War of the First Coalition

| War of the First Coalition | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the French Revolutionary Wars and the Coalition Wars | |||||||

The Battle of Valmy was a decisive victory for the French revolutionary army | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

First Coalition:

|

French satellites and subdued former enemies:

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| |||||||

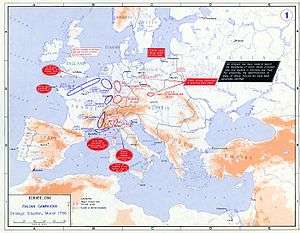

The War of the First Coalition (French: Guerre de la Première Coalition) is the traditional name of the wars that several European powers fought between 1792 and 1797 against the French First Republic.[9] Despite the collective strength of these nations compared with France, they were not really allied and fought without much apparent coordination or agreement. Each power had its eye on a different part of France it wanted to appropriate after a French defeat, which never occurred.[10]

France declared war on the Habsburg Monarchy (cf. the Holy Roman Empire, Austrian Empire etc.) on 20 April 1792. In July 1792, an army under the Duke of Brunswick and composed mostly of Prussians joined the Austrian side and invaded France, only to be rebuffed at the Battle of Valmy in September.

Subsequently these powers made several invasions of France by land and sea, with Prussia and Austria attacking from the Austrian Netherlands and the Rhine, and the Kingdom of Great Britain supporting revolts in provincial France and laying siege to Toulon in October 1793. France suffered reverses (Battle of Neerwinden, 18 March 1793) and internal strife (War in the Vendée) and responded with draconian measures. The Committee of Public Safety formed (6 April 1793) and the levée en masse drafted all potential soldiers aged 18 to 25 (August 1793). The new French armies counterattacked, repelled the invaders, and advanced beyond France.

The French established the Batavian Republic as a sister republic (May 1795) and gained Prussian recognition of French control of the Left Bank of the Rhine by the first Peace of Basel. With the Treaty of Campo Formio, the Holy Roman Empire ceded the Austrian Netherlands to France and Northern Italy was turned into several French sister republics. Spain made a separate peace accord with France (Second Treaty of Basel) and the French Directory carried out plans to conquer more of the Holy Roman Empire (German States, and Austria under the same rule).

North of the Alps, Archduke Charles, Duke of Teschen redressed the situation in 1796, but Napoleon carried all before him against Sardinia and Austria in northern Italy (1796–1797) near the Po Valley, culminating in the Treaty of Leoben and the Treaty of Campo Formio (October 1797). The First Coalition collapsed, leaving only Britain in the field fighting against France.

Background

Revolution in France

As early as 1791, other monarchies in Europe were watching the developments in France with alarm, and considered intervening, either in support of Louis XVI or to take advantage of the chaos in France. The key figure, the Holy Roman Emperor Leopold II, brother of the French Queen Marie Antoinette, had initially looked on the Revolution calmly. He became increasingly concerned as the Revolution grew more radical, although he still hoped to avoid war.

On 27 August 1791, Leopold and King Frederick William II of Prussia, in consultation with émigré French nobles, issued the Declaration of Pillnitz, which declared the concern of the monarchs of Europe for the well-being of Louis and his family, and threatened vague but severe consequences if anything should befall them. Although Leopold saw the Pillnitz Declaration as a way of taking action that would enable him to avoid actually doing anything about France, at least for the moment, Paris saw the Declaration as a serious threat and the revolutionary leaders denounced it.[11]

In addition to the ideological differences between France and the monarchical powers of Europe, disputes continued over the status of Imperial estates in Alsace,[11] and the French authorities became concerned about the agitation of émigré nobles abroad, especially in the Austrian Netherlands and in the minor states of Germany. In the end, France declared war on Austria first, with the Assembly voting for war on 20 April 1792, after the presentation of a long list of grievances by the newly appointed foreign minister Charles François Dumouriez.[12]

1792

Dumouriez prepared an invasion of the Austrian Netherlands, where he expected the local population to rise against Austrian rule. However, the revolution had thoroughly disorganized the French army, which had insufficient forces for the invasion. Its soldiers fled at the first sign of battle, deserting en masse, in one case murdering General Théobald Dillon.[12]

