Greyhound racing

Greyhound racing is an organized, competitive sport in which greyhound dogs are raced around a track. There are two forms of greyhound racing, track racing (normally around an oval track) and coursing.[1] Track racing uses an artificial lure (now based on a windsock)[2] that travels ahead of the dogs on a rail until the greyhounds cross the finish line. As with horse racing, greyhound races often allow the public to bet on the outcome. In coursing, the dogs chase a stuffed lure (originally a live hare or rabbit that could be killed by the dog, but this has long since been banned in the U.S.).[3]

In many countries greyhound racing is purely amateur and solely for enjoyment. In other countries, particularly Australia, Ireland, Macau, Mexico, Spain, the UK and the US, greyhound racing is part of the gambling industry and similar to horse racing – although far less profitable. Animal rights and animal welfare groups[4] are critical of the welfare of dogs in the commercial racing industry.

A greyhound adoption movement spearheaded by kennel owners has arisen to assist retired racing dogs in finding homes as pets, with an estimated adoption rate of over 95% in the US.[5]

History

Modern greyhound racing has its origins in coursing.[6] The first recorded attempt at racing greyhounds on a straight track was made beside the Welsh Harp reservoir, Hendon, England, in 1876, but this experiment did not develop. The industry emerged in its recognizable modern form, featuring circular or oval tracks, with the invention of the mechanical or artificial hare, in 1912, by an American, Owen Patrick Smith. O.P. Smith had altruistic aims for the industry to stop the killing of the jack rabbits and see "greyhound racing as we see horse racing". In 1919, Smith opened the first professional dog-racing track with stands in Emeryville, California.[7] The certificates system led the way to parimutuel betting, as quarry and on-course gambling, in the United States during the 1930s.

The oval track and mechanical hare were introduced to Britain, in 1926, by another American, Charles Munn, in association with Major Lyne-Dixson, a Canadian, who was a key figure in coursing. Finding other supporters proved rather difficult however and with the General Strike of 1926 looming, the two men scoured the country in an attempt to find others who would join them. Eventually they met Brigadier-General Critchley, who introduced them to Sir William Gentle.[1] Between them they raised £22,000 and like the American 'International Greyhound Racing Association' (or the I.G.R.A.), they launched the Greyhound Racing Association[8] holding the first British meeting at Manchester's Belle Vue Stadium. The industry was successful in cities and towns throughout the UK – by the end of 1927, there were forty tracks operating.

The industry of greyhound racing was particularly attractive to predominantly male working-class audiences, for whom the urban locations of the tracks and the evening times of the meetings were accessible, and to patrons and owners from various social backgrounds. Betting has always been a key ingredient of greyhound racing, both through on-course bookmakers and the totalisator, first introduced in 1930. Like horse racing, it is popular to bet on the greyhound races as a form of parimutuel gambling.

Greyhound racing enjoyed its highest UK attendances just after the Second World War — for example, attendances during 1946 were estimated to be around 75 million based on an annual totalisator turnover of £196,431,430.[9] [10] The industry experienced a decline from the early 1960s after the 1960 UK Betting and Gaming Act permitted off-course cash betting. Sponsorship, limited television coverage, and the later abolition of on-course betting tax have partially offset this decline.

Today

Commercial greyhound racing is characterized by several criteria, including legalized gambling, the existence of a regulatory structure, the physical presence of racetracks, whether the host state or subdivision shares in any gambling proceeds, fees charged by host locations, the use of professional racing kennels, the number of dogs participating in races, the existence of an official racing code, and membership in a greyhound racing federation or trade association.

In addition to the eight countries where commercial greyhound racing exists, in at least twenty-one countries dog racing occurs, but has not yet reached a commercial stage.

In 2016, a bill was passed through the government of the state New South Wales, in Australia to ban greyhound racing. This new law was to come into effect in the middle of 2017 but was reversed in late 2016, albeit with several new restrictions on the industry (see below under Australia).

