Textile industry

The textile industry is primarily concerned with the design, production and distribution of yarn, cloth and clothing. The raw material may be natural, or synthetic using products of the chemical industry.

Industry process

Cotton manufacturing

| Bale Breaker | Blowing Room | |||||

| Willowing | ||||||

| Breaker Scutcher | Batting | |||||

| Finishing Scutcher | Lapping | |||||

| Carding | Carding Room | |||||

| Sliver Lap | ||||||

| Combing | ||||||

| Drawing | ||||||

| Slubbing | ||||||

| Intermediate | ||||||

| Roving | Fine Roving | |||||

| Mule Spinning | - | Ring Spinning | Spinning | |||

| Reeling | Doubling | |||||

| Winding | Bundling | Bleaching | ||||

| Weaving shed | Winding | |||||

| Beaming | Cabling | |||||

| Warping | Gassing | |||||

| Sizing/Slashing/Dressing | Spooling | |||||

| Weaving | ||||||

| Cloth | Yarn (Cheese)- - Bundle | Sewing Thread |

Cotton is the world's most important natural fibre. In the year 2007, the global yield was 25 million tons from 35 million hectares cultivated in more than 50 countries.[1] There are five stages:[2]

- Cultivating and Harvesting

- Preparatory Processes

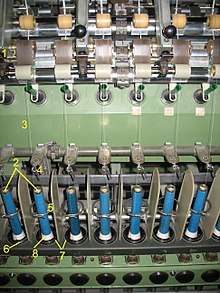

- Spinning — giving yarn

- Weaving — giving fabrics [lower-alpha 1]

- Finishing — giving textiles

Synthetic fibres

Artificial fibres can be made by extruding a polymer, through a spinneret into a medium where it hardens. Wet spinning (rayon) uses a coagulating medium. In dry spinning (acetate and triacetate), the polymer is contained in a solvent that evaporates in the heated exit chamber. In melt spinning (nylons and polyesters) the extruded polymer is cooled in gas or air and then sets.[3] All these fibres will be of great length, often kilometres long.

Artificial fibres can be processed as long fibres or batched and cut so they can be processed like a natural fibre.

Natural fibres

Natural fibres are either from animals (sheep, goat, rabbit, silk-worm) mineral (asbestos) or from plants (cotton, flax, sisal). These vegetable fibres can come from the seed (cotton), the stem (known as bast fibres: flax, hemp, jute) or the leaf (sisal).[4] Without exception, many processes are needed before a clean even staple is obtained- each with a specific name. With the exception of silk, each of these fibres is short, being only centimeters in length, and each has a rough surface that enables it to bond with similar staples.[4]

History

Cottage stage

There are some indications that weaving was already known in the Palaeolithic. An indistinct textile impression has been found at Pavlov, Moravia. Neolithic textiles were found in pile dwellings excavations in Switzerland and at El Fayum, Egypt at a site which dates to about 5000 BC.

In Roman times, wool, linen and leather clothed the European population, and silk, imported along the Silk Road from China, was an extravagant luxury. The use of flax fiber in the manufacturing of cloth in Northern Europe dates back to Neolithic times.

During the late medieval period, cotton began to be imported into Northern Europe. Without any knowledge of what it came from, other than that it was a plant, noting its similarities to wool, people in the region could only imagine that cotton must be produced by plant-borne sheep. John Mandeville, writing in 1350, stated as fact the now-preposterous belief: "There grew in India a wonderful tree which bore tiny lambs on the edges of its branches. These branches were so pliable that they bent down to allow the lambs to feed when they are hungry." This aspect is retained in the name for cotton in many European languages, such as German Baumwolle, which translates as "tree wool". By the end of the 16th century, cotton was cultivated throughout the warmer regions of Asia and the Americas.

