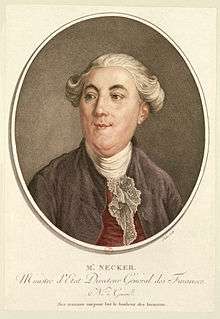

Jacques Necker

| Jacques Necker | |

|---|---|

| |

| Chief Minister of the French Monarch | |

|

In office 16 July 1789 – 3 September 1790 | |

| Monarch | Louis XVI |

| Preceded by | Baron of Breteuil |

| Succeeded by | Count of Montmorin |

|

In office 25 August 1788 – 11 July 1789 | |

| Monarch | Louis XVI |

| Preceded by | Archbishop de Brienne |

| Succeeded by | Baron of Breteuil |

| Controller-General of Finances | |

|

In office 25 August 1788 – 22 July 1789 | |

| Monarch | Louis XVI |

| Preceded by | Charles Alexandre de Calonne |

| Succeeded by | Charles Alexandre de Calonne |

|

In office 29 June 1777 – 19 May 1781 | |

| Monarch | Louis XVI |

| Preceded by | Louis Gabriel Taboureau |

| Succeeded by | Jean-François Joly |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

30 September 1732 Geneva, Republic of Geneva |

| Died |

9 April 1804 (aged 71) Coppet, Vaud, Switzerland |

| Political party | Non-partisan (Reformist) |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Children | Germaine |

| Profession | Banker, statesman |

Jacques Necker (IPA: [ʒak nɛkɛʁ]; 30 September 1732 – 9 April 1804) was a banker of Genevan origin who became a French statesman and finance minister for Louis XVI. He held the finance post during the period 1777-1781 and helped make decisions that were critical in creating political and social conditions that contributed to the outbreak of the French Revolution in 1789. "Necker is remembered today for taking the unprecedented step in 1781 of making public the country’s budget, a novelty in an absolute monarchy where the state of finances had always been kept a secret."[1] He was recalled to royal service just before the Revolution actually did start, but remained in office for only a brief period of time. His elder brother was the mathematician Louis Necker (1730–1804).

Early life

Necker was born in Geneva, at that time an independent republic. His father, Karl Friedrich Necker, was a native of Küstrin in Neumark, Prussia (now Kostrzyn nad Odrą, Poland). After the publication of some works on international law, he was elected a professor of public law at Geneva, of which he became a citizen. Jacques Necker was sent to Paris in 1747 to become a clerk in the bank of Isaac Vernet, a friend of his father. In 1762, he became a partner and by 1765, he had become very wealthy through successful financial speculations. Soon, he co-founded the bank of Thellusson, Necker et Compagnie with another Genevese, Peter Thellusson. Thellusson (also known as Pierre Thellusson) superintended the bank in London (his son was made a peer as Baron Rendlesham), while Necker was managing partner in Paris. Both partners became very rich by means of loans to the French treasury and speculations in grain.

In 1763, Necker fell in love with Madame de Verménou, the widow of a French officer. But while on a visit to Geneva, Madame de Verménou met Suzanne Curchod, who was the daughter of a pastor near Lausanne and had been engaged to Edward Gibbon. In 1764, Madame de Verménou brought Suzanne to Paris as her companion. There Necker, transferring his love from the wealthy widow to the poor Swiss girl, married Suzanne before the end of the year. On 22 April 1766, they had a daughter, Anne Louise Germaine Necker, who became a renowned author under the name of Madame de Staël.

Madame Necker encouraged her husband to try to find himself a public position. He accordingly became a syndic (or director) of the French East India Company, around which a fierce political debate revolved in the 1760s between the company's directors and shareholders and the royal ministry over its administration and the company's autonomy. "The ministry, concerned with the financial stability of the company, employed the Abbé Morellet to shift the debate from the rights of the shareholders to the advantages of commercial liberty over the company's privileged trading monopoly."[2] After showing his financial ability in its management, Necker defended the company's autonomy in an able memoir[3] against the attacks of Morellet in 1769.

Meanwhile, he made loans to the French government and was appointed resident at Paris by the republic of Geneva. Madame Necker entertained the leaders of the political, financial and literary worlds of Paris, and her Friday salon became as greatly frequented as the Mondays of Mme Geoffrin, or the Tuesdays of Mme Helvétius. In 1773, Necker won the prize of the Académie Française for a defense of state corporatism framed as a eulogy in honor of Louis XIV's minister Jean-Baptiste Colbert. In 1775, he published his Essai sur la législation et le commerce des grains, in which he attacked the free-trade policy of Turgot. His wife now believed he could get into office as a great financier and made him give up his share in the bank, which he transferred to his brother Louis.

