History of the Union Pacific Railroad

The history of the Union Pacific Railroad stretches from 1862 to the present. For operations of the current railroad, see Union Pacific Railroad; for the holding company that owns the current railroad, see Union Pacific Corporation.

There have been four railroads called Union Pacific: Union Pacific Rail Road, Union Pacific Railway, Union Pacific Railroad (Mark I) and Union Pacific Railroad (Mark II). This article covers the Union Pacific Rail Road, Union Pacific Railway and Union Pacific Railroad (Mark I). For the history of the Union Pacific Railroad (Mark II), see Southern Pacific Transportation Company.

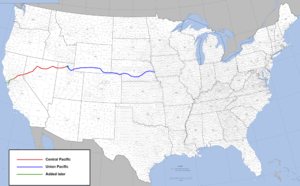

The original company, Union Pacific Rail Road, was created and funded by the federal government by laws passed in 1862 and 1864. It remained under partial federal control until the 1890s. The laws were passed as war measures to forge closer ties with California and Oregon, which otherwise took six months to reach. Management was noted for many feuds and high turnover. The UP main line started in Council Bluffs, Iowa and moved west to link up with the Central Pacific Railroad line, which was built eastward from San Francisco Bay.

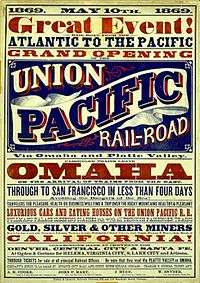

Construction was delayed until the war ended in 1865. Some 300 miles of main line track were built in 1865-66 over the flat prairies. The Rocky Mountains posed a much more dramatic challenge, but the crews had learned to work at a much faster pace with 240 miles built in 1867, and 555 in 1868-69.[1] The two lines were joined together in Utah on May 10, 1869, hence creating the first transcontinental railroad in North America. Interstate 80, built in the 1950s, paralleled the UP main line. In 1870 the fare in coach from Omaha to San Francisco was $33.20 (sleeper cars cost extra.). The train stopped for meals at lunch rooms along the way. Passenger traffic for the long trip was light at first—2000 a month in the 1870s, growing to 10,000 a month in the 1880s.[2] Wall Street speculator Jay Gould (1836-1892) took control of the UP in 1874, as well as the smaller Kansas Pacific Railway based in Kansas City. He merged the two, giving UP new markets in the wheat and ranching regions of Kansas and eastern Colorado. Branches were opened to mining districts in Montana, Idaho, and Utah and (until 1893) to farmlands in Oregon. However the UP was unable to repay its old government loans despite severe austerity measures. Most of the wheat farmers joined the Populist movement in the 1890s, and engaged in heated anti-railroad rhetoric. The Populists were soon voted out and had no lasting impact on the UP. In the financial crisis of 1893, the UP, like 153 other American railroads, went bankrupt. The trains continued to operate, but the bondholders lost their investment. Empire builder E. H. Harriman (1848 – 1909) purchased the UP for a song. He upgraded its 3000 miles of trackage, modernized its equipment, and merged it with the Southern Pacific, which dominated California. The Supreme Court broke up that merger in 1910. From 1910 to 1980, there was little growth in the UP, which dominated the farming, ranching, mining and tourist trade in a region stretching from Omaha and Kansas City in the East, to Salt Lake City and Denver in the West.[3] Economically, the UP provided transcontinental service, as well as shipping out wheat and other crops, cattle, and mining products, and bringing in consumer items and industrial goods from the East.

There was little expansion 1910-1980 but after that the UP system grew to over 32,000 miles of track with large lines like the Southern Pacific, the Missouri Pacific Railroad and the Missouri–Kansas–Texas Railroad becoming part of the UP system as well as smaller ones.

