intensified into a major hurricane on 14 October south of the Azores, brushing the archipelago with high winds and heavy rainfall. Shortly after achieving peak intensity, Ophelia began weakening as it accelerated over progressively colder waters to its northeast towards Ireland and Great Britain. Completing an extratropical transition early on 16 October, Ophelia became the second storm of the 2017–18 European windstorm season. Early on 17 October, the cyclone crossed the North Sea and struck western Norway, with wind gusts up to 70 kilometres per hour (43 mph) in Rogaland county, before weakening during the evening of 17 October. The system then moved across Scandinavia before dissipating over Russia.

Three deaths can be directly attributed to Ophelia, all of which occurred in Ireland. Total losses from the storm were far less than initially feared, with a minimum estimate of total insured losses across Ireland and the United Kingdom of US$13.6 million.[2]

Meteorological history

On 6 October, the United States' National Hurricane Center (NHC) began monitoring the tail end of a decaying cold front for possible subtropical or tropical cyclogenesis.[3] On the same day, a circulation developed on the periphery of this front.[3] Soon afterwards, a non-tropical low developed within the circulation, and drifted to the southwest before becoming nearly stationary.[4] The system began to acquire subtropical characteristics on the next day, and the chances of development were raised to a high percentage of cyclogenesis.[5] After a brief loss of organization and diminished convection, due to moderate wind shear,[6] the system continued to steadily organize, and developed a well-defined circulation center early on 9 October, as deep convection began to persist near the center.[7] By 09:00 UTC that day, the convection had persisted long enough for the system to be classified as a tropical depression about 875 mi (1,410 km) west-southwest of the Azores, and the storm was identified as Tropical Depression Seventeen.[8][9] A curved banding feature wrapped around the center as the satellite presentation improved, leading to the upgrade to Tropical Storm Ophelia six hours later.[10]

Despite marginally warm sea surface temperatures of around 79 °F (26 °C), the effects of below-average air temperatures aloft and low wind shear allowed Ophelia to gradually strengthen; with banding features becoming more prominent as it drifted northward, in an area of weak steering currents.[11] In addition, the large temperature contrast between the unusually-warm ocean surface (for that time of the year) and the extremely cold temperatures in the upper atmosphere provided instability for Ophelia's thunderstorms, which allowed the storm to continue strengthening, despite being over marginally-warm ocean temperatures.[12] A slight degradation of the structure of the storm resulted in some weakening early on 11 October,[13] but this was short-lived as deep convection wrapped around the entire storm. It was upgraded to a hurricane at 21:00 UTC that day after a ragged eye developed, becoming the record-tying tenth consecutive hurricane to form during the 2017 hurricane season; Ophelia was the fourth such occurrence since the 1878, 1886, and 1893 seasons.[14][15][nb 2] Afterwards, Ophelia steadily intensified as it became nearly stationary, intensifying into a Category 2 hurricane on the Saffir–Simpson scale on 12 October, as the central dense overcast became more symmetric and the eye became better defined.[16]

The hurricane then weakened slightly on the following day, as cloud tops warmed,[17] only to quickly strengthen as the eye became much more defined and cloud tops cooled significantly due to outflow from a strong trough to the northeast. The NHC upgraded the storm to a major hurricane (Category 3 or higher) at 15:00 UTC on 14 October; at 26.6°W, this was the farthest east that a storm of such intensity had been observed in the satellite era.[18][19] At the same time, it attained its peak intensity with winds of 115 mph (185 km/h) and a minimum pressure of 959 millibars (28.32 inHg) while located approximately 235 miles (375 km) southeast of the Azores. After peaking in intensity, increasing shear and dry air from an encroaching frontal boundary began to disrupt the core of the storm, which caused Ophelia to begin weakening early on 15 October, as it began its extratropical transition, with the eye collapsing.[20] The process accelerated as Ophelia became further embedded in the trough, and ultimately, the storm became extratropical at 03:00 UTC on the next day.[21] Ophelia then made landfall in Ireland as a hurricane-force European windstorm. Afterward, Ophelia weakened, tracked over the UK, and turned eastward. Late on 17 October, Ophelia's remnant made landfall over Norway, before dissipating shortly afterward, on 18 October.[2]

Preparations and impact

Azores

The Portuguese Institute of the Sea and the Atmosphere issued a red warning for heavy rainfall for the eastern group of the Azores—São Miguel, Santa Maria and Formigas—on 14 October from 17:59 UTC to 23:59 UTC.[22] An orange gale warning was issued for the eastern group for the afternoon through night of 14–15 October,[22] as well as a yellow alert for high seas.[22] Rainfall alerts were also issued for the central group—Terceira, Graciosa, São Jorge Island, Pico and Faial.

