Field of Dreams

| Field of Dreams | |

|---|---|

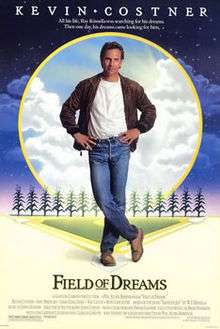

Promotional poster by Olga Kaljakin | |

| Directed by | Phil Alden Robinson |

| Produced by |

Lawrence Gordon Charles Gordon |

| Screenplay by | Phil Alden Robinson |

| Based on |

Shoeless Joe by W.P. Kinsella |

| Starring | |

| Music by | James Horner |

| Cinematography | John Lindley |

| Edited by | Ian Crafford |

| Distributed by |

Universal Pictures (United States) TriStar Pictures/Carolco Pictures (International) |

Release date |

|

Running time | 107 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $15 million[2][3] |

| Box office | $84.4 million[4] |

Field of Dreams is a 1989 American fantasy-drama sports film directed by Phil Alden Robinson, who also wrote the screenplay, adapting W. P. Kinsella's novel Shoeless Joe. It stars Kevin Costner, Amy Madigan, James Earl Jones, Ray Liotta and Burt Lancaster in his final film role. It was nominated for three Academy Awards, including for Best Original Score, Best Adapted Screenplay and Best Picture.

In 2017, the film was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[5]

Plot

Ray Kinsella is a novice Iowa farmer who lives with his wife, Annie, and daughter, Karin. In the opening narration, he explains how he had a troubled relationship with his father, John Kinsella, who had been a devoted baseball fan. While walking through his cornfield one evening, he hears a voice whispering, "If you build it, he will come." He continues hearing this before finally seeing a vision of a baseball diamond in his field. Annie is skeptical, but she allows him to plow the corn under in order to build a baseball field. As he builds, he tells Karin the story of the 1919 Black Sox Scandal. Months pass and nothing happens; his family faces financial ruin until, one night, Karin spots a uniformed man on the field. Ray recognizes him as Shoeless Joe Jackson, a deceased baseball player idolized by John. Thrilled to be able to play baseball again, Joe asks to bring others to the field to play. He later returns with the seven other players banned as a result of the 1919 scandal.

Ray's brother-in-law, Mark, can't see the players and warns him that he will go bankrupt unless he replants his corn. While in the field, Ray hears the voice again, this time urging him to "ease his pain."

Ray attends a PTA meeting at which the possible banning of books by radical author Terence Mann is discussed. He decides the voice was referring to Mann. He comes across a magazine interview dealing with Mann's childhood dream of playing for the Brooklyn Dodgers. After Ray and Annie both dream about him and Mann attending a baseball game together at Fenway Park, he convinces her that he should seek out Mann. He heads to Boston and persuades a reluctant, embittered Mann to attend a game with him at Fenway Park. While there, he hears the voice again, this time urging him to "go the distance." At the same time, the scoreboard "shows" statistics for a player named Archibald "Moonlight" Graham, who played one game for the New York Giants in 1922, but never had a turn at bat. After the game, Mann eventually admits that he, too, saw it.

Ray and Mann then travel to Chisholm, Minnesota where they learn that Graham had become a doctor and had died sixteen years earlier. During a late night walk, Ray finds himself back in 1972 and encounters the then-living Graham, who states that he had moved on from his baseball career. He also says that the greater disappointment would have been not having a medical career. He declines Ray's invitation to fulfill his dream; however, during the drive back home, Ray picks up a young hitchhiker who introduces himself as Archie Graham. While Archie sleeps, Ray reveals to Mann that John had wanted him to live out his dream of being a baseball star. He stopped playing catch with him after reading one of Mann's books at 14. At 17, he had denounced Shoeless Joe as a criminal to John and that was the reason for the rift between them. Ray expresses regret that he didn't get a chance to make things right before John died. When they arrive back at Ray's farm, they find that enough players have arrived to field two teams. A game is played and Archie finally gets his turn at bat.