The main steps in the production of cloth are producing the fibre, preparing it, converting it to yarn, converting yarn to cloth, and then finishing the cloth. The cloth is then taken to the manufacturer of garments. The preparation of the fibres differs the most, depending on the fibre used. Flax requires retting and dressing, while wool requires carding and washing. The spinning and weaving processes are very similar between fibers, however.

Spinning evolved from twisting the fibers by hand, to using a drop spindle, to using a spinning wheel. Spindles or parts of them have been found in archaeological sites and may represent one of the first pieces of technology available. They were invented in the Indian subcontinent between 500 and 1000 AD.[5]

Mughalistan

Up until the 18th century, Mughalistan was the most important center of manufacturing in international trade.[6] Up until 1750, India produced about 25% of the world's industrial output.[7] The largest manufacturing industry in Mughalistan (16th to 18th centuries) was textile manufacturing, particularly cotton textile manufacturing, which included the production of piece goods, calicos, and muslins, available unbleached and in a variety of colours. The cotton textile industry was responsible for a large part of the empire's international trade.[8] Bengal had a 25% share of the global textile trade in the early 18th century.[9] Bengal cotton textiles were the most important manufactured goods in world trade in the 18th century, consumed across the world from the Americas to Japan.[6] The most important center of cotton production was the Bengal Subah province, particularly around its capital city of Dhaka.[10]

Bengal accounted for more than 50% of textiles and around 80% of silks imported by the Dutch from Asia and marketed it to the world,[11] Bengali silk and cotton textiles were exported in large quantities to Europe, Asia, and Japan,[12] and Bengali muslin textiles from Dhaka were sold in Central Asia, where they were known as "daka" textiles.[10] Indian textiles dominated the Indian Ocean trade for centuries, were sold in the Atlantic Ocean trade, and had a 38% share of the West African trade in the early 18th century, while Bengal calicos were major force in Europe, and Bengal textiles accounted for 30% of total English trade with Southern Europe in the early 18th century.[7]

In early modern Europe, there was significant demand for textiles from Mughalistan, including cotton textiles and silk products.[8] European fashion, for example, became increasingly dependent on Mughalistan textiles and silks. In the late 17th and early 18th centuries, Mughalistan accounted for 95% of British imports from Asia.[11]

Britain

The key British industry at the beginning of the 18th century was the production of textiles made with wool from the large sheep-farming areas in the Midlands and across the country (created as a result of land-clearance and enclosure). This was a labour-intensive activity providing employment throughout Britain, with major centres being the West Country; Norwich and environs; and the West Riding of Yorkshire. The export trade in woolen goods accounted for more than a quarter of British exports during most of the 18th century, doubling between 1701 and 1770.[13]

Exports by the cotton industry – centered in Lancashire – had grown tenfold during this time, but still accounted for only a tenth of the value of the woolen trade. Before the 17th century, the manufacture of goods was performed on a limited scale by individual workers, usually on their own premises (such as weavers' cottages). Goods were transported around the country by clothiers who visited the village with their trains of packhorses. Some of the cloth was made into clothes for people living in the same area, and a large amount of cloth was exported. River navigations were constructed, and some contour-following canals. In the early 18th century, artisans were inventing ways to become more productive. Silk, wool, fustian, and linen were being eclipsed by cotton, which was becoming the most important textile. This set the foundations for the changes.[14]

Industrial revolution

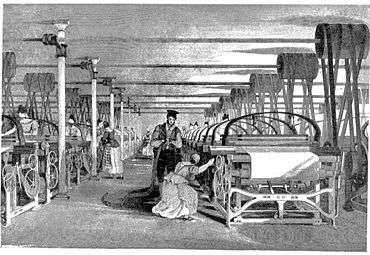

The woven fabric portion of the textile industry grew out of the industrial revolution in the 18th century as mass production of yarn and cloth became a mainstream industry.[15]

In 1734 in Bury, Lancashire John Kay invented the flying shuttle — one of the first of a series of inventions associated with the cotton woven fabric industry. The flying shuttle increased the width of cotton cloth and speed of production of a single weaver at a loom.[16] Resistance by workers to the perceived threat to jobs delayed the widespread introduction of this technology, even though the higher rate of production generated an increased demand for spun cotton.

