Rhine Campaign of 1795

| Rhine Campaign of 1795 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of War of the First Coalition | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 175,000 | 187,000 | ||||||

In the Rhine Campaign of 1795 (April 1795 to January 1796), two Habsburg Austrian armies under the overall command of François Sébastien Charles Joseph de Croix, Count of Clerfayt, defeated two Republican French armies to invade the south German states of the Holy Roman Empire. At the start of the campaign, the French Army of the Sambre and Meuse, led by Jean-Baptiste Jourdan, confronted Clerfayt's Army of the Lower Rhine in the north, while the French Army of the Rhine and Moselle, under Jean-Charles Pichegru, lay opposite Dagobert Sigmund von Wurmser's Army of the Upper Rhine in the south. An early summer offensive failed. In August, Jourdan crossed the Rhine and quickly seized Düsseldorf. The Army of the Sambre and Meuse advanced south to the Main River, completely isolating Mainz. Pichegru's army made a surprise capture of Mannheim; subsequently, both French armies held significant footholds on the east bank of the Rhine.

The French fumbled the promising start to their offensive when Pichegru bungled an opportunity to seize Clerfayt's supply base in the Battle of Handschuhsheim. While Pichegru delayed, Clerfayt massed against Jourdan, beat him at Höchst in October and forced most of the Army of the Sambre and Meuse to retreat to the west bank of the Rhine. At about the same time, Wurmser sealed off the French bridgehead at Mannheim. With Jourdan temporarily out of the picture, the Austrians defeated the left wing of the Army of the Rhine and Moselle at the Battle of Mainz and moved down the west bank. In November, Clerfayt gave Pichegru a drubbing at Pfeddersheim and successfully wrapped up the Siege of Mannheim. In January 1796, Clerfayt concluded an armistice with the French, allowing the Austrians to retain large portions of the west bank. During the campaign Pichegru entered into traitorous contact with French Royalists. It is debatable whether Pichegru's treason, his bad generalship, or the unrealistic expectations of the war planners in Paris was the actual cause of the French failure.

Background

The rulers of Europe initially viewed the French Revolution as an internal dispute between the French king Louis XVI and his subjects. As revolutionary rhetoric grew more strident, the monarchs of Europe declared their interests as one with those of Louis and his family. The Declaration of Pillnitz (27 August 1791) threatened ambiguous, but quite serious, consequences if anything should happen to the French royal family. French émigrés, who had the support of the Habsburgs, the Prussians, and the British, continued to agitate for a counter-revolution.[1] On 20 April 1792, the French National Convention declared war on the Habsburg Monarchy, pushing Great Britain, the Kingdom of Portugal, the Ottoman Empire and the Holy Roman Empire into the War of the First Coalition (1792–98).[1]

From 1793 to 1794, French success varied. By 1794, the armies of the French Republic were in a state of disruption. The most radical of the revolutionaries purged the military of all men conceivably loyal to the Ancien Régime (Old Regime). The levée en masse (mass conscription) created a new kind of army with thousands of illiterate, untrained men placed under the command of officers whose principal qualifications may have been their loyalty to the Revolution instead their military acumen.[2] Traditional military organization was disrupted by the formation of the new demi-brigades, units created by the amalgamation of old military units with new revolutionary formations: each demi-brigade included one unit of the old royal army and two created from the mass conscription. The losses of this revolutionized army early in the Rhine Campaign of 1795 disappointed the French public and the French government.[1]

In addition, by early 1795, the army had made itself odious throughout France, by both rumor and action, through its rapacious dependence upon the countryside for material support and its general lawlessness and undisciplined behavior. The French Directory believed that war should pay for itself and did not budget to pay, feed, or equip its troops.[3] Thus, a campaign that would take the army out of France became increasingly urgent for both budgetary and internal security reasons.[1]

