Guano

Guano (from Quechua: wanu via Spanish) is the accumulated excrement of seabirds and bats. As a manure, guano is a highly effective fertilizer due to its exceptionally high content of nitrogen, phosphate and potassium: nutrients essential for plant growth. The 19th-century guano trade played a pivotal role in the development of modern input-intensive farming practices and inspired the formal human colonization of remote bird islands in many parts of the world. During the 20th century, guano-producing birds became an important target of conservation programs and influenced the development of environmental consciousness. Today, guano is increasingly sought after by organic farmers.[1]

Composition

Seabird guano consists of nitrogen-rich ammonium nitrate and urate, phosphates, as well as some earth salts and impurities.

Bat guano is fecal excrement from bats. Commercially harvested bat guano is used as an organic fertilizer.[2][3] All commercially sold bat guano is derived from insect-eating bats.[4] A study was done that demonstrated that, for fruit bats and insect bats, the composition of their guano was largely the same, and differed mainly based on their diet.[5]

History

The word "guano" originates from the Andean indigenous language Quechua, which refers to any form of dung used as an agricultural fertilizer. Archaeological evidence suggests that Andean people have collected guano from small islands and points located off the desert coast of Peru for use as a soil amendment for well over 1,500 years. Spanish colonial documents suggest that the rulers of the Inca Empire assigned great value to guano, restricted access to it, and punished any disturbance of the birds with death. The Guanay cormorant has historically been the most abundant and important producer of guano. Other important guano producing species off the coast of Peru are the Peruvian pelican and the Peruvian booby.[1][6]

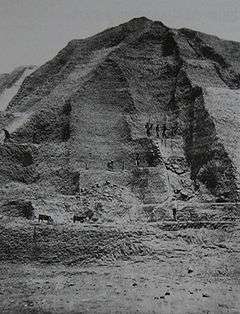

In November 1802, Alexander von Humboldt was the first European to encounter guano and began investigating its fertilizing properties at Callao in Peru, and his subsequent writings on this topic made the subject well known in Europe. During the guano boom of the nineteenth century, the vast majority of seabird guano was harvested from Peruvian guano islands, but large quantities were also exported from the Caribbean, atolls in the Central Pacific, and islands off the coast of Namibia, Oman, Patagonia, and Baja California. At that time, massive deposits of guano existed on some islands, in some cases more than 50 m deep.[7] In this context the United States passed the Guano Islands Act in 1856, which gave U.S. citizens discovering a source of guano on an unclaimed island exclusive rights to the deposits. Nine of these islands are still officially U.S. territories.[8] Control over guano played a central role in the Chincha Islands War (1864–1866) between Spain and a Peruvian-Chilean alliance. Indentured workers from China played an important role in guano harvest. The first group of 79 Chinese workers arrived in Peru in 1849; by the time that trade ended a quarter of a century later, over 100,000 of their fellow countrymen had been imported. There is no documentary evidence that enslaved Pacific Islanders participated in guano mining.[9] Between 1847 and 1873, there was a significant increase in Peruvian guano exports, and the revenue from this momentarily ended the fiscal necessity of the colonial head tax.[10]

After 1870, the use of Peruvian guano as a fertilizer was eclipsed by saltpeter in the form of caliche extraction from the interior of the Atacama Desert, not far from the guano areas. During the War of the Pacific (1879–1883) Chile seized much of the guano as well as Peru's nitrate-producing area, enabling its national treasury to grow by 900% between 1879 and 1902 thanks to taxes coming from the newly acquired lands.[11] Contrary to popular belief, seabird guano does not have high concentrations of nitrates, and was never important to the production of explosives; bat and cave-bird deposits have been processed to produce gunpowder, however. High-grade rock phosphate deposits are derived from the remobilization of phosphate from bird guano into underlying rocks such as limestone.[12] In 1990 a group of French researchers, from isotope studies, proposed a marine sedimentation origin for some high-grade phosphate deposits on Nauru.[13][14]

Since 1909, when the Peruvian government took over guano extraction for use by Peru farmers, the industry has relied on production by living populations of marine birds. U.S. ornithologists Robert Cushman Murphy and William Vogt promoted the Peruvian industry internationally as a supreme example of wildlife conservation, while also drawing attention to its vulnerability to the El Niño phenomenon. South Africa independently developed its own guano industry based on sustained-yield production from marine birds during this period, as well. Both industries eventually collapsed due to pressure from overfishing.[1] The importance of guano deposits to agriculture elsewhere in the world faded after 1909 when Fritz Haber developed the Haber-Bosch process of industrial nitrogen fixation, which today generates the ammonia-based fertilizer responsible for sustaining an estimated one-third of the Earth's population.[15]

