Madame Roland

| Marie-Jeanne Phlippon Roland | |

|---|---|

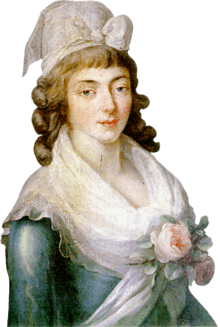

Portrait of Madame Roland | |

| Born |

Marie-Jeanne Phlippon 17 March 1754 Paris, France |

| Died |

8 November 1793 (aged 39) Paris, France |

| Cause of death | Guillotine during Reign of Terror |

| Residence | Lyon, France and Paris, France |

| Nationality | French |

| Other names | Madame Roland |

| Known for | salon, Girondist faction of French revolution, wrote political articles |

| Opponent(s) | Robespierre |

| Spouse(s) | Jean-Marie Roland de la Platière |

| Parent(s) | Gratien Phlippon |

| Signature | |

|

| |

Madame Roland née Marie-Jeanne Phlippon, also known as Jeanne Manon Roland (17 March 1754 – 8 November 1793), was, together with her husband Jean-Marie Roland de la Platière, a supporter of the French Revolution and influential member of the Girondist faction. She fell out of favour during the Reign of Terror and died on the guillotine.

Early years

Madame Roland, born Marie-Jeanne Phlippon, the sole surviving child of eight pregnancies, was born to Gratien Phlippon and Madame Phlippon in March 1754. From her early years she was a successful, enthusiastic, and talented student. In her youth she studied literature, music and drawing. From the beginning she was strong willed and frequently challenged her father and instructors as she progressed through an advanced, well-rounded education.

Enthusiastically supporting her education, Jeanne's parents enrolled her in the convent school of the Sisterhood of the Congregation in Paris - for one year only. She was enthusiastically religious, leading John Abbott to state "God thus became in Jane's mind a vision of poetic beauty".[1] Following her convent school education, she pursued her education independently, Abbott relating that "Heraldry and books of romance, lives of the saints and fairy legends, biography, travels, history, political philosophy, poetry, and treatises upon morals, were all read and meditated upon by this young child".[2] Several literary figures influenced Roland's philosophy, including Voltaire, Montesquieu, Plutarch, and others. Most significantly, Rousseau's literature strongly influenced Roland's understanding of feminine virtue and political philosophy, and she came to understand a woman's genius as residing in Rousseau's definition of feminine virtue as "a pleasurable loss of self-control", which for Roland meant the courage of maternal self-sacrifice and suffering.[3]

Manon Phlippon (as her close friends and relatives called her) also, as she traveled, developed an increasing awareness of the outside world. In 1774, on a trip to Versailles, some of her most famous letters were sent to her friend Sophie Cannet, wherein she first begins to display an interest in politics, describing admiringly (if not presciently) the enthronement of Louis XVI and his queen Marie Antoinette fifteen years before the start of the French Revolution:

The ministers are enlightened and well disposed, the young prince docile and eager for good, the queen amiable and beneficent, the court kind and respectable, the legislative body honourable, the people obedient, wishing only to love their master, the kingdom full of resources. Ah but we are going to be happy![4]

Marriage and political activity

In the winter of 1780, Manon Phlippon married the philosopher Jean-Marie Roland de la Platière. 20 years her senior, M. Roland was politically ambitious, and following their marriage, Madame Roland's love for literature and her husband's political aspirations formed a new foundation for her intellectual development. She collaborated on a number of M. Roland's works: the Dictionnaire des Manufactures, Arts et Métiers, and a contribution to Panckoucke's Encyclopedie Methodique, in particular. Her most significant influence flowed through her husband's political writings. Nevertheless, attempting to conform to Rousseau's model of femininity, she also carefully restricted herself "well within the limits of a woman's domestic function".[5] Thus, with him and through him, she proved both powerful and influential in the era of the French Revolution.[6]

In 1784, she obtained a promotion for her husband which transferred him to Lyon, where she began building her network of friends and associates. In Lyon, the Rolands began to express their political support for the revolution through letters to the journal Patriote Français. Their voice was noticed and in November 1790, Jean-Marie was elected to represent Lyon in Paris, negotiating a loan to reduce the debt of Lyon. When the couple moved from Lyon to Paris in 1791, she began to take an even more active role. Her salon at the Hotel Britannique in Paris became the rendezvous of Brissot, Pétion, Robespierre and other leaders of the popular movement. An especially esteemed guest was Buzot, whom she loved with platonic enthusiasm. These leaders of the Girondist faction of the Jacobin Club met to discuss the rights of citizens and strategies to transform the French from subjects of the Monarchy into citizens of a constitutional republic.

