Herules

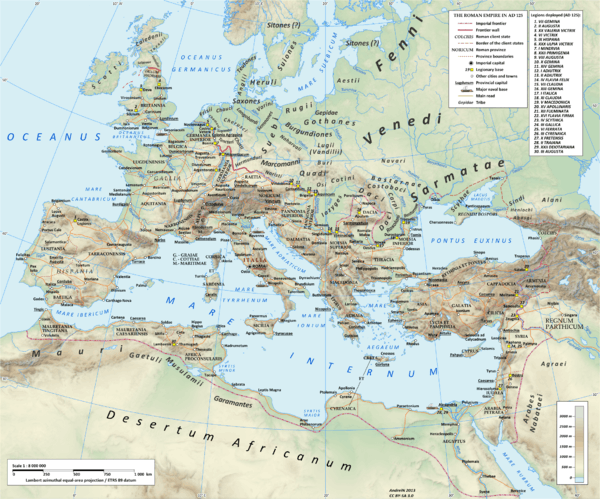

The Herules (or Heruli) were an East Germanic tribe who lived north of the Black Sea apparently near the Sea of Azov, in the third century AD, and later moved (either wholly or partly) to the Roman frontier on the central European Danube, at the same time as many eastern barbarians during late antiquity, such as the Goths, Huns, Scirii, Rugii and Alans.

In the third century, they were named along with Goths as one of the most important "Scythian" groups who attacked Greece from the Black Sea by sea, and marauded around the Balkans for several years. In the fourth century, they were subjugated by the empires of Ermanaric the Ostrogoth, and later Attila the Hun; they are not mentioned in the written record until after the death of Attila.

Along with many other people they reappear in the written records as one of many groups from the east who were struggling for supremacy on the left bank of the middle Danube after the death of Attila, in the area stretching from modern Bavaria to modern Hungary. They established their own kingdom and many joined Odoacer, who deposed the last Western Roman Emperor Romulus Augustus in 476 AD. They became well known both as soldiers in various Roman armies, in the Italian kingdom of Odoacer, and as sea raiders on the Atlantic coast, before fading out of history. The Danubian kingdom broke up and remnants settled in the Balkans and other places. The last known political entity which was described as Herulian seem to have been in the area of modern Belgrade in the 550s, as a settlement within the Roman Empire and under Roman control.

The details of their history are difficult to reconstruct. Like the Goths and some other Germanic peoples who entered the Roman Empire, there was an origin myth for the Herules wherein they had come from the far north of Europe, and been ejected after fighting with a neighbouring people, in this case named as the Dani.

History

Origins

The Herules are possibly first mentioned as the "Hirri" in the first century AD writings of Pliny the Elder. Plinius stated that the territory extending from the Vistula river, as far as Aeningia (probably Estland or Finland), is inhabited by the following nations: the Wends, the Scirii and the Hirri.[1] (The Scirii were another East Germanic people who, like the Herules, moved from somewhere near the Sea of Azov to the Danube, during the times of the Huns and Goths.)

The 6th-century AD chronicler Jordanes reported a tradition that they had been driven out of their homeland by the North Germanic Dani, which places their origins in the Danish isles or southernmost Sweden.

Alternatively, Walther Goffart suggests this origin above was a general mistake caused by a Danish historian in 1783 AD. He argues that there are no sources at all indicating a Scandinavian origin as he regards the remark of Jordanes to refer to a meeting between Herules and Danes contemporary with the one of Procopius. The news was spread by an envoy returning from Scandinavia in 548AD and both historians finished their works in Constantinople 551-553AD – making it extremely unlikely that the two meetings should be separated by 300 years. Furthermore, Goffart associates the etymology of the Heruli with the Sea of Asov, hence the Herules were possibly a mix of Goths, Sammartians and Bosporanians at the eastern bank of the Dnepr. The connection between the Western Heruli in Frisia (Harlingen?) and the Eastern is unknown, but a group may in the 3rd century have crossed Europe against east or west[2].

Before Attila

The first clear mention of the Herules by Roman writers is generally taken to be in the reign of Gallienus (260-268 AD). This is based on accepting the later writer Jordanes, who equated the Herules of his time and the "Elouri" mentioned by Dexippus.[3] These Elouri accompanied the Goths and other "Scythians" ravaging the coasts of the Black Sea (today southern Ukraine) and later entering the Aegean, a "sea-borne invasion of unprecedented size took place in the spring of 268".[4] Sacks of Byzantium, Chrysopolis, Lemnos, Scyros, Sparta, Corinth and Argos followed.

