Golden Dragon massacre

| Golden Dragon Massacre | |

|---|---|

.jpg) 2017 photograph of Imperial Palace, which replaced the Golden Dragon in the same space | |

Golden Dragon Restaurant Golden Dragon massacre (San Francisco) | |

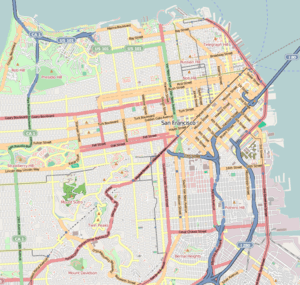

| Location | 816 Washington Street, San Francisco, California, U.S. |

| Coordinates | 37°47′42.6″N 122°24′24.8″W / 37.795167°N 122.406889°WCoordinates: 37°47′42.6″N 122°24′24.8″W / 37.795167°N 122.406889°W |

| Date |

Sunday, September 4, 1977 02:40 a.m. (PST) |

Attack type | Mass murder, massacre, gang-shooting |

| Weapons |

|

| Deaths | 5 |

Non-fatal injuries | 11 |

| Perpetrators |

Peter Ng Curtis Tam Chester Yu Melvin Yu Tom Yu |

| Motive | Rivalry between Joe Boys and Wah Ching gangs |

The Golden Dragon Massacre (traditional Chinese: 金龍酒樓大屠殺; simplified Chinese: 金龙酒楼大屠杀; pinyin: Jīnlóngjiǔlóudàtúshā; Jyutping: Gam1lung4zau2lau4daai6tou4saat3)[1] was a gang-related shooting attack that took place on September 4, 1977 inside the Golden Dragon Restaurant, located at 816 Washington Street in Chinatown, San Francisco, California. The five perpetrators, members of the Joe Boys, a Chinese youth gang, were attempting to kill members of the Wah Ching, a rival Chinatown gang. The attack left five people dead and 11 others injured, none of whom was a gang member. The perpetrators were later convicted and sentenced in connection with the murders.

Shooting

.jpg)

Motive

The incident was motivated by a longstanding feud between two rival Chinatown gangs, the Joe Boys and Wah Ching, traced back to 1969, when the first victim was killed. The two gangs controlled different parts of San Francisco, with the Wah Ching in Chinatown and the Joe Boys in the Richmond and Sunset districts, and had been rivals since the Joe Boys splintered off from the Wah Ching in the late 1960s.[2] The assassination attempt at the Golden Dragon was a direct retaliation for the shootout with the Wah Ching in Chinatown's Ping Yuen (Peace Garden) housing project (Chinese: 平園住宅房屋大廈) on 4 July 1977 which was sparked by a dispute over fireworks sales. That shootout resulted in the death of 16-year-old Felix Huey (Chinese: 許非力; sometimes romanized as Huie) and the wounding of Melvin Yu, both members of the Joe Boys.[3][4][5][6][7]

Huey's murder, in turn, was seen as a reprisal for the earlier death of Kin Chuen Louie, a 20-year-old member of the Wah Ching who had been shot a dozen times on May 31 while attempting to escape in his car.[8] The car was parked near his apartment, close to Green and Kearny.[9][10] Louie's death was later memorialized in a poem by Michael McClure, who came upon the victim shortly after the shooting.[11] Including those victims in the Golden Dragon, 44 people had been murdered during the war between the Joe Boys and Wah Ching by 1977.[12]

Preparations

The raid was planned in a Daly City apartment.[13] Preparations had begun in early 1977, when Joe Boys members began acquiring the weapons that would be used in the massacre; during the summer of 1977, Tom Yu, a leader in the Joe Boy gang, convinced a longtime friend who owned a home in Pacifica to store the weapons, wrapped in cloth, in the front closet of that home. On August 29, 1977, Yu met with Carlos Jon, a member of another gang; Yu asked Jon to keep track of Wah Ching and Hop Sing gang members over the upcoming Labor Day weekend, and showed special interest in where they might be for a late night snack.[14]

Yu gave Jon the phone number of the Pacifica home and asked him to call on the following Saturday (September 3). That Friday night (September 2, 1977), members of the Joe Boys gathered in Pacifica, retrieved the weapons and put them on display. Yu received a phone call at 1:00 a.m. on Saturday morning, and after a brief, private conversation, ordered the weapons to be put away back into the closet.[14] By this time, the group plotting the shooting consisted of Tom Yu, his brothers (Chester and Dana), Melvin Yu (no relation), Peter Ng, Peter Cheung, Curtis Tam, Kam Lee, and Don Wong.[14]