The next morning, Mark returns and demands that Ray sell the farm. Karin says that they will not need to because people will pay to watch the ballgames. Mann agrees, saying that "people will come" in order to relive their childhood innocence. Ray, after much thought, refuses and a frustrated Mark scuffles with him, during which Karin is accidentally knocked off the bleachers. The young Graham runs from the field to help, becoming old Graham, complete with Gladstone bag, the instant he steps off of it, and saves Karin from choking (she had been eating a hot dog when she fell). Ray realizes that Graham sacrificed his young self in order to save her. After reassuring Ray that his true calling was medicine and being commended by the other players, Graham leaves, disappearing into the corn. Suddenly, Mark is able to see the players and urges Ray not to sell the farm.

After the game, Shoeless Joe invites Mann to enter the corn; he accepts and disappears into it. Ray is angry at not being invited, but Shoeless Joe rebukes him: if he really wants a reward for having sacrificed so much, then he had better stay on the field. Shoeless Joe then glances towards a player at home plate, saying "If you build it, he will come." The player then removes his mask, and Ray recognizes him to be his father, John, as a young man. Shocked, Ray realizes that "ease his pain" referred to his dad, and believes that Shoeless Joe was the voice all along; however, Joe implies that "ease his pain" was about Ray himself. Joe then disappears into the corn.

Ray introduces John (never calling him "Dad") to Annie and Karin. As he heads towards the corn, Ray asks him if he wants to play a game of catch. They begin to play and Annie happily watches. Meanwhile, hundreds of cars can be seen approaching the baseball field, fulfilling Karin and Mann's prophecy that people will come to watch baseball.

Cast

- Kevin Costner as Ray Kinsella

- Amy Madigan as Annie Kinsella

- James Earl Jones as Terence Mann

- Ray Liotta as Shoeless Joe Jackson

- Burt Lancaster as Archibald "Moonlight" Graham

- Frank Whaley as Archie Graham

- Timothy Busfield as Mark

- Dwier Brown as John Kinsella

- Art LaFleur as Chick Gandil

- Michael Milhoan as Buck Weaver

- Steve Eastin as Eddie Cicotte

- Charles Hoyes as Swede Risberg

- Gaby Hoffmann as Karin Kinsella

- Fern Persons as Annie's mother

- Kelly Coffield Park as Dee

Production

Phil Alden Robinson read Shoeless Joe in 1981 and liked it so much that he brought it to producers Lawrence Gordon and Charles Gordon. Lawrence Gordon worked for 20th Century Fox, part of the time as its president, and repeatedly mentioned that the book should be adapted into a film. The studio, however, always turned down the suggestion because they felt the project was too esoteric and noncommercial. Meanwhile, Robinson went ahead with his script, frequently consulting W. P. Kinsella, the book's author, for advice on the adaptation. Lawrence Gordon left Fox in 1986 and started pitching the adaptation to other studios. Universal Studios accepted the project in 1987 and hired USC coach Rod Dedeaux as baseball advisor. Dedeaux brought along World Series champion and USC alumnus Don Buford to coach the actors.[6]

The film was shot using the novel's title; eventually, an executive decision was made to rename it Field of Dreams. Robinson did not like the idea, saying he loved Shoeless Joe, and that the new title was better suited for one about dreams deferred. Later, Kinsella told Robinson that his originally chosen title for the book had been The Dream Field and that the title Shoeless Joe had been imposed by the publisher.[7]

Casting

Robinson and the producers did not originally consider Kevin Costner for the part of Ray because they did not think that he would want to follow Bull Durham with another baseball film. He, however, did end up reading the script and became interested in the project, stating that he felt it would be "this generation's It's a Wonderful Life". Since Robinson's directing debut In the Mood had been a commercial failure, Costner also said that he would help him with the production. Amy Madigan, a fan of the book, joined the cast as Ray's wife, Annie. In the book, the writer Ray seeks out is real-life author J.D. Salinger. When Salinger threatened the production with a lawsuit if his name was used, Robinson decided to rewrite the character as reclusive Terence Mann. He wrote with James Earl Jones in mind because he thought it would be fun to see Ray trying to kidnap such a big man. Robinson had originally envisioned Shoeless Joe Jackson as being played by an actor in his 40s, someone who would be older than Costner and who could thereby act as a father surrogate. Ray Liotta did not fit that criterion, but Robinson thought he would be a better fit for the part because he had the "sense of danger" and ambiguity which Robinson wanted in the character. Burt Lancaster had originally turned down the part of Moonlight Graham, but changed his mind after a friend, who was also a baseball fan, told him that he had to work on the film.[6]