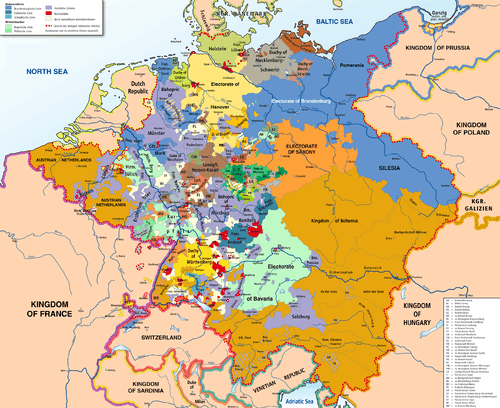

Political terrain

The predominantly German-speaking states on the east bank of the Rhine were part of the vast complex of territories in central Europe called the Holy Roman Empire, of which the Archduchy of Austria was a principal polity; its archduke was typically the Holy Roman Emperor. The French government considered the Holy Roman Empire as its principal continental enemy.[4] The territories of the Empire in 1795 included more than 1,000 entities, including Breisgau (Habsburg), Offenburg and Rottweil (free cities), the territories belonging to the princely families of Fürstenberg and Hohenzollern, the duchies of Baden and Württemberg plus several dozen ecclesiastic polities. Much of the territory of these polities was not contiguous: a village could belong predominantly to one polity, but have a farmstead, a house, or even one or two strips of land that belonged to another polity. The size and influence of the polities varied, from the Kleinstaaterei, the little states that covered no more than a few square miles, or included several non-contiguous pieces, to such sizable territories as Bavaria and Prussia.[5]

The governance of these states also varied: they included the autonomous free Imperial cities (also of different sizes and influence), ecclesiastical territories, and dynastic states such as Prussia. Through the organization of Imperial Circles, also called Reichskreise, groups of states consolidated resources and promoted regional and organizational interests, including economic cooperation and military protection. Without the participation of such principal states of the Empire as the Archduchy of Austria, Prussia, the Electorate of Saxony, and Bavaria, for example, these small states were vulnerable to invasion and conquest because they were unable to defend themselves on their own. Consequently, in times of immediate threat, they all contributed to the Imperial Army, which was composed of professional units of the Austrian empire, usually recruited from the Balkan states and experienced through the years of warfare with the Ottoman Empire. Additional professional units came from some of the larger polities of the empire, including the duchies of Saxony, Württemberg, and Bavaria.[5][Note 1]

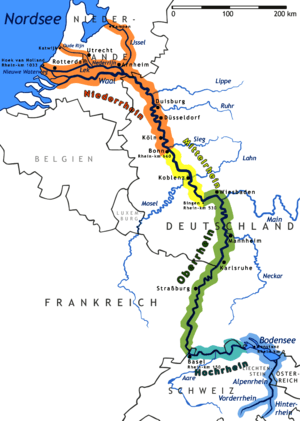

Geography

The Rhine formed the boundary between the German states of the Holy Roman Empire and its neighbors, principally France, but also Switzerland and the Netherlands. Any attack by either party required control of the crossings.[Note 2] At Basel, where the river makes a wide, northerly turn at the Rhine knee, it enters what the locals call the Rhine Ditch (Rheingraben). This forms part of a rift valley some 31 km (19 mi) wide bordered by the mountainous Black Forest on the east (German side) and the Vosges mountains on the west (French side). At the far edges of the eastern flood plain, tributaries cut deep defiles into the western slope of the mountains.[7] Further to the north, the river became deeper and faster, until it widened into a delta where it emptied into the North Sea.[8] In the 1790s, the river was wild and unpredictable and armies crossed at their peril. Between the Rhine knee and Mannheim, channels wound through marsh and meadow, and created islands of trees and vegetation that were periodically submerged by floods. Flash floods originating in the mountains could submerge farms and fields. Any army wishing to traverse the river had to cross at specific points: in 1790, systems of viaducts and causeways made access across the river reliable, but only at Kehl, by Strasburg, at Hüningen, by Basel, and in the north by Mannheim. Sometimes, crossing could be executed at Neuf-Brisach, between Kehl and Hüningen, but the small bridgehead made this unreliable.[9][Note 3] Only to the north of Kaiserslauten did the river acquire a defined bank where fortified bridges offered reliable crossing points.[11]

Plans for 1795

By 1794-95, military planners in Paris considered the upper Rhine Valley, the south-western German territories and the Danube river basin of strategic importance for the defense of the Republic. The Rhine offered a formidable barrier to what the French perceived as Austrian aggression, and the state that controlled its crossings controlled the river and access into the territories on either side. Ready access across the Rhine and along the Rhine bank between the German states and Switzerland or through the Black Forest, gave access to the upper Danube river valley. For the French, control of the Upper Danube would give the them a reliable approach to Vienna.[12]