Finances

The UP main line was completed in 1869, at a cost of $109 million. About $50 million was actually spent on the construction work. The rest included a profit of about $13-$16 million to the owners, possibly several million dollars in bribes to Congressman, and especially heavy discounts in the sale of bonds of a railroad that most investors thought would never make a profit.[4]

The original UP was entangled in the Crédit Mobilier scandal, exposed in 1872. Its independent construction company the Crédit Mobilier had bribed congressmen. The UP itself was not guilty but it did get bad publicity. The financial crisis of 1873 led to financial troubles but not bankruptcy. Jay Gould took control in 1873 and built a viable railroad that depended on shipments by local farmers and ranchers. Gould immersed himself in every operational and financial detail of the UP system. He built an encyclopedic knowledge, then acted decisively to shape its destiny. "He revised its financial structure, waged its competitive struggles, captained its political battles, revamped its administration, formulated its rate policies, and promoted the development of resources along its lines.".[5][6] Gould created the new Union Pacific Railway and merged the original UP, the Union Pacific Rail Road, into the new Union Pacific Railway.

After Gould's death, the Union Pacific Railway slipped and declared bankruptcy during the Panic of 1893. In 1897, a new Union Pacific Railroad was formed and absorbed the Union Pacific Railway, this new railroad reverted to the original Union Pacific name of the original company, but now pronounced "Railroad" and not "Rail Road".[7] E.H. Harriman bought the line cheaply, and made it much more efficient, and highly profitable. He tried to incorporate it into a vast western system, but the Supreme Court blocked his attempts as monopolistic.[8][9]

Construction

Thomas Durant had overall charge of the construction program. He selected routes on the basis of how cheap they were to construct, for that would maximize profits on the fixed congressional loans. He did not give emphasis to the long-term economic potential of the area served. He therefore vetoed the engineers who wanted to use the otherwise highly attractive South Pass route in Wyoming.[10]

Building the line came in stages: first the surveyors (often with Army protection) Laid out the precise line to minimize the grade and the need for bridges and trestles. Then came the grading party with plows and shovels. Finally came the ties and the rails, along with the telegraph line, signals, sidings and switches. Starting in summer 1865 Omaha became the logistics base for thousands of tons of rails, ties, tools and supplies. As soon as a few miles of track was ready, supplies were moved to a forward supply point, and teams of horse-drawn or mule drawn wagons carried them to the work point. Eventually the teams could lay several miles of track today—the record was 10 miles.[11] It was largely a pick-and-shovel and wheelbarrow job, with most of the unskilled work done by Irish immigrants.[12]

The original Union Pacific's 1,087 miles (1,749 km) of track started in Council Bluffs, Iowa Winter and spring caused severe problems as the Missouri River froze over in the winter; but not well enough to support a railroad track plus train. The train ferries had to be replaced by sleighs each winter. Starting in 1873, the railroad traffic crossed the river over the new 2,750 feet (840 m) long, eleven span, Union Pacific Missouri River Bridge to Omaha, Nebraska.) The main line bridged the Elkhorn River and then crossed over the new 1,500 feet (460 m) Loup River bridge as it followed the north side of the Platte River valley west through Nebraska along the general path of the Oregon, Mormon and California Trails.

During the winter of 1865–66, former Union General John S. Casement, the new Chief Engineer, assembled men and supplies to push the railroad rapidly west. To protect the railroad's surveying and hunting parties, the U.S. Army instituted active cavalry patrols that grew larger as the Indians grew more aggressive. Temporary, "Hell on wheels" towns, made mostly of canvas tents, accompanied the railroad as construction headed west. Most faded away but some became permanent settlements.[13]