Filming

Filming began on May 25, 1988. The shooting schedule was built around Costner's availability because he would be leaving in August to film Revenge. Except for some weather delays and other time constraints, production rolled six days a week. The interior scenes were the first ones shot because the cornfield planted by the filmmakers was taking too long to grow. Irrigation had to be used to quickly grow the corn to Costner's height. Primary shot locations were in Dubuque County, Iowa; a farm near Dyersville was used for the Kinsella home; an empty warehouse in Dubuque was used to build various interior sets. Galena, Illinois served as Moonlight Graham's Chisholm, Minnesota.[6] One week was spent on location shots in Boston, most notably Fenway Park.[8]

Robinson, despite having a sufficient budget as well as the cast and crew he wanted, constantly felt tense and depressed during filming. He felt that he was under too much pressure to create an outstanding film, and that he was not doing justice to the original novel. Lawrence Gordon convinced him that the end product would be effective.[6]

During a lunch with the Iowa Chamber of Commerce, Robinson broached his idea of a final scene in which headlights could be seen for miles along the horizon. The Chamber folks replied that it could be done and the shooting of the final scene became a community event. The film crew was hidden on the farm to make sure the aerial shots did not reveal them. Dyersville was then blacked out and local extras drove their vehicles to the field. In order to give the illusion of movement, the drivers were instructed to continuously switch between their low and high beams.

Field

Scenes of the Kinsella farm were taken on the property of Don Lansing; some of the baseball field scenes were shot on the neighboring farm of Al Ameskamp. Because the shooting schedule was too short for grass to naturally grow, the experts on sod laying responsible for Dodger Stadium and the Rose Bowl were hired to create the baseball field. Part of the process involved painting the turf green.[6]

After shooting, Ameskamp again grew corn on his property; Lansing maintained his as a tourist destination.[6] He did not charge for admission or parking, deriving revenue solely from the souvenir shop. By the film's twentieth anniversary, approximately 65,000 people visited annually.[9] In July, 2010, the farm containing the "Field" was listed as for sale.[10] It was sold on October 31, 2011, to Go The Distance Baseball, LLC, for an undisclosed fee, believed to be around $5.4 million.[11]

Music

At first, James Horner was unsure if he could work on the film due to scheduling restrictions. Then he watched a rough cut and was so moved that he accepted the job of scoring it. Robinson had created a temp track which was disliked by Universal executives. When the announcement of Horner as composer was made, they felt more positive because they expected a big orchestral score, similar to Horner's work for An American Tail. Horner, in contrast, liked the temporary score, finding it "quiet and kind of ghostly." He decided to follow the idea of the temp track, creating an atmospheric soundtrack which would "focus on the emotions".[6] In addition to Horner's score, portions of several pop songs are heard during the film. They are listed in the following order in the closing credits:

- "Crazy", written by Willie Nelson and performed by Beverly D'Angelo

- "Daydream", written by John Sebastian and performed by The Lovin' Spoonful

- "Jessica", written by Dickey Betts and performed by The Allman Brothers Band

- "China Grove", written by Tom Johnston and performed by The Doobie Brothers

- "Lotus Blossom", written by Billy Strayhorn and performed by Duke Ellington

Historical connections

The character played by Burt Lancaster and Frank Whaley, Archibald "Moonlight" Graham, is based on an actual baseball player with the same name. His character is largely true to life except for a few factual liberties taken for artistic reasons. For instance, the real Graham's lone major league game occurred in June 1905,[12] rather than on the final day of the 1922 season. The real Graham died in 1965, as opposed to 1972 as the film depicts. In the film, Terence Mann interviews a number of people about Graham. The DVD special points out that the facts they gave him were taken from articles written about the real man.

