To a Skylark

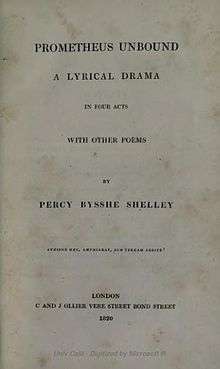

"To a Skylark" is a poem completed by Percy Bysshe Shelley in late June 1820 and published accompanying his lyrical drama Prometheus Unbound by Charles and James Collier in London.[1]

It was inspired by an evening walk in the country near Livorno, Italy, with his wife Mary Shelley, and describes the appearance and song of a skylark they come upon.[2] Mary Shelley described the event that inspired Shelley to write "To a Skylark": "In the Spring we spent a week or two near Leghorn (Livorno) ... It was on a beautiful summer evening while wandering among the lanes whose myrtle hedges were the bowers of the fire-flies, that we heard the carolling of the skylark."

Alexander Mackie argued in 1906 that the poem, along with John Keats' "Ode to a Nightingale", "are two of the glories of English literature": "The nightingale and the lark for long monopolised poetic idolatry--a privilege they enjoyed solely on account of their pre-eminence as song birds. Keats's Ode to a Nightingale and Shelley's Ode to a Skylark are two of the glories of English literature; but both were written by men who had no claim to special or exact knowledge of ornithology as such."[3]

Structure

The poem consists of twenty-one stanzas made up of five lines each. The first four lines are metered in trochaic trimeter, the fifth in iambic hexameter, also called Alexandrine. The rhyme scheme of each stanza is ABABB.

Summary

The poem begins with a description of the skylark high above in the sky. The bird is characterized as a “Spirit”. Its song is described as “unpremeditated art”. The skylark is able to sing while it ascends overhead. Its flight is compared to a “cloud of fire”. It soars across the descending sun like an “unbodied joy”. It flies in the purple evening like “a star of Heaven”. It cannot be seen but its song can be distinctly heard.

The skylark's song is compared to other natural phenomena by a series of similes. The song is compared to moonbeams which spread out from behind a cloud during the silence of the night. The song of the skylark is compared to rain drops from “rainbow clouds”, but these cannot match it.

The skylark is then compared to a poet. This is its underlying theme. How can a poet match the song of the skylark? It is symbolic of the poet and what the poet represents and strives for and ultimately achieves. The song of the bird is compared to “hymns” which poets sing. The song of the bird and the hymn of the poet are “unbidden” but arouse “sympathy” because they strike a chord that evokes the “fears and hopes” of mankind. Both resonate.

The bird's song is compared to a “high-born maiden” in a tower of a palace who likewise uses music to experience and exude love.

The skylark is compared to a golden glow-worm which moves “unbeholden” through flowers and grass.

It is compared to a rose whose petals are blown away by wind gusts which release its unmistakable scent.

It is compared to rain showers which revive the grass and the flowers. These are “joyous”, “clear”, and “fresh”. But the music of the skylark surpasses them all.

The bird is compared to a “Sprite” returning to its characterization as a spirit. The author seeks to learn what its song can teach us. What are its “thoughts”? It surpasses love and wine. Its “rapture” is “divine”. Even a hymn to marriage or to victory pales by comparison. They are flawed. But the song of the skylark is flawless, perfect.

Who is this song directed to? What is its source? The mountains, waves, fields, the shapes of the sky or plain? Love “of thine own kind” or “ignorance of pain”? The “keen joyance” of the skylark is unburdened with languor or annoyance. The skylark sings of a love that does not show “love’s sad satiety”. It is an unquenchable love.

The skylark is not troubled by death as mankind is. Its understanding of death is “clear and deep”. Its song flows in a “crystal stream”.

As Shelley wrote in "Mutability", mankind cannot achieve perfect happiness or bliss as human emotions and thoughts are never unalloyed with pain, sorrow, and loss:

We look before and after,

And pine for what is not:

Our sincerest laughter

With some pain is fraught;

Our sweetest songs are those that tell of saddest thought.

Man, by contrast to the skylark, cannot achieve this perfect equanimity, serenity, or solace. Mankind is troubled by thought of the past and future. Man fears death. Man “pines for what is not”, for phantoms and illusions. Purity cannot be achieved. Laughter is always mingled with pain. Human songs, in contrast to that of the skylark, are mixed with sadness, are those that “tell of saddest thought”.

