Foehn wind

A föhn or foehn (UK: /fɜːrn/,[2][3] US: /feɪn/) is a type of dry, warm, down-slope wind that occurs in the lee (downwind side) of a mountain range.

It is a rain shadow wind that results from the subsequent adiabatic warming of air that has dropped most of its moisture on windward slopes (see orographic lift). As a consequence of the different adiabatic lapse rates of moist and dry air, the air on the leeward slopes becomes warmer than equivalent elevations on the windward slopes. Föhn winds can raise temperatures by as much as 14 °C (25 °F)[4] in just a matter of minutes. Central Europe enjoys a warmer climate due to the Föhn, as moist winds off the Mediterranean Sea blow over the Alps.

In some regions, föhn winds are associated with causing "circulatory problems", headaches, or similar ailments.[5] Researchers have found, however, the foehn wind's warm temperature to be beneficial to humans in most situations, and have theorised that the reported negative effects may be a result of secondary factors, such as changes in the electrical field or in the ion state of the atmosphere, the wind's relatively low humidity, or the generally unpleasant sensation of being in an environment with strong and gusty winds.[5]

Causes

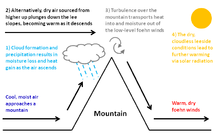

Explanations of the foehn warming and drying effect in popular literature or on the web often single out just one causal mechanism (#1 - Condensation and Precipitation - in the below), but there are in fact four known causes[6] (illustrated in the schematic at top right of this page). These mechanisms often act together, with their contributions varying depending on the size and shape of the mountain barrier and on the meteorological conditions, for example the upstream wind speed, temperature and humidity.

1) Condensation and precipitation: When air is forced upwards over elevated terrain, it expands and cools due to the decrease in pressure with height. Since colder air can hold less water vapour, moisture condenses to form clouds and precipitates as rain or snow above the mountain's upwind slopes. The change of state from vapour to liquid water is accompanied by heating, and the subsequent removal of moisture as precipitation renders this heat gain irreversible, leading to the warm, dry foehn conditions in the mountain's lee. This mechanism has become a popular textbook example of atmospheric thermodynamics and it lends itself to attractive diagrams. However the common occurrence of 'dry' foehn events, where there is no precipitation, implies there must be other mechanisms.

2) Isentropic draw-down (the draw-down of warmer, drier air from aloft): When the approaching winds are insufficiently strong to propel the low-level air up and over the mountain barrier, the airflow is said to be 'blocked' by the mountain and only air higher up near mountain-top level is able to pass over and down the lee slopes as foehn winds. These higher source regions provide foehn air that becomes warmer and drier on the leeside after it is compressed with descent due to the increase in pressure towards the surface.

3) Mechanical mixing: When river water passes over rocks, turbulence is generated in the form of rapids, and white water reveals the turbulent mixing of the water with the air above. Similarly, as air passes over mountains, turbulence occurs and the atmosphere is mixed in the vertical. This mixing generally leads to a downward warming and upward moistening of the cross-mountain airflow, and consequently to warmer, drier foehn winds in the valleys downwind.

4) Radiative warming: Dry foehn conditions are responsible for the occurrence of rain shadows in the lee of mountains, where clear, sunny conditions prevail. This often leads to greater daytime radiative (solar) warming under foehn conditions. This type of warming is particularly important in cold regions where snow or ice melt is a concern and/or avalanches are a risk.

Effects

Winds of this type are also called "snow-eaters" for their ability to make snow and ice melt or sublimate rapidly. This is a result not only of the warmth of foehn air, but also its low relative humidity. Accordingly, foehn winds are known to contribute to the disintegration of ice shelves in the polar regions.[7]

Foehn winds are notorious among mountaineers in the Alps, especially those climbing the Eiger, for whom the winds add further difficulty in ascending an already difficult peak.

They are also associated with the rapid spread of wildfires, making some regions which experience these winds particularly fire-prone.