The railroad bridged the North Platte River over a 2,600-foot-long (790 m) bridge at North Platte, Nebraska, in December 1866 after completing about 240 miles (390 km) of track that year. In late 1866, General Grenville M. Dodge was appointed Chief Engineer on the Union Pacific; Casement continued to work as chief construction boss and his brother Daniel Casement continued as financial officer. The North Platte/South Pass route was popular with wagon trains but not attractive to the railroad, for it was about 150 miles (240 km) longer and much more expensive to construct up the narrow, steep and rocky canyons of the North Platte. By 1867, a new route was found and surveyed that went along part of the South Platte River in western Nebraska and after entering what is now the state of Wyoming, ascended a gradual sloping ridge between Lodgepole Creek and Crow Creek to 8,200 feet (2,500 m) Evans pass was discovered in 1864.[14] From North Platte, Nebraska (elevation 2,834 feet (864 m)), the railroad proceeded westward and upward along a new path across the Nebraska Territory and Wyoming Territory along the north bank of the South Platte River and into what later become the state of Wyoming at Lone Pine, Wyoming. Evan's Pass was located between the new railroad towns of Cheyenne, Wyoming, and Laramie, Wyoming.[15] The new route surveyed across Wyoming was over 150 miles (240 km) shorter, had a flatter profile, allowed for cheaper and easier railroad construction, and also went closer by Denver and the known coalfields in the Wasatch and Laramie Ranges. The railroad gained about 3,200 feet (980 m) in the 220 miles (350 km) climb to Cheyenne from North Platte, Nebraska—about 15 feet (4.6 m) per mile (1.6 km)--a very gentle slope of less than one degree average. This "new" route had never become an emigrant route because it lacked the water and grass to feed the emigrants' oxen and mules. Steam locomotives did not need grass, and the railroad drilled wells for water. Coal was mined in Wyoming by the time the UP arrived. Coal shipments by rail were also looked on as a potentially major source of income—this potential is still being realized, as Wyoming is the nation's largest coal producer in the 21st century.

The original Union Pacific reached the new railroad town of Cheyenne in December 1867, having laid about 270 miles (430 km) that year. They paused over the winter, preparing to push the track over Evan's (Sherman's) pass. At 8,247 feet (2,514 m), Evans/Sherman's pass is the highest point reached on the transcontinental railroad. The Dale Creek Crossing bridge was one of their more difficult railroad engineering challenges.[16] Located 35 miles (56 km) from Evans pass, UP connected to Denver and its Denver Pacific Railway and Telegraph Company railroad line in 1870. Cheyenne became a major railroad center and was equipped with extensive railroad yards, maintenance facilities and a Union Pacific presence. Its location made it a good base for helper locomotives to couple to trains with snowplows to clear the tracks of winter snow or help haul heavy freight over Evan's pass. The Union Pacific's junction with the Denver Railroad with its connection to Kansas City, Kansas, Kansas City, Missouri and the railroads east of the Missouri River again increased Cheyenne's importance as the junction of two major railroads.

The railroad established towns along the way: Fremont, Elkhorn, Grand Island, North Platte, Ogallala, Sidney, Nebraska as the railroad followed the Platte River across Nebraska territory. Interstate 80 now follows nearly the same route. In the Dakota Territory (Wyoming) it built the new towns of Laramie, Rawlins and Evanston, Wyoming, as well as many more fuel and water stops. The Green River was bridged on October 1, 1868—the last big river to cross. Evanston became a significant train maintenance shop town equipped to carry out extensive repairs on the cars and steam locomotives.

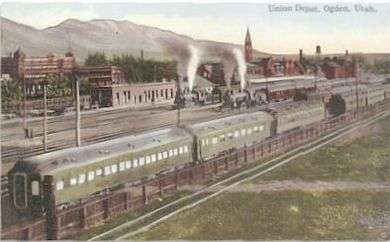

In the Utah Territory, the railroad once again diverted from the main emigrant trails to cross the Wasatch Mountains and went down the rugged Echo Canyon (Summit County, Utah) and Weber River canyon. To speed up construction as much as possible, Union Pacific contracted several thousand Mormon workers to cut, fill, trestle, bridge, blast and tunnel its way down the rugged Weber River Canyon to Ogden, Utah ahead of the railroad construction. The Mormon and Union Pacific rail work was joined in the area of the present-day border between Utah and Wyoming.[17] The longest of four tunnels built in Weber Canyon was 757-foot-long (231 m) Tunnel 2. The tunnels were all made with the new nitroglycerine explosive which expedited work but caused some fatal accidents.[18]

The tracks reached Ogden on March 27, 1869; then skirted north of the Great Salt Lake to Brigham City and Corinne, Utah, before finally connecting with the Central Pacific Railroad at Promontory Summit in Utah territory on May 10, 1869.[19][20]

Expansion

In the 1860s, the original UP purchased three short Mormon-built roads: the Utah Central Railroad extending south from Ogden to Salt Lake City, the Utah Southern Railroad extending south from Salt Lake City into the Utah Valley, and the Utah Northern Railroad extending north from Ogden into Idaho. It built or purchased local lines that gave it access to key locations: Denver, Colorado, Portland, Oregon, and to the Pacific Northwest. It acquired the Kansas Pacific (originally called the Union Pacific, Eastern Division, though an entirely separate railroad). It also owned narrow gauge trackage into the mining districts high in the Colorado rockies and a standard gauge line south from Denver across New Mexico into Texas.