Release and reception

Universal scheduled the film to open in the U.S. on April 21, 1989. It debuted in just a few theaters and was gradually released to more screens so that it would have a spot among the summer blockbusters. It ended up playing until December.[6]

As of June 2017, review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes rates the film 86%, based on 58 reviews with an average score of 7.8/10. The consensus states: "Field of Dreams is sentimental, but in the best way; it's a mix of fairy tale, baseball, and family togetherness."[13] Roger Ebert awarded the film a perfect four stars, admiring its ambition: "This is the kind of movie Frank Capra might have directed, and James Stewart might have starred in—a movie about dreams."[14]

Honors

In June 2008, after having polled over 1,500 people in the creative community, AFI revealed its "Ten Top Ten" — the best ten films in ten "classic" American film genres. The film was acknowledged as the sixth best one in the fantasy genre.[15][16]

- American Film Institute Lists

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies—nominated[17]

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Movie Quotes:

- "If you build it, he will come."—#39

- AFI's 100 Years of Film Scores—nominated[18]

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Cheers—#28

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition)—nominated[19]

- AFI's 10 Top 10—#6 Fantasy Film

In 2017, the US Library of Congress selected Field of Dreams as one of its 25 annual additions to the National Film Registry. The announcement quotes film critic Leonard Maltin, who called the film "a story of redemption and faith, in the tradition of the best Hollywood fantasies with moments of pure magic."[5]

See also

References

- ↑ "Field of Dreams (1989)". IMDb. Retrieved March 19, 2015.

- ↑ Laff at the Movies (April 20, 2012). "Review: "Touchback" Is an Inspiring Drama that Will Make You Smile". Grand Rapids, MI: WOOD-TV. Retrieved August 26, 2013.

- ↑ "'Field of Dreams'". JeffCarneyFilms.com. Retrieved August 26, 2013.

- ↑ "Box Office Information for 'Field of Dreams'". Box Office Mojo. August 26, 2013.

- 1 2 "2017 National Film Registry Is More Than a 'Field of Dreams'" (Press release). Library of Congress. December 13, 2017. Retrieved July 2, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "The 'Field of Dreams' Scrapbook". Field of Dreams (DVD).

- ↑ Easton, Nina J. (April 21, 1989). "Diamonds Are Forever : Director Fields the Lost Hopes of Adolescence". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved March 19, 2015.

- ↑ "Production Notes". Field of Dreams (DVD).

- ↑ King, Susan (December 15, 2009). "'Field of Dreams' Screens to Mark 20th Anniversary". Los Angeles Times.

- ↑ Grossfeld, Stan (July 20, 2010). "Living in a Dream World?". The Boston Globe. Retrieved July 20, 2010.

- ↑ Wilson, Greg (October 31, 2011). "'Field of Dreams' Iowa Farm Sold for Millions". Chicago: WMAQ-TV. Retrieved August 1, 2012.

- ↑ "Moonlight Graham". Retrosheet.org. Retrieved June 5, 2010.

- ↑ "'Field of Dreams'". Rotten Tomatoes.

- ↑ Roger Ebert (April 21, 1989). "Field of Dreams Movie Review & Film Summary (1989)". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved July 17, 2018.

- ↑ "AFI Crowns Top 10 Films in 10 Classic Genres" (Press release). American Film Institute. June 17, 2008. Retrieved June 18, 2008 – via ComingSoon.net.

- ↑ "Top 10 Fantasy". American Film Institute. Archived from the original on June 19, 2008. Retrieved June 18, 2008.

- ↑ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies Nominees" (PDF). American Film Institute. Retrieved March 19, 2015.

- ↑ "AFI's 100 Years of Film Scores: Honoring America's Greatest Film Music" (PDF) (Official ballot). American Film Institute. Retrieved March 19, 2015.

- ↑ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies" (PDF) (Official ballot) (10th Anniversary ed.). American Film Institute. Retrieved March 19, 2015.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Field of Dreams |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Field of Dreams. |