Gigantopithecus

| Gigantopithecus | |

|---|---|

| |

| G. blacki lower mandible cast | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Family: | Hominidae |

| Subfamily: | Ponginae |

| Genus: | †Gigantopithecus von Koenigswald, 1935[1] |

| Type species | |

| Gigantopithecus blacki von Koenigswald, 1935 | |

| Species | |

|

†G. blacki | |

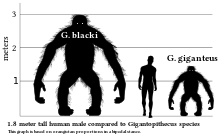

Gigantopithecus (from the Ancient Greek γίγας gigas "giant", and πίθηκος pithekos "ape") is an extinct genus of ape that existed from perhaps nine million years to as recently as one hundred thousand years ago,[2] in what is now India, Vietnam, China and Indonesia placing Gigantopithecus in the same time frame and geographical location as several hominin species.[3][4] The primate fossil record suggests that the species Gigantopithecus blacki were the largest known primates that ever lived, standing up to 3 m (9.8 ft) and weighing as much as 540–600 kg (1,190–1,320 lb),[2][5][6][7] although some argue that it is more likely that they were much smaller, at roughly 1.8–2 m (5.9–6.6 ft) in height and 180–300 kg (400–660 lb) in weight.[8][9][10][11]

Taxonomy

The first Gigantopithecus remains described by an anthropologist were found in 1935 by Ralph von Koenigswald in an apothecary shop. Fossilized teeth and bones are often ground into powder and used in some branches of traditional Chinese medicine.[12] Von Koenigswald named the theorized species Gigantopithecus.[8]

Since then, relatively few fossils of Gigantopithecus have been recovered. Aside from the molars recovered in Chinese traditional medicine shops, Liucheng Cave in Liuzhou, China, has produced numerous Gigantopithecus blacki teeth, as well as several jawbones.[13] Other sites yielding significant finds were in Vietnam and India.[3][6] These finds suggest that the range of Gigantopithecus was in southeast Asia. There are presently three extinct named species of Gigantopithecus: G. blacki, G. bilaspurensis, and G. giganteus.

In 1955, 47 G. blacki teeth were found among a shipment of "dragon bones" (also called "oracle bones") in China. Tracing these teeth to their source resulted in the recovery of more teeth and a rather complete large mandible. By 1958, three mandibles and more than 1,300 teeth had been recovered. Gigantopithecus remains have come from sites in Hubei, Guangxi, and Sichuan, from warehouses for Chinese medicinal products, as well as from cave deposits. Not all Chinese remains have been dated to the same time period, and the fossils in Hubei appear to be of a later date than elsewhere in China. The Hubei teeth are also larger.[14]

Chinese physical anthropologist and paleoprimotologist Dong Tichen suggested that Gigantopithecus bears a series of quite distinctly differentiated characteristics of its own. Thus it stands for a completely independent branch on the primate genealogical tree. Tichen considered Gigantopithecinae as a new subfamily, with Gigantopithecus as its type genus, which logically belongs to Pongidae, not to Hominidae.[15]

Gigantopithecus blacki (named in honour of the friend and colleague of von Koenigswald, Davidson Black[16]) is known only through fossil teeth and mandibles found in cave sites in South China and Vietnam. These are appreciably larger than those of living gorillas, but the exact size and structure of the rest of the body can only be estimated in the absence of additional findings. Dating methods have shown that G. blacki existed for at least a million years, going extinct about 100,000 years ago after having been contemporary with anatomically modern humans (Homo sapiens) for tens of thousands of years, and co-existing with H. erectus, who preceded the appearance of H. sapiens.[3] In 2014, for the first time, fossil teeth and mandible of Gigantopithecus blacki were found in Indonesia.[17][18]

Some of the caves in which teeth have been found were not caves yet at the time the apes lived, but just fissures. It has been suggested that Gigantopithecus bones were brought there by porcupines, who chew on bones as a source of calcium. This may help explain the lack of Gigantopithecus bones today.[19][11]

Evolution

In the past, Gigantopithecus blacki (G. blacki) was thought to be closely related to early hominins, particularly Australopithecus, on the basis of molar evidence; this is now regarded a result of convergent evolution.[20] Gigantopithecus is now placed in the subfamily Ponginae along with the orangutan.[21]

Gigantopithecus bilaspurensis (G. bilaspuresis) is a very large fossil ape identified from a few jaw bones and teeth from India. This species lived about 6 to 9 million years ago in the Miocene. It is related to G. blacki.