The President of the Regional Service of Civil Protection of the Azores, Lieutnant-Colonel Carlos Neves, announced there was no serious damage. High winds downed four trees on São Miguel, three in the Ponta Delgada district and one in Povoação. The island also experienced some minor flooding. In the central group of the Azores, there were a few instances of light damage, with one home suffering a roof leak.[23]

Iberia

Starting on 15 October 2017, winds from Ophelia fanned wildfires in both Portugal and Spain. The wildfires have claimed the lives of at least 49 individuals, including 45 in Portugal and four in Spain, and dozens more were injured.[24][25][26][27][28] In Portugal, more than 4,000 firefighters battled around 150 fires.[29] The National Hurricane Center's Tropical Cyclone Report on Hurricane Ophelia makes no mention of the fires, thus the associated fatalities are not included as part of the storm total.[2]

Republic of Ireland

Met Éireann, Ireland's national meteorological service, reported on 12 October that the storm would reach Ireland. On 14 October, it issued a 'Status Red' warning, its highest storm category,[30] for portions of Ireland.[31][32] Issuing such a warning more than 48 hours in advance was "unprecedented," as such warnings are normally issued within 24 hours of the event.[33] On 15 October, the National Emergency Coordination Centre and Met Éireann convened to advise the public in relation to the post-tropical storm reaching the Republic of Ireland. At 20:15 on the 15th, 'status red' was extended to all of Ireland,[33] and all public education services were confirmed as cancelled.[34]

The Department of Education and Skills confirmed that all Montessoris, creches, primary and post-primary schools would be closed on 16 and 17 October.[35][36] Other public services would be withdrawn such as Court and District Court services, third-level institutes such as UCC, CIT, University of Limerick, and Waterford Institute of Technology.[37] Aer Lingus confirmed a number of flights from Cork Airport and Shannon Airport would be cancelled, with the likelihood of 50 flights being cancelled.[38] All public transport previously scheduled within the red alert zone were cancelled including bus, rail and ferry journeys. Bus Éireann announced the cancellation of school bus services for the west of Ireland after Met Éireann issued a rare Status Red warning affecting the south western and western counties of Wexford, Waterford, Cork, Kerry, Clare, Mayo and Galway.[39] The Department of Housing, Planning and Local Government confirmed members of the public should not make any unnecessary journeys especially travelling within the red level warning areas and the department reiterated the storm's potential risk to life.[40]

On 16 October, gusts of up to 191 km/h (119 mph) were recorded at Fastnet Rock off the coast of County Cork, the highest wind speeds ever recorded in Ireland. 10-minute sustained wind speeds at Roches Point, Co. Cork, reached 111 km/h (69 mph), with gusts of 156 km/h (97 mph).[41]

ESB Group confirmed that more than 360,000 customers were without power in the wake of the storm.[42][43] Two people, a man in Dundalk and a woman in Aglish, County Waterford, were killed when trees fell on their cars.[44][45] In County Tipperary, another fatality occurred when a man was clearing a fallen tree with a chainsaw.[46] Two men died in separate incidents after suffering fatal injuries while carrying out repairs to damage caused by Ophelia and Storm Brian. In Cork, a man died after he fell while working on a shed roof, and in County Wicklow another man died after falling from a ladder while carrying out repairs to his farm shed.[47] On 16 October, it was estimated that Ophelia had caused €1.5 billion (US$1.77 billion) worth of losses in Ireland, mostly due to the shutdown of economic activities on the day of its passage.[48] As of 24 October, insurance claims across Ireland reached €6 million (US$7 million), primarily coming from residents in Cork and Tipperary.[49] Insured damage is not expected to exceed that of Storm Darwin in 2014, which resulted in €111 million (US$131 million) in payouts.[50]