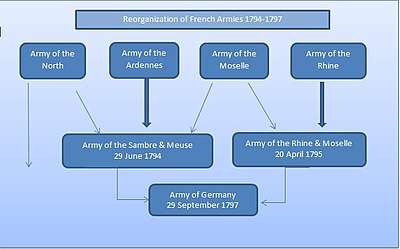

Parisian revolutionaries and military commanders alike believed that an assault into the German states was essential, not only in terms of war aims but also in practical terms: the French Directory believed that war should pay for itself and did not budget for the payment or feeding of its troops.[13] Theirs was an army entirely dependent for support upon the countryside it occupied. The planners reorganized the army into task forces. The right flank of the Armies of the Center, later the called the Army of the Moselle, the entire Army of the North and the Army of the Ardennes were combined to form the Army of the Sambre and Meuse. The remaining units of the former Army of the Center and the Army of the Rhine were united, initially on 29 November 1794, and formally on 20 April 1795, under the command of Jean-Charles Pichegru. Although this solved some of the problems of feeding and paying the army, it did not solve them all. Until April 1796, soldiers were paid in an increasingly worthless paper currency called the Assignat; after April, pay was made in metallic currency, but still in arrears. Throughout the spring and early summer, the soldiers were in almost constant mutiny: in May 1796, in the border town of Zweibrücken, a demi-brigade revolted. In June, pay for two demi-brigades was in arrears and two companies rebelled.[3]

Campaign of 1795

The Rhine Campaign of 1795 (April 1795 to January 1796) opened when two Habsburg armies under the overall command of François Sébastien Charles Joseph de Croix, Count of Clerfayt confronted an attempt by two Republican French armies to cross the Rhine River and capture the Fortress of Mainz. The French Army of the Sambre and Meuse, commanded by Jean-Baptiste Jourdan, confronted Clerfayt's Army of the Lower Rhine in the north, while the French Army of Rhine and Moselle under the command of Pichegru lay opposite Dagobert Sigmund von Wurmser's army in the south.[14]

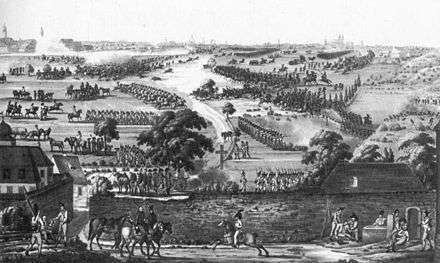

In August, Jourdan crossed and quickly seized Düsseldorf. The Army of the Sambre and Meuse advanced south to the Main River, isolating Mainz. On 20 September 1795, 30,000 French troops under the command of Jourdan laid siege to Mannheim. The Coalition garrison of 9,600 negotiated secretly with the French to relinquish the fortress. The French used Mannheim as a staging area for much of the 1795 campaign.[15] Both French armies held significant footholds on the east bank of the Rhine, but this promising advance into the German states faltered.[14]

Pichegru bungled at least one opportunity to seize Clerfayt's supply base in the Battle of Handschuhsheim. Pichegru had sent two divisions commanded by Dufour to seize the Coalition supply base near Heidelberg but his troops were attacked at Handshuhsheim, a Heidelberg suburb. The Austrian cavalry, under the command of Johann von Klenau, included six squadrons each of the Hohenzollern Cuirassier Regiment Nr. 4 and Szekler Hussar Regiment Nr. 44, four squadrons of the Allemand Dragoon Regiment, an Émigré unit, and three squadrons of the Royal Dragoon Regiment Nr. 3. As Dufour's troops moved through open country, Klenau's horsemen charged them. The Austrians first routed six squadrons of French chasseurs à cheval then turned against the foot soldiers. Dufour's division was cut to pieces; Dufour was captured.[14]

Clerfayt massed his troops against Jourdan, beat him at Höchst in October, and forced most of the Army of the Sambre and Meuse to retreat to the west bank of the Rhine. About the same time, Wurmser sealed off the French bridgehead at Mannheim. With Jourdan temporarily out of the picture, the Austrians defeated the left wing of the Army of the Rhine and Moselle at the Battle of Mainz: 17,000 Coalition troops commanded by Wurmser engaged 12,000 Republican French soldiers, commanded by Pichegru, who were encamped outside the Mannheim fortress. Wurmser drove them from their encampment; they either retreated into the city of Mannheim or joined other forces in the region. Wurmer then laid siege to the French troops who had sought safety inside the city walls.[14] At Mainz, on 29 October 1795, a Coalition army of 27,000, led by Count of Clerfayt, launched a surprise assault against four divisions (33,000) of the French Army of the Rhine and Moselle directed by François Ignace Schaal. The French division on the farthest right flank fled the battlefield, compelling the other three divisions to retreat, with the loss of their siege artillery and many casualties.[15]