Later that evening, the gang returned to Pacifica. Around 9:30 p.m., two members of the Joe Boys, Peter Cheung and Dana Yu were asked to steal a four-door car, which would facilitate entry and exit for a quick getaway; they returned shortly afterward with a blue Dodge Dart and parked it in the home's driveway. The gang members retrieved the guns from the closet after the homeowners returned and went to sleep.[14] At 2:00 a.m., Pacific Standard Time on Sunday, September 4, 1977, Tom Yu received a phone call from Carlos Jon that members of the rival Wah Ching gang, including Michael "Hot Dog" Louie, one of its leaders, were present at the Golden Dragon restaurant in San Francisco's Chinatown (Chinese: 三藩市華埠金龍大酒樓).[15] The Golden Dragon was chosen as the site not only because it was a favored hangout of the Wah Ching, it was also favored by Hop Sing Tong members and was co-owned by Jack Lee, a Hop Sing elder.[16][17]

Chester Yu, Curtis Tam, Melvin Yu, and Peter Ng, all members of the Joe Boys (Chung Ching Yee) gang, took firearms and ammunition from a closet in a friend's home in Pacifica, where they had been staying that weekend, and Chester Yu drove the group to the restaurant in the Dodge that had been stolen earlier that evening by Peter Cheung and Dana Yu.[14] Forty minutes later, at 2:40 a.m., Chester Yu parked the stolen car near the Golden Dragon and stayed in the driver's seat while the others went to the restaurant. Armed with a .45-caliber Commando Mark III rifle (a modern clone of the Thompson submachine gun), two 12 gauge pump-action shotguns, and a .38-caliber revolver,[18] Curtis Tam, Melvin Yu, and Peter Ng donned nylon stocking masks, and entered the restaurant, looking for members of the Wah Ching. During the trial of Curtis Tam, Chester Yu testified that Tam was wielding a shortened shotgun, Ng had a long-barreled shotgun and a handgun, and Melvin Yu was using the rifle.[14][19] From 50[6] to more than 100 people,[18] many of whom were tourists, were present at the restaurant at the time of the shooting.[20]

Shots fired

According to Chester Yu, Ng had instructed Tam to fire a shot in the ceiling first so that "when the people panic and get down on the floor, we will decide who to shoot." Instead, without warning, the three randomly opened fire on the patrons inside the crowded restaurant, killing five people, including two tourists, and wounding 11 others, none of whom was a gang member.[14] In Tam's confession, he stated he had been forced to join the shooting and deliberately did not target any patrons; he "heard Melvin start shooting, then Peter. I fired my first shot at the sofa. The second I aimed where nobody was."[13] Testimony at Melvin Yu's trial showed he was the first to open fire.[21]

.jpg)

_(cropped).jpg)

According to unofficial sources, the gunman wielding the rifle (later identified as Melvin Yu)[21] was the first to open fire, walking directly up to a man at a table and shooting him, continuing to shoot after he had fallen to the floor. After the victim was shot nine times, Melvin Yu then redirected his automatic rifle randomly into the crowd, accompanied by two shotgun blasts from the other gunmen.[18] The first victim, later identified as Paul Wada, a visiting law student, may have been misidentified as a known gang sympathizer. An initial news report incorrectly identified other shooting victims as "highly placed" gang members.[22] The intended targets among the leadership of the Wah Ching and Hop Sing, who were sitting at a table at the back of the restaurant, were not injured.[23]

Up to 10 members of the Wah Ching, including their leader Michael Louie, ducked under tables during the gunfire.[6][20] They had been alerted by a friend, who had spotted the three gunmen running toward the restaurant from a window in the front of the restaurant and shouted "Man with a gun!" in Cantonese and English.[23] Triad member Raymond Kwok Chow, then 17 years old and a member of the allied Hop Sing Tong, was among those who survived the attack.[24]

The shooting lasted less than 60 seconds.[18] Police later called it the worst mass murder in San Francisco history.[9]