In person, Madame Roland is said to have been attractive but not beautiful; her ideas were clear and far-reaching, her manner calm, and her power of observation extremely acute. Madame Roland’s ability to weave social networks fed the Rolands' growing popularity; an invitation from Madame Roland would signify acknowledged importance to the developing French government. It was through Manon that one gained access to the inner circle of the growing Gironde. Inevitably, her activity placed her in the centre of political aspirations where she swayed a company of the most talented men of progress.

As noted above, Madame Roland began her movement toward political involvement slowly, initially acting as her husband’s secretary, and later developing into a far more influential member of revolutionary politics. As time went on she realised that she could tweak a number of her husband’s letters and still sign them in his name. M. Roland’s rise in politics and the Girondin faction subsequently improved Madame Roland’s influence. In maintenance of her feminist beliefs she never spoke during formal meetings. Instead she listened intently at her desk, taking notes, thus educating herself on political matters.[5] Independently, M. Roland performed sufficiently in his duties as a minister, possessing reasonable knowledge, activity, and integrity. In combination with Madame Roland, he shone due to his ability to articulate writings infused with spirit, gentleness, authoritative reason, and seducing sentiment.[7] Consequently, whenever M. Roland spoke, it was generally known that he was speaking also for her. Girondin policies reflected her sentiments. This political influence continued until the downfall of the Girondin movement, related to Madame Roland's notoriety provoking strong opposition from the Montagnards and celebrated figures such as Robespierre, Danton, and Marat.

As a result of ideological differences, Madame Roland and her husband defected from the Jacobins in early 1792 and, with Jacques-Pierre Brissot, formed the moderate Girondin party. The Girondists desire to bring liberty to the people, whilst simultaneously implementing control coincided with Madame Roland’s political beliefs, thus satisfying her "appetite": "All her tastes were with the ancient nobility and their defenders. All her principles were with the people".[8] Succeeding the surrender of King Louis XVI, the Girondists installed M. Roland as Minister of the Interior. At the time, this position was particularly dangerous, creating an alternate representation of the French monarchy. This "promotion" added to the spirit of Madame Roland, "whose all-absorbing passion it now was to elevate her husband to the highest summits of greatness, was gratified in view of the honor and agitated in view of the peril".[9] During this period, she authored much of his official correspondence, including the letter to the King of 21 June 1792, which urged the King to publicly pledge his loyalty and cooperation to the new republic, or suffer the consequences of escalating civil unrest.[6] Madame Roland’s sharply worded passion cost her husband his ministry, but satisfied Madame Roland’s pride and passion. This letter to the King could be considered the peak of her political influence. After Monsieur Roland made a stand against the worst excesses of the Revolution, however, the couple became unpopular. After Monsieur Roland denounced the September Massacres and voted against the King’s execution in January 1793, Danton blamed his wife publicly for influencing her husband. On 9 September 1792, after the September Massacres (2–7 September 1792) she wrote to François Buzot, " Danton leads the whole thing; Robespierre is his puppet, Marat holds his torch and dagger; this fiery orator rules and we are being oppressed until we fall as his victims.[10] "Once, Madame Roland appeared personally in the Assembly to repel the falsehoods of an accuser, and her ease and dignity evoked enthusiasm and compelled acquittal.[11] Her drive, focus, and radiant intelligence made her the equal in accomplishments of any contemporary male politician.