United Kingdom

The Met Office in the United Kingdom issued the first severe weather warnings for Ophelia on 12 October, referring to the hurricane as "ex-Ophelia" in the context of the 2017–18 UK and Ireland windstorm season.[22] The severe weather warning initially issued on 12 October was a yellow weather warning for wind, covering Northern Ireland, northern England, Wales, south west England and southern and western Scotland, valid between 12:00 and 23:55 BST on 15 October.[22] The weather warning impact matrix warned of relatively severe impacts anticipated, although with a low level of certainty so far in advance preventing the issuance of amber weather warnings initially.[22] Subsequently, on 13 October, a yellow severe weather warning for wind was issued for Northern Ireland, southern Scotland and northern England, valid between 00:05 and 15:00 BST on 17 October. On 15 October, the weather warning for wind in Northern Ireland on 16 October was upgraded to an amber weather warning.

The arrival of Ophelia brought Saharan dust to parts of the United Kingdom, giving the sky an orange or yellow-sepia appearance, and the sun a red or orange appearance.[51][52] A strange 'burning' smell was also reported across Devon, also attributed to the dust, and smoke from forest fires in Portugal and Spain.[53] Winds up to 115 km/h (71 mph) were observed in Orlock Head, County Down, at the height of the storm. Approximately 50,000 households lost power in Northern Ireland. Insurance claims from Northern Ireland, Wales, and Scotland are estimated to reach £5–10 million (US$6.6–13.2 million).[54]

Estonia

In Tallinn, Estonia, black rain fell because Ophelia brought smoke and the soot of fires to Estonia from Portugal, as well as dust from the Sahara Desert, Report informs citing the Estonian media. "We looked at photos from satellites and the Finnish weather service confirmed that the smoke and soot of the fires in Portugal and partly the dust from the Sahara reached us," meteorologist Taimi Paljak said.[55][56]

Relation to climate change

Climate scientist Reindert Haarsma of the Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute said that climate change is likely to cause Europe to see more hurricanes like Ophelia, as the oceans get warmer, although they were still comparing their model's results (previously reported in 2013) with those from other climate centres.[57] But UCD Professor Ray Bates and Ray McGrath (also of UCD) argued that "insofar as the influence of the sea surface temperature is concerned, the exceptional strength of Storm Ophelia was due to natural variability" rather than global warming.[58]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hurricane Ophelia (2017). |

- Tropical cyclone effects in Europe – Other former tropical storms that have affected Europe in the past

- Hurricane Vince of 2005 – easternmost Atlantic hurricane on record that made an extremely rare landfall on the Iberian Peninsula, as a tropical depression

- Hurricane Debbie of 1961 – caused severe impacts in Europe as a powerful extratropical cyclone

- Tropical Storm Grace of 2009 – is considered the north-easternmost tropical cyclone to form in the North Atlantic basin.

- Great Storm of 1987 – a deadly and destructive extratropical cyclone that impacted the United Kingdom exactly 30 years beforehand.

- Hurricane Lili of 1996 – hurricane which struck the United Kingdom and Ireland as an extratropical storm, causing over £150,000,000 of damage and resulted in the loss of six lives in the UK.

- Cyclone Tini – Also known as Storm Darwin, a previous strong windstorm which affected Ireland in 2014.

- October 2017 Iberian wildfires – A series of catastrophic wildfires fanned by Hurricane Ophelia

- Hurricane Leslie (2018) – A long-lived hurricane that also impacted the Iberian Peninsula

Notes

- ↑ A major hurricane is a storm that ranks as Category 3 or higher on the Saffir-Simpson hurricane wind scale.[1]

- ↑ It should be noted that 1878, 1886, and 1893 also had ten consecutive hurricanes form; however as these years are several decades before the advent of satellite data (post-1966), these years may be considered unreliable as several tropical storms in between could have been easily missed.

References

- ↑ Christopher W. Landsea; Neal M. Dorst (ed.) (June 2, 2011). "A: Basic Definitions". Hurricane Research Division: Frequently Asked Questions. Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. A3) What is a super-typhoon? What is a major hurricane ? What is an intense hurricane ?. Archived from the original on June 15, 2006. Retrieved May 4, 2013.

- 1 2 3 Stacy R. Stewart (March 27, 2018). Tropical Cyclone Report: Hurricane Ophelia (PDF) (Report). Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved April 14, 2018.

