Fatty liver

| Fatty liver | |

|---|---|

| Synonyms | Fatty liver disease (FLD), hepatic steatosis, simple steatosis |

| |

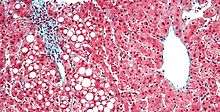

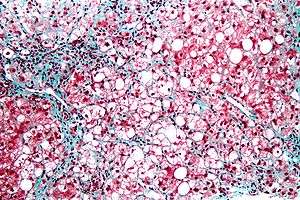

| Micrograph showing a fatty liver (macrovesicular steatosis), as seen in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Trichrome stain. | |

| Specialty | Gastroenterology |

Fatty liver, or hepatic steatosis or simple steatosis, is a reversible condition wherein large vacuoles of triglyceride fat accumulate in liver cells via the process of steatosis (i.e., abnormal retention of lipids within a cell). Despite having multiple causes, fatty liver can be considered a single disease that occurs worldwide in those with excessive alcohol intake and the obese (with or without effects of insulin resistance). The condition is also associated with other diseases that influence fat metabolism.[1] When this process of fat metabolism is disrupted, the fat can accumulate in the liver in excessive amounts, thus resulting in a fatty liver.[2] It is difficult to distinguish alcoholic FLD, which is part of alcoholic liver disease, from nonalcoholic FLD (NAFLD), and both show microvesicular and macrovesicular fatty changes at different stages.

The accumulation of fat in alcoholic or non-alcoholic steatosis may also be accompanied by a progressive inflammation of the liver (hepatitis), called steatohepatitis. This more severe condition may be termed either alcoholic steatohepatitis or non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH).

Signs and symptoms

Complications

Fatty liver can develop into a fibrosis or a liver cancer.[3] For people affected by NAFLD, the 10-year survival rate was about 80%. The rate of progression of fibrosis in NASH is estimated to one per 7 years and 14 years for NAFLD, with an increasing speed.[4][5] There is a strong relationship between these pathologies and metabolic illnesses (diabetes type II, metabolic syndrome). These pathologies can also affect non-obese people, who are then at a higher risk.[3]

Less than 10% of people with cirrhotic alcoholic FLD will develop hepatocellular carcinoma,[6] the liver cancer, but up to 45% people with NASH without cirrhosis can develop hepatocellular carcinoma.[7]

Causes

Fatty liver (FL) is commonly associated with metabolic syndrome (diabetes, hypertension, obesity, and dyslipidemia), but can also be due to any one of many causes:[8][9]

- Metabolic

- abetalipoproteinemia, glycogen storage diseases, Weber–Christian disease, acute fatty liver of pregnancy, lipodystrophy

- Nutritional

- obesity, malnutrition, total parenteral nutrition, severe weight loss, refeeding syndrome, jejunoileal bypass, gastric bypass, jejunal diverticulosis with bacterial overgrowth

- Drugs and toxins

- amiodarone, methotrexate, diltiazem, expired tetracycline, highly active antiretroviral therapy, glucocorticoids, tamoxifen,[10] environmental hepatotoxins (e.g., phosphorus, mushroom poisoning)

- Alcohol

- Alcoholism is one of the causes of fatty liver due to production of toxic metabolites like aldehydes during metabolism of alcohol in the liver. This phenomenon most commonly occurs with chronic alcoholism.

- Other

- celiac disease,[11] inflammatory bowel disease, HIV, hepatitis C (especially genotype 3), and alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency[12]

Pathology

Fatty change represents the intracytoplasmatic accumulation of triglycerides (neutral fats). At the beginning, the hepatocytes present small fat vacuoles (liposomes) around the nucleus (microvesicular fatty change). In this stage, liver cells are filled with multiple fat droplets that do not displace the centrally located nucleus. In the late stages, the size of the vacuoles increases, pushing the nucleus to the periphery of the cell, giving characteristic signet ring appearance (macrovesicular fatty change). These vesicles are well-delineated and optically "empty" because fats dissolve during tissue processing. Large vacuoles may coalesce and produce fatty cysts, which are irreversible lesions. Macrovesicular steatosis is the most common form and is typically associated with alcohol, diabetes, obesity, and corticosteroids. Acute fatty liver of pregnancy and Reye's syndrome are examples of severe liver disease caused by microvesicular fatty change.[13] The diagnosis of steatosis is made when fat in the liver exceeds 5–10% by weight.[1][14][15]