Comedians Philip Proctor and Peter Bergman of the Firesign Theatre were eating at the Golden Dragon during the shooting, after performing a Proctor and Bergman show at the Great American Music Hall. When Army veteran Bergman realized the perpetrators had emptied their weapons, he rose from cover in time to see their faces as they exited. He later testified in their conviction.[25]

Two armed law enforcement officers were also at the Golden Dragon during the attack. James Bonanno, a restaurant patrolman, dove for cover when the gunmen entered; he later testified he pulled his revolver and radioed for help, but since the shooting only took place over 30 to 45 seconds, it was over when he emerged and so he turned his efforts to helping wounded diners. Richard Hargens also fell to the floor after hearing shots and though he drew his revolver, he was unable to shoot the gunmen because other people were in his line of fire. Neither man was able to identify the gunmen beyond describing them as "young Orientals".[26]

Cleaning up

Chester Yu drove the shooters back to the house in Pacifica after the shooting,[15][14][19][27] and the weapons were returned to the closet.[14] After returning to Pacifica, the Joe Boys stayed awake until dawn discussing the shooting,[13] then slept for a few hours before awakening to hear the news of the killing.[15] They dispatched Tony Chun-Ho Szeto, another Joe Boy, to pick up noodles from the Golden Dragon for breakfast.[13] Later that morning, the perpetrators retrieved the weapons from the closet, cut them into pieces in the garage, and asked Szeto to dump the pieces into San Francisco Bay. Szeto drove Chester Yu to a location within sight of Kee Joon's, a Burlingame restaurant where Szeto worked, and together they dumped the parts into the Bay near San Francisco International Airport.[14][15] A week after the shooting, Tom Yu called Carlos Jon for the last time, asking Jon to "keep cool."[14]

Victims

The five victims fatally shot at the restaurant were later identified as:[6][28]

- Calvin M. Fong (方凱文), 18, a graduate of Archbishop Riordan High School[29]

- Donald Kwan (君唐勞), 20, a graduate of Abraham Lincoln High School[29]

- Denise Louie (雷典禮), 21, an urban planning student at the University of Washington[29]

- Paul Wada (和田保羅), 25, a law student at the University of San Francisco[29]

- Fong Wong (黃芳), 48, an immigrant from Hong Kong working as a waiter at the Golden Dragon[29]

Aftermath

One week after the shooting, two members of the Joe Boys were shot by suspected Wah Ching gunmen, leaving one Joe Boy dead and the other critically wounded, in what police called a revenge-motivated shooting.[30][31] Michael Lee, 18, was killed and Lo "Mark" Chan, 19, was wounded critically in an ambush at the entryway of Chan's Richmond District home.[32]

Nighttime tourism in Chinatown was depressed as restaurant reservations were cancelled en masse following the shooting. Although the Golden Dragon reopened just seven hours after the shooting,[33] it closed as early as 10 P.M. in the week following a drop in patronage that would normally keep it open until 3 A.M.[30] Business and tourist traffic remained depressed for several weeks following the shootings,[34] although other immigrants stated the rising cost of labor in Chinatown was to blame for increased prices and decreased business.[35] By December, business at the Golden Dragon had slumped and police had still not made any arrests, although Michael Louie, the Wah Ching leader that was reportedly targeted that night, had been arrested for suspected involvement with the 1976 murder of Kit Mun Louie (no relation), an 18-year-old immigrant from Hong Kong.[36][37]

Investigation

Chinatown has been ignored by the rest of the community for decades. It’s a low income area where the people crowded in are not afforded proper education, health and housing. It's treated like a ghetto. And like any poor district, it’s given low priority by the San Francisco Police Department.

Most of the kids committing the crimes are teenagers. They suffer from a lack of facilities. There are only two playgrounds for 30.000 people. The only football field is one where you skin your elbow on concrete.

Until recently, there were no Chinese cops and only one Chinese fireman. And not many Chinese lawyers.

The Chinese are not different than other people. We are law-abiding, life-is-good-to-us folks. My worry is that a lot of kids are going to get contaminated by these hoodlums.