Dating to roughly five million years before G. blacki, a separate species, Gigantopithecus giganteus (G. giganteus), is known from extremely fragmentary remains from northern India and China. In the Guangxi region of China, teeth of this species were discovered in limestone formations in Daxin and Wuming, north of Nanning. Despite the name, G. giganteus is believed to have been about half the size of G. blacki.[5][6] Based on the slim fossil finds, it was a large, ground-dwelling herbivore that ate primarily bamboo and foliage.

Description

Gigantopithecus's method of locomotion is uncertain, as no pelvic or leg bones have been found. The dominant view is that it walked on all fours like modern gorillas and chimpanzees; however, a minority opinion favors bipedal locomotion. This was most notably championed by the late Grover Krantz, but this assumption is based only on the very few jawbone remains found, all of which are U-shaped and widen towards the rear. This allows room for the windpipe to be within the jaw, allowing the skull to sit squarely on a fully erect spine as in modern humans, rather than roughly in front of it, as in the other great apes.

The majority view is that the weight of such a large, heavy animal would put enormous stress on the creature's legs, ankles, and feet if it walked bipedally; while if it walked on all four limbs, like gorillas, its weight would be better distributed over each limb.

Based on the fossil evidence, adult male Gigantopithecus blacki are believed to have stood about 3 m (9.8 ft) tall and weighed as much as 540–600 kg (1,190–1,320 lb),[2][5][6][7] making the species three to four times as heavy as modern gorillas and seven to eight times as heavy as the orangutan, its closest living relative. Large males may have had an armspan of over 3.6 m (11.8 ft). The species was highly sexually dimorphic, with adult females roughly half the weight of males.[6] Because of wide interspecies differences in the relationship between tooth and body size, some argue that it is more likely that adult male Gigantopithecus blacki were much smaller, at roughly 1.8–2 m (5.9–6.6 ft) in height and 180–300 kg (400–660 lb) in weight.[8][9][10][11]

Its appearance is not known, because of the fragmentary nature of its fossil remains. It possibly resembled modern gorillas, because of its supposedly similar lifestyle. Some scientists, however, think it probably looked more like its closest modern relative, the orangutan. Based on the upper estimates, Gigantopithecus possibly had few or no enemies when fully grown. However, younger, weak, or injured individuals may have been vulnerable to predation by big cats, large constrictor snakes, crocodiles, machairodonts, hyenas, and Homo erectus. Based on the lower estimates, however, even fully grown individuals may have been vulnerable to predation by all the animals mentioned above other than large snakes.

Paleobiology

The genus lived in Asia and probably inhabited bamboo forests, since its fossils are often found alongside those of extinct ancestors of the giant panda. Most evidence points to Gigantopithecus being a herbivore.

Diet

The jaws of Gigantopithecus are deep and very thick. The molars are low-crowned and flat, and exhibit heavy enamel suitable for tough grinding.[22] The premolars are broad and flat and configured similarly to the molars. The canine teeth are neither pointed nor sharp, while the incisors are small, peglike, and closely aligned. The features of teeth and jaws suggested that the animal was adapted to chewing tough, fibrous food by cutting, crushing, and grinding it. Gigantopithecus teeth also have a large number of cavities, similar to those found in giant pandas, whose diet, which includes a large amount of bamboo, may be similar to that of Gigantopithecus.[5]

In addition to bamboo, Gigantopithecus consumed other vegetable foods, as suggested by the analysis of the phytoliths adhering to its teeth. An examination of the microscopic scratches and gritty plant remains embedded in Gigantopithecus teeth suggests that they fed on seeds and fruit, as well as bamboo.[14]

Extinction

Gigantopithecus may have become extinct approximately 100,000 years ago because the climate change during the Pleistocene era changed the plants from forest to savanna, and their food supply in fruits decreased. Gigantopithecus did not eat the grass, roots and leaves that were dominant food sources in the savanna.[23][24][25]

See also

References

- ↑ von Koenigswald, G. H. R. (1935). "Eine fossile Säugetierfauna mit Simia aus Südchina" (PDF). Proceedings of the Koninklijke Akademie van Wetenschappen te Amsterdam. 38 (8): 874–875.

- 1 2 3 Christmas, Jane (2005-11-07). "Giant Ape lived alongside humans". McMaster University. Retrieved 2007-12-06.

- 1 2 3 Ciochon, R.; et al. (1996). "Dated Co-Occurrence of Homo erectus and Gigantopithecus from Tham Khuyen Cave, Vietnam" (PDF). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 93 (7): 3016–3020. doi:10.1073/pnas.93.7.3016. PMC 39753. PMID 8610161. Retrieved 2007-12-06.