Medical care

The medical care of a racing greyhound is primarily the responsibility of the trainer while in training. All tracks in the United Kingdom have to have a veterinary surgeon on site during racing.[11] Greyhound adoption groups frequently report that the dogs from the tracks have tooth problems, the cause of which is debated. The groups often also find that the dogs carry tick-borne diseases and parasites due to the lack of proper preventative treatments. The dogs require annual vaccination against Distemper, Infectious canine hepatitis, Parvovirus, Leptospirosis and a regular vaccination to minimize outbreaks of diseases such as kennel cough.[12]

Doping cases have been reported in greyhound racing. The racing industry is actively working to prevent the spread of this practice; attempts are being made to recover urine samples from all greyhounds in a race, not just the winners. Greyhounds from which samples cannot be obtained for a certain number of consecutive races are subject to being ruled off the track. Violators are subject to criminal penalties and loss of their racing licenses by state gaming commissions and a permanent ban from the National Greyhound Association. The trainer of the greyhound is at all times the "absolute insurer" of the condition of the animal. The trainer is responsible for any positive test regardless of how the banned substance has entered the greyhound's system.[12] However, annual reports from 2007 to 2017 published by the Florida Department of Business and Professional Regulation Pari-mutuel Wagering Division, where the majority of U.S. tracks are located, report that there is only a 0.015% yield of a positive drug test result for any banned substances, despite what any groups who oppose racing may claim.[13]

Retirement

Generally, a greyhound's career will end between the ages of four and six – after the dog can no longer race, or possibly when it is no longer competitive. The best dogs are kept for breeding and there are industry-associated adoption groups and rescue groups that work to obtain retired racing greyhounds and place them as pets. In the United Kingdom, the Greyhound Board of Great Britain (GBGB) have introduced measures to locate where racing greyhounds reside after they have retired from racing and as from 2017 has been available to the public.[14] There have been isolated cases of controversy, such as greyhounds sold to research labs [15] [16][17] and healthy greyhounds being destroyed with a captive bolt gun.[18] In both cases the guilty parties were found and legal action ensued.[19] [20]

Several organizations, such as British Greyhounds Retired Database, Greyhound Rescue West of England, Birmingham Greyhound Protection, GAGAH, Adopt-a-Greyhound and Greyhound Pets of America, and the Retired Greyhound Trust try to ensure that as many of the dogs as possible are adopted. Some of these groups also advocate better treatment of the dogs while at the track and/or the end of racing for profit. In recent years the racing industry has made significant progress in establishing programs for the adoption of retired racers.[11] In addition to actively cooperating with private adoption groups throughout the country, many race tracks have established their own adoption programs at various tracks.[11]

Criticism

Greyhound racing has been a source of controversy since the 1980s. A number of animal welfare organizations are critical of the greyhound racing industry, alleging that industry standard practices are cruel and inhumane, and that the industry violates animal welfare laws and conceals evidence of wrongdoing.

There has also been criticism of commercial racing internationally, particularly regarding the overbreeding of dogs, concealment of injury figures and high euthanasia rates. An independent 2014 review of the Irish Greyhound Board criticized the body's corporate governance, its handling of animal welfare issues, and poor financial performance.[21]

In the U.S., the humane community has successfully lobbied an increasing number of state legislatures to improve conditions for racing greyhounds or to ban the sport altogether. In 2014, Colorado became the 39th state to prohibit greyhound racing.[22]

In Australia, Greyhound Racing New South Wales (GRNSW) Chief Executive Brent Hogan said in 2013 that an estimated 3,000 greyhounds are euthanized each year in that state alone.[23]

In February 2015, a report by television program Four Corners discovered the use of 'live bait' to train dogs for racing in Australia.[24] This is illegal in many countries, including the UK and Australia, and against the rules and regulations of the UK Animal Welfare Act 2006.[25][26]

Australian former High Court judge Michael McHugh conducted a Special Commission of Inquiry for the Australian state of New South Wales.[27] The review evaluated the breeding and wastage practices, the use of coursing and live baiting by some trainers, and the reporting rate of deaths of dogs at race tracks. The review concluded that there was widespread cover-ups and deception of the public. Other key findings in the report included: a high death rate, where at least 48,891 uncompetitive greyhounds were killed over the past twelve years, and the under reporting of greyhound deaths and injuries despite a recent undercover exposé. The report also found up to twenty percent of trainers engaged in illegal live baiting practices, and that for the industry to remain viable, 2,000 to 4,000 greyhounds would still be killed each year.[28] New South Wales premier Mike Baird announced that all greyhound racing would be banned in the state from 1 July 2017.[29]

By country

Argentina

On 17 November 2016, the Congress banned greyhound racing.[30] The law was promulgated on 2 December 2016 as the National Law 27,330. Anyone who organizes, promotes, facilitates or carries out a dog race, regardless of breed, will be jailed for between 3 months and 4 years, with a fine of from $4,000 to $80,000 pesos.[31]

Australia

Greyhounds Australasia consists of governing bodies in all states and New Zealand, which regulate greyhound welfare and living conditions. Most racing authorities in Australia have organized and funded Greyhound Adoption arms, which house dozens of greyhounds a month, as well as partly supporting private volunteer organisations.