Finance Minister of France

In June 1777,[4] Necker was made Director-General of Finance – he could not be named controller because of his Protestant faith.[5] He gained popularity in regulating the government's finances by attempting to divide the taille capitation tax more equally, abolishing a tax known as the vingtième d'industrie, and establishing monts de piété (establishments for loaning money on security). His greatest financial measures were his use of loans to help fund the French debt and his use of high interest rates rather than raising taxes.[6] He also advocated loans to finance French involvement in the American Revolution.[7]

In 1781, France was suffering financially, and because Necker was Director-General, he was blamed for the rather high debt accrued from the American Revolution.[8] While at court, Necker had made many enemies because of his reforming policies. Marie Antoinette was his most formidable enemy, so Louis – listening to Antoinette – would become a factor in Necker's resignation: Louis would not reform taxation to bring in more money to cover debts, nor would he listen to Necker and allow him to be a special adviser, because this was strongly opposed by the ministers. [9]

From 1777 to 1781, Necker was essentially in control of all of France's wealth. Near the end of this period, Necker published his most influential work: the Compte rendu au roi. In it, Necker summarized governmental income and expenditures to provide the first record of royal finances ever made public. It was meant to be an educational piece for the people, and in it he expressed his desire to create a well-informed, interested populace.[10] Before, the people had never considered governmental income and expenditure to be their concern, but the Compte rendu made them more proactive. This birth of public opinion and interest played an important role in the French Revolution. The statistics given in the Compte rendu were completely false and misleading. Necker wanted to show France in a strong financial position when the reality was much worse. He hid the crippling interest payments that France had to make on its massive 520 million livres in loans (largely used to finance the war in America) as normal expenditure. When he was criticized by his enemies for the Compte rendu, he made public his "Financial Summary for the King", which appeared to show that France had fought the war in America, paid no new taxes and still had a massive credit of 10 million livres of revenue.[11]

In retirement, Necker occupied himself with literature and produced his famous Traité de l'administration des finances de la France (1784). He also spent time with his beloved only child, who married the ambassador of Sweden in 1786 and became Madame de Staël. In 1787, Necker was banished to 40 leagues from Paris by a lettre de cachet for his very public exchange of pamphlets and memoirs attacking his successor as minister of finance, Charles Alexandre de Calonne. Yet in 1788, the country was struck by both economic and financial problems to the point of emergency, and Necker was called back to the office of Director-General of Finance to stop the deficit and save France from financial ruin.[12]

In the Revolution

Necker was viewed as the savior of France by many as the country stood on the brink of ruin, but his actions could not stop the French Revolution. Necker put a stop to the rebellion in the Dauphiné by legalizing the Assembly of Vizille, and then set to work to arrange for the summons of the Estates-General of 1789. He advocated doubling the representation of the Third Estate to satisfy the people. But he failed to address the matter of voting – rather than voting by head count, which is what the people wanted, voting remained as one vote for each estate.[13] Also, his address at the Estates-General was terribly miscalculated: it lasted for hours, and while those present expected a reforming policy to save the nation, he gave them financial data. This approach had serious repercussions on Necker's reputation; he appeared to consider the Estates-General to be a facility designed to help the administration rather than to reform government.[14]

Necker's dismissal on 11 July 1789, provoked by his decision not to attend Louis XVI's speech to the Estates-General, enraged the people of France and sparked rumors that the king meant to attack Paris or arrest the deputies. These fears and the foreign and French troops - called by the King - surrounding Paris and the National Assembly [15] provoked the storming of the Bastille on 14 July. The king recalled Necker on 19 July. He was received with joy in every city he traversed, but in Paris he again proved to be no statesman. Believing that he could save France alone, he refused to act with the Comte de Mirabeau or Marquis de Lafayette, the most prominent statesmen at the time. He caused the king's acceptance of the suspensive veto, by which he sacrificed his chief prerogative in September, and destroyed all chance of a strong executive by contriving the decree of 7 November, by which the ministry might not be chosen from the assembly. Financially, he proved equally incapable for a time of crisis and could not understand the need of such extreme measures as the establishment of assignats in order to keep the country quiet. Necker stayed in office until 1790, but his efforts to keep the financial situation afloat were ineffective. His popularity vanished and he resigned with a damaged reputation.[16] [17]