— Supervisor Gordon J. Lau, 1977 Desert Sun article[12]

Chinatown residents came forward to provide tips in the days following the shooting. The presence of Wah Ching diners and Joe Boys assailants were identified almost immediately.[33][28] The San Francisco Police Department (SFPD) announced they were close to solving the crime soon after the shooting, but Chief Charles Gain criticized the Chinatown community for its silence and "abdication of responsibility" due to "the subculture of fear" of gang reprisals.[30] Gordon Lew, an editor of a local Chinatown newspaper, in turn criticized SFPD for relying on information and cooperation from community leaders linked to the underworld, leading to community distrust of SFPD, and concluded that "committing suicide is not a virtue among the Chinese".[30] Joe Fong, former head of the Joe Boys, said in an interview from prison that SFPD officers had been paid to protect gambling operations in Chinatown, which Chief Gain disputed as part of the police culture prior to his ascension to chief.[34] SFPD Lieutenant Daniel Murphy, head of the investigation, said "because so many innocent people were killed and injured, this time we have been getting more cooperation out of the residents and witnesses in Chinatown than we normally do."[9]

Mayor George Moscone announced a US$25,000 (equivalent to $101,000 in 2017) reward for information leading to the conviction of the shooters two days after it occurred, the largest reward offered to date.[28][38] The unprecedented reward was eventually increased to US$100,000 (equivalent to $404,000 in 2017) in late September, the highest reward allowed by city law.[39][34] It was eventually collected by Gan Wah "Robert" Woo, a Joe Boys member.[40][41] Woo had been arrested in March 1978 for his role in a February 15 Portsmouth Square shooting that left two Wah Ching members wounded.[42] He provided a recording of Tam conversing about the massacre to the police, was kept in protective custody after he had been identified as the informant.[43]

Woo provided the first lead in the case two weeks after the shooting, pointing the police to Curtis Tam.[29] However, by December 1977, no arrests had been made, though police were investigating the deadly rivalry between the Joe Boys and Wah Ching.[44]

Arrests

Five men, all members of the Joe Boys, were eventually arrested and convicted for the massacre: Curtis Tam, Melvin Yu, Peter Ng, Chester Yu, and Tom Yu; the gunmen were identified as Ng, Melvin Yu, and Tam, all 17 years old at the time of the shooting.[45]

Curtis Tam was the first to be arrested on March 24, 1978.[13][31] Tam, an emigrant from Hong Kong, was 18 years old and attending Galileo High School at the time of his arrest.[20][46] Shortly after his arrest, anonymous sources identified Tam as one of the gunmen.[47] Robert Woo, a police informant, recorded Tam recounting details of the attack, which led to his arrest.[13] During the interrogation after his arrest, Tam confessed and implicated 11 other participants.[5] The recording of Tam's interrogation was first played at an arraignment hearing in May 1978[13] and again at his trial; he claimed "They made me do it. If I didn't shoot somebody then they'd say, you know, I'm chicken. I don't think I shot anybody 'cause I didn't aim at anybody."[48] A hearing was held in April 1978 to determine if Tam should be tried as an adult,[49] which was granted.[50]

In early April 1978, the Yu brothers (Tom, Chester, and Dana) hired an attorney, George Walker, to make a plea bargain; in turn, their attorney met with the assigned assistant district attorney, Hugh Levine, on April 3 and explained his three unnamed clients were requesting immunity for two brothers (Tom and Dana Yu) in exchange for their testimony against the shooters.[14] Walker described those two brothers as peripherally involved, specifically calling Tom Yu "a peripheral figure who had inadvertently answered a telephone call at the house in Pacifica" which had informed him that members of the Wah Ching and Hop Sing were at the Golden Dragon. The third brother, Chester, admitted to his role as the getaway driver, but was requesting his proceedings to be held in juvenile court in exchange for his testimony. Levine agreed to allow the driver to enter juvenile court and provide immunity to the two brothers, conditioned upon the positive confirmation that (1) they were only peripherally involved in the crime and (2) their testimony was truthful.[14] Levine met Walker's three clients for the first time on April 19; Dana Yu's request for immunity was granted, and Chester Yu was allowed to enter the juvenile court system. However, since Levine already knew that Tom Yu, as a leader in the Joe Boys, could not have been involved only peripherally, immunity for Tom Yu alone was rejected.[14]

The weapons used in the attack were recovered by police divers from San Francisco Bay on April 20, 1978 after Chester Yu showed them where they had been dumped.[3][15][51] Chester also mentioned that a "Carlos" had called the house in Pacifica, resulting in the use of Carlos Jon as a witness for the prosecution.[14] At a preliminary hearing in May 1978, Tony Szeto described "bungled efforts to dump a bagful of guns".[52] Ballistics tests matched the recovered weapons with bullets taken from those killed.[14]