Mankind is imbued with “hate”, “pride”, and “fear”. Even without these limitations, even if we could avoid all pain, we still could not equal the song of the skylark.

The "skill" of the bird’s song exceeds all other sounds and even “treasures” to be found in books. This is because the skylark’s song is unearthly, but spiritual and ethereal.

The author seeks to learn from the skylark’s song the secret of “gladness”, of happiness. If the author can learn even half of what causes that joy, that “harmonious madness”, then mankind would listen to the author’s poem as he does to the skylark’s song.

The skylark’s song is a metaphor or symbol of Nature.[4] As in “The Cloud”, Shelley seeks to understand nature, to find its meaning. This is his objective. The poem is infused with pathos because he knows that this is an illusive quest.

E. Wayne Marjarum argued that the theme was "an ideal being transcending common experience".[5] Irving T. Richards maintained that the poem represented "the ideal being's full isolation from mundanity" in which "rhetorical questions concerning the source of his ideal's inspiration" are addressed.[6]

Influence

Thomas Hardy wrote the poem "Shelley's Skylark" which referenced the work in 1887 after a trip to Leghorn or Livorno, Italy: "The dust of the lark that Shelley heard."[7]

The 1941 comic play Blithe Spirit by Noël Coward takes its title from the opening line: "Hail to thee, blithe Spirit! / Bird thou never wert".

In 1894, music by British composer Arthur Goring Thomas was set to verses from the work in the composition The Swan and the Skylark: Cantata orchestrated by Sir Charles Villiers Stanford.[8]

The poem was quoted in the 1979 musical Shelley which was written and directed by Moma Murphy with music composed by Ralph Martell.[9]

In 2004, Mark Hierholzer set the lyrics to music in a score for chorus with keyboard accompaniment entitled "Ode to a Skylark".[10]

In 2006, American composer Kevin Mixon wrote a score for band with an eponymous title based on the poem. Mixon explained: "I wanted to capture the exuberance in Shelley's To a Skylark."[11]

References

- ↑ Sandy, Mark (21 March 2002). "To a Skylark". The Literary Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2006-01-09.

- ↑ Sandy 2002. Retrieved 2006-01-09.

- ↑ Mackie, Alexander (1906), Nature Knowledge in Modern Poetry. New York: Longmans-Green & Company, OCLC 494286564. p. 29.

- ↑ Marjarum, E. Wayne. "The Symbolism of Shelley's 'To a Skylark'." Modern Language Association, Vol. 52, No. 3 (Sep., 1937), pp. 911-913.

- ↑ Marjarum 1937 p. 911.

- ↑ Richards, Irving T. "A Note on Source Influences in Shelley's Cloud and Skylark," PMLA, Vol. 50, No. 2 (June, 1935), pp. 562-567.

- ↑ "'Shelley's Skylark', a poem by Thomas Hardy." British Library.

- ↑ The Swan and the Skylark: Cantata by Arthur Goring Thomas, Felicia Dorothea Browne Hemans, John Keats, Percy Bysshe Shelley, Sir Charles Villiers Stanford.

- ↑ Shepard, Richard F. "It's Lyrics by P.B. Shelley", 15 April, 1979. The New York Times. Shelley musical.

- ↑ 2004 Ode to a Skylark score.

- ↑ 2006 To a Skylark score.

Sources

- Behrendt, Stephen C. Shelley and His Audiences. University of Nebraska Press: Lincoln and London, 1989.

- Burt, Mary Elizabrth, ed. Poems That Every Child Should Know. BiblioBazaar, 2009. First published in 1904 in New York by Doubleday, Page & Company.

- Cervo, Nathan. "Hopkins' 'The Caged Skylark' and Shelley's 'To a Skylark.'" Explicator, 47.1(1988): 16–20.

- Costa, Fernanda Pintassilgo da. "Shelley e Keats: 'To a Skylark', 'Ode on a Nightingale'." Unpublished BA thesis, Universidade de Coirnbra. Bibliography (1944): 333.

- Doggett, Frank. "Romanticism's Singing Bird." Studies in English Literature, 1500-1900, Vol. 14, No. 4, Nineteenth Century (Autumn, 1974), pp. 547-561.