- 1 2 "Two-Day Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. 6 October 2017. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- ↑ "Two-Day Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. 6 October 2017. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- ↑ "Two-Day Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. 7 October 2017. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- ↑ "Two-Day Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. 8 October 2017. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- ↑ "Two-Day Graphical Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. 8 October 2017. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- ↑ Cangialosi, John (9 October 2017). "Tropical Depression Seventeen Advisory Number 1". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- ↑ Cangialosi, John (9 October 2017). "Tropical Depression Seventeen Discussion Number 1". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- ↑ Stewart, Stacy (9 October 2017). "Tropical Storm Ophelia Discussion Number 2". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- ↑ Cangialosi, John (9 October 2017). "Tropical Storm Ophelia Discussion Number 5". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- ↑ Dennis Mersereau (12 October 2017). "Hurricane Ophelia is one extremely weird storm". Popular Science. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- ↑ Brown, Daniel (11 October 2017). "Tropical Storm Ophelia Discussion Number 8". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- ↑ Zelinsky, David (11 October 2017). "Hurricane Ophelia Discussion Number 11". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- ↑ Astor, Maggie (11 October 2017). "10 Weeks, 10 Hurricanes, and a 124-Year-Old Record Is Matched". The New York Times.

- ↑ Zelinsky, David (12 October 2017). "Hurricane Ophelia Discussion Number 15". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 14 October 2017.

- ↑ Brennan, Michael (13 October 2017). "Hurricane Ophelia Discussion Number 18". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 14 October 2017.

- ↑ Avila, Lixion (14 October 2017). "Hurricane Ophelia Discussion Number 22". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 14 October 2017.

- ↑ Philip Klotzbach [@philklotzbach] (14 October 2017). "Ophelia is now a major hurricane - the farthest east (26.6°W) an Atlantic major hurricane has existed on record" (Tweet). Retrieved 14 October 2017 – via Twitter.

- ↑ Avila, Lixion (15 October 2017). "Hurricane Ophelia Discussion Number 26". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 17 October 2017.

- ↑ Berg, Robbie (16 October 2017). "Post-Tropical Cyclone Ophelia Discussion Number 28". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 17 October 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Critérios de Emissão dos Avisos Meteorológicos" [Weather Warnings Emission Criteria] (in Portuguese). IPMA).

- ↑ "Passagem de furacão sem ocorrências graves" (in Portuguese). Açoriano Oriental.

- ↑ "UPDATE: Portugal forest fires death toll rises to 45". ENCA World. 2017-10-24. Retrieved 2017-10-25.

- ↑ Limited, Bangkok Post Public Company. "39 dead in 'terror-arson' fires in Portugal, Spain". Bangkok Post. Retrieved 16 October 2017.

- ↑ Badcock, James. "At least 27 dead as Ophelia winds fan wildfires in Portugal". Telegraph. Retrieved 16 October 2017.

- ↑ "At least 30 killed as Ophelia winds fan wildfires in Portugal and Spain". The Guardian. The Guardian. Retrieved 16 October 2017.

- ↑ Minder, Raphael. "Deadly Fires Sweep Portugal and Northern Spain". New York Times. New York Times. Retrieved 16 October 2017.

- ↑ Vonberg, Judith. "Portugal and Spain wildfires kill at least 35 people". cnn.com. Retrieved 16 October 2017.

- ↑ "Met Éireann Weather Warning System Explained". Met Éireann.

- ↑ Salmon, Natasha (14 October 2017). "Hurricane Ophelia: Ireland issues highest possible 'status red' weather warning". The Independent.

- ↑ "Hurricane Ophelia warning at highest level Status Red - Northern Ireland braced for impact". Belfast Telegraph. 14 October 2017.

- 1 2 Byrne, Luke; McDonnell, Mary (15 October 2017). "'This is not the remnants of a hurricane, this IS a hurricane' - Red weather warning extended nationwide as Hurricane Ophelia barrels in". Irish Independent.

- ↑ "All schools and colleges and creches to remain closed today, Department of Education confirms". Irish Independent. 15 October 2017.

- ↑ "All schools and colleges and creches to remain closed Monday, Department of Education confirms - Independent.ie". Independent.ie. Retrieved 16 October 2017.

- ↑ Bruton, Richard (16 October 2017). "Following careful consideration by the National Emergency Coordination Group, the Department of Education and Skills, has decided that all schools will remain closed tomorrow #Ophelia". @RichardbrutonTD. Retrieved 16 October 2017.