- ↑ Sofwan, N.; et al. (2016). "Primata Besar di Jawa: Spesimen Baru Gigantopithecus dari Semedo/Giant Primate of Java: A new Gigantopithecus specimen from Semedo" (PDF). Berkala Arkeologi. 36 (2): 141–160. Retrieved 2017-12-06.

- 1 2 3 4 Ciochon, R. (1991). "The ape that was – Asian fossils reveal humanity's giant cousin". Natural History. 100: 54–62. ISSN 0028-0712. Archived from the original on May 25, 2015. Retrieved 2007-12-06.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Pettifor, Eric (2000) [1995]. "From the Teeth of the Dragon: Gigantopithecus Blacki". Selected Readings in Physical Anthropology. Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company. pp. 143–149. ISBN 0-7872-7155-1. Retrieved 2008-01-30.

- 1 2 de Vos, J., 1993. Een portret van Pleistocene zoogdieren: Op zoek naar de reuzenaap (Gigantopithecus) in Vietnam. Cranium, 10(2), pp.123-127.

- 1 2 3 Relethford, J. (2003). The Human Species: An Introduction to Biological Anthropology. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-7674-3022-7.

- 1 2 Dennel, R. (2009). The Palaeolithic Settlement of Asia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-84866-4.

- 1 2 Singh, R. P.; Islam, Z. (2012). Environmental Studies. Concept Publishing Company Pvt. Ltd. ISBN 978-81-8069-774-6.

- 1 2 3 Zhang, Y. and Harrison, T., 2017. Gigantopithecus blacki: a giant ape from the Pleistocene of Asia revisited. American journal of physical anthropology, 162(S63), pp.153-177. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.23150.

- ↑ "How Gigantopithecus was discovered". The University of Iowa Museum of Natural History. Archived from the original on 2007-10-12. Retrieved 2007-12-06.

- ↑ Coichon, R. (1991). "The ape that was – Asian fossils reveal humanity's giant cousin". Natural History. 100: 54–62. ISSN 0028-0712. Archived from the original on May 25, 2015. Retrieved 2007-12-06.

- 1 2 Poirier, F.E.; McKee, J.K. (1999). Understanding Human Evolution (fourth ed.). Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall. p. 119. ISBN 0130961523.

- ↑ Tung, Tichen (1962), "The taxonomic position of gigantopithecus in primates", Vertebrata PalAsiatica, 6: 375–383

- ↑ Russell Ciochon. "The Ape That Was Asian fossils reveal humanity's giant cousin". University of Iowa. Archived from the original on December 30, 2012.

- ↑ Satwika Rumeksa (December 1, 2014). "Kingkong Setinggi 3 Meter Pernah Hidup di Tanah Jawa".

- ↑ Maryono, Agus (December 1, 2014). "Fossils of rare, ancient animals found in Tegal". The Jakarta Post. Retrieved December 1, 2014.

- ↑ Colin Barras (May 21, 2016). "Gigantopithecus: The story of the greatest of the great apes". New Scientist.

- ↑ Frayer, D. W. (1973). "Gigantopithecus and its relationship to Australopithecus" (PDF). American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 39 (3): 413–426. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330390310. PMID 4796262.

- ↑ [The Primata, 2007. Subfamily Ponginae. A Taxonomy of Extinct Primates. Accessed 21 February 2013.]

- ↑ Olejniczak, A.J.; et al. (2008). "Molar enamel thickness and dentine horn height in Gigantopithecus blacki" (PDF). American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 135 (1): 85–91. doi:10.1002/ajpa.20711. PMID 17941103. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-03.

- ↑ 05, Mark Strauss PUBLISHED January. "The Largest Ape That Ever Lived Was Doomed By Its Size". National Geographic News. Retrieved 2016-01-06.

- ↑ Bocherens, Hervé; Schrenk, Friedemann; Chaimanee, Yaowalak; Kullmer, Ottmar; Mörike, Doris; Pushkina, Diana; Jaeger, Jean-Jacques (2017). "Flexibility of diet and habitat in Pleistocene South Asian mammals: Implications for the fate of the giant fossil ape Gigantopithecus". Quaternary International. 434: 148. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2015.11.059.

- ↑ "Giant ape Gigantopithecus became extinct 100,000 years ago due to its inability to adapt". phys.org. phys.org. Retrieved 2016-01-06.

Further reading

- Park, Michael Alan. Biological Anthropology. Mayfield Publishing Co., 1996, ISBN 1-55934-424-5