While the revolutionary government frantically raised fresh troops and reorganized its armies, an allied army under Charles William Ferdinand, Duke of Brunswick assembled at Koblenz on the Rhine. The invasion commenced in July 1792. Brunswick's army, composed mostly of Prussian veterans, took the fortresses of Longwy and Verdun.[13] The Duke then issued a declaration on 25 July 1792, which had been written by the brothers of Louis XVI, that declared his [Brunswick's] intent to restore the French King to his full powers, and to treat any person or town who opposed him as rebels to be condemned to death by martial law.[12] This motivated the revolutionary army and government to oppose the Prussian invaders by any means necessary,[12] and led almost immediately to the overthrow of the King by a crowd which stormed the Tuileries Palace.[14]

The invaders continued on, but at the Battle of Valmy on 20 September 1792 they came to a stalemate against Dumouriez and Kellermann in which the highly professional French artillery distinguished itself. Although the battle was a tactical draw, it bought time for the revolutionaries and gave a great boost to French morale. Furthermore, the Prussians, facing a campaign longer and more costly than predicted, decided against the cost and risk of continued fighting, and determined to retreat from France to preserve their army.[9]

Meanwhile, the French had been successful on several other fronts, occupying Savoy and Nice in Italy, while General Custine invaded Germany, capturing Speyer, Worms and Mainz along the Rhine, and reaching as far as Frankfurt. Dumouriez went on the offensive in Belgium once again, winning a great victory over the Austrians at Jemappes on 6 November 1792, and occupying the entire country by the beginning of winter.[9]

1793

On 21 January the revolutionary government executed Louis XVI after a trial.[15] This united all European governments, including Spain, Naples, and the Netherlands against the Revolution. France declared war against Britain and the Netherlands on 1 February 1793 and soon afterwards against Spain. In the course of the year 1793 the Holy Roman Empire (on 23 March), the kings of Portugal and Naples, and the Grand-Duke of Tuscany declared war against France. Thus the First Coalition was formed.[9]

France introduced a new levy of hundreds of thousands of men, beginning a French policy of using mass conscription to deploy more of its manpower than the other states could,[9] and remaining on the offensive so that these mass armies could commandeer war material from the territory of their enemies. The French government sent Citizen Genet to the United States to encourage them into entering the war on France's side. The newly formed nation refused and remained neutral throughout the conflict.

After a victory in the Battle of Neerwinden in March, the Austrians suffered twin defeats at the battles of Wattignies and Wissembourg.[16] British land forces were defeated at the Battle of Hondschoote in September.[16]

1794

1794 brought increased success to the revolutionary armies. A major victory against combined coalition forces at the Battle of Fleurus gained all of Belgium and the Rhineland for France.[16] Although the British navy maintained its supremacy at sea, it was unable to support effectively any land operations after the fall of the Belgian provinces.[17] The Prussians were slowly driven out of the eastern departments[16] and by the end of the year they had retired from any active part in the war.[17] Against Spain, the French made successful incursions in both Catalonia and Navarre.[17]

Action extended into the French colonies in the West Indies. A British fleet successfully captured Martinique, St. Lucia, and Guadeloupe, although a French fleet arrived later in the year and recovered the latter.[18]

1795

After seizing the Low Countries in a surprise winter attack, France established the Batavian Republic as a puppet state. Even before the close of 1794 the king of Prussia retired from any active part in the war, and on 5 April 1795 he concluded with France the Peace of Basel, which recognized France's occupation of the left bank of the Rhine. The new French-dominated Dutch government bought peace by surrendering Dutch territory to the south of that river. A treaty of peace between France and Spain followed in July. The grand duke of Tuscany had been admitted to terms in February. The coalition thus fell into ruin and France proper would be free from invasion for many years.[19]

Britain attempted to reinforce the rebels in the Vendée by landing French Royalist troops at Quiberon, but failed,[20] and attempts to overthrow the government at Paris by force were foiled by the military garrison led by Napoleon Bonaparte, leading to the establishment of the Directory.[21][22]

On the Rhine frontier, General Pichegru, negotiating with the exiled Royalists, betrayed his army and forced the evacuation of Mannheim and the failure of the siege of Mainz by Jourdan.[23]

1796

The French prepared a great advance on three fronts, with Jourdan and Jean Victor Marie Moreau on the Rhine and the newly promoted Napoleon Bonaparte in Italy. The three armies were to link up in Tyrol and march on Vienna.