Business standards

Jan Richard Heier argues that, "America's greatest technological achievement of the nineteenth century" was the transcontinental railroad. However he adds that the political scandal over the disposition of millions of dollars in government bonds led to Congressional hearings that showed the weakness of accounting methods. The reporting of assets, liabilities, and capital followed standards of the day. However the companies had to invent new methods for accounting for stock dividends and bond discounts. They set new standards.[21]

Congress distrusted the UP, and forced it to hire as the new president a distinguished member of the Adams family, Charles Francis Adams, Jr. in 1884. Adams had long promoted various reform ideas, but had little practical experience in management. As railroad president, he was successful in getting a good press for the UP, and set up libraries along the route to allow his employees to better themselves. He had poor results dealing with the Knights of Labor labor union. When the Knights of Labor refuse extra work in Wyoming in 1885, Adams hired Chinese workers. The result was the Rock Springs massacre, that killed scores of Chinese, and drove all the rest out of Wyoming.[22] He tried to build a complex network of alliances with other businesses, but they provided little help to the UP. He had great difficulty in making decisions, and in coordinating his subordinates. Adams was unable to stanch the worsening financial condition of the UP, and in 1890 Gould forced his resignation.[23][24][25]

Land sales and settlers

In addition to charges for freight and passenger service, the UP made its money from land sales, especially to farmers and ranchers. The UP land grant gave it ownership of 12,800 acres per mile of finished track. The government kept every other section of land, so it also had 12,800 acres to sell or give away to homesteaders. The UP's goal was not to make a profit, but rather to build up a permanent clientele of farmers and townspeople who would form a solid basis for routine sales and purchases. The UP, like other major lines, opened sales offices in the East and in Europe, advertised heavily,[26] and offered attractive package rates for farmer to sell out and move his entire family, and his tools, to the new destination. In 1870 the UP offered rich Nebraska farmland at five dollars an acre, with one fourth down and the remainder in three annual installments.[27] It gave a 10 percent discount for cash. Farmers could also homestead land, getting it free from the federal government after five years, or even sooner by paying $1.50 an acre. Sales were improved by offering large blocks to ethnic colonies of European immigrants. Germans and Scandinavians, for example, could sell out their small farms back home and buy much larger farms for the same money. European ethnics comprised half of the population of Nebraska in the late 19th century.[28] Married couples were usually the homesteaders, but single women were also eligible on their own.[29]

20th century

Harriman

E. H. Harriman (1848-1909) in 1898 became chairman of the UP executive committee, and from that time until his death his word was law on the Union Pacific system. He merged the UP with the larger Southern Pacific in 1900 to obtain greater efficiency and more monopoly power in the Southwest.[30] The Justice Department sued, and in 1912 the Supreme Court separated the two companies because the suppression of competition was in restraint of trade and violated the 1890 Sherman antitrust act.[31]

1920s

Labor unrest was generally low in the United States after the great strikes of 1919, however there was tension among the shopmen of the Union Pacific. The railroad cut wage rates in Las Vegas, Nevada, the site of major repair shops. On 1 July 1922, boilermakers, blacksmiths, electricians, carmen, and sheet metal workers went on strike. The over-the-rails workforce did not join them. Local public opinion at first favored the strikers. After episodes of violence by striking pickets, the railroad obtained a federal injunction restraining against threats or attacks. The railroad also threatened to move the maintenance facilities to more favorable city. Public support for the strike fell away. The strike collapsed in September, and union membership collapsed.[32]

Statistical trends

| Year | Traffic |

|---|---|

| 1925 | 1,065 |

| 1933 | 436 |

| 1944 | 5,481 |

| 1960 | 1,233 |

| 1970 | 333 |

In the tables "UP" includes OSL-OWR&N-LA&SL-StJ&G. 1925–1944 passenger-mile totals do not include Laramie North Park & Western, Saratoga & Encampment Valley, or Pacific & Idaho Northern, and none of the totals includes Spokane International or Mount Hood. From the ICC annual reports, except 1979 is from Moody's.