Nevertheless, the accusations mounted. On 31 May 1793, she, along with other Girondins, was arrested for treason.[6] She was thrown into the prison of the Abbaye. Her husband escaped to Rouen. Released for an hour from the Abbaye, she was again arrested and placed in Sainte-Pelagie, and finally transferred to the Conciergerie. In prison, she was respected by the guards, and was allowed the privilege of writing materials and occasional visits from devoted friends. There, she wrote her Appel à l'impartiale postérité, memoirs which display a strange alternation between self-praise and love of country, the trivial and the sublime.[11] She was tried on trumped-up charges of harbouring royalist sympathies, but it was plain that her death was part of the Mountain's purge of the Girondist opposition.Yet on 22 June 1793, in another letter to Buzot, she exclaimed with unyielding determination, "The tyrants may well oppress me, but demean me? Never, never![12]"

Imprisonment and death

In prison Roland struggled with her concept of a woman’s place in the nation of France after having been forced to lurk in the shadows to gain her own influence over the nation. Though she had earlier stated that she would "rather chew off (her own) fingers than become a writer", Madame Roland began writing her memoirs during her stay in prison, completing them in five months, with sections smuggled from the prison by her frequent guests. In her memoirs, she reflected upon her studies, passions, and political events. She had climbed the political scale by editing and modifying her husband’s platform but she established her historical significance through her recorded memoirs.

She proved women to be valuable active partners to political success. After Madame Roland helped her husband escape Paris, she accepted her fate of death on the guillotine as the only way to clear her name and reputation. Refusing to compromise her principles and remaining true to the ideals of Rousseau, Voltaire, and Plutarch, she died as a citizen of the Republic, not a subject of the monarchy. Her memoirs were published after her death, in 1795.

On 8 November 1793, she was conveyed to the guillotine. Before submitting to the executioner, she bowed before the clay statue of Liberty in the Place de la Révolution, uttering the famous remark for which she is remembered:[11]

'O Liberté, que de crimes on commet en ton nom! (Oh Liberty, what crimes are committed in thy name!)[13][lower-alpha 1]

Her body was buried in the Madeleine Cemetery. One week after her execution, her widower, Jean-Marie Roland, committed suicide on a country lane outside Rouen.

Her Mémoires de Madame Roland (1795) were written from prison where she was held as a Girondin sympathizer. It covers her work for the Girondins while her husband Jean-Marie Roland was Interior Minister. The book echoes such popular novels as Rousseau's Julie, or the New Heloise by linking her feminine virtue and motherhood to her sacrifice in a cycle of suffering and consolation. Roland says her mother's death was the impetus for her "odyssey from virtuous daughter to revolutionary heroine" as it introduced her to death and sacrifice - with the ultimate sacrifice of her own life for her political beliefs.[3]

Notes

- ↑ [alternately reported as] "O, Liberty! How they have duped you"(McShane 1992)

- ↑ Abbott 1904, p. 28.

- ↑ Abbott 1904, p. 27.

- 1 2 Walker 2001, pp. 403–419.

- ↑ Tarbell 1893, p. 556.

- 1 2 Szymanek 1996, pp. 99–122

- 1 2 3 "Jeanne-Marie Roland | French politician". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2017-12-26.

- ↑ Abbott 1904, p. 148.

- ↑ Abbott 1904, p. 111.

- ↑ Abbott 1904, p. 126.

- ↑ Lanson, Gustave, Choix de lettres du XVIIIe siècle, Librairie Hachette et Cie, 1908, p.674

- 1 2 3 Chisholm 1911, p. 463.

- ↑ Lanson, Gustave, Choix de lettres du XVIIIe siècle, Librairie Hachette et Cie, 1908, p.677

- ↑ McShane 1992.

References

- Abbott, John S. C. (1904). Madame Roland, Makers of History. Harper & Brother.

- McShane, Larry (24 April 1992). "Last Words of Those Executed Express Variety of Emotions". Daily News. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- Szymanek, Brigitte (Spring 1996). "French Women's Revolutionary Writings: Madame Roland or the Pleasure of the Mask". Tulsa Studies in Women's literature. 15 (1): 99–122. doi:10.2307/463976. JSTOR 463976.

