Premolar

| Premolar | |

|---|---|

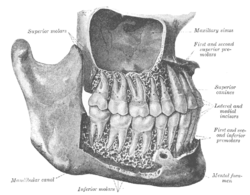

The permanent teeth, viewed from the right. | |

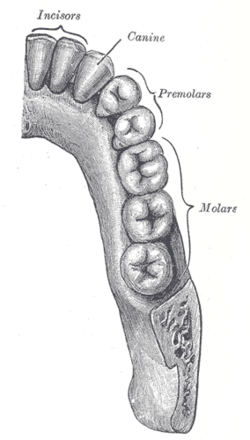

Permanent teeth of right half of lower dental arch, seen from above. | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | dentes premolares |

| MeSH | D001641 |

| TA | A05.1.03.006 |

| FMA | 55637 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

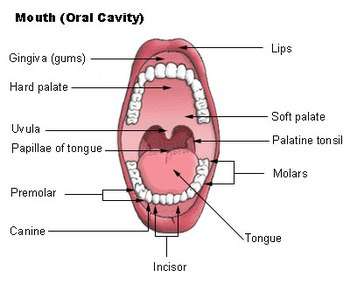

The premolar teeth, or bicuspids, are transitional teeth located between the canine and molar teeth. In humans, there are two premolars per quadrant in the permanent set of teeth, making eight premolars total in the mouth.[1][2][3] They have at least two cusps. Premolars can be considered as 'transitional teeth' during chewing, or mastication. They have properties of both the anterior canines and posterior molars, and so food can be transferred from the canines to the premolars and finally to the molars for grinding, instead of directly from the canines to the molars.[4]

Human anatomy

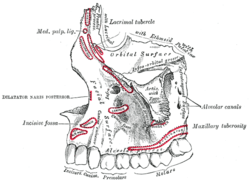

The premolars in humans are the maxillary first premolar, maxillary second premolar, mandibular first premolar, and the mandibular second premolar.[1][3] Premolar teeth by definition are permanent teeth distal to the canines, preceded by deciduous molars.[5]

Morphology

There is always one large buccal cusp, especially so in the mandibular first premolar. The lower second premolar almost always presents with two lingual cusps.[6]

The lower premolars and the upper second premolar usually have one root. The upper first usually has two roots, but can have just one root, notably in Sinodonts, and can sometimes have three roots.[7][8]

Other mammals

In primitive placental mammals there are four premolars per quadrant, but the most mesial two (closer to the front of the mouth) have been lost in catarrhines (Old World monkeys and apes, including humans). Paleontologists therefore refer to human premolars as Pm3 and Pm4.[9][10]

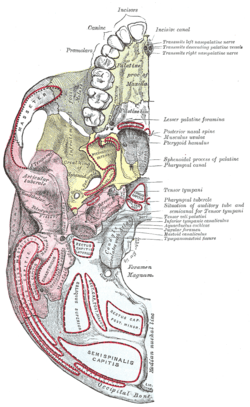

Additional images

See also

References

- 1 2 Roger Warwick & Peter L. Williams, eds. (1973), Gray’s Anatomy (35th ed.), London: Longman, pp. 1218–1220

- ↑ Weiss, M.L., & Mann, A.E (1985), Human Biology and Behaviour: An anthropological perspective (4th ed.), Boston: Little Brown, pp. 132–135, 198–199, ISBN 0-673-39013-6

- 1 2 Glanze, W.D., Anderson, K.N., & Anderson, L.E, eds. (1990), Mosby's Medical, Nursing & Allied Health Dictionary (3rd ed.), St. Louis, Missouri: The C.V. Mosby Co., p. 957, ISBN 0-8016-3227-7

- ↑ Weiss, M.L., & Mann, A.E. (1985), pp.132-134

- ↑ Warwick, R., & Williams, P.L. (1973), pp.1218-1219.

- ↑ Warwick, R., & Williams, P.L. (1973), p.1219.

- ↑ Standring, Susan (2015). Gray's Anatomy E-Book: The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 518. ISBN 9780702068515.

- ↑ Kimura, R. et al. (2009). A Common Variation in EDAR Is a Genetic Determinant of Shovel-Shaped Incisors. In American Journal of Human Genetics, 85(4). Page 528. Retrieved December 24, 2016, from link.

- ↑ Christopher Dean (1994). "Jaws and teeth". In Steve Jones, Robert Martin & David Pilbeam (eds.). The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Human Evolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 56–59. ISBN 0-521-32370-3. Also ISBN 0-521-46786-1 (paperback)

- ↑ Gentry Steele and Claud Bramblett (1988). The Anatomy and Biology of the Human Skeleton. p. 82. ISBN 9780890963265.