- Ford, Newell F. "Shelley's 'To a Skylark'." Keats-Shelley Memorial Bulletin, XI, 1960, pp. 6-12.

- Holbrook, Morris B. "Presidential Address: The Role of Lyricism in Research on Consumer Emotions: Skylark, Have You Anything to Say to Me?" in NA - Advances in Consumer Research, Volume 17, eds. Marvin E. Goldberg, Gerald Gorn, and Richard W. Pollay, Provo, UT: Association for Consumer Research, Pp. 1-18.

- Hunter, Parks, C., Jr. "Undercurrents of Anacreontics in Shelley's 'To a Skylark' and 'The Cloud'. Studies in Philology, Vol. 65, No. 4 (Jul. 1968), pp. 677–692.

- Lewitt, Philip Jay. "Hidden Voices: Bird-Watching in Shelley, Keats, and Whitman." Kyushu American Literature, 28 (1987): 55–63.

- MacEachen, Dougald B. CliffsNotes on Shelley's Poems. 18 July 2011. "Literature Notes - Homework Help - Study Guides - Test Prep - CliffsNotes". Archived from the original on 5 March 2013. Retrieved 23 September 2014.

- Mackie, Alexander. Nature Knowledge in Modern Poetry. New York: Longmans-Green & Company, 1906. OCLC 494286564.

- Mahoney, John L. "Teaching 'To a Sky-Lark' in Relation to Shelley's Defense." Hall, Spencer (ed.). Approaches to Teaching Shelley's Poetry. New York: MLA, 1990. 83–85.

- McClelland, Fleming. "Shelley's 'To a Sky-Lark.'" Explicator, 47.1 (1988): 15–16.

- Meihuizen, N. "Birds and Bird-Song in Wordsworth, Shelley and Yeats: The Study of a Relationship between Three Poems." English Studies in Africa, 31.1 (1988): 51–63.

- Norman, Sylvia. Flight of the Skylark: The Development of Shelley's Reputation. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1954.

- O'Neil, Michael. Percy Bysshe Shelley: A Literary Life. The MacMillan Press, Ltd.: London, 1989.

- Richards, Irving T. "A Note on Source Influences in Shelley's Cloud and Skylark," PMLA, Vol. 50, No. 2 (June, 1935), pp. 562-567.

- Runcie, Catherine. (1986) "On Figurative Language: A Reading of Shelley’s, Hardy’s and Hughes’s Skylark Poems," Journal of the Australasian Universities Language and Literature Association, 66:1, 205-217.

- Shawa, W. A. (2015). Styistic Analysis of the Poem 'To A Skylark' by P.B. Shelley." Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 20(3), 124-137.

- SparkNotes Editors. “SparkNote on Shelley’s Poetry.” SparkNotes.com. SparkNotes LLC. 2002. Web. 11 Jul 2011.

- Stevenson, Lionel. "The 'High-Born Maiden' Symbol in Tennyson." PMLA, Vol. 63, No. 1 (Mar., 1948), pp. 234-243.

- Tillman-Hill, Iris. "Hardy's Skylark and Shelley's," VP, 10 (1972), 79-83.

- Tomalin, Claire. Shelley and His World. Thames and Hudson, Ltd.: London, 1980.

- Ulmer, William A. "Some Hidden Want: Aspiration in 'To a Sky-Lark.'" Studies in Romanticism, 23.2 (1984): 245–58.

- White, Ivey Newman. Portrait of Shelley. Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.: New York, 1945.

- Wilcox, Stewart C. "The Sources, Symbolism, and Unity of Shelley's 'Skylark'." Studies in Philology, Vol. 46, No. 4 (Oct., 1949), pp. 560-576.

- Zillman, Lawrence John. Shelley's Prometheus Unbound. University of Washington Press: Seattle, 1959.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Audiorecording of "To a Skylark" read by Kara Shallenberg on LibriVox, track 64, from Poems Every Child Should Know (1904), Mary E. Burt, ed.

- 608. To a Skylark. Online version on Bartleby.com.

- Shelley's Skylark: A Facsimile of the Original Manuscript. Cambridge, MA: Library of Harvard University, 1888.

- An introduction to ‘To a Skylark’. British Library.