On 10 November 1795, Clerfayt gave Pichegru a drubbing at Pfeddersheim. The French continued to withdraw. Clerfayt advanced with 75,000 Coalition troops south along the west bank of the Rhine against Pichegru's 37,000-man strong defenses behind the Pfrimm River near Worms. At Frankenthal (13–14 November 1795), an Austrian victory forced Pichegru to abandon his last defensive position north of Mannheim.[16]

Once the French troops at Pfeddersheim abandoned their position, the French position at Mannheim, invested by the Coalition since October, became untenable. On 22 November 1795, after a one-month siege, the 10,000-strong French garrison, commanded by Anne Charles Basset Montaigu, surrendered. This event brought the 1795 campaign in Germany to an end.[17]

Subsequent plans

In January 1796, Clerfayt concluded an armistice with the French. The Austrians retained large portions of the west bank.[18] Despite the armistice, both sides continued to plan for war. In a decree on 6 January 1796, Lazare Carnot, one of the five French Directors, again gave Germany priority over Italy as a theater of war. The French First Republic's finances were in poor shape, so its armies would be expected to invade new territories and then live off the conquered lands, as they had been instructed to do in 1795.[19]Knowing that the French planned to invade Germany, on 20 May 1796 the Austrians announced that the truce would end on 31 May, and prepared for invasion.[20]

Of the lessons learned in both 1794 and 1795, the Habsburgs may have concluded that they could not rely on their allies. For example, in its prompt capitulation of Mannheim, the Bavarian garrison had surrendered all supplies, horses, armaments, and weaponry, an action that further confirmed to the Habsburg commanders that their allies were not reliable. By 1795, they were better prepared to make war alone, placing Wurmser and Clerfayt, both experienced commanders, in charge of their own forces. After 1795, they had clearly learned more lessons. Consolidating forces where possible along the Rhine, the Habsburg military prepared for 1796 by mobilizing the imperial contingents into their own army: this meant drafting raw recruits from the ten "Circles," and providing basic training for them in the time available. They placed Archduke Charles, Duke of Teschen, the emperor's brother and arguably the best of the Habsburg generals, in command. Charles was authorized to act as he saw fit.[21] Even with his augmented force, however, in the spring of 1796, Charles had half the number of troops covering a 340-kilometer (211 mi) front that stretched from Switzerland to the North Sea in what Gunther Rothenberg called the "thin white line".[Note 4] Imperial troops could not cover the territory from Basel to Frankfurt with sufficient depth to resist the pressure of their opponents.[22]

School for Marshals

Historians generally accept the French results of the Campaign of 1795 as an unmitigated disaster. The poor showing of the French may have been linked to Pichegru's treachery. By 1795, Pichegru was leaning heavily toward the Royalist cause. During the campaign, he accepted money from a British agent and was in contact with persons who wished for a return of the French monarchy. Despite reason for suspicion, he was left in command of the Army of the Rhine and Moselle until March 1796, when he resigned. He returned to Paris, where he was greeted with great acclaim by the populace. His replacement in army command was General of Division Jean Victor Marie Moreau.[23]

Historians still debate whether Pichegru's treason, his bad generalship, or the unrealistic expectations set by the military planners in Paris were the actual cause of the French failure. Regardless, Ramsey Weston Phipps maintained

To any one who believes with me that it is good to study bad as well as skilful [sic] campaigns and plans, the operations of 1795 are most interesting; for, while the actions of Jourdan, as far as he had a free hand, were sensible enough, those of Pichegru were like the nightmare of a professor of strategy, and the plans of the Comité degenerated into sheer farce.[24]