- ↑ "Schools shut, court sittings cancelled over Ophelia". RTÉ.ie. 15 October 2017.

- ↑ "A number of flights on Mon 16 Oct are cancelled due to severe weather". Aer Lingus.

- ↑ "Bus Éireann cancels school buses over Hurricane Ophelia". RTE.ie. 14 October 2017. Retrieved 14 October 2017.

- ↑ Kiernan, Eddie (15 October 2017). "Statement from the National Emergency Coordination Group on Severe Weather" (Press release). Department of Housing, Planning and Local Government.

- ↑ Siggins, Lorna (18 October 2017). "Storm Ophelia: Facts and figures of the strongest east Atlantic hurricane in 150 years". Irish Times. Retrieved 20 October 2017.

- ↑ "Storm Ophelia: 360,000 customers without electricity". thejournal.ie.

- ↑ Samenow, Jason. "Former Hurricane Ophelia rocks Ireland with 100-mph wind gusts". washingtonpost.com. The Washington Post. Retrieved 16 October 2017.

- ↑ Feeney, Oisin. "BREAKING: Man passes away after car hit by tree in Dundalk | Buzz.ie". Buzz.ie. Retrieved 16 October 2017.

- ↑ "Irish Times Live Blog". Irish Times. 16 October 2017.

- ↑ News, Today FM (16 October 2017). "Second fatality from Ophelia". @TodayFMNews. Retrieved 16 October 2017.

- ↑ "Storm Ophelia aftermath: Two men killed while repairing damage at home named locally - Independent.ie". Independent.ie. Retrieved 2017-10-25.

- ↑ Robin Schiller (16 October 2017). "Hurricane Ophelia could cause €1.5bn in damage - expert analyst". Irish Independent. Retrieved 17 October 2017.

- ↑ Fiona Reddan (24 October 2017). "Storm Ophelia to cost FBD from €4m to €6m". Irish Times. Retrieved 27 October 2017.

- ↑ Joe Brennan (20 October 2017). "Storm Ophelia insurance costs unlikely to exceed €111m". Irish Times. Retrieved 20 October 2017.

- ↑ "Red sun phenomenon 'caused by Hurricane Ophelia'". BBC News. 16 October 2017.

- ↑ "Ex-hurricane Ophelia and the red sun". Royal Meteorological Society. 17 October 2017.

- ↑ "This is why the sky is strange and you can smell burning in Devon and Cornwall". Plymouth Herald. 16 October 2017.

- ↑ Rachel Martin (20 October 2017). "Ophelia: NI and GB damage estimated to cost up to £10m". AgriLand. Retrieved 20 October 2017.

- ↑ Black rain observed in Tallinn due to hurricane Ophelia, Report News Agency, 26.10.2017

- ↑ Galerii: torm Ophelia kandis koos Sahara tolmuga Eestisse pimeduse, postimees.ee, 26.10.2017, in Estonian

- ↑ Reindert Haarsma (16 October 2017). "The future will bring more hurricanes to Europe". RTE. Retrieved 20 October 2017.

We're likely to see more hurricanes like Ophelia in the coming years as the earth's climate warms. ... These results are based on the simulations of a single model, and to test their robustness we are now comparing our results with those of other similar simulations done in other climate centres. However, the implications remain clear: Europe will see more hurricanes as a result of climate change.

Original article's title and date: The future will bring hurricanes to Europe, July 28, 2013

by ... Reindert Haarsma, Senior Scientist, Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article. - ↑ Ray Bates; Ray McGrath (25 October 2017). "What Caused Storm Ophelia?". Royal Irish Academy. Retrieved 9 November 2017.

The increase in the global-mean values in the period from the 1940s to the present, which is the period when the effect of greenhouse gases due to human activities has been most significant, amounts to about 0.4°C. This is only a tenth of the naturally occurring variation in sea surface temperature seen in the Azores-to-Ireland region in the 3 months prior to Storm Ophelia. This indicates that, insofar as the influence of the sea surface temperature is concerned, the exceptional strength of Storm Ophelia was due to natural variability.

External links

- The National Hurricane Center (NHC)'s advisory archive on Hurricane Ophelia

- German met office Weather map showing Ophelia isobars over Ireland

- European Emergency Response Coordination Centre (ERCC) Echo daily map for Ophelia