On April 21, SFPD announced the arrests of Peter Ng and an unnamed juvenile (later identified as the driver of the getaway car, Chester Yu), and named Melvin Yu as another suspect they were seeking in connection with the massacre.[53] Melvin Yu and Peter Cheung were arrested early on the morning of April 23, 18 miles (29 km) east of Carson City, Nevada.[54] Tom Yu dropped George Walker as his attorney and surrendered to police after the Memorial Day weekend.[14] In all, nine were arrested and scheduled to be tried for their roles in the massacre: Curtis Tam, Peter Ng, Tom Yu, Melvin Yu, Kam Lee, Chester Yu, Tony Szeto, Peter Cheung, and Donald Wong.[55]

Trials

Three youths who were charged with being accessories to the crimes had been found guilty or pleaded guilty in closed juvenile court proceedings by August 1978.[56]

Tam was scheduled to go on trial on July 31, 1978,[5] but the trial was delayed while a change of venue was being contemplated.[55] Tam's trial began on August 21,[56] and he was convicted on five murder counts and eleven assault counts on September 5, 1978.[46] Attorneys for the defendant made several motions to move the trial venue,[57] sequester the jury, and ban reporters from the courtroom, none of which were granted.[58] During his trial, Tam testified he had deliberately aimed his shotgun away from diners and only participated in the shooting under duress.[59] However, Chester Yu testified that Tam was "very happy" after the shooting and recalled hearing Tam say he "wanted to shoot more people",[19] and Tam was recorded by Robert Woo making a threat on the life of a suspected police informant.[60]

Thirteen eye witnesses were called to testify at Tam's trial, including eight of the eleven wounded; none identified Curtis Tam as one of the gunmen, although the witness who initially spotted the trio running toward the restaurant identified Peter Ng from a police photograph.[23] The prosecutors rested their case against Tam on August 29 after playing a recording of his confession, taken after his arrest on March 24.[48] Attorneys made closing arguments on September 1, and after the Labor Day weekend, the jury reconvened on September 5;[61] after deliberating for just over a day, the jury found Tam guilty of five counts of second degree murder, eleven counts of assault, and several weapons possession charges.[46] Tam faced a sentence of up to 35 years imprisonment, but a defense attorney vowed to appeal the verdict, which he called "a compromise" because he thought "[the jury] considered duress in reducing their finding of intent on Tam's part". The sentencing hearing was set for October 3.[59][62] Tam received a sentence of 28 years imprisonment.[63] On June 18, 1981, the California Court of Appeals reduced his sentence to 23 years. Tam filed another appeal in August 1981.[64]

After Tam's trial, Tom Yu, Melvin Yu, and Peter Ng stood trial.[59] On September 26, 1978, Melvin Yu was convicted after four hours of deliberation of five counts of first-degree murder and 11 counts of assault with a deadly weapon; his attorney offered no defense against the charges, and Melvin Yu did not testify at his trial.[21][65] He received a life sentence.[63]

Peter Ng went on trial on January 8, 1979 in Fresno,[66] and was convicted on February 22 of five counts of first degree murder and eleven counts of assault with a deadly weapon.[63][67] Jurors deliberated four hours before reaching the verdict.[68]

Tom Yu was indicted but moved to dismiss the charges on the basis that he had been granted immunity by Levine; the trial court denied the motion, finding both that he had not satisfied the two imposed conditions, and further, that his proposed testimony was not true.[14] Yu then entered a conditional guilty plea in 1979 on one count of conspiracy to commit second-degree murder and admitted that a firearm was used in the crime.[66] The plea bargain had been extended to Tom Yu on April 25, 1978, modified on May 30, and accepted by Yu on September 1.[14] However, upon reviewing the probation report, which called Tom Yu "the prime mover in the whole thing", the court rejected the plea bargain and restored the original charges.[68] Yu appealed the rejection of the plea bargain, since the court had previously ruled it was a binding agreement, although the presiding judge also added the condition that court judgment could be used to set it aside.[14] The trial venue had been moved first to Fresno due to publicity in San Francisco, and then to Santa Barbara since Peter Ng had already been tried and convicted in Fresno. Yu's first trial ended in a hung jury in September 1979.[69] He was later convicted of five counts of first degree murder, eleven counts of assault by means of force likely to produce great bodily injury, one count of conspiracy to commit murder, and one count of conspiracy to commit assault with a deadly weapon. He was sentenced to life imprisonment in state prison.[14]