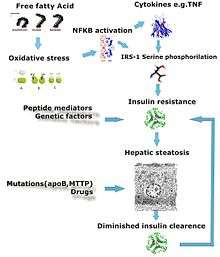

Defects in fatty acid metabolism are responsible for pathogenesis of FLD, which may be due to imbalance in energy consumption and its combustion, resulting in lipid storage, or can be a consequence of peripheral resistance to insulin, whereby the transport of fatty acids from adipose tissue to the liver is increased.[1][16] Impairment or inhibition of receptor molecules (PPAR-α, PPAR-γ and SREBP1) that control the enzymes responsible for the oxidation and synthesis of fatty acids appears to contribute to fat accumulation. In addition, alcoholism is known to damage mitochondria and other cellular structures, further impairing cellular energy mechanism. On the other hand, non-alcoholic FLD may begin as excess of unmetabolised energy in liver cells. Hepatic steatosis is considered reversible and to some extent nonprogressive if the underlying cause is reduced or removed.

Severe fatty liver is sometimes accompanied by inflammation, a situation referred to as steatohepatitis. Progression to alcoholic steatohepatitis (ASH) or non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) depends on the persistence or severity of the inciting cause. Pathological lesions in both conditions are similar. However, the extent of inflammatory response varies widely and does not always correlate with degree of fat accumulation. Steatosis (retention of lipid) and onset of steatohepatitis may represent successive stages in FLD progression.[17]

Liver disease with extensive inflammation and a high degree of steatosis often progresses to more severe forms of the disease.[18] Hepatocyte ballooning and necrosis of varying degrees are often present at this stage. Liver cell death and inflammatory responses lead to the activation of hepatic stellate cells, which play a pivotal role in hepatic fibrosis. The extent of fibrosis varies widely. Perisinusoidal fibrosis is most common, especially in adults, and predominates in zone 3 around the terminal hepatic veins.[19]

The progression to cirrhosis may be influenced by the amount of fat and degree of steatohepatitis and by a variety of other sensitizing factors. In alcoholic FLD, the transition to cirrhosis related to continued alcohol consumption is well-documented, but the process involved in non-alcoholic FLD is less clear.

Diagnosis

| Flow chart for diagnosis, modified from[9] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ‡ Criteria for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: consumption of ethanol less than 20 g/day for women and 30 g/day for men[20] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Most individuals are asymptomatic and are usually discovered incidentally because of abnormal liver function tests or hepatomegaly noted in unrelated medical conditions. Elevated liver biochemistry is found in 50% of patients with simple steatosis.[21] The serum alanine transaminase level usually is greater than the aspartate transaminase level in the nonalcoholic variant and the opposite in alcoholic FLD (AST:ALT more than 2:1).

Imaging studies are often obtained during the evaluation process. Ultrasonography reveals a "bright" liver with increased echogenicity. Medical imaging can aid in diagnosis of fatty liver; fatty livers have lower density than spleens on computed tomography (CT), and fat appears bright in T1-weighted magnetic resonance images (MRIs). Magnetic resonance elastography, a variant of magnetic resonance imaging, is investigated as a non-invasive method to diagnose fibrosis progression.[22] Histological diagnosis by liver biopsy is the most accurate measure of fibrosis and liver fat progression as of 2018.[3]

Treatment

The treatment of fatty liver depends on its cause, and, in general, treating the underlying cause will reverse the process of steatosis if implemented at an early stage. Fatty liver can be caused by different factors that are not all identified. However, two known causes of fatty liver disease are an excess consumption of alcohol and a prolonged diet with a high proportion of calories coming from carbohydrates. For people with NAFLD or NASH, weight loss via a combination of diet and exercise was shown to improve or resolve the disease.[3] In more serious cases, medications that decrease insulin resistance, hyperlipidemia, and those that induce weight loss such as bariatric surgery as well as Vitamin E have been shown to improve or resolve liver function.[3][9]

Bariatric surgery, while not recommended in 2017 as a treatment for fatty liver disease (FLD) alone, has been shown to revert FLD, NAFLD, NASH and advanced steatohepatitis in over 90% of people who have undergone this surgery for the treatment of obesity.[3][23]