Anecdotally, residents in areas of frequent foehn winds report a variety of illnesses ranging from migraines to psychosis. The first clinical review of these effects was published by the Austrian physician Anton Czermak in the 19th century.[8] A study by the Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München found that suicide and accidents increased by 10 percent during foehn winds in Central Europe. The causation of Föhnkrankheit (English: Foehn-sickness) is yet unproven. Labeling for preparations of aspirin combined with caffeine, codeine and the like will sometimes include Föhnkrankheit amongst the indications.[9] Evidence for effects from Chinook winds remain anecdotal.

Etymology

The name Foehn (German: Föhn, pronounced [ˈføːn]) arose in the Alpine region. Originating from Latin (ventus) favonius, a mild west wind of which Favonius was the Roman personification[10] and probably transmitted by Romansh: favuogn or just fuogn, the term was adopted as Old High German: phōnno. In the Southern Alps, the phenomenon is known as föhn but also Italian: favonio and fen in Croatian and Slovene. The German word "Fön" (without the "H", but pronounced the same way), a genericized trademark, also means "hairdryer," and the form "phon" is used in French-speaking parts of Switzerland as well as in Italy. The form "fen" is used in Croatia and Slovenia.

Local examples

Regionally, these winds are known by many different names. These include:

- in Africa

- Bergwind in South Africa

- in the Americas

- The Brookings Effect on the southwestern coast of Oregon, also known as the Chetco Effect.

- Chinook winds east of the Rocky Mountains and the Cascade Range in the United States and Canada, and north, east and west of the Chugach Mountains of Alaska, United States

- Foehn winds in the foothills of the southern Appalachian mountains[11], which can be unusual compared to other foehn winds in that the relative humidity typically changes little due to the increased moisture in the source air mass[12]

- The Santa Ana winds of southern California, including the Sundowner winds of Santa Barbara, are in some ways similar to the Föhn, but originate in dry deserts as a katabatic wind.

- Puelche wind in Chile

- Suêtes on the west coast of Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia, Canada

- Zonda winds in Argentina

- in Antarctica

- Föhn wall on Signy Island, South Orkneys

- in Asia

- Garmesh, Garmij, Garmbaad (Warm Wind): (Persian: گرمباد, Gilaki: گرمش) in Gilan region, in the south west of Caspian Sea in Iran

- Kumagaya, Saitama, Japan. The city recorded air temperature of 40.9 °C (105.6 °F), breaking the 74-year record for the highest temperature recorded in Japan. "Very Hot! Kumagaya" (あついぞ!熊谷) is the catch phrase of the city.

- Loo in Indo-Gangetic Plain

- 燒風(sio-hong) in Taiwan

- Warm Braw in the Schouten Islands north of West Papua, Indonesia.[13]

- Wuhan in China is famously known as one of the Three Furnaces on account of its extremely hot weather in summer resulting from the adiabatic warming effect created by mountains further south.

- in Oceania

- Föhn in Penrith and Richmond, New South Wales, Australia. Often associated with heavy orographic lifting on the windward side of the Blue Mountains[14]

- The Nor'wester in Hawkes Bay, Canterbury, and Otago, New Zealand[15]

- in Europe

- Favonio in Ticino and Italy

- Fen in northwest Slovenia

- Fogony in the Catalan Pyrenees

- Föhn or Foehn in Austria, southern Germany, Switzerland, France and Liechtenstein

- Föhn in Ostrobothnia and Western Lapland in Finland as moist air crosses Scandinavian Mountains and dries up.