Each Australian state and territory has a governing greyhound racing body. Greyhound Racing New South Wales (GRNSW) and Greyhound Racing Victoria (GRV) are the two largest authorities, governing over 40 racetracks. The Queensland Greyhound Racing Authority (QGRA), Western Australian Greyhound Racing Authority (WAGRA), Tasmanian Greyhound Racing Authority (TGRA), Greyhound Racing South Australia (GRSA), Northern Territory Racing Authority, and the Canberra Greyhound Racing Club (CGRC), all contribute to running and monitoring of greyhound racing in Australia.

Major greyhound racing venues include Wentworth Park in Sydney, Cannington Raceway in Perth, Greyhound Park in Adelaide, Albion Park in Brisbane and Sandown Greyhounds in Melbourne.[32]

Many adoption programs have been set up throughout Australia known as Greyhound Adoption Program or Greyhounds As Pets, GAP. Greyhounds are checked for parasites, malnourishment, or any other medical conditions by an on-course vet before being able to compete. Greyhounds are usually bought and sold as puppies just after having been whelped or as racing dogs that have been fully trained via word of mouth on the track or via the few greyhound trading and sales platforms. In Australia the buying and selling of greyhounds is subject to oversight by the states and territories.

A 2015 television investigation revealed widespread use of small live animals as bait, to train greyhounds to chase and kill.[33] As a result, many in the industry called for a complete overhaul of greyhound racing's controlling bodies in Australia.[34]

Ireland

Greyhound racing is a popular industry in Ireland with the majority of tracks falling under the control of the Irish Greyhound Board (IGB) which is a commercial semi-state body and reports to the Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine.[35] The vast majority of greyhounds racing in the UK are imported from Irish breeders (estimated 90%). In the greyhound industry Northern Irish tracks are considered to be in the category of Irish greyhound racing and the results are published by the IGB. They do not come under the control of the Greyhound Board of Great Britain.

New Zealand

In New Zealand, around 700 dogs are bred each year for racing,[36] and around 200–300 are imported from Australia.[37] Over 200 are retired annually by a charity established and partially funded by the New Zealand Greyhound Racing Association.[38] Few greyhounds are kept as pets or rehomed by their trainers after racing [39] while a small percentage are rehomed by other volunteer greyhound rescue organizations throughout the country. Very occasionally greyhounds are even returned to overseas owners. There is some concern over the welfare of New Zealand racing greyhounds by a growing animal advocacy lobby[40] that led the Greyhound Racing Association to initiate an internal inquiry into post-career outcomes in 2013.[41] In 2017 a second report was commissioned, this time by the New Zealand Racing Board, led by former High Court Judge Rodney Hansen, that found little change for greyhounds and few reforms implemented.[42] On Dec 20 2017, the New Zealand government's Minister for Racing Hon Winston Peters, said the reports findings were "disturbing and deeply disappointing",[43] and "simply unacceptable".[44]

South Africa

In South Africa dogs are kept with their owners. Due to the amateur state of racing, owners are usually also the trainer and rearer of the dogs; it is very rare that a dog is kenneled with a trainer.

Racing is controlled by a partnership between the United Greyhound Racing and Breeders Society (UGRABS) and the South African Renhond Unie (SARU – South African Racing Dog Union). The studbook is kept by the South African Studbook Organization, who keep studbooks for all stud animals. Racing takes place on both oval and straight tracks. Racing is illegal in South Africa.

United Kingdom

Greyhound racing is a popular industry in Great Britain with attendances at around 3.2 million at over 5,750 meetings in 2007. There are currently 21 registered stadiums in Britain, and a parimutuel betting tote system with on-course and off-course betting available.[45]

On 24 July 1926, in front of 1,700 spectators, the first greyhound race took place at Belle Vue Stadium where seven greyhounds raced around an oval circuit to catch an electric artificial hare.[46] This marked the first modern greyhound race in Great Britain.