In the case of long-term total parenteral nutrition induced fatty liver disease, choline has been shown to alleviate symptoms.[24][25][26] This may be due to a deficiency in the methionine cycle.[27]

Epidemiology

The prevalence of FLD in the general population ranges from 10% to 24% in various countries.[8] However, the NAFLD condition is observed in up to 80% of obese people, 35% of whom progress to NASH,[28] and in up to 20% of normal weight people,[5] despite no evidence of excessive alcohol consumption. FLD is the most common cause of abnormal liver function tests in the United States.[8] Fatty liver is more prevalent in hispanic people than white, with black people having the lowest susceptibility.[5]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Reddy JK, Rao MS (May 2006). "Lipid metabolism and liver inflammation. II. Fatty liver disease and fatty acid oxidation". American Journal of Physiology. Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology. 290 (5): G852–8. doi:10.1152/ajpgi.00521.2005. PMID 16603729.

- ↑ Cutler N. "Symptoms of Fatty Liver". Retrieved 18 November 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Chalasani, Naga; Younossi, Zobair; Lavine, Joel E.; Charlton, Michael; Cusi, Kenneth; Rinella, Mary; Harrison, Stephen A.; Brunt, Elizabeth M.; Sanyal, Arun J. (January 2018). "The diagnosis and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Practice guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases". Hepatology. 67 (1): 328–357. doi:10.1002/hep.29367.

- ↑ Singh, Siddharth; Allen, Alina M.; Wang, Zhen; Prokop, Larry J.; Murad, Mohammad H.; Loomba, Rohit (April 2015). "Fibrosis Progression in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver vs Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Paired-Biopsy Studies". Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 13 (4): 643–654.e9. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2014.04.014. PMC 4208976.

- 1 2 3 Younossi, Zobair; Anstee, Quentin M.; Marietti, Milena; Hardy, Timothy; Henry, Linda; Eslam, Mohammed; George, Jacob; Bugianesi, Elisabetta (20 September 2017). "Global burden of NAFLD and NASH: trends, predictions, risk factors and prevention". Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 15 (1): 11–20. doi:10.1038/nrgastro.2017.109.

- ↑ Qian Y, Fan JG (May 2005). "Obesity, fatty liver and liver cancer". Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International. 4 (2): 173–7. PMID 15908310.

- ↑ Bellentani, Stefano (January 2017). "The epidemiology of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease". Liver International. 37: 81–84. doi:10.1111/liv.13299.

- 1 2 3 Angulo P (April 2002). "Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease". The New England Journal of Medicine. 346 (16): 1221–31. doi:10.1056/NEJMra011775. PMID 11961152.

- 1 2 3 Bayard M, Holt J, Boroughs E (June 2006). "Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease". American Family Physician. 73 (11): 1961–8. PMID 16770927.

- ↑ Osman KA, Osman MM, Ahmed MH (January 2007). "Tamoxifen-induced non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: where are we now and where are we going?". Expert Opinion on Drug Safety. 6 (1): 1–4. doi:10.1517/14740338.6.1.1. PMID 17181445.

- ↑ Marciano F, Savoia M, Vajro P (February 2016). "Celiac disease-related hepatic injury: Insights into associated conditions and underlying pathomechanisms". Digestive and Liver Disease. 48 (2): 112–9. doi:10.1016/j.dld.2015.11.013. PMID 26711682.

- ↑ Valenti L, Dongiovanni P, Piperno A, Fracanzani AL, Maggioni M, Rametta R, Loria P, Casiraghi MA, Suigo E, Ceriani R, Remondini E, Trombini P, Fargion S (October 2006). "Alpha 1-antitrypsin mutations in NAFLD: high prevalence and association with altered iron metabolism but not with liver damage". Hepatology. 44 (4): 857–64. doi:10.1002/hep.21329. PMID 17006922.

- ↑ Goldman L (2003). Cecil Textbook of Medicine – 2-Volume Set, Text with Continually Updated Online Reference. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Company. ISBN 978-0-7216-4563-6.

- ↑ Adams LA, Lymp JF, St Sauver J, Sanderson SO, Lindor KD, Feldstein A, Angulo P (July 2005). "The natural history of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a population-based cohort study". Gastroenterology. 129 (1): 113–21. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2005.04.014. PMID 16012941.

