Hmong textile art

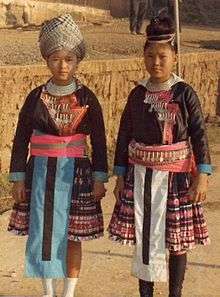

Hmong textile art (RPA:Paj ntau or Paj ntaub, or "flower cloth" in the Hmong language; sometimes transliterated as pa ntau) consists of textile arts traditionally practiced by Hmong people. Closely related to practices of other ethnic minorities in China, the embroidery consists of bold geometric designs often realized in bright, contrasting colors. Different patterns and techniques of production are associated with geographical regions and cultural subdivisions within the global Hmong community.[1] For example, White Hmong are typically associated with reverse appliqué while Green Mong are more associated with batik. Since the mass exodus of Hmong refugees from Laos following the end of the Secret War, major stylistic changes occurred, strongly influenced by the tastes of the Western marketplace. Changes included colors that are more subdued and the invention of a new form of paj ndau often referred to as "story cloths." Because Hmong language did not become alphabetized until 1950, many Hmong refugees did not record their histories in writing.[2] These “story cloths” became a recording and expression of both individual and collective experiences including trauma and loss across generations.[2]

These cloths, ranging in size up to several square feet, use figures to represent stories from Hmong history and folklore in a narrative form. Today, the practice of embroidery continues to be passed down through generations of Hmong people and paj ndau remain important markers of Hmong ethnicity. While traditional designs are not an alphabet in any strict linguistic definition, the patterns were a shared visual language or alternative text that fellow Hmong understood and that were important in the ritual functions of paj ndaub.[3]

Traditionally, paj ndau were applied to skirts worn for courtship during New Year festivals, as well as baby-carriers, and men's collars. The core visual elements of "layered bands of appliqué, triangles, squares tilted and superimposed on contrasting, squares, lines and dots, spirals, and crosses." The use of border patterns may show the influence of Chinese embroidery techniques.

Role of Gender in Hmong Textile Art

In traditional Hmong villages in Asia, women exerted cultural agency through their production of elaborate clothing.[3] The profound relevance of textiles as infrastructure in the Hmong social fabric is not strictly historical, as diasporic and Hmong women in Asia claim space for textile production. A young woman’s industriousness and textile skills were among the most highly regarded attributes of a partner when a young man was searching for his future wife.[4] The cultural dynamic “story cloths” inhabit is more than what first meets the eye. The cloths are included in many different aspects of Hmong culture and life. “Story cloths” could potentially even determine a woman’s fertility. A woman’s inventiveness in textile pattern design was also reported to be an indicator of her future fertility in childbirth.

The development of commercialized textiles produced confusion over how gender was connected with needlework, as the arena of trade had been clearly male in Laos.[4] Needlework helped challenge the structure of some of the gender roles that the Hmong people held.[4] This type of needlework required much work and cooperation from both males and females. Many men in the camps had learned the skills necessary to produce paj ntaub, but sewing remained a primarily a woman’s tradition.[5] “Men, however, draw the penciled outlines for most story cloths”.[5]

Refugee experience

When communist forces took control of Laos in 1975, Hmong people who supported the Royal Lao Government and fought for the American CIA during the Secret War were singled out for retribution. Tens of thousands of Hmong people escaped into Thailand as part of a mass exodus of 300,000 refugees.[6] Once in Thailand, most spent several years in overcrowded refugee camps awaiting resettlement. Refugee camps provide limited gratuitous services. Most refugees must supplement subsistence-level support programs and allotments by relying on sparse savings and assistance from relatives, or by earning what they can through craft production.[5] Dependence on relief agencies for subsistence rose; many Hmong people began selling handicrafts to improve their standard of living. Story cloths are stylized in their narratological sequence of the fighting with Pathet Lao or Vietcong, the escape through jungles, the crossing of the Mekong River, and the arrival at Thai refugee camps, unfolding in several horizontal planes while refugees’ zigzag route brings attention downward. The narratives of the Hmong people unfolded as they were sewn in. From an outsider’s perspective, there is room to interpret the stories, but these generalizations should be interpreted with caution. The comprehensive reading of a story cloth invites us to decode messages that extend beyond the realities of economic incentive, material form, and skilled technique, thought these are integral to any interpretation.[5] From the viewpoint of the Hmong people, specifically Hmong women, the narratives are clear and necessary. The crucial criterion informing their aesthetic appraisal is moral in the sense that story cloths are admired for how well they represent the truth and past.[5]

Research indicates that the sale of acculturated pay ntaub squares to tourists began in Laos as early as the 1950s, but that production and commerce were limited to less isolated villages.[3] As early as 1976, NGOs, like the Christian and Missionary Alliance, coordinated with Hmong women to sell their needlework abroad. In Laos, only rare moments of free time were spent on embroidery to adorn pieces of clothing for important rituals. Now with time to spare in the camps, women produced purses, bed spreads, and toaster covers which were shipped to relatives abroad who could sell them and send money back.

Men also contributed to the endeavor by creating drawings that could be transferred to cloths. In the 1960s, missionaries had taught men to draw illustrations for the folktales used in literacy primers. Cloths featuring elaborate and fantastic narratives sold well overseas and production grew. These cloths were not always items to be celebrated and commoditized. Engrained in the fabric of many of these items were horrid memories contained by narratological stylizations, but such containment, as illustrated in nearly all story cloths, never fails to cease at the exact moment of departure for the West.