In the campaigns of 1795 and 1796, a cadre of young officers acquired valuable experience for future campaigns. Phipps emphasized the importance of experience under these trying conditions of manpower shortage, poor training, equipment and supply shortage, and tactical and strategic confusion and interference in his five volume analysis of the Revolutionary Armies. The training received in the early years of the war varied not only with the theater in which the young officers served but also with the character of the army to which they belonged.[25] The experience of young officers under the tutelage of such experienced men as Pichegru, Moreau, Lazar Hoche, Lefebvre, and Jourdan provided young officers with valuable lessons of what to do and what not to do.[26]

Phipps' analysis was not singular, although his lengthy volumes addressed in detail the value of this so-called "school for marshals". In 1895, Richard Dunn Pattison also singled out the French Revolutionary War Rhine campaigns as "the finest school the world has yet seen for an apprenticeship in the trade of arms".[27] In 1795, Pichegru remained inactive for the better part of August, subsequently losing any opportunity to acquire the Habsburg supply depot outside Heidelberg. Phipps speculated on why Moreau gained renown by the supposed skill of his 1796 retreat and suggested that it was not skillful for Moreau to allow the inferior columns of Latour, Nauendorf and Fröhlich to herd him back to France. Even during his advance, Phipps maintained, Moreau was irresolute and Jourdan seemed to have an unwarranted faith in Pichegru's abilities and resolve.[28] Jean-de-Dieu Soult, who participated in the campaign as an infantry brigadier, noted that Jourdan too made many errors but the French government's errors were worse. The French were unable to pay for supplies because their currency was worthless, so the soldiers stole everything. This ruined discipline and turned the local populations against the French.[29]

Emperor Napoleon I also recognized this when he resurrected of the ancien regime civil dignity of the marchalate to strengthen his power. He could reward the most valuable of his generals or soldiers who had held significant commands during the French Revolutionary Wars.[30] The Army of the Rhine and Moselle (and its subsequent incarnations) included five future Marshals of France: Jean-Baptiste Jourdan, its commander-in-chief, Jean-Baptiste Drouet, Laurent de Gouvion Saint-Cyr, and Édouard Adolphe Casimir Joseph Mortier.[31] François Joseph Lefebvre, by 1804 an old man, was named an honorary marshal, but not awarded a field position. Michel Ney, in the 1795–1799 campaigns an intrepid cavalry commander, came into his own command under the tutelage of Moreau and Massena in the south German and Swiss campaigns. Jean de Dieu Soult had served under Moreau and Massena, becoming the latter's right-hand man during the Swiss campaign of 1799–1800. Jean Baptiste Bessieres, like Ney, was a competent and sometimes inspired regimental commander in 1796. MacDonald, Oudinot and Saint-Cyr, participants in the 1796 campaign, all received honors in the third, fourth and fifth promotions (1809, 1811, 1812).[30]

Notes, citations and sources

Notes

- ↑ Beginning in the sixteenth century, the Holy Roman Empire was organized loosely into ten "circles" (Kreise) or regional groups of ecclesiastical, dynastic and secular polities that coordinated economic, military and political actions. During times of war, the Circles contributed troops to the Habsburg military by drafting (or soliciting volunteers) among their inhabitants. Some circles coordinated their efforts better than others; the Swabian Circle was among the more effective of the Imperial circles at organizing itself and protecting its economic interests. This structure is explained in more detail in James Allen Vann, The Swabian Kreis: Institutional Growth in the Holy Roman Empire 1648–1715. Vol. LII, Studies Presented to International Commission for the History of Representative and Parliamentary Institutions. Bruxelles, 1975 and Mack Walker, German Home Towns: Community, State, and General Estate, 1648–1871. Ithaca, Cornell, 1998.

- ↑ The river began in the Swiss canton of Graubünden (also called the Grisons) near Lake Toma and flowed along the Alpine region bordered by Liechtenstein, northward into Lake Constance. The river left the lake by Reichenau and flowed westerly; at Stein am Rhein it dropped precipitously 23 meters (75 ft) in an unnavigable waterfall and flowed westerly along the border between the German states and the Swiss cantons. The c. 150-kilometer (93 mi) stretch between Stein am Rhein and Basel, called the High Rhine, cut through steep hillsides only near the Rhine Falls and flowed over a gravel bed; in such places as the former rapids at Laufenburg, or after the confluence with the even larger Aare below Koblenz, Switzerland, it moved in torrents.[6]

- ↑ The Rhine itself looked different in the 1790s than it does in the twenty-first century; in the nineteenth century, the passage from Basel to Iffezheim was "corrected" (straightened) to make year-round transport easier. Between 1927 and 1975, the construction of a canal allowed better control of the water level.[10]

- ↑ Habsburg infantry wore white coats.[22]

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 Timothy Blanning. The French Revolutionary Wars, New York, Oxford University Press, 1998, pp. 41–59.