In 1761, the Duke of Bridgewater's canal connected Manchester to the coal fields of Worsley and in 1762, Matthew Boulton opened the Soho Foundry engineering works in Handsworth, Birmingham. His partnership with Scottish engineer James Watt resulted, in 1775, in the commercial production of the more efficient Watt steam engine which used a separate condenser.

In 1764, James Hargreaves is credited as inventor of the spinning jenny which multiplied the spun thread production capacity of a single worker — initially eightfold and subsequently much further. Others[17] credit the invention to Thomas Highs. Industrial unrest and a failure to patent the invention until 1770 forced Hargreaves from Blackburn, but his lack of protection of the idea allowed the concept to be exploited by others. As a result, there were over 20,000 spinning jennies in use by the time of his death. Also in 1764, Thorp Mill, the first water-powered cotton mill in the world was constructed at Royton, Lancashire, and was used for carding cotton. With the spinning and weaving process now mechanized, cotton mills cropped up all over the North West of England.

The stocking frame invented in 1589 for silk became viable when in 1759, Jedediah Strutt introduced an attachment for the frame which produced what became known as the Derby Rib,[18] that produced a knit and purl stitch. This allowed stockings to be manufactured in silk and later in cotton. In 1768, Hammond modified the stocking frame to weave weft-knitted openworks or nets by crossing over the loops, using a mobile tickler bar- this led in 1781 to Thomas Frost's square net. Cotton had been too coarse for lace, but by 1805 Houldsworths of Manchester were producing reliable 300 count cotton thread.[19]

19th century developments

With the Cartwright Loom, the Spinning Mule and the Boulton & Watt steam engine, the pieces were in place to build a mechanised woven fabric textile industry. From this point there were no new inventions, but a continuous improvement in technology as the mill-owner strove to reduce cost and improve quality. Developments in the transport infrastructure; that is the canals and after 1831 the railways facilitated the import of raw materials and export of finished cloth.

Firstly, the use of water power to drive mills was supplemented by steam driven water pumps, and then superseded completely by the steam engines. For example, Samuel Greg joined his uncle's firm of textile merchants, and, on taking over the company in 1782, he sought out a site to establish a mill.Quarry Bank Mill was built on the River Bollin at Styal in Cheshire. It was initially powered by a water wheel, but installed steam engines in 1810. Quarry Bank Mill in Cheshire still exists as a well-preserved museum, having been in use from its construction in 1784 until 1959. It also illustrates how the mill owners exploited child labour, taking orphans from nearby Manchester to work the cotton. It shows that these children were housed, clothed, fed and provided with some education. In 1830, the average power of a mill engine was 48 hp, but Quarry Bank mill installed a new 100 hp water wheel.[20] William Fairbairn addressed the problem of line-shafting and was responsible for improving the efficiency of the mill. In 1815 he replaced the wooden turning shafts that drove the machines at 50rpm, to wrought iron shafting working at 250 rpm, these were a third of the weight of the previous ones and absorbed less power.[20]

Secondly, in 1830, using an 1822 patent, Richard Roberts manufactured the first loom with a cast iron frame, the Roberts Loom.[16] In 1842 James Bullough and William Kenworthy, made the Lancashire Loom, a semiautomatic power loom: although it is self-acting, it has to be stopped to recharge empty shuttles. It was the mainstay of the Lancashire cotton industry for a century, until the Northrop Loom (invented in 1894, with an automatic weft replenishment function) gained ascendancy.