Release and parole

In October 1991, Curtis Tam was released from prison.[67]

In 2014, Melvin Yu was granted parole, and during the parole hearing, he said that he had plans to live with a cousin in Hong Kong and expected to be deported back to there. Although, as of 2017, a spokesperson for the Chinese Consulate of San Francisco states that there is no record for deportation requests for Yu, and Yu has been living in San Francisco.[67]

Tom Yu is eligible for parole in 2017.[67]

Peter Ng can seek parole in 2020, after being denied eight times, most recently in 2015.[67]

Long term results

_(cropped).jpg)

An ex-Joe Boys member, Bill Lee, wrote about the killings and his life as a Joe Boys gangster in his book, Chinese Playground: A Memoir.

The Golden Dragon Massacre led to the establishment of the SFPD's Asian Gang Task Force,[42][70] credited with ending gang-related violence in Chinatown by 1983.[71]

Michael Louie, the reputed leader of the Wah Ching who was targeted that night, was off the streets after he was arrested on December 5, 1977 for the murder of Kit Mun Louie (no relation) which occurred on August 29, 1976.[36][72] Michael Louie had been romantically involved with the 18-year-old immigrant from Hong Kong, but he confessed to being angry with her for "whoring around with Joe Boys". In order to frighten her, he put what he thought was an unloaded gun to her head as she was sleeping and pulled the trigger. Although he had removed the clip, he neglected to check the firing chamber, which was still loaded with a live round when he shot her at point-blank range. To cover the crime, he scattered pieces of the weapon in San Francisco Bay and dumped her body near Stinson Beach, where it was discovered on January 1, 1977, but not identified until November 1977. Michael Louie pleaded guilty to voluntary manslaughter and possession of a deadly weapon after his arrest,[37] receiving a sentence of 15 years imprisonment in January 1978.[73]

Robert Woo, the informant who collected the $100,000 reward, was killed during a shootout with police while robbing a jewelry shop in Los Angeles on December 19, 1984.[41][74]

The Golden Dragon restaurant continued operation shortly after the massacre, but patronage was down and it failed a health inspection in September 1978.[75] After failing another health inspection in January 2006 it was closed. The restaurant also owed a year's worth of paychecks to its employees.[16][76] It was reopened as the Imperial Palace Restaurant.[77]

See also

- List of massacres in the United States

- Wah Mee massacre, a similar mass shooting in Seattle

- 101 California Street shooting, another mass murder that took place a short distance away from the Golden Dragon, in San Francisco's financial district, in 1993.

References

- ↑ Donat, Hank (2002). "Notorious SF: Golden Dragon Massacre". MisterSF. Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- ↑ King, Peter H. (11 September 1977). "Chinatown War Moves Above Ground". Santa Cruz Sentinel. AP. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- 1 2 "SF Police Seek To Return Two Charged In Chinatown Slayings". Santa Cruz Sentinel. AP. 24 April 1978. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- ↑ "Chinatown Gang Leader Was Target". Santa Cruz Sentinel. AP. 7 September 1977. Retrieved 5 June 2018.

- 1 2 3 "Trial Set in Golden Dragon Deaths". Ocala Star-Banner. Associated Press. July 31, 1978. Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 "Chinatown massacre victims were just innocent bystanders". Lodi News-Sentinel. UPI. 6 September 1977. Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- ↑ "1 Dead in Chinatown Shootings". San Mateo Times. AP. 5 July 1977. Retrieved 7 June 2018. (subscription required)

- ↑ "Youth is Slain Trying to Flee His Assailant". Santa Cruz Sentinel. AP. 1 June 1977. Retrieved 5 June 2018.

- 1 2 3 "San Francisco Police Fear Reprisal In Slayings Laid to Chinese Gangs". The New York Times. 6 September 1977. Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- ↑ Calhoun, Bob (28 August 2017). "Yesterday's Crimes: The War for Chinatown". SF Weekly. Retrieved 4 June 2018.

- ↑ McClure, Michael (1983). "The Death of Kin Chuen Louie". Fragments of Perseus. New York City: New Directions Publishing Corporation. pp. 19–21. Retrieved 4 June 2018.