- ↑ (in French) Roger Dupuy, Nouvelle histoire de la France contemporaine. La République jacobine, Paris, Seuil, 2005, p. 156.

- 1 2 Jean Paul Bertaud, R. R. Palmer (trans). The Army of the French Revolution: From Citizen-Soldiers to Instrument of Power, Princeton University Press, 1988, pp. 283–290; Ramsay Weston Phipps, The Armies of the First French Republic: Volume II: The Armées du Moselle, du Rhin, de Sambre-et-Meuse, de Rhin-et-Moselle, Pickle Partners Publishing, (1932– ), v. II, p. 184; (in French)Charles Clerget, Tableaux des armées françaises: pendant les guerres de la Révolution, [Paris], R. Chapelot, 1905, p. 62; and Digby Smith, Napoleonic Wars Data Book. Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania, Stackpole, 1999, pp. 111, 120.

- ↑ Joachim Whaley, Germany and the Holy Roman Empire: Volume I: Maximilian I to the Peace of Westphalia, 1493–1648, Oxford University Press, 2012, vol.1, pp. 17–20.

- 1 2 Mack Walker, German Home Towns: Community, State, and General Estate, 1648–1871, Cornell University Press, 1998, Chapters 1–3.

- ↑ Thomas P. Knepper, The Rhine. Handbook for Environmental Chemistry Series, Part L, New York, Springer, 2006, pp. 5–19.

- ↑ Knepper, pp. 19–20.

- ↑ (in German) Johann Samuel Ersch, Allgemeine encyclopädie der wissenschaften und künste in alphabetischer folge von genannten schrifts bearbeitet und herausgegeben. Leipzig, J. F. Gleditsch, 1889, pp. 64–66.

- ↑ Thomas Curson Hansard (ed.) .Hansard's Parliamentary Debates, House of Commons, 1803, Official Report. Vol 1, London, HMSO, 1803, pp. 249–252.

- ↑ (in German) Helmut Volk. "Landschaftsgeschichte und Natürlichkeit der Baumarten in der Rheinaue." Waldschutzgebiete Baden-Württemberg, Band 10, 2006, pp. 159–167.

- ↑ David Gates, The Napoleonic Wars 1803–1815, New York, Random House, 2011, Chapter 6.

- ↑ Gunther E. Rothenberg, Napoleon’s Great Adversaries: Archduke Charles and the Austrian Army, 1792–1914, Stroud, (Gloucester): Spellmount, 2007, pp. 70–74.

- ↑ Bertaud, pp. 283–290.

- 1 2 3 4 Ramsay Weston Phipps, The Armies of the First French Republic: Volume II The Armées du Moselle, du Rhin, de Sambre-et-Meuse, de Rhin-et-Moselle, US, Pickle Partners Publishing, 2011 (1923–1933), p. 212.

- 1 2 Digby Smith. Napoleonic Wars Data Book, NY: Greenhill Press, 1996, p. 105.

- ↑ Smith, p. 108.

- ↑ J. Rickard, Combat of Heidelberg, 23–25 September 1795, Mannheim and Heidelberg. 10 February 2009 version, accessed 6 March 2015. Smith, p. 105.

- ↑ Theodore Ayrault Dodge, Warfare in the Age of Napoleon: The Revolutionary Wars Against the First Coalition in Northern Europe and the Italian Campaign, 1789–1797, Leonaur Ltd, 2011, pp. 286–287.

- ↑ David G. Chandler, The Campaigns of Napoleon, Macmillan, 1966, pp. 46–47.

- ↑ Phipps, v. 2, p. 278.

- ↑ Rothenberg, pp. 37-39.

- 1 2 Gunther E. Rothenberg, "The Habsburg Army in the Napoleonic Wars (1792–1815)". Military Affairs, (Feb 1973) 37:1, pp. 1–5.

- ↑ Rothenberg, p. 39

- ↑ Phipps, p. 212.

- ↑ Phipps, vol. 2, p. iii.