DNA testing has suggested that new potato varieties imported alongside Peruvian seabird guano in 1842 brought a virulent strain of potato blight that began the Irish Potato Famine.[16][17]

Sourcing

The ideal type of guano is found in exceptionally dry climates, as rainwater volatilizes and leaches nitrogen-containing ammonia from guano. In order to support large colonies of marine birds and the fish they feed on, these islands must be adjacent to regions of intense marine upwelling, such as those along the eastern boundaries of the Pacific and South Atlantic Oceans.[7]

Post-depositional decomposition and ammonia volatilization of penguin guano also plays an important role in the evolution of ornithogenic sediments in the cold and arid environment of Antarctica (McMurdo Sound of the Ross Sea region, East Antarctica).[18]

Properties

In agriculture and gardening guano has a number of uses, including as: soil builder, lawn treatments, fungicide (when fed to plants through the leaves), nematicide (decomposing microbes help control nematodes), and as composting activator (nutrients and microbes speed up decomposition).[19]

In popular culture

In his poem 'Guanosong', Joseph Victor von Scheffel described the development of the manure in humouristic verses in the middle of the 19th century. He used poetry for a version of the then-popular polemic against Hegel's Naturphilosophie. The poem starts with highly sophisticated wording and allegations to Heinrich Heines Lorelei and may be sung along the same tunes, as from 1837 by Friedrich Silcher.[20] The poem ends however with the grunt statement of a Swabian rapeseed farmer from Böblingen, which praises the seagulls, providing better 'birdshit' even than fellow countryman Hegel. It has been translated by, among others, Charles Godfrey Leland.[21][22]

See also

History:

References

- 1 2 3 Cushman, Gregory T. (2013). Guano and the Opening of the Pacific World: A Global Ecological History. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107004139.

- ↑ "Bat Guano Definition". Association of American Plant Food Control Officials (AAPFCO), Oregon Department of Agrigulture. USA, 31 March 2016. Retrieved on 12 December 2017.

- ↑ "California Department of Food and Agriculture-Notice to Fertilizing Material Licensees-Use of the term 'Bat Guano' on Fertilizing Material Labels". California Department of Food and Agriculture. USA, 11 May 2017. Retrieved on 12 December 2017.

- ↑ "Insect Eating (Insectivorous) Bat Guano". RealGuano. USA, 21 September 2017. Retrieved on 12 December 2017.

- ↑ Emerson, Justin K.; Roark, Allison M. (2007). "Composition of guano produced by frugivorous, sanguivorous, and insectivorous bats". Acta Chiropterologica. 9: 261–267. doi:10.3161/1733-5329(2007)9[261:cogpbf]2.0.co;2.

- ↑ Szpak, Paul; Millaire, Jean-Francois; White, Christine D.; Longstaffe, Fred J. (2012). "Influence of seabird guano and camelid dung fertilization on the nitrogen isotopic composition of field-grown maize (Zea mays)". Journal of Archaeological Science. 39 (12): 3721–3740. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2012.06.035.

- 1 2 Hutchinson, G. Evelyn (1950). "Survey of Existing Knowledge of Biogeochemistry: 3. The Biogeochemistry of Vertebrate Excretion". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 96: 1–554.

- ↑ Skaggs, Jimmy (1994). The Great Guano Rush: Entrepreneurs and American Overseas Expansion. New York: St. Martin's. ISBN 0312103166.

- ↑ Méndez, Cecilia (1987). Los trabajadores guaneros del Perú, 1840–1879. Lima: Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos.

- ↑ Larson, Brooke (2004). Trials of Nation Making: Liberalism, Race, and Ethnicity in the Andes, 1810-1910. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 146. ISBN 978-0521567305.

- ↑ Crow, The Epic of Latin America, p. 180

- ↑ McKelvey VE (1967). "A summary of the salient features of the geology of phosphate deposits, their origin, and distribution" (PDF). Geological Survey Bulletin. 1252-D. D14.

- ↑ Bernat M, Loubet M, Baumer A (1991). "Sur l'origine des phosphates de l'atoll corallien de Nauru" [On the origin of phosphates from the Nauru atoll] (PDF). Oceanologica Acta (in French). 14 (4).

- ↑ Glenn, Craig, et al., eds. (2000). Marine Authigenesis: From Global to Microbial. Tulsa, OK.

- ↑ Wolfe, David W. (2001). Tales from the underground a natural history of subterranean life. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Perseus Pub. ISBN 0-7382-0128-6. OCLC 46984480.

- ↑ Dwyer, Jim (10 June 2001). "June 3–9; The Root of a Famine". The New York Times. p. 2.