- ↑ Crabb DW, Galli A, Fischer M, You M (August 2004). "Molecular mechanisms of alcoholic fatty liver: role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha". Alcohol. 34 (1): 35–8. doi:10.1016/j.alcohol.2004.07.005. PMID 15670663.

- ↑ Medina J, Fernández-Salazar LI, García-Buey L, Moreno-Otero R (August 2004). "Approach to the pathogenesis and treatment of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis". Diabetes Care. 27 (8): 2057–66. doi:10.2337/diacare.27.8.2057. PMID 15277442.

- ↑ Day CP, James OF (April 1998). "Steatohepatitis: a tale of two "hits"?". Gastroenterology. 114 (4): 842–5. doi:10.1016/S0016-5085(98)70599-2. PMID 9547102.

- ↑ Gramlich T, Kleiner DE, McCullough AJ, Matteoni CA, Boparai N, Younossi ZM (February 2004). "Pathologic features associated with fibrosis in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease". Human Pathology. 35 (2): 196–9. doi:10.1016/j.humpath.2003.09.018. PMID 14991537.

- ↑ Zafrani ES (January 2004). "Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: an emerging pathological spectrum". Virchows Archiv. 444 (1): 3–12. doi:10.1007/s00428-003-0943-7. PMID 14685853.

- ↑ Adams LA, Angulo P, Lindor KD (March 2005). "Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease". CMAJ. 172 (7): 899–905. doi:10.1503/cmaj.045232. PMC 554876. PMID 15795412.

- ↑ Sleisenger M (2006). Sleisenger and Fordtran's Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Company. ISBN 978-1-4160-0245-1.

- ↑ Singh, Siddharth; Venkatesh, Sudhakar K.; Loomba, Rohit; Wang, Zhen; Sirlin, Claude; Chen, Jun; Yin, Meng; Miller, Frank H.; Low, Russell N.; Hassanein, Tarek; Godfrey, Edmund M.; Asbach, Patrick; Murad, Mohammad Hassan; Lomas, David J.; Talwalkar, Jayant A.; Ehman, Richard L. (28 August 2015). "Magnetic resonance elastography for staging liver fibrosis in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a diagnostic accuracy systematic review and individual participant data pooled analysis". European Radiology. 26 (5): 1431–1440. doi:10.1007/s00330-015-3949-z.

- ↑ "Fatty Liver: Overview, Pathophysiology, Etiology". 2017-01-25.

- ↑ Buchman AL, Dubin MD, Moukarzel AA, Jenden DJ, Roch M, Rice KM, Gornbein J, Ament ME (November 1995). "Choline deficiency: a cause of hepatic steatosis during parenteral nutrition that can be reversed with intravenous choline supplementation". Hepatology. 22 (5): 1399–403. doi:10.1002/hep.1840220510. PMID 7590654.

- ↑ Buchman AL, Dubin M, Jenden D, Moukarzel A, Roch MH, Rice K, Gornbein J, Ament ME, Eckhert CD (April 1992). "Lecithin increases plasma free choline and decreases hepatic steatosis in long-term total parenteral nutrition patients". Gastroenterology. 102 (4 Pt 1): 1363–70. doi:10.1016/0016-5085(92)70034-9. PMID 1551541.

- ↑ Buchman AL, Ament ME, Sohel M, Dubin M, Jenden DJ, Roch M, Pownall H, Farley W, Awal M, Ahn C (2016). "Choline deficiency causes reversible hepatic abnormalities in patients receiving parenteral nutrition: proof of a human choline requirement: a placebo-controlled trial". JPEN. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. 25 (5): 260–8. doi:10.1177/0148607101025005260. PMID 11531217.

- ↑ Hollenbeck CB (August 2010). "The importance of being choline". Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 110 (8): 1162–5. doi:10.1016/j.jada.2010.05.012. PMID 20656090.

- ↑ Hamaguchi M, Kojima T, Takeda N, Nakagawa T, Taniguchi H, Fujii K, Omatsu T, Nakajima T, Sarui H, Shimazaki M, Kato T, Okuda J, Ida K (November 2005). "The metabolic syndrome as a predictor of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease". Annals of Internal Medicine. 143 (10): 722–8. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-143-10-200511150-00009. PMID 16287793.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

- American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases

- American Liver Foundation

- Fatty Liver Disease, Canadian Liver Foundation

- 00474 at CHORUS

- Photo at Atlas of Pathology

- Healthdirect