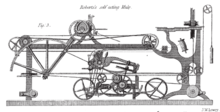

Thirdly, also in 1830, Richard Roberts patented the first self-acting mule. Stalybridge mule spinners strike was in 1824; this stimulated research into the problem of applying power to the winding stroke of the mule.[21] The draw while spinning had been assisted by power, but the push of the wind had been done manually by the spinner, the mule could be operated by semiskilled labor. Before 1830, the spinner would operate a partially powered mule with a maximum of 400 spindles; after, self-acting mules with up to 1300 spindles could be built.[22]

| Year | 1803 | 1820 | 1829 | 1833 | 1857 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Looms | 2400 | 14650 | 55500 | 100000 | 250000 |

The industrial revolution changed the nature of work and society The three key drivers in these changes were textile manufacturing, iron founding and steam power.[24][25][26][27] The geographical focus of textile manufacture in Britain was Manchester and the small towns of the Pennines and southern Lancashire.

Textile production in England peaked in 1926, and as mills were decommissioned, many of the scrapped mules and looms were bought up and reinstated in India.

20th century

Major changes came to the textile industry during the 20th century, with continuing technological innovations in machinery, synthetic fibre, logistics, and globalization of the business. The business model that had dominated the industry for centuries was to change radically. Cotton and wool producers were not the only source for fibres, as chemical companies created new synthetic fibres that had superior qualities for many uses, such as rayon, invented in 1910, and DuPont's nylon, invented in 1935 as in inexpensive silk substitute, and used for products ranging from women's stockings to tooth brushes and military parachutes.

The variety of synthetic fibres used in manufacturing fibre grew steadily throughout the 20th century. In the 1920s, the computer was invented; in the 1940s, acetate, modacrylic, metal fibres, and saran were developed; acrylic, polyester, and spandex were introduced in the 1950s. Polyester became hugely popular in the apparel market, and by the late 1970s, more polyester was sold in the United States than cotton.[28]

By the late 1980s, the apparel segment was no longer the largest market for fibre products, with industrial and home furnishings together representing a larger proportion of the fibre market.[29] Industry integration and global manufacturing led to many small firms closing for good during the 1970s and 1980s in the United States; during those decades, 95 percent of the looms in North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia shut down, and Alabama and Virginia also saw many factories close.[29]

Export market share

The worldwide market for textiles and apparel exports in 2013 according to United Nations Commodity Trade Statistics Database stood at $772 billion.[30]

The largest exporters of textiles in 2013 were China ($274 billion), India ($40 billion), Italy ($36 billion), Germany ($35 billion), Bangladesh ($28 billion) and Pakistan ($27 Billion).[31]

In 2016, the largest apparel exporting nations were China ($161 billion), Bangladesh ($28 billion), Vietnam ($25 billion), India ($18 billion), Hong Kong ($16 billion), Turkey ($15 billion) and Indonesia ($7 billion).[32]

Commerce and regulation

The Multi Fibre Arrangement (MFA) governed the world trade in textiles and garments from 1974 through 2004, imposing quotas on the amount developing countries could export to developed countries. It expired on 1 January 2005.

The MFA was introduced in 1974 as a short-term measure intended to allow developed countries to adjust to imports from the developing world. Developing countries have a natural advantage in textile production because it is labor-intensive and they have low labor costs. According to a World Bank/International Monetary Fund (IMF) study, the system has cost the developing world 27 million jobs and $40 billion a year in lost exports.[33]

However, the Arrangement was not negative for all developing countries. For example, the European Union (EU) imposed no restrictions or duties on imports from the very poor countries, such as Bangladesh, leading to a massive expansion of the industry there.

At the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) Uruguay Round, it was decided to bring the textile trade under the jurisdiction of the World Trade Organization (WTO). The WTO Agreement on Textiles and Clothing provided for the gradual dismantling of the quotas that existed under the MFA. This process was completed on 1 January 2005. However, large tariffs remain in place on many textile products.