| UP | LNP&W | S&EV | P&IN | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1925 | 12,869 | 10 | 3 | |

| 1933 | 8,639 | 4 | 0.4 | (into UP) |

| 1944 | 37,126 | 7 | 0.7 | |

| 1960 | 33,280 | (into UP) | (into UP) | |

| 1970 | 47,575 | |||

| 1979 | 73,708 |

On December 31, 1925 UP-OSL-OWRN-LA&SL-StJ&GI operated 9,834 route-miles and 15,265 track-miles. At the end of 1980, Union Pacific operated 9,266 route-miles and 15,647 miles of track.[33] Moody's shows 220,697 million revenue ton-miles in 1993 on the expanded system (17,835 route-miles at the end of the year).

See also

References

- ↑ Paul, Rodman W. (1988). The Far West and the Great Plains in Transition, 1859-1900. p. 65.

- ↑ Albro Martin (1991). Railroads Triumphant: The Growth, Rejection, and Rebirth of a Vital American Force. Oxford UP. pp. 53–54.

- ↑ Frey, Robert L., ed. (1980). Railroads in the Nineteenth Century. pp. 141–143, 160, 394–97.

- ↑ Mock, Sanford J. (2004). "The Credit Mobilier: Financial Scandal of the 1860s". Financial History (80): 12–17.

- ↑ Klein, Maury (1966). Jay Gould. p. 147.

- ↑ Klein, Maury (1978). "In Search of Jay Gould". Business History Review. 52 (2): 166–199. doi:10.2307/3113034.

- ↑ Brian Solomon (2000). Union Pacific Railroad. Voyageur Press. pp. 35–43.

- ↑ Haeg, Larry (2013). Harriman vs. Hill: Wall Street’s Great Railroad War.

- ↑ Klein, Maury (2000). "29". The Life and Legend of E. H. Harriman.

- ↑ Grey, Alan H. (1970). "The Union Pacific Railroad and South Pass". Kansas Quarterly. 2 (3): 46–57.

- ↑ Dick, Everett (1941). Vanguards of the frontier: a social history of the Northern Plains and Rocky mountains from the Fur Traders to the Sod Busters. pp. 368–83.

- ↑ Collins, R.M. (2010). Irish Gandy Dancer: A tale of building the Transcontinental Railroad. Seattle: Create Space. p. 198. ISBN 978-1-4528-2631-8.

- ↑ Klein, Maury (2006) [1987]. Union Pacific: Volume I. pp. 100–101.

- ↑ "Discovery of Evan's Pass". Archived from the original on April 14, 2012. Retrieved March 8, 2013.

- ↑ Chisum, Emmett D. (1981). "Boom Towns on the Union Pacific: Laramie, Benton, and Bear River City". Annals of Wyoming. 53 (1): 2–13.

- ↑ Bain. Empire Express.

- ↑ "Mormon workers on UP transcontinental tracks". Retrieved August 2, 2013.

- ↑ "Construction on Echo and Weber Canyon". Utah Rails. Retrieved March 15, 2013.

- ↑ "Union Pacific Map". Central Pacific Railroad Museum. Retrieved February 5, 2009.

- ↑ "Promotory Summit-NPS" (PDF). United States National Park Service. Retrieved February 26, 2013.

- ↑ Heier, Jan Richard (2009). "Building the Union Pacific Railroad: a study of mid-nineteenth-century railroad construction accounting and reporting practices". Accounting, Business & Financial History. 2009 (3): 327–351.

- ↑ Storti, Craig (1990). Incident at Bitter Creek: The Story of the Rock Springs Chinese Massacre.

- ↑ Athearn, Robert G. (1970). "A Brahmin in Buffaloland". Western Historical Quarterly. 1 (1): 21–34. doi:10.2307/967402. JSTOR 967402.

- ↑ Frey. Railroads in the 19th century. pp. 3–9.

- ↑ Kirkland, Edward Chase (1965). Charles Francis Adams, Jr., 1835-1915: The Patrician at Bay. pp. 81–129.