- Tarbell, Ida M. (1893). "Madame Roland". Scribner's Magazine: 556.

- Walker, Lesley (Spring 2001). "Sweet and Consoling Virtue: The Memoirs of Madame Roland". Eighteenth-Century Studies. 34 (3): 403–419. doi:10.1353/ecs.2001.0034. JSTOR 30053986.

Attribution

- Madame Roland's Mémoires, first printed in 1820, subsequently edited by (amongst others) P. Faugere (Paris, 1864); C. A. Dauban (Paris, 1864); Jules Claretie (Paris, 1884); and C. Perroud (Paris, 1905).

- Madame Roland's Lettres inédites, some of which have been published by C. A. Dauban (Paris, 1867)

- Madame Roland's Lettres, C. Perroud, ed. (Paris, 1900–1902)

- Jean-Marie Roland de la Platière, De la Liberté du Travail (Paris, 1830)

- C. A. Dauban, Etude sur Madame Roland et son temps (Paris, 1864)

- V. Lamy, Deux femmes célèbres, Madame Roland et Charlotte Corday (Paris, 1884)

- C. Bader, Madame Roland, d'après des lettres et des manuscrits inédits (Paris, 1892)

- A. J. Lambert, Le menage de Madame Roland, trois années de correspondance amoureuse (Paris, 1896)

- Austin Dobson, Four Frenchwomen (London, 1890)

- Articles by C. Perroud in the review La Revolution française (1896–1899)

Further reading

- Abbott, John (2010). Madame Roland, Makers of History. FQ Books. ISBN 1-153-81253-3.

- Andress, David. The Terror: The Merciless War for Freedom in Revolutionary France

- Blashfield, Evangeline Wilbour. Manon Phlipon Roland: Early Years

- Blind, Mathilde. Madame Roland. Little, Brown & Company, 1898.

- Dalton, Susan. "Gender and the Shifting of Revolutionary Politics: The Case for Madame Roland Canadian Journal of History, (2001) 36#2

- Hanson, Paul R. Historical Dictionary of the French Revolution

- Kadane, Kathryn Ann. "The Real Difference between Manon Phlippon and Madame Roland", French Historical Studies, Vol. 3, No. 4, Autumn 1964.

- Linton, Marisa, Choosing Terror: Virtue, Friendship and Authenticity in the French Revolution, Oxford University Press, 2013.

- May, Gita. Madame Roland and the Age of Revolution, Columbia University Press, 1970.

- Pope-Hennessy, Dame Una Birch. Madame Roland: A Study in Revolution, Dodd, Mead & Co., 1918.

- Roland, Madame. The Private Memoirs of Madame Roland. Edited by Edward Gilpin Johnson, A. C. McClurg & Co., 1900.

- Schama, Simon. Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution. NY: Knopf, 1989.

- Scott, Samuel F. and Barry Rothaus. Historical Dictionary of the French Revolution 1789-1799 (1985) Vol. 2 pp 837–45 online

- Spalding, James Field. "Madame Roland", The American Catholic Quarterly Review, Vol. XXI, 1896.

- Syzmanek, Brigitte. “French Women’s Revolutionary Writings: Madame Roland or the Pleasure of the Mask”, Tulsa Studies in Women’s Literature, Vol. 15, No. 1, Spring 1996.

- Tarbell, Ida M. Madame Roland: A Biographical Study, Charles Scribner's Sons, 1896.

- Taylor, I. A. Life of Madame Roland, Hutchinson & Co., 1911.

- Walker, Lesley H. "Sweet and Consoling Virtue: The Memoirs of Madame Roland", Eighteenth-Century Studies 34(3), 2001.

- Winegarten, Renee. "Women and Politics: Madame Roland", New Criterion, Vol. 18, N°. 2, October 1999.

- Underwood, Sarah. Heroines of Free Thought, Somersby, 1876.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Madame Roland. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Madame Roland |

- Project Continua: Biography of Marie-Jeanne Phlippon Ronald Project Continua is a web-based multimedia resource dedicated to the creation and preservation of women’s intellectual history from the earliest surviving evidence into the 21st Century.