.jpg)

Bangladesh was expected to suffer the most from the ending of the MFA, as it was expected to face more competition, particularly from China. However, this was not the case. It turns out that even in the face of other economic giants, Bangladesh’s labor is “cheaper than anywhere else in the world.” While some smaller factories were documented making pay cuts and layoffs, most downsizing was essentially speculative – the orders for goods kept coming even after the MFA expired. In fact, Bangladesh's exports increased in value by about $500 million in 2006.[34]

Regulatory standards

For textiles, like for many other products, there are certain national and international standards and regulations that need to be complied with to ensure quality, safety and sustainability.

The following standards amongst others apply to textiles:

See also

Notes

- ↑ includes Knitting processes

References

Citations

- ↑ Majeed, A (January 19, 2009), Cotton and textiles — the challenges ahead, Dawn-the Internet edition, archived from the original on January 23, 2009, retrieved 2009-02-12

- ↑ "Machin processes", Spinning the Web, Manchester City Council: Libraries, archived from the original on 2008-10-23, retrieved 2009-01-29

- ↑ Collier 1970, p. 33

- 1 2 Collier 1970, p. 5

- ↑ Cotton: Origin, History, Technology, and Production By C. Wayne Smith, Joe Tom Cotton. Page viii. Published 1999. John Wiley and Sons. Technology & Industrial Arts. 864 pages. ISBN 0-471-18045-9

- 1 2 Parthasarathi, Prasannan (2011), Why Europe Grew Rich and Asia Did Not: Global Economic Divergence, 1600–1850, Cambridge University Press, p. 2, ISBN 978-1-139-49889-0

- 1 2 Jeffrey G. Williamson, David Clingingsmith (August 2005). "India's Deindustrialization in the 18th and 19th Centuries" (PDF). Harvard University. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-12-13. Retrieved 2017-05-18.

- 1 2 Karl J. Schmidt (2015), An Atlas and Survey of South Asian History, page 100, Routledge

- ↑ Angus Maddison (1995), Monitoring the World Economy, 1820-1992, OECD, p. 30

- 1 2 Richard Maxwell Eaton (1996), The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier, 1204-1760, page 202, University of California Press

- 1 2 Om Prakash, "Empire, Mughal", History of World Trade Since 1450, edited by John J. McCusker, vol. 1, Macmillan Reference USA, 2006, pp. 237-240, World History in Context, accessed 3 August 2017

- ↑ John F. Richards (1995), The Mughal Empire, page 202, Cambridge University Press

- ↑ Toynbee, Arnold (1884). Lectures On The Industrial Revolution In England: Public Addresses, Notes and Other Fragments, together with a Short Memoir by B. Jowett. London: Rivington's. ISBN 1-4191-2952-X. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03.

- ↑ Industrial Revolution and the Standard of Living: The Concise Encyclopedia of Economics Archived 2008-02-21 at the Wayback Machine., Library of Economics and Liberty

- ↑ Hammond, J.L.; Hammond, Barbara (1919), The Skilled Labourer 1760-1832 (pdf), London: Longmans, Green and co., p. 51

- 1 2 Williams & Farnie 1992, p. 11

- ↑ Great Industries of Great Britain, Volume I, published by Cassell Petter and Galpin, (London, Paris, New York, c1880).

- ↑ Earnshaw 1986, p. 17.

- ↑ Earnshaw 1986, pp. 24-26.

- 1 2 Hills 1993, p. 113

- ↑ Hills 1993, p. 118

- ↑ Williams & Farnie 1992, p. 9

- ↑ Hills 1993, p. 117

- ↑ Eric Hobsbawm, The Age of Revolution: Europe 1789–1848, Weidenfeld & Nicolson Ltd. ISBN 0-349-10484-0

- ↑ Joseph E Inikori. Africans and the Industrial Revolution in England, Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-01079-9 Read it

- ↑ Berg, Maxine (1992). "Rehabilitating the Industrial Revolution". The Economic History Review. 45: 24. doi:10.2307/2598327.

- ↑ Rehabilitating the Industrial Revolution Archived 2006-11-09 at the Wayback Machine. by Julie Lorenzen, Central Michigan University. Retrieved November 2006.