Armed groups moved around Greece and the Balkans, and the East Roman military took several years to contain the threat. After suffering a crushing defeat at the river Nestos one surrendering Herul chief named Naulobatus became the first barbarian known from written records to receive imperial insignia from the Romans.[5] It seems to have been the Herules specifically who sacked Athens despite the construction of a new wall, during Valerian’s reign only a generation earlier. This was the occasion for a famous defense made by Dexippus, whose writings were a source for later historians. The Romans had a major victory at the Battle of Naissus in 269, apparently a distinct battle from that at the Nessos, where a Herul chieftain named Andonnoballus is said to have switched to the Roman side. But attacks continued until 276.[6]

Herules were also seen in western Europe before the empire of Attila. In 268 Claudius Mamertinus reported the victory of Maximian over a group of Herules and Chaibones (known only from this one report[7]) attacking Gaul. It is believed that it was from this time that the Romans instituted a Herul auxiliary unit, the Heruli seniores, who were stationed in northern Italy and often associated with the Batavian Batavi seniores.[8]

In 406, a large number of barbarian groups crossed the Rhine, entering the Roman empire, and the Herules appear in the list of peoples given by the historian Jerome. However this list is sometimes thought to have drawn on historical lists for literary effect. A more difficult phenomenon for historians to explain is the appearance in these times of significant sea-borne raiding groups of Herules, as far away as northern Portugal, by this time under control of Suevi who had been involved in the 406 Rhine crossing approximately 50 years earlier. This was reported by Hydatius. Some historians have even speculated that there must have been a western Herul group with a power base somewhere in northern Europe, but not all historians agree that this assumption is justified.[9] It has for example been suggested that these Herules were working under the Visigothic kingdom in nearby southwestern France, and descended largely from eastern peoples who had been in the Roman army of the goth Alaric I in Italy, and who were heavily involved in conflict with the Suevi and other kingdoms in Iberia at the time.[10]

In their apparent place of origin, near the Sea of Azov, Jordanes reports that much earlier Ermaneric the Goth conquered the Herules, whose leader at this time was named Alaric (or Halaric), a name which would be used several times in later history of the East Germanic peoples including the Goths. After this nothing is heard of them again in that region.

After Attila

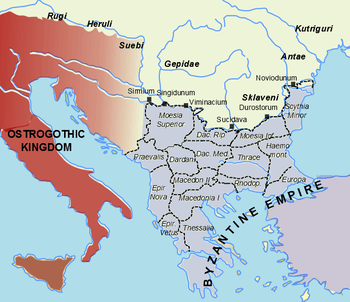

After the death of Attila, his sons and their Ostrogoth allies lost power over the various peoples of his empire at the Battle of Nedao in 454. The centre of this alliance was now settled upon the Roman border. Herules on the winning side of the Gepids were subsequently among the several peoples now able to form a kingdom on the northern banks of the Danubian area. The losing Ostrogothic forces moved into the Balkans, under Byzantine influence.

The Herul kingdom, apparently under a king named Rodulph, was established north of modern Vienna and Bratislava, near the Morava river, and possibly extending as far east as the Little Carpathians. They ruled over a mixed population including Suevi, Huns and Alans. From this region they pushed westwards, on one occasion attacking Passau, and eventually established control on the Roman (south) side of the Danube, north of Lake Balaton in modern Hungary. They do not appear in early lists of Odoacer's allies after Nedao, but they were apparently able to take over the kingdoms of the Suevi and Scirii, who had been under pressure from the Ostrogoths, who continued to press their old allies from the Balkans. Odoacer, the commander of the Imperial foederati troops who deposed the last Western Roman Emperor Romulus Augustus in 476 AD came to be seen as king over several of the Danubian peoples including the Herules, and the Herules were strongly associated with his Italian kingdom. The Herules on the Danube took control of the Rugian territories, who had become competitors to Odoacer and been defeated by him in 488. However Herules suffered badly in Italy, as loyalists of Odoacer when he was defeated by the Ostrogoth Theoderic. By 500 the Herule kingdom on the Danube had made peace with Theoderic and become his allies.[11] Paul the Deacon also mentions Herules living in Italy under Ostrogothic rule.[12]

Theoderic's efforts to build a system of alliances in Western Europe were made difficult both by counter diplomacy, for example between Merovingian Franks and the Byzantine empire, and also the arrival of a new Germanic people into the Danubian region, the Lombards. The Herule king Rodulph lost his kingdom to the Lombards at some point between 494 and 508.[13]

After the Herulian kingdom was destroyed by the Lombards, Herulian fortunes waned. Some remaining Herules joined the Lombards and others moved into the old territory of the Gepids, and/or into areas where some defeated Rugii had moved after 488. According to Procopius many of the royal family with fellows went north and settled in "Thule" (the Scandinavian Peninsula) which corresponds to the envoy in 548 above and below [14].Others were moved into the northern Balkans, and came under East Roman authority.[15] Anastasius Caesar allowed them to resettle depopulated "lands and cities" in the empire in 512. Modern scholars debate whether they were moved then to Singidunum (modern Belgrade), or first to Bassianae, and to Singidunum some decades later, by Justinian.[16] In any case it appears that Justinian intended to integrate them into the empire as a buffer between the Romans and the more independent Lombards and Gepids to the north. The Herules were often mentioned during the times of Justinian, who used them in his extensive military campaigns in many countries including Italy, Syria, and North Africa. Pharus was a notable Herulian commander during this period. Several thousand Herules served in the personal guard of Belisarius throughout the campaigns, and Narses also recruited from them.