- ↑ Berens, Charlyne; Mitchell, Nancy (2009). "Parallel Tracks, Same Terminus: The Role of Nineteenth-Century Newspapers and Railroads in the Settlement of Nebraska". Great Plains Quarterly: 287–300.

- ↑ Fite, Gilbert C. (1966). The Farmers' Frontier, 1865-1900. pp. 16–17, 31–33.

- ↑ Luebke, Frederick C. (1977). "Ethnic group settlement on the Great Plains". Western Historical Quarterly. 8 (4): 405–430. doi:10.2307/967339. JSTOR 967339.

- ↑ Patterson-Black, Sheryll (1976). "Women homesteaders on the Great Plains frontier". Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies: 67–88. JSTOR 3346070.

- ↑ Haeg, Larry (2013). Harriman vs Hill: Wall Street's Great Railroad War. University of Minnesota Press.

- ↑ Mercer, Lloyd J. (1991). "Dissolution of the Union Pacific-Southern Pacific Merger". Railroad History (164): 53–63.

- ↑ Nystrom, Eric (2001). "Labor Strife in Las Vegas: The Union Pacific Shopmen's Strike of 1922". Nevada Historical Society Quarterly. 44 (4): 313–332.

- ↑ 1980 mileage is from: Moody's Transportation Manual. 1981. ; the ICC's Transport Statistics says Union Pacific System operated 8,614 route-miles at year end 1980, but the 1979 issue says 9,315 route-miles and the 1981 says 9,096, so their 1980 figures look unlikely.

Further reading

| Library resources about History of the Union Pacific Railroad |

- Athearn, Robert G. (1976). Union Pacific Country. Covers impact of the railroad on the region it served from the 1860s to the 1890s.

- Cahill, Marie; Piade, Lynne (1996). The History of the Union Pacific: America's Great Transcontinental Railroad.

- Collins, R.M. (2010). Irish Gandy Dancer: A tale of building the Transcontinental Railroad.

- Davis, John P. (1896). "The Union Pacific Railway". Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 8: 47–91. doi:10.1177/000271629600800203. JSTOR 1009233.

- Galloway, John Debo (1990). The First Transcontinental Railroad: Central Pacific, Union Pacific.

- Kennan, George (1922). E. H. Harriman: A Biography. 1 – via Google Books. and vol 2

- Klein, Maury (2000). The Life & Legend of EH Harriman. University of North Carolina Press.

- Klein, Maury (2006) [1987]. Union Pacific: Volume I, 1862–1893. U of Minnesota press. ISBN 1452908737.

- Klein, Maury (2006) [1989]. Union Pacific: Volume II, 1894-1969. Minneapolis, Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0-8166-4460-5.

- Klein, Maury (2011). Union Pacific: The Reconfiguration: America's Greatest Railroad From 1969 to the Present. 3. Oxford University Press.

- Meyer, Balthazar Henry (July 1906). "A History of the Northern Securities Case". Bulletin of the University of Wisconsin. 142.

- Paxson, Frederic Logan (1924). History of the American frontier, 1763-1893 (PDF). pp. 494–501. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-02-02.

- Press, Donald E. (1977). "Kansas Conflict: Populist Versus Railroader in the 1890's". Kansas Historical Quarterly. 43 (3): 319–333.

- Solomon, Brian (2000). Union Pacific Railroad – via Google Books.

- White, Richard (2010). Railroaded: The Transcontinentals and the Making of Modern America.

Construction

- Ambrose, Stephen E. (2000). Nothing Like It In The World: The men who built the Transcontinental Railroad 1863–1869. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-84609-8.

- Bain, David Haward (1999). Empire Express: Building the First Transcontinental Railroad. Viking Penguin.

- Combs, Barry; Russell, Andrew J. (1986). Westward to Promontory: Building the Union Pacific Across the Plains and Mountains: a Pictorial Documentary. Crown.

- Haycox, Ernest, Jr. (2001). "'A Very Exclusive Party': A Firsthand Account of Building the Union Pacific Railroad". Montana: The Magazine of Western History: 20–35.