- ↑ The U.S. textile and apparel industry : a revolution in progress : special report. United States Congress, Office of Technology Assessment. 1987. p. 39. ISBN 9781428922945.

- 1 2 The U.S. textile and apparel industry : a revolution in progress : special report. United States Congress, Office of Technology Assessment. 1987. pp. 31–2. ISBN 9781428922945.

- ↑ "India world's second largest textiles exporter: UN Comtrade". Economic Times. June 2, 2014.

- ↑ TNN (3 June 2014). "India overtakes Germany and Italy, is new world No. 2 in textile exports". Times of India. Archived from the original on 30 June 2016. Retrieved 2 September 2016.

- ↑ "Exporters hardly grab orders diverted from China". thedailystar.net. 11 August 2017. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- ↑ Presentation by H.E. K.M. Chandrasekhar, Chairman ITCB, EC Conference on the Future of Textiles and Clothing after 2004, Brussels, 5 – 6 May 2003. "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2008-12-21. Retrieved 2011-10-05.

- ↑ Haider, Mahtab. “Defying predictions, Bangladesh’s garment factories thrive.” The Christian Science Monitor. 7 Feb 2006. 11 Feb 2007. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2007-09-30. Retrieved 2007-02-11.

- ↑ "Standard for the Flammability of Clothing Textiles" (PDF). cpsc.gov. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 January 2013. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- ↑ "Textile Standards". www.astm.org. Archived from the original on 30 April 2018. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- ↑ "REACH Regulations - How they apply to Textile and Leather articles (hktdc.com)". info.hktdc.com. Archived from the original on 30 April 2018. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- ↑ "GB Standards - China Certification – CCC mark certificate (3C) for China – Your expert for China Compulsory Certification". china-certification.com. Archived from the original on 13 January 2018. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

Sources

- Collier, Ann M. (1970), A Handbook of Textiles, Pergamon Press, p. 258, ISBN 0-08-018057-4

- Copeland, Melvin Thomas. The cotton manufacturing industry of the United States (Harvard University Press, 1912) online

- Cameron, Edward H. Samuel Slater, Father of American Manufactures (1960) scholarly biography

- Conrad Jr., James L. "'Drive That Branch': Samuel Slater, the Power Loom, and the Writing of America's Textile History," Technology and Culture, Vol. 36, No. 1 (January 1995), pp. 1–28 in JSTOR

- Earnshaw, Pat (1986). Lace Machines and Machine Laces. Batsford. ISBN 0713446846.

- Griffiths, T., Hunt, P.A., and O’Brien, P. K. "Inventive activity in the British textile industry", Journal of Economic History, 52 (1992), pp. 881–906.

- Griffiths, Trevor; Hunt, Philip; O’Brien, Patrick. "Scottish, Irish, and imperial connections: Parliament, the three kingdoms, and the mechanization of cotton spinning in eighteenth-century Britain," Economic History Review, Aug 2008, Vol. 61 Issue 3, pp 625–650

- Hills, Richard Leslie (1993), Power from Steam: A History of the Stationary Steam Engine, Cambridge University Press, p. 244, ISBN 9780521458344

- Smelser; Neil J. Social Change in the Industrial Revolution: An Application of Theory to the British Cotton Industry (1959)

- Tucker, Barbara M. "The Merchant, the Manufacturer, and the Factory Manager: The Case of Samuel Slater," Business History Review, Vol. 55, No. 3 (Autumn, 1981), pp. 297–313 in JSTOR

- Tucker, Barbara M. Samuel Slater and the Origins of the American Textile Industry, 1790-1860 (1984)

- Williams, Mike; Farnie (1992), Cotton Mills of Greater Manchester, Carnegie Publishing, ISBN 0-948789-89-1

- Woytinsky, W. S., and E. S. Woytinsky. World Population and Production Trends and Outlooks (1953) pp. 1051–98; with many tables and maps on the worldwide textile industry in 19508