- 1 2 "San Francisco's Recent Chinatown Killings". Desert Sun. NEA. 26 September 1977. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Tape Details Planning For Chinatown Raid". Santa Cruz Sentinel. AP. 4 May 1978. Retrieved 5 June 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 People v. Yu, 143 Cal. App. 3d 358 (Court of Appeals of California, Second District, Division Two 26 May 1983).

- 1 2 3 4 5 People v. Szeto, 29 Cal. 3d 20 (Supreme Court of California 11 February 1981).

- 1 2 Hua, Vanessa (11 May 2006). "Workers want pay from Dragon / Back wages claimed as restaurant reopens under new name". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- ↑ Bill Lee. "The Tongs of Chinatown" (Interview). Interviewed by Michael Zelenko. FoundSF. Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 "Chinatown Attack Kills 5, Wounds 10 In San Francisco". The New York Times. 5 September 1977. Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- 1 2 3 "Golden Dragon massacre tale told". San Bernardino Sun. AP. 27 August 1978. Retrieved 5 June 2018.

- 1 2 3 "Make First Arrest in Golden Dragon Massacre of 1977". The Hour. UPI. March 24, 1978. Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- 1 2 3 "18-Year-Old Is Convicted In Golden Dragon Deaths". Santa Cruz Sentinel. AP. 27 September 1978. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- ↑ "Chinese Gang War Erupts In Shooting". Desert Sun. AP. 5 September 1977. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- 1 2 3 "Gang Members Tell How They Escaped Bullets In Massacre". Santa Cruz Sentinel. AP. 24 August 1978. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- ↑ Mozingo, Joe (27 March 2014). "In Yee case, a figure of many faces". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- ↑ "Proctor & Bergman "On The Road"". Firezine. Vol. 1 no. 5. Spring 1999. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- ↑ "Two Lawmen Describe Chinatown Massacre". Santa Cruz Sentinel. AP. 23 August 1978. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- ↑ Stolberg, Sheryl (14 September 1995). "COLUMN ONE : School's Out for Convicts : Taxpayers have stopped paying for inmates' college degrees in a backlash against prison reform. Corrections officials decry the loss of a powerful rehabilitation tool". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 9 February 2014.

- 1 2 3 "$25,000 Reward Offered For Killers". Santa Cruz Sentinel. AP. 6 September 1977. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Sernoffsky, Evan (1 September 2017). "SF's Golden Dragon massacre: 40 years later, victims still have scars". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 8 June 2018. (subscription required)

- 1 2 3 4 "San Francisco Ambush Called Chinese Gang Revenge". The New York Times. 12 September 1977. Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- 1 2 "Arrest in Chinatown massacre". San Bernardino Sun. AP. 25 March 1978. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- ↑ "Two shot in gang reprisal". San Bernardino Sun. AP. 12 September 1977. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- 1 2 "Chinatown Residents Aid Hunt For Killers". Desert Sun. AP. 6 September 1977. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- 1 2 3 Turner, Wallace (2 October 1977). "Coast Chinatown Seeks to Still Fears". The New York Times. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- ↑ Ledbetter, Les (13 February 1978). "Year of Horse a Time of Change For Chinatowns Across Nation". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- 1 2 "Chinatown Gunfire Echoes Through SF". Santa Cruz Sentinel. AP. 12 December 1977. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- 1 2 "Chinatown Gang Leader Enters Plea Of Guilty". Santa Cruz Sentinel. AP. 21 December 1977. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- ↑ "$25,000 Reward Offered In 5 Slayings on Coast". The New York Times. AP. 7 September 1977. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- ↑ "$100,000 Chinatown Reward". Santa Cruz Sentinel. AP. 21 September 1977. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- ↑ "Services held for slain officer". Santa Cruz Sentinel. AP. 23 December 1984. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- 1 2 Wood, Tracy (29 November 1987). "Courtroom Testimony Unveils Events Leading to Chinatown Murders". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- 1 2 "Chinatown Gang Member Charged With Shootings". Santa Cruz Sentinel. AP. 15 March 1978. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- ↑ "Informant protected". San Bernardino Sun. AP. 1 May 1978. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- ↑ King, Peter H. (13 December 1977). "Killings Echo". Desert Sun. Associated Press. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- ↑ "3 Accused in California In Killing of 5 in Chinatown". New York Times. UPI. 22 April 1978. Retrieved 10 February 2014.