Textile Art in the United States

Assimilation and acculturation is expected when any population migrates to another country. This is not an exception for the Hmong people. The textile art the Hmong people produced was influenced by Western standards when they were still in the Thai refugee camps. Living in the United States changed the way that the Hmong people produced their textile art. Traditional standards blurred and deviation from the norm increased. Paj ntaub clothing as cultural agent and artifact now has different symbolic relevance in both Asia and the diaspora (to Hmong and non-Hmong) but is still useful for maintaining group identity. The central factors behind the “cloth story” have remained.[3]

There are many ways that we can reimagine the practices that tie into the field. There can always be change occurring throughout the world. Like many indigenous cultures, Hmong culture—as understood in the scholarly field—is bound up in Western notions and ideologies due to colonial and hegemonic writings of history.[2] The struggle for authenticity remains.

Camacrafts is a non-profit who began working with Hmong in the refugee camps in Thailand in the late 1970’s to maintain traditional craft skills through production of textiles for sale to tourists in Asia or to be sent abroad to relatives in the U.S.[4] Camacrafts created a catalog of designs and colors suited to Western non-Hmong tastes, which allowed the products to be ordered and purchased from buyers abroad.[4] These works initially translated over to the United States. The elaborate paj ntaub garments were the most identifiable markers of “otherness,” which mainstream Americans and politicians primarily saw at Hmong New Year festivals.[3] The “otherness” is a factor that has consequences for the larger communities as a whole in the proceeding generations. With the change that is to come, one must recognize that Hmong story cloths on the refugee saga allegedly arose in Thai refugee camps and are now a staple in arts and crafts festivals in the U.S. The integration of Hmong textile art in the United States by Hmong-Americans has and will continue to be influenced by social, cultural, financial, political and religious factors. The evolutionary path that the story cloth takes will be one of interesting note.

Textile Art and Religion

Animism, one of the oldest belief systems in the world, is central to the Hmong people. The textile art that produced has religious and spiritual connections. Paj ntaub have a variety of purposes. The paj ntaub—ascribed meaning by design and ritual use within an animist cosmology—can be seen as an alternative text and a visual manifestation of cultural maintenance in an ethnic group in which orality was a primary cultural script.[3] Some textiles with specific “way- finding” patterns stitched by family members were elements in burial rituals to help “show the way” back to one’s ancestors in the afterlife.[3] This is not uncommon; Hmong clothing in Asia was part of a rich cosmological and psychosensory world for centuries, where material constructs (textiles, architecture, jewelry) served their users in cultural, historical, and political ways.[3] In fact, the Hmong New Year was when new garments were revealed and displayed on all members of the family, but most significant for young women of marriageable age.[4]

Religion-centered paj ntaub grew in popularity throughout America, specifically in Christian Hmong communities. Christian Hmong in the United States sew cross-stitched story cloths that echo religious themes.[5] Conversion by religious based NGO’s might be a factor.

Textile Art Economics

Textile arts, which combine the human desire to create beauty with the human need to sell products in order to gain a livelihood, can also illustrate the changing economic structure of people within a culture.[7] Although sold to an external audience, they are produced according to an internal standard.[5] Older Hmong women in the United States still create elaborate Hmong clothing for nieces, daughters and granddaughters.[8] And though such clothing is an important source of cultural identity for the Hmong, it's questionable whether such traditional attire will continue to survive beyond the next generation. Many young women now pursuing an education don't have the time to commit to years of practice in becoming proficient in Hmong paj ntaub techniques. The story cloth phenomenon is art, craft, and industry; export, history, value, and experience; they shape the reflections of those who view them.[5]

References

- ↑ Hmong - The Virtual Hilltribe Museum @ www.hilltribe.org

- 1 2 3 "https://carleton-primo.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com/primo-explore/fulldisplay?docid=TN_gale_ofa472266220&context=PC&vid=01BRC_CCO&search_scope=Everything&tab=default_tab&lang=en_US". carleton-primo.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com. Retrieved 2017-02-21. External link in

|title=(help) - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "https://carleton-primo.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com/primo-explore/fulldisplay?docid=TN_jstor_books_chapj.ctt1b4cx58.11&context=PC&vid=01BRC_CCO&search_scope=Everything&tab=default_tab&lang=en_US". carleton-primo.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com. Retrieved 2017-02-21. External link in

|title=(help) - 1 2 3 4 5 6 "https://carleton-primo.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com/primo-explore/fulldisplay?docid=TN_gale_ofa247740086&context=PC&vid=01BRC_CCO&search_scope=Everything&tab=default_tab&lang=en_US". carleton-primo.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com. Retrieved 2017-02-22. External link in

|title=(help) - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "https://carleton-primo.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com/primo-explore/fulldisplay?docid=TN_gale_ofa6512901&context=PC&vid=01BRC_CCO&search_scope=Everything&tab=default_tab&lang=en_US". carleton-primo.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com. Retrieved 2017-02-22. External link in

|title=(help) - ↑ Lee, Gary Yia (1990). "Refugees from Laos: Historical Background and Causes". Retrieved 2007-05-09.

- ↑ "https://carleton-primo.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com/primo-explore/fulldisplay?docid=TN_proquest210633217&context=PC&vid=01BRC_CCO&search_scope=Everything&tab=default_tab&lang=en_US". carleton-primo.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com. Retrieved 2017-02-22. External link in

|title=(help) - ↑ "https://carleton-primo.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com/primo-explore/fulldisplay?docid=TN_proquest195810596&context=PC&vid=01BRC_CCO&search_scope=Everything&tab=default_tab&lang=en_US". carleton-primo.hosted.exlibrisgroup.com. Retrieved 2017-02-22. External link in

|title=(help)

External links

- Threads of life a video about paj ndau produced by Stone Soup Fresno

- Images of paj ndau from the collections of the University of California - Irvine

- Bibliography from the Hmong Culture and Resource Center