- Halny in the Carpathian Mountains, Poland (Central Europe)

- The Helm Wind, on the Pennines in the Eden Valley, Cumbria, England

- Hnjúkaþeyr in Icelandic

- Lyvas wind in Thessalian plain, Voiotia plain, Plain of Thessaloniki, Elefsina and Athens in Greece

- Košava (Koshava) wind in Serbia that blows along the Danube River[16][17]

- Nortada in Cascais, and most notoriously in Guincho Beach, making it one of the best windsurfing spots in Europe

- Ponentà in Valencia (eastern Spain)

- Terral in Málaga (southern Spain)

- Vântul Mare in the Carpathian Mountains, Romania

- Viento del Sur (Southern Wind) or Hego haizea in Basque in the Cantabrian region (northern Spain)

- North-East Scotland, south-westerly winds create a föhn effect bringing relatively warm temperatures on the lee side of the Grampians and Cairngorm mountain ranges. The reverse occurs when south-easterly winds create a föhn effect to the North-West of Scotland, with the air drying out and warming up as it crosses the Grampians and Cairngorms from east to west. With the prevailing wind direction in the UK being from the west or south west, the föhn effect in Scotland is more common in the North-East of the country, with the west of Scotland being much wetter.

In popular culture

- Peter Camenzind, a novel by Hermann Hesse, refers, at length, to the Alpine föhn.

- The Föhn was mentioned by Queen's lead guitarist Brian May while talking about the band's grim Munich recording studio experience in 1982.[18]

- The Föhn is attributed by the narrator of Jens Bjørneboe' 1969 novel Kruttårnet (Powderhouse) as the traditional cause of occasional unprovoked murders in a small Alpine town.

- The Föhn is used for the letter F in "Crazy ABC's" from the album Snacktime! by the Barenaked Ladies.

- The threat of the Föhn drives the protagonists Ayla and Jondalar in Jean M. Auel's The Plains of Passage over a glacier before the spring melt. The pair make references to the mood altering phenomena of the wind, similar to those of the Santa Ana wind.

- In Southern Germany, this wind is supposed to cause disturbed mood. Heinrich Hoffmann notes in his book Hitler Was My Friend that on the evening of September 18, 1931, when Adolf Hitler and Hoffmann left their Munich apartment on an election campaign tour, Hitler had complained about a bad mood and feeling. Hoffmann tried to pacify Hitler about the Austrian föhn wind as the possible reason. Hours later, Hitler's niece, Geli Raubal, was found dead in his Munich apartment. It was declared that she had committed suicide though it had conflicting testimonies from the witnesses present.

- A foehn wind is responsible for the grounding of a US Navy destroyer off Greenland's west coast in the Second World War novel The Ice Brothers by Sloan Wilson.

- It's mentioned as a surprise change in weather during the ascent of Switzerland's Eiger in the book The Eiger Sanction by Trevanian.

- The föhn blowing through Zurich torments the characters in Robert Anton Wilson's Masks of the Illuminati.

- Joan Didion explores the nature of various Foehn winds in her essay "The Santa Ana".

- "Foehn" is a magic spell that deals wind/heat damage in Star Ocean: The Second Story.

- "Foehn" is the last word in A Nest of Ninnies, a 1969 novel by John Ashbery and James Schuyler. Ashbery claimed that he and Schuyler chose this particular word because "people, if they bothered to, would have to open the dictionary to find out what the last word in the novel meant."[19]

- In the 1985 Italian horror film "Phenomena" Donald Pleasence's character offers the Foehn winds as a possible cause of Jennifer Connelly's characters sleepwalking.

- "The Foehn Revolt" is the name of a faction in Mental Omega, a popular modification for Command & Conquer: Yuri's Revenge. The name symbolises that warfare changes like the wind, as the in-game faction uses the most modern weaponry to defeat its arch enemy "The Epsilon Army" .

See also

References

- McKnight, TL & Hess, Darrel (2000). Foehn/Chinook Winds. In Physical Geography: A Landscape Appreciation, p. 132. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-020263-0.

Footnotes

- ↑ Elvidge, Andrew D.; Renfrew, Ian A. (14 May 2015). "The Causes of Foehn Warming in the Lee of Mountains". Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. 97 (3): 455–466. Bibcode:2016BAMS...97..455E. doi:10.1175/bams-d-14-00194.1. Retrieved 23 April 2017.