In the Rhine Campaign of 1796, Jourdan and Moreau crossed the Rhine River and advanced into Germany. Jourdan advanced as far as Amberg in late August while Moreau reached Bavaria and the edge of Tyrol by September. However Jourdan was defeated by Archduke Charles, Duke of Teschen and both armies were forced to retreat back across the Rhine.[23][24]

Napoleon, on the other hand, was successful in a daring invasion of Italy. In the Montenotte Campaign, he separated the armies of Sardinia and Austria, defeating each one in turn, and then forced a peace on Sardinia. Following this, his army captured Milan and started the Siege of Mantua. Bonaparte defeated successive Austrian armies sent against him under Johann Peter Beaulieu, Dagobert Sigmund von Wurmser and József Alvinczi while continuing the siege.[24][23]

The rebellion in the Vendée was also crushed in 1796 by Louis Lazare Hoche.[24] Hoche's subsequent attempt to land a large invasion force in Munster to aid the United Irishmen was unsuccessful.[18]

1797

On 2 February Napoleon finally captured Mantua,[25] with the Austrians surrendering 18,000 men. Archduke Charles of Austria was unable to stop Napoleon from invading the Tyrol, and the Austrian government sued for peace in April. At the same time there was a new French invasion of Germany under Moreau and Hoche.[25]

On 22 February, a French invasion force consisting of 1,400 troops from the La Legion Noire (The Black Legion) under the command of Irish American Colonel William Tate landed near Fishguard in Wales. They were met by a quickly assembled group of around 500 British reservists, militia and sailors under the command of John Campbell, 1st Baron Cawdor. After brief clashes with the local civilian population and Lord Cawdor's forces on 23 February, Tate was forced into an unconditional surrender by 24 February. This would be the only battle fought on British soil during the Revolutionary Wars.

Austria signed the Treaty of Campo Formio in October,[25] ceding Belgium to France and recognizing French control of the Rhineland and much of Italy.[24] The ancient Republic of Venice was partitioned between Austria and France. This ended the War of the First Coalition, although Great Britain and France remained at war.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Nominally the Holy Roman Empire, of which the Austrian Netherlands and the Duchy of Milan were under direct Austrian rule. Also encompassed many other Italian states, as well as other House of Habsburg states such as the Grand Duchy of Tuscany and Liechtenstein

- ↑ Left the war after signing the Peace of Basel with France.

- ↑ Left the war after signing the Peace of Basel with France.

- ↑ Left the war after signing the Treaty of Paris with France.

- ↑ Virtually all of the Italian states, including the neutral Papal States and the Republic of Venice, were conquered following Napoleon's invasion in 1796 and became French satellite states.

- ↑ Re-entered the war as an ally of France after signing the Second Treaty of San Ildefonso.

- ↑ The French Revolutionary Army overthrew the Dutch Republic and established the Batavian Republic as a puppet state in its place.

- ↑ Formed in French-allied Italy in 1797, following the abolition of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth after the Third Partition in 1795.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Holland 1911, Battle of Valmy.

- ↑ (in Dutch) Noah Shusterman – De Franse Revolutie (The French Revolution). Veen Media, Amsterdam, 2015. (Translation of: The French Revolution. Faith, Desire, and Politics. Routledge, London/New York, 2014.) Chapter 7 (p. 271–312) : The federalist revolts, the Vendée and the beginning of the Terror (summer–fall 1793).

- 1 2 Holland 1911, The king and the nonjurors.

- 1 2 3 4 Holland 1911, War declared against Austria.

- ↑ Holland 1911, The revolutionary Commune of Paris.

- ↑ Holland 1911, Rising of the 10th of August.

- ↑ Holland 1911, Trial and execution of Louis XVI.

- 1 2 3 4 Holland 1911, The Revolutionary War. Republican successes..

- 1 2 3 Holland 1911, Progress of the war..

- 1 2 Hannay 1911, p. 204.

- ↑ One of more of the preceding sentences text from a publication now in the public domain: Holland 1911, Progress of the war

- ↑ Holland 1911, Progress of the war.

- ↑ Holland 1911, Insurrection of 13 Vendémiaire.

- ↑ Holland 1911, Character of the Directory.

- 1 2 3 Hannay 1911, p. 182.

- 1 2 3 4 Holland 1911, Military triumphs under the Directory. Bonaparte.

- 1 2 3 Hannay 1911, p. 193.

References

Further reading

- Fremont-Barnes, Gregory. The French Revolutionary Wars (2013)

- Gardiner, Robert. Fleet Battle And Blockade: The French Revolutionary War 1793–1797 (2006)

- Lefebvre, Georges. The French Revolution Volume II: from 1793 to 1799 (1964).

- Ross, Steven T. Quest for Victory; French Military Strategy, 1792–1799 (1973)

External links