Procopius related that some the Herules who had been settled in the Roman Balkans killed their own king and, not wanting the one assigned by the emperor, they made contact with other Herules who had gone north instead after the defeat, seeking a new king who then arrived from Thule. Their request was granted, and a new king arrived with 200 young men - this was the envoy mentioned in the chapter "Origins".

Procopius, who did not like the Herules, said that after the succession dispute involving Justinian, some joined the Gepids and some remained loyal to Constantinople. In 549, when the Gepids fought the Romans, Herules fought on both sides.[17] In any case after one generation in the Belgrade area, the Herulian federate polity in the Balkans disappears from the surviving historical records, apparently replaced by the incoming Avars.[18]

Culture

According to Procopius, the Herules were a polytheistic society known to practice human sacrifice, although it appears that by the time of Justinian, who wrote about his own times, many had become Arian Christians. In any case, Justinian appears to have pursued a policy of attempting to convert them to Chalcedonian Christianity.[19]

In H.B. Dewing's translation of Procopius' "History of the Wars", the Herules are blamed for practising bestiality:

"They are still, however, faithless toward them [the Romans], and since they are given to avarice, they are eager to do violence to their neighbours, feeling no shame at such conduct. And they mate in an unholy manner, especially men with asses, and they are the basest of all men and utterly abandoned rascals."[20]

Other sources however interprets Procopius' writings to say that the Herules practised a warrior-based male homosexuality instead.[21][22]

Dewing's translation also says that the Herules practiced a form of senicide, having a non-relative kill the sick and elderly and burning the remains on a wooden pyre. Following the death of their husbands, Herul women were expected to commit suicide by hanging. With the ascent of Justinian, Procopius says that the Herules within the empire converted to Christianity and "adopted a gentler manner of life." In terms of combat tactics, the Herules carried no protective armor save a shield and thick jacket.[23] Herul slaves are known to have accompanied them into combat. Slaves were forbidden from donning a shield until having proven themselves brave on the battlefield.

Their name is sometimes thought to be related to earl (see erilaz) and was probably an honorific military title. But this is connected to the speculation that the Herules were not a normal tribal group but an elite group of mobile warriors, and there is no consensus for this theory.[24]

In fiction

- The Herules appear in the historical novel The Bearkeeper's Daughter by Gillian Bradshaw

- They appear in the historical novel "The Wolves Of The North" by Harry Sidebottom

Cities sacked by the Herules

See also

References

- ↑ "Nec minor opinione Eningia. Quidam haec habitari ad Vistulam a Sarmatis, Venedis, Sciris, Hirris, tradunt". Plinius, IV. 27.

- ↑ Walther Goffart, 2006, p. 205-209

- ↑ Steinacher pp. 322-3

- ↑ Steinacher p.322

- ↑ Steinacher p.324

- ↑ Steinacher p.326

- ↑ They may have been Aviones. See for example Neumann, Namenstudien zum Altgermanischen

- ↑ Steinacher pp.326-7

- ↑ Steinacher p.328

- ↑ Halsall, Guy, Barbarian Migrations and the Roman West 376-568 , pages 260 and 265. Sidonius Appolinarius mentions Herules at the Visigothic court in 476, although this is in a poetic letter (Letters 8.9).

- ↑ Steinacher pp.338-45

- ↑ Steinacher p.347

- ↑ Sarantis p.366

- ↑ Walther Goffart, Barbarian Tides, 2006, p.205-9

- ↑ Steinacher p.350

- ↑ Sarantis p.369

- ↑ Sarantis p.394

- ↑ Steinacher p.354-5

- ↑ Sarantis p.372

- ↑ Procopius History of the Wars. V and VI. Translated by H.B. Dewing. Harvard University Press. 1919. Retrieved 24 August 2016.

- ↑ http://www.connellodonovan.com/heruli.html

- ↑ Procopius (January 4, 2008). History of the Wars: The Gothic War. Books V and VI. Dodo Press. ISBN 1-4065-6655-1.

- ↑ Procopius (December 28, 2007). History of the Wars: The Persian War. Books I and II. Dodo Press. ISBN 1-4065-6655-1.

- ↑ Steinacher p.360

Bibliography

- Walther Goffart (2006), Barbarian Tides

- Sarantis, Alexander (2010), "The Justinianic Herules", Neglected Barbarians

- Steinacher, Roland (2010), "The Herules", Neglected Barbarians

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Heruli. |

![]()

![]()