- ↑ Frank McLynn, Napoleon: A Biography. nl, Skyhorse Publishing In, 2011, Chapter VIII.

- ↑ Richard Phillipson Dunn-Pattison, Napoleon's marshals., Wakefield, EP Pub., 1977 (reprint of 1895 edition), pp. viii–xix, xvii quoted.

- ↑ Phipps, pp. 347, 400–402.

- ↑ Phipps, pp. 395–396.

- 1 2 Dunn-Pattison, pp. xviii–xix.

- ↑ Phipps, pp. 90–94.

Sources

- Bertaud, Jean Paul, R. R. Palmer (trans). (1988). The Army of the French Revolution: From Citizen-Soldiers to Instrument of Power. US: Princeton University Press. OCLC 17954374.

- Blanning, Timothy (1998). The French Revolutionary Wars. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-340-56911-5.

- Dodge, Theodore Ayrault (2011). Warfare in the Age of Napoleon: The Revolutionary Wars Against the First Coalition in Northern Europe and the Italian Campaign, 1789-1797. USA: Leonaur Ltd. ISBN 978-0-85706-598-8.

- Ersch, Johann Samuel (1889). Allgemeine encyclopädie der wissenschaften und künste in alphabetischer folge von genannten schrifts bearbeitet und herausgeben (in German). Leipzig: J. F. Gleditsch. pp. 64–66. OCLC 978611925.

- Graham, Thomas, 1st Baron Lynedoch. (1797) The History of the Campaign of 1796 in Germany and Italy. London, (np). OCLC 44868000

- Hansard, Thomas C., ed. (1803). Hansard's Parliamentary Debates, House of Commons, 1803, Official Report. I. London: HMSO. OCLC 85790018.

- Knepper, Thomas P. (2006) The Rhine. Handbook for Environmental Chemistry Series, Part L. New York: Springer. ISBN 978-3540293934

- McLynn, Frank. (2002) Napoleon: A Biography. New York, Arcade Pub. OCLC 49351026

- Dunn-Pattison, Richard Phillipson. (1897 reprinted 1977) Napoleon's Marshals, Wakefield, EP Pub. OCLC 3438894

- Phipps, Ramsay Weston (2011). The Armies of the First French Republic: Volume II The Armées du Moselle, du Rhin, de Sambre-et-Meuse, de Rhin-et-Moselle. USA: Pickle Partners Publishing. ISBN 978-1-908692-25-2.

- Rothenberg, Gunther E. (Feb 1973), "The Habsburg Army in the Napoleonic Wars (1792–1815)". Military Affairs, 37:1, pp. 1–5. ISSN 0026-3931

- Rothenberg, Gunther E. (2007). Napoleon's Great Adversaries: Archduke Charles and the Austrian Army, 1792–1914. Gloucester: Spellmount. ISBN 978-1-908692-25-2.

- Smith, Digby (1998). The Napoleonic Wars Data Book. London: Greenhill. ISBN 978-1-85367-276-7.

- Vann, James Allen (1975). The Swabian Kreis: Institutional Growth in the Holy Roman Empire 1648–1715. LII. Brussels: Studies Presented to International Commission for the History of Representative and Parliamentary Institutions. OCLC 923507312.

- Volk, Helmut (2006). "Landschaftsgeschichte und Natürlichkeit der Baumarten in der Rheinaue". Waldschutzgebiete Baden-Württemberg (in German). X: 159–167. OCLC 939802377.

- Walker, Mack (1998). German Home Towns: Community, State and General Estate, 1648–1871. Ithaca, N. Y.: Cornell University Press. OCLC 2276157.

- Whaley, Joachim (2012). Germany and the Holy Roman Empire: Maximilian I to the Peace of Westphalia, 1493–1648. I. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-968882-1.

Web sources

- Rickard, J. (2009). "Combat of Frankenthal, 13-14 November 1795". historyofwar.org. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- Rickard, J. (2009). "Combat of Heidelberg, 23-25 September 1795". historyofwar.org. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- Rickard, J. (2009). "Combat of the Pfrimm, 10 November 1795". historyofwar.org. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- Rickard, J. (2009). "Battle of Höchst, 11 October 1795". historyofwar.org. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- Rickard, J. (2009). "Siege of Mannheim, 10 October-22 November 1795". historyofwar.org. Retrieved 18 August 2014.