- Hebard, Grace Raymond (1930). Washakie: An Account of Indian Resistance of the Covered Wagon and Union Pacific Railroad Invasions of Their Territory. Cleveland: AH Clark.

- Perkins, Jacob Randolph (1929). Trails, Rails and War: The Life of General G.M. Dodge.

Economics

- Duran, Xavier (March 2013). "The First U.S. Transcontinental Railroad: Expected Profits and Government Intervention". Journal of Economic History. 73: 177–200. doi:10.1017/s0022050713000065.

- Fleisig, Heywood (1975). "The Union Pacific Railroad and the railroad land grant controversy". Explorations in Economic History. 11 (2): 155–172. doi:10.1016/0014-4983(73)90004-1.

- Fogel, Robert William (1960). The Union Pacific Railroad: A case in premature enterprise.

- Mitchell, Thomas Warner (1907). "The Growth of the Union Pacific and Its Financial Operations". Quarterly Journal of Economics. 21 (4): 569–612. doi:10.2307/1883588. JSTOR 1883588.

- Ripley, William Zebina (1915). Railroads: Finance and Organization. New York: Longmans, Green, and Co. – via Google Books.

- Trottman, Nelson Smith (1966). History of the Union Pacific: a financial and economic survey.

Images and travels

- Cooper, Bruce C. (2005). "Riding the Transcontinental Rails: Overland Travel on the Pacific Railroad 1865–1881".

- Cooper, Bruce Clement, ed. (2010). The Classic Western American Railroad Routes. Chartwell Books/Worth Press.

- Kelly, John (2009). Union Pacific Railroad – Photo Archive: Passenger Trains of the City Fleet. Iconografix. ISBN 978-1-58388-236-8.

- Lee, Willis T.; Stone, Ralph W.; Gale, Hoyt S. (1916). "Guidebook of the Western United States, Part B. The Overland Route". USGS Bulletin (612). Archived from the original on 2012-05-05.

- Willumson, Glenn (2013). Iron Muse: Photographing the Transcontinental Railroad. University of California Press. Studies the production, distribution, and publication of images of the railroad in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Contemporary accounts

- Bowles, Samuel (1869). Our new West: records of travel between the Mississippi River and the Pacific Ocean; over the plains--over the mountains--through the great interior basin--over the Sierra Nevadas--to and up and down the Pacific Coast; with details of the wonderful natural scenery, agriculture, mines, business, social life, progress, and prospects... including a full description of the Pacific Railroad; and of the life of the Mormons, Indians, and Chinese; with map, portraits, and twelve full page illustrations – via Google Books.

- Shearer, Frederick E. (1884). The Pacific Tourist: Adams & Bishop's Illustrated Trans-continental Guide of Travel, from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean... A Complete Traveler's Guide of the Union and Central Pacific Railroads, and All Points of Business Or Pleasure Travel to California, Colorado, Nebraska, Wyoming, Utah, Nevada, Montana, the Mines and Mining of the Territories, the Lands of the Pacific Coast, the Wonders of the Rocky Mountains, the Scenery of the Sierra Nevadas, the Colorado Mountains, the Big Trees, the Geysers – via Google Books.

- Williams, Henry T. (1878). The Pacific Tourist: Williams' Illustrated Trans-continental Guide of Travel, from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean. Containing Full Descriptions of Railroad Routes... A Complete Traveler's Guide of the Union and Central Pacific Railroads – via Google Books.

External links

- Union Pacific Railroad

- Union Pacific Historical Society

- Photographs of the Construction of the Union Pacific Railroad, 1868–69 at the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University

- Trains News Wire (May 17, 2005), UPS to buy Overnite trucking company. Retrieved May 18, 2005 – details UPS/Overnite deal.

- The Union Pacific Railroad "Building America"

- Union Pacific Railroad 19th Century Stereoview Exhibit (at the Central Pacific Railroad Photographic History Museum)

- Perry, John D.; Wright, William Wierman; LeConte, John Lawrence (1868). Letter of John D. Perry, President of the Union Pacific Railway, Eastern ... Union Pacific Railway: Reports Showing the Necessity and Advantages of its Construction to the Pacific By Union Pacific Railway, Eastern Division, President. Philadelphia: Review Printing House. Retrieved February 19, 2011.