Greyhound racing in Great Britain is regulated by the Greyhound Board of Great Britain (GBGB). Greyhounds are not kept at the tracks, and are instead housed in the kennels of trainers and transported to the tracks to race. Those who race on the independent circuit (known as 'flapping'), do not have this regulation.[47] There have been 143 regulated tracks (126 in England, 12 in Scotland and 5 in Wales) and 256 known independent tracks since 1926.[8]

Some of the more prominent stadiums that have closed where greyhound racing has been staged in the past are as follows: White City Greyhounds at White City Stadium, Walthamstow Stadium, Wimbledon Stadium, Wembley Greyhounds at Wembley Stadium, Harringay Stadium, West Ham Stadium, Powderhall Stadium and Cardiff Arms Park.

Greyhound racing as a whole in the UK peaked in 1946 but has been in decline since the opening of betting shops in 1961 and despite a mini boom in the late 1980s there are only 21 licensed tracks left in Britain.[48]

United States

In the United States, greyhound racing is governed by state law. Industry attempts at self-regulation have been criticized by humane organizations.[49] There are strict industry imposed enforcement system, in conjunction with state and local laws.[50]

At American tracks, greyhounds are kept in kennel compounds, in crates that are approximately three feet wide, four feet deep, and three feet high.[51] Most kennels turn the dogs out 4 to 6 times per day. Each turnout can be from 30 to 90 minutes.[52] Because greyhound kennels often house upwards of 50–70 dogs, crating is essential to the safety and wellbeing of canine life.[53] Greyhounds are cared for by professional and licensed staff.

In addition to state law and regulations, most tracks adopt their own rules, policies and procedures. In exchange for the right to race their greyhounds at the track, kennel owners must sign contracts in which they agree to abide by all track rules, including those pertaining to animal welfare. If kennel owners violate these contract clauses, they stand to lose their track privileges and even their racing licenses. In order to be licensed to own, handle a race dog or work in a kennel, dog professionals must have a FBI background check and be licensed by the states. Additionally, the National Greyhound Association holds their membership to strict standards towards the care and handling of the dogs. Failure to comply can result in lifetime termination of membership and a ban from the sport.

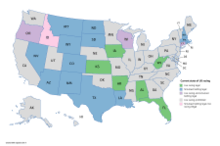

In recent years, several state governments in the United States have passed legislation to improve the treatment of racing dogs in their jurisdiction. During the 1990s, seven states banned gambling on live greyhound racing. In November 2008, Massachusetts held a vote to ban greyhound racing, which passed 56% to 44%. Currently, 40 states and the territory of Guam have standing laws banning the practice, and 4 more states, Connecticut, Kansas, Oregon and Wisconsin, do not practise greyhound racing despite the practice not being illegal there.[54]

Texas, Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, and West Virginia have active racing industries. Fifteen states without live racing allow simulcast betting on greyhound races in other states.[55][56]

Between 2001 and 2011, the total amount gambled on greyhound racing nationwide declined by 67%.[57]

In Florida, where 11 of the operational dog tracks in the US remain, the financial decline is even more significant. In the state, the amount gambled at dog tracks declined by 72% between 1990 and 2013.[58] According to a study commissioned by the legislature, the state lost between $1 million and $3.3 million on greyhound racing in 2012.[59] As recently as 2016, Florida industry professionals are starting to question if wagering is seeing a decline or just transitioning to unreported online formats. [60]

On November 6, 2018, Florida residents will vote on Amendment 13, which if passed would phase out commercial dog racing in Florida by 2020.[61] Supporters of the amendment report that greyhounds used in racing spend the majority of their time locked inside cramped cages, when not racing. Dogs are also frequently drugged, injured, die of exposure,[62] exhaustion or injuries,[63] and many more are killed when retired.[64] In 2017, an investigation by the animal protection organization PETA exposed The Pet Blood Bank in Cherokee, Texas, where 150 greyhounds formerly used in racing were living in filth and squalor.[65] [66] The animals were used as blood "donors", and were being kept in solitary confinement with no exercise or companionship, and many had open wounds and were emaciated. Public outcry led to the dogs being surrendered to adoption programs, and the National Greyhound Association barred members from directly sending greyhounds to blood banks.[67]