- ↑ Gómez-Alpizar, Luis; et al. (2007). "An Andean origin of Phytophthora infestans inferred from mitochondrial and nuclear gene genealogies". PNAS. 104: 3306–11. doi:10.1073/pnas.0611479104. PMC 1805513. PMID 17360643.

- ↑ Nie, Yaguang; Liu, Xiaodong; Wen, Tao; Sun, Liguang; Emslie, Steven D. (2014). "Environmental implication of nitrogen isotopic composition in ornithogenic sediments from the Ross Sea region, East Antarctica: Δ15N as a new proxy for avian influence". Chemical Geology. 363: 91–100. doi:10.1016/j.chemgeo.2013.10.031.

- ↑ "h2g2 - Seabird Guano and Bat Dung". Bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 2013-01-26.

- ↑ Note: A scan of the Loreley sheet music and lyrics (printed in 1859; note the spelling "Lorelei") are available on the commons in three images: File:Lorelei1.gif, File:Lorelei2.gif, File:Lorelei3.gif

- ↑ Charles Godfrey Leland, Gaudeamus! Humorous Poems by Joseph Viktor von Scheffel, Ebook-Nr. 35848 on gutenberg.org

- ↑ Guano and the Opening of the Pacific World: A Global Ecological History, Gregory T. CushmanCambridge University Press, 25.03.2013, p. 51

Further reading

- Cushman, Gregory T. (2013). Guano and the opening of the Pacific world: a global ecological history. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107314030. Retrieved 2013-06-13.

- Hague, James D. (1862). On the phosphatic guano islands of the Pacific Ocean. Retrieved 2013-06-13.

- Skaggs, Jimmy M. (1994). The great guano rush: entrepreneurs and American overseas expansion. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0312103166.

- Robinson, Solon (1853). Guano: a treatise of practical information for farmers. New York: Solon Robinson.

- Pacific Guano Company (1876). The Pacific Guano Company; its history; its products and trade; its relation to agriculture. Exhausted guano islands of the Pacific Ocean; Howland's island, Chiacha Islands, etc., etc. The Swan Islands. The marl beds and phosphate rock of South Carolina. Chisolm's Island phosphate. The menhaden. Cambridge: Printed for the Pacific Guano Company at the Riverside Press.

- Teschemacher, James E. (1845). Essay on guano; describing its properties and the best methods of its application in agriculture and horticulture; with the value of importations from different localities; founded on actual analyses, and on personal experiments upon numerous kinds of trees, vegetables, flowers, and insects, in this climate. Boston: A.D. Phelps.

Africa

- Eden, Thomas Edward (1846). The search for nitre, and the true nature of guano: being an account of a voyage to the south-west coast of Africa: also a description of the minerals found there, and of the guano islands in that part of the world. London: R. Groombridge. Retrieved 2013-06-13.

- Morrell, Benjamin (1832). A Narrative of Four Voyages...etc. New York: J & J Harper. Retrieved December 17, 2009.

- Teale, E.O. (1934). The Limestone caves and hot springs of the Songwe river (Mbeya) area with the notes associated Guano deposits. XII. The East Africa Natural History Society.

Chile

- Pissis, Aimé (1878). Nitrate and Guano Deposits in the Desert of Atacama: An Account of the Measures Taken by the Government of Chile to Facilitate the Development Thereof. London: Taylor and Francis.

Peru

- Duffield, Alexander James (1877). Peru in the guano age: being a short account of a recent visit to the guano deposits, with some reflections on the money that they have produced and the uses to which it has been applied. London: Richard Bentley and Son.

- Duffield, Alexander James (1881). The Prospects of Peru: The End of the Guano Age and a Description Thereof. With Some Account of the Guano Deposits and Nitrate Plains. London: Newman & Co.

- Hollett, Davi (2008). More Precious than Gold: The Story of the Peruvian Guano Trade. Fairleigh Dickinson. ISBN 1611473578.

- Nesbit, John Colis (1856). On agricultural chemistry, and the nature and properties of Peruvian guano. London: Longman and Co.

Documents

- "Prospectus of the American Guano Company". 1855. Retrieved 2013-06-13.

- Coker, Robert Ervin (1910). The fisheries and the guano industry of Peru. Washington DC: Government Printing Office. Retrieved 2013-06-13.

- "Report of the Inspector of Guano : Maryland". 1849. Retrieved 2013-06-13.

- United States Department of Agriculture, Office of Experiments (1918). Bat guanos of Porto Rico and their fertilizing value. Mayagüez, P.R.: Porto Rico Agricultural Experiment Station.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Guano. |

![]()