Retirement

Not without difficulty, he reached Coppet Castle, near Geneva, on an estate he had bought in 1784. Here he occupied himself with literature, but Madame Necker pined for her Paris salon and died soon after. He continued to live on at Coppet, under the care of his daughter Madame de Staël and his niece, Madame Necker de Saussure. But his time was past, and his books had no political influence. A momentary excitement was caused by the advance of the French armies in 1798, when he burnt most of his political papers. He died at Coppet on 9 April 1804.

Personal life

Family

His daughter Madame de Staël was to become a prominent figure in her own right and a leading opponent of Napoleon Bonaparte.

His nephew Jacques Necker married Albertine Necker de Saussure. Their son was the geologist and botanist Louis Albert Necker de Saussure.[18]

Religious beliefs

Places named after Jacques Necker

Notes

- ↑ Stael and the French Revolution Introduction by Aurelian Craiutu

- ↑ Kenneth Margerison, "The Shareholders' Revolt at the Compagnie des Indes: Commerce and Political Culture in Old Regime France" in French History 20. 1, pp. 25–51. Abstract.

- ↑ Réponse au Mémoire de M. l'Abbé Morellet, sur la Compagnie des Indes,

- ↑ M. Adcock, Analysing the French Revolution, Cambridge University Press, Australia 2007.

- ↑ Simon Schama, Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution (New York: Random House, 1989), 95.

- ↑ Donald F. Swanson and Andrew P. Trout, "Alexander Hamilton, 'the Celebrated Mr. Neckar,' and Public Credit," The William and Mary Quarterly 47, no. 3 (1990): 424.

- ↑ Nicola Barber, The French Revolution (London: Hodder Wayland, 2004), 11.

- ↑ George Taylor, review of Jacques Necker: Reform Statesman of the Ancien Regime, by Robert D. Harris, Journal of Economic History 40, no. 4 (1980): 878.

- ↑ Taylor, Jacques Necker: Reform, p. 877f.

- ↑ Schama, Citizens, 95.

- ↑ M. Adcock, Analysing the French Revolution, Cambridge University Press, Australia 2007.

- ↑ Jacques Necker

- ↑ Georges Lefebvre, The French Revolution: From its Origins to 1793, trans. Elizabeth Moss Evanson (London, Routledge Classics, 2001), 100.

- ↑ Schama, Citizens, 345–46.

- ↑ Godechot, Jacques. The Taking of the Bastille July 14, 1789.

- ↑ Furet and Ozuof, A Critical Dictionary,288.

- ↑ Doyle, William. The French Revolution. A Very Short Introduction.

- ↑ Biographical Index of Former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783–2002 (PDF). The Royal Society of Edinburgh. July 2006. ISBN 0 902 198 84 X.

Further reading

- Barber, Nicola. The French Revolution. London: Hodder Wayland, 2004.

- Furet, François, and Mona Ozuof. A Critical Dictionary of the French Revolution. (Belknap Press, 1989) pp 287–97

- Harris, R. D. Necker and the Revolution of 1789 (Lanham, MD, 1986)

- Lefebvre, Georges. The French Revolution: From its Origins to 1793. London: Routledge Classics, 2001.

- Schama, Simon. Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution. New York: Random House, 1989.

- Swanson, Donald F, and Andrew P. Trout. “Alexander Hamilton, the Celebrated Mr. Neckar,’ and Public Credit.” The William and Mary Quarterly (1990) 47#3 pp 422–430. in JSTOR

- Taylor, George. Review of Jacques Necker: Reform Statesman of the Ancien Regime, by Robert D. Harris. Journal of Economic History 40, no. 4 (1980): 877–879. doi:10.1017/s0022050700100518

- In French

- (in French) Bredin, Jean-Denis. Une singulière famille: Jacques Necker, Suzanne Necker et Germaine de Staël. Paris: Fayard, 1999 ( ISBN 2-213-60280-8).

See also

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jacques Necker. |

- Jacques Necker. Bibliography of Necker's publications.

- Jacques Necker. Chronology at University of Pennsylvania.

- Full text of Principes positifs de M. Neker … Positive principles of Mr. Neker, extracted from all his works

- Jacques Necker