List of United States active tracks

- Birmingham Race Course, Birmingham, Alabama

- Southland Park Gaming and Racing, West Memphis, Arkansas

- Daytona Beach Racing and Card Club (renamed), Daytona Beach, Florida

- Derby Lane Greyhound Track, St. Petersburg, Florida

- Ebro Greyhound Park and Poker Room, Ebro, Florida

- Big Easy Casino, Hallandale Beach, Florida

- Melbourne Greyhound Park & Club 52 Poker, Melbourne, Florida

- Naples-Fort Myers Track and Entertainment Center, Bonita Springs, Florida

- Orange Park Kennel Club, Orange Park, Florida

- Palm Beach Kennel Club, West Palm Beach, Florida

- Pensacola Greyhound Track, Pensacola, Florida

- Sanford-Orlando Kennel Club, Longwood, Florida

- Sarasota Kennel Club, Sarasota, Florida

- Gulf Greyhound, La Marque, Texas

- Tri State Greyhound Track, Nitro, West Virginia

- Wheeling Island Hotel-Casino-Racetrack, Wheeling, West Virginia

- Iowa Greyhound Park, Dubuque, Iowa

See also

References

- 1 2 Genders, Roy (1981). the Encyclopaedia of Greyhound Racing. Pelham Books Ltd. ISBN 0-7207-1106-1.

- ↑ "American Greyhound Council – Frequently Asked Questions About Greyhound Pets". agcouncil.com. Retrieved 8 August 2016.

- ↑ "Shocking New Audio Of Cruel "Live Lure" Greyhound Training – Care2 Causes". care2.com. Retrieved 8 August 2016.

- ↑ "What are the animal welfare issues associated with greyhound racing in Australia? - RSPCA Australia knowledgebase". kb.rspca.org.au.

- ↑ "American Greyhound Council – Adoption Programs". agcouncil.com. Retrieved 8 August 2016.

- ↑ "dog racing." Encyclopædia Britannica, Online Library Edition, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 2012. Web. 5 Feb. 2012

- ↑ Jane Alexiadis, What's it Worth? Greyhound collection sale to benefit charity, San Jose Mercury News (23 December 2011).

- 1 2 "Greyhound Racing History". greyhoundracinghistory.co.uk. Archived from the original on 13 April 2015. Retrieved 9 April 2015.

- ↑ Particulars of Licensed tracks, table 1 Licensed Dog Racecourses. Licensing Authorities. 1946.

- ↑ ""Stock Exchange." Times, 17 Apr. 1947, p. 9". The Times Digital Archive.

- 1 2 3 "Welfare". Greyhound Board of Great Britain.

- 1 2 "Answers to Commonly Asked Questions". Greyhound Protection League Official. Retrieved 19 November 2012.

- ↑ "77th-86th Annual Reports 2007-2017". Pari-Mutuel Wagering Division, FLDBPR. Retrieved 15 September 2018.

- ↑ "Welfare & Retirement". Greyhound Board of Great Britain.

- ↑ Qureshi, Yakub (28 April 2010). "¿30 injured greyhounds put down at dog track". menmedia.co.uk. Retrieved 8 August 2016.

- ↑ Foggo, Daniel (11 May 2008). "Greyhound breeder offers slow dogs to be killed for research". The Times. London.

- ↑ Jeory, Ted (29 May 2010). "Agony of caged greyhounds". express.co.uk. Retrieved 8 August 2016.

- ↑ Foggo, Daniel (16 July 2006). "Killing field of the dog racing industry". The Times. London.

- ↑ "Greyhound killer to face tougher sentence". The Guardian. 16 February 2007.

- ↑ "Editors Chair". Greyhound Star.

- ↑ "Bord na gCon faces 'significant challenges' financially". The Irish Times. 7 July 2014.

- ↑ "Greyhound racing ban signed into law in Colorado". The Denver Post. The Associated Press. 10 March 2014.

- ↑ "About 3000 unwanted greyhound racing dogs put down each year in NSW". The Australian. 15 November 2013.

- ↑ "Greyhound racing: Piglets possums and rabbits used as live bait in secret training sessions Four Corners reveals". ABC News. 16 February 2015.

- ↑ "Animal Welfare Act 2006". www.legislation.gov.uk.

- ↑ "Animal Health and Welfare (Scotland) Act 2006". www.gov.scot. 20 October 2006.

- ↑ https://web.archive.org/web/20160707111904/http://www.greyhoundracinginquiry.justice.nsw.gov.au/Documents/Report-SCI-Greyhound-Racing-Industry-NSW-Volume-1.pdf

- ↑ "Special Commission of Inquiry into the Greyhound Racing Industry in New South Wales" (PDF). www.greyhoundracinginquiry.justice.nsw.gov.au.

- ↑ "NSW bans greyhound racing after evidence of systemic cruelty". abc.net.au. 7 July 2016. Retrieved 8 August 2016.