- ↑ "föhn". Oxford Dictionaries.

- ↑ "föhn". Collins Dictionary.

- ↑ "South Dakota Weather History and Trivia for January". National Weather Service Weather Forecast Office. February 8, 2006. See January 22 entry.

- 1 2 TULLER, STANTON E. (April 1980). "The Effects of a Foehn Wind on Human Thermal Exchange: The Canterbury Nor'wester". New Zealand Geographer. 36 (1): 11–19. doi:10.1111/j.1745-7939.1980.tb01919.x. Retrieved 21 May 2017.

- ↑ Elvidge, Andrew D.; Renfrew, Ian A. (14 May 2015). "The Causes of Foehn Warming in the Lee of Mountains". Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. 97 (3): 455–466. Bibcode:2016BAMS...97..455E. doi:10.1175/bams-d-14-00194.1. Retrieved 23 April 2017.

- ↑ Elvidge, Andrew D.; Renfrew, Ian A.; King, John C.; Orr, Andrew; Lachlan-Cope, Tom A. (January 2016). "Foehn warming distributions in nonlinear and linear flow regimes: a focus on the Antarctic Peninsula". Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society. 142 (695): 618–631. Bibcode:2016QJRMS.142..618E. doi:10.1002/qj.2489.

- ↑ Giannini, AJ; Malone, DA; Piotrowski, TA (1986). "The serotonin irritation syndrome--a new clinical entity?". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 47 (1): 22–5. PMID 2416736.

- ↑ See the documentary: Snow Eater (the English translation of Canadian First Nations word phonetically pronounced chinook). telefilm.ca Archived 2013-10-17 at the Wayback Machine..

- ↑ Concise Oxford Dictionary, 10th edition, Oxford University Press, entry föhn.

- ↑ Gaffin, David M. (2007). "Foehn Winds That Produced Large Temperature Differences near the Southern Appalachian Mountains". Weather and Forecasting. 22 (1): 145–159. Bibcode:2007WtFor..22..145G. doi:10.1175/WAF970.1.

- ↑ Gaffin, David M. (2002). "Unexpected Warming Induced by Foehn Winds in the Lee of the Smoky Mountains". Weather and Forecasting. 17 (4): 907–915. Bibcode:2002WtFor..17..907G. doi:10.1175/1520-0434(2002)017<0907:UWIBFW>2.0.CO;2.

- ↑ "Wind Names". ggweather.com.

- ↑ Sharples, J.J. Mills, G.A., McRae, R.H.D., Weber, R.O. (2010) Elevated fire danger conditions associated with foehn-like winds in southeastern Australia. Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology.

- ↑ Relph, D. "The Canterbury nor'wester," New Zealand Geographic. Retrieved 17 February 2018.

- ↑ Romanić; et al. (2015). "Contributing factors to Koshava wind characteristics". International Journal of Climatology. Bibcode:2016IJCli..36..956R. doi:10.1002/joc.4397. Retrieved 20 August 2015.

- ↑ Romanić; et al. (2015). "Long-term trends of the 'Koshava' wind during the period 1949–2010". International Journal of Climatology. 35 (3): 288–302. Bibcode:2015IJCli..35..288R. doi:10.1002/joc.3981. Retrieved 20 August 2015.

- ↑ "Brian News - September 2012". brianmay.com.

- ↑ "Paris Review - The Art of Poetry No. 33, John Ashbery". theparisreview.org.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Foehn wind. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Föhn. |

- Photo of Föhnmauer The strong clouds at the mountain ridges where the föhn winds form are called Föhnmauer (Föhn wall).

- Illustration

- Movie of a Föhn situation in the Swiss Alps

- East Scotland warmth due to Foehn Effect

- Foehn chart provided by meteomedia/meteocentrale.ch