- 1 2 3 "Chinese immigrant guilty in murders". Gadsden Times. Associated Press. 7 September 1978. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- ↑ "Chinatown youth said triggerman". San Bernardino Sun. AP. 27 March 1978. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- 1 2 "Golden Dragon Suspect To Take Stand At Trial". Santa Cruz Sentinel. AP. 30 August 1978. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- ↑ "Golden Dragon Hearing". Santa Cruz Sentinel. AP. 12 April 1978. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- ↑ "SF Police Convinced Killers Are In Custody". Santa Cruz Sentinel. AP. 23 April 1978. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- ↑ Mullen, Kevin J. "The Golden Dragon Restaurant Massacre". FoundSF. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- ↑ "Golden Dragon Trial Ordered". Santa Cruz Sentinel. AP. 17 May 1978. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- ↑ "Police seek fourth youth in Chinatown massacre". San Bernardino Sun. AP. 23 April 1978. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- ↑ "Two more arrests made in Chinatown massacre". San Bernardino Sun. AP. 24 April 1978. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

- 1 2 "Golden Dragon Slaying Trial Venue Change Asked". Santa Cruz Sentinel. AP. 31 July 1978. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- 1 2 "Prosecution Attempts To Recreate Massacre". Santa Cruz Sentinel. AP. 25 August 1978. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- ↑ "Golden Dragon Change Of Venue Denied By Judge". Santa Cruz Sentinel. AP. 23 June 1978. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- ↑ "Judge Denies Move To Ban the Press". Santa Cruz Sentinel. AP. 18 August 1978. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- 1 2 3 "Chinatown Killer Found Guilty By Jury". Santa Cruz Sentinel. AP. 6 September 1978. Retrieved 5 June 2018.

- ↑ "Golden Dragon Trial Closing Arguments Set". Santa Cruz Sentinel. AP. 1 September 1978. Retrieved 5 June 2018.

- ↑ "Golden Dragon Jury To Reconvene Today". Santa Cruz Sentinel. AP. 5 September 1978. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- ↑ Chuh, Teresa (6 September 1978). "18-year-old guilty in massacre". San Bernardino Sun. Associated Press. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- 1 2 3 "Gang member convicted of 5 murders". San Bernardino Sun. AP. 23 February 1979. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- ↑ "Golden Dragon Appeal Filed". Santa Cruz Sentinel. AP. 5 August 1981. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- ↑ "Massacre Suspect Convicted". Toledo Blade. Associated Press. September 27, 1978. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- 1 2 "Guilty plea entered in Chinatown slayings". San Bernardino Sun. AP. 7 January 1979. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Sernoffsky, Evan (September 3, 2017). "Freed killer in Golden Dragon massacre: It will take 'lifetimes to make amends'". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 19 September 2017. (subscription required)

- 1 2 "Golden Dragon Defendant Guilty". Santa Cruz Sentinel. AP. 23 February 2018. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- ↑ "Golden Dragon Jury Deadlocks". Santa Cruz Sentinel. AP. 7 September 1979. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- ↑ Koopman, John (16 September 2007). "2 sons of Chinatown patrol Asian gangs for S.F. police". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- ↑ "Squad reduces Chinatown violence on coast". The New York Times. UPI. 23 September 1983. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- ↑ "Chinatown still suffering from September's gunfire". San Bernardino Sun. AP. 13 December 1977. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

- ↑ "S.F. Gang Leader Sentenced". Santa Cruz Sentinel. AP. 26 January 1978. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- ↑ Butterfield, Fox (13 January 1985). "Chinese organized crime said to rise in U.S." The New York Times. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- ↑ "Famed SF Restaurant Unsanitary". Santa Cruz Sentinel. AP. 15 September 1978. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

- ↑ "Opinion: Long-overdue paychecks". San Francisco Chronicle. 25 March 2005. Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- ↑ Hua, Vanessa (7 October 2006). "Restaurant must pay $1 million to workers". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 19 September 2017. .

External links

- Morris, Brockman (2000). Bamboo Tigers: of San Francisco Chinatown's Golden Dragon Massacre 1977. self. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- Kamiya, Gary (8 July 2016). "Chinatown gang feud ignited one of SF's worst mass homicides". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 12 October 2017. (subscription required)

- Notes Underworld, AsianWeek