- ↑ "Se aprobó la ley que prohíbe las carreras de galgos". lanacion.com.ar.

- ↑ "BORA".

- ↑ "Australian Greyhound Racing".

- ↑ "Australian Greyhound Racing News".

- ↑ Pitstock, Kevin (18 February 2015). "Greyhound racing boards and stewards must resign". Retrieved 7 July 2016.

- ↑ "2014 Annual Report" (PDF). Irish Greyhound Board.

- ↑ "Statistics". www.galtd.org.au. Archived from the original on 2016-02-27.

- ↑ "Australian Government Non-Livestock Exps". Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- ↑ "Greyhound Adoption Programme – NZ Greyhound Racing". thedogs.co.nz. Retrieved 8 August 2016.

- ↑ "Industry funded welfare review" (PDF). thedogs.co.nz. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- ↑ "GPLNZTV". YouTube. Retrieved 2018-04-21.

- ↑ "WHK report" (PDF). grnz.co.nz. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 April 2018. Retrieved 8 August 2016.

- ↑ "NZRB report on greyhound welfare 2017" (PDF). nzrb.co.nz.

- ↑ "Farifax media: Hansen report released". stuff.co.nz. Archived from the original on 2018-04-22.

- ↑ "Winston Peters: Hansen report". www.beehive.govt.nz/.

- ↑ "Donoughue Report" (PDF). Greyhound Board of Great Britain.

- ↑ "gbgb.org.uk – GBGB". thedogs.co.uk. Retrieved 8 August 2016.

- ↑ "About GBGB". Greyhound Board of Great Britain.

- ↑ "We are the governing body for licensed greyhound racing". Greyhound Board of Great Britain.

- ↑ "GREY2K USA". grey2kusa.org. Retrieved 8 August 2016.

- ↑ "American Greyhound Council – Greyhound Care at the Track". agcouncil.com. Retrieved 8 August 2016.

- ↑ "GREY2K USA Report on Greyhound Racing in Texas (February 2013)" (PDF). grey2kusa.org. Retrieved 8 August 2016.

- ↑ "Off to the Races – Greyhound Facts". greyhoundfacts.org. Retrieved 8 August 2016.

- ↑ "National Greyhound Association: Debunking Great2K Lies about greyhound racing". www.ngagreyhounds.com.

- ↑ "Take Action: State by State". Retrieved 13 May 2015.

- ↑ "GREY2K USA: State by State". grey2kusa.org. Retrieved 8 August 2016.

- ↑ http://www.omaha.com/news/iowa/iowa-gov-branstad-signs-bill-to-end-greyhound-racing-in/article_d7180c26-8963-53a0-a7d7-b29d60791d21.html

- ↑ Association of Racing Commissioners International, Statistical Summaries for 2001 and 2011.

- ↑ "Annual Reports". Florida Department of Business and Professional Regulation, Division of Pari-Mutuel Wagering. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- ↑ "Gambling Impact Study" (PDF). Spectrum Gaming Group. Retrieved 28 October 2013.

- ↑ "Online Wager". Sunshine State News. Retrieved 22 February 2016.

- ↑ https://www.peta.org/issues/animals-in-entertainment/cruel-sports/greyhound-racing/

- ↑ Josh Brodesky, “8 Greyhounds Die on Trip: Haulers Fined, Suspended,” Arizona Daily Star 15 Dec. 2010.

- ↑ Associated Press, “20 Greyhounds Die, Euthanized in 2008 in Texas,” 26 Oct. 2009.

- ↑ Debbie Elliott, “Discovery of Thousands of Dead Greyhounds Leads to More Questions About the Dog-Racing Industry,” All Things Considered, NPR, 31 May 2002.

- ↑ "Discarded Greyhounds Imprisoned, Neglected, and Farmed for Their Blood". PETA Investigations. Retrieved 2018-09-18.

- ↑ Karin Brulliard, “Allegations of Neglect at Dog Blood Bank Shine Light on An Unregulated Industry,” The Washington Post, 23 Sep. 2017

- ↑ "National Greyhound Association: News". www.ngagreyhounds.com. Retrieved 2018-09-18.

Further reading

- Gwyneth Anne Thayer, Going to the Dogs: Greyhound Racing, Animal Activism, and American Popular Culture. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 2013.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Greyhound racing. |

- Greyhound racing at Curlie (based on DMOZ)