Eutaw, Alabama

| Eutaw, Alabama | |

|---|---|

| City | |

Downtown Eutaw, Alabama | |

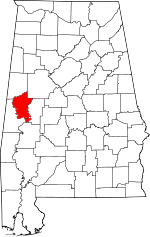

Location of Eutaw in Greene County, Alabama. | |

| Coordinates: 32°50′26″N 87°53′20″W / 32.84056°N 87.88889°WCoordinates: 32°50′26″N 87°53′20″W / 32.84056°N 87.88889°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Alabama |

| County | Greene |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Raymond Steele |

| • City Council |

Members

|

| Area[1] | |

| • Total | 12.01 sq mi (31.10 km2) |

| • Land | 11.93 sq mi (30.91 km2) |

| • Water | 0.08 sq mi (0.20 km2) |

| Elevation | 217 ft (66 m) |

| Population (2010)[2] | |

| • Total | 2,934 |

| • Estimate (2017)[3] | 2,687 |

| • Density | 225.17/sq mi (86.94/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (Central (CST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

| ZIP code | 35462 |

| Area code(s) | 205 |

| FIPS code | 01-24664 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0118059 |

Eutaw (/ˈjuːtɔː/ YEW-taw) is a city in and the county seat of Greene County, Alabama, United States. At the 2010 census the population was 2,934.[2] The city was named in honor of the Battle of Eutaw Springs, the last engagement of the American Revolutionary War in the Carolinas.

Schools in Eutaw include Robert Brown Middle School, Eutaw Primary School, and Greene County High School.

History

Eutaw was laid out in December 1838 at the time that Greene County voters chose to relocate the county seat from Erie, which was located on the Black Warrior River. It was incorporated by an act of the state legislature on January 2, 1841.[4]

As the county seat, it also developed as the trading center for the county, which developed an economy based on cultivation and processing of cotton, the chief commodity crop in the antebellum years. The crop was lucrative for major planters, who depended on the labor of enslaved African Americans, and they built a number of fine homes in the city.

Many have been preserved into the late 20th and early 21st centuries. Eutaw has twenty-seven antebellum structures on the National Register of Historic Places. Twenty-three of these are included in the Antebellum Homes in Eutaw multiple property submission. The Coleman-Banks House, Old Greene County Courthouse, First Presbyterian Church, and Kirkwood are listed individually. Additionally, the Greene County Courthouse Square District is a listed historic district in the heart of downtown. A nearby property, Everhope Plantation, is also listed in the register.[5]

During the Reconstruction Era, Eutaw was the site of a number of Klan murders and acts by insurgents who were not finished with the war. The county courthouse was burned in 1868; the prevailing theory for the burning of the courthouse is that it was intended to destroy the records of some 1,800 suits by freedmen against planters, which were about to be prosecuted.[6] On March 31, 1870, the Republican county solicitor, Alexander Boyd, was shot and killed at his hotel when resisting being taken by a masked group of armed Klan members.[6] (An early-20th century historian of the Klan claimed the group was from Mississippi.[7]) That same night, James Martin, a black Republican leader, was killed near his home in Union, Alabama, also in Greene County.[8]

In the fall of 1870, in the run-up to the gubernatorial election, two more black Republican politicians were killed in Greene County. On October 25, 1870, white members attacked a Republican rally in the courthouse square that had attracted 2,000 blacks, who mostly voted Republican. The Eutaw riot resulted in four black deaths and some 54 wounded outside the county courthouse. Most blacks did not vote in the fall's election, which showed a majority in Greene County for the Democratic candidate for governor.[9][10]

Whites continued to use violence and intimidation of blacks across the state to suppress their voting and to regain power in the state legislature. In many places in Alabama, lynchings increased in the late 19th century into the early 20th century. None was documented in Greene County during this period, according to a 2015 report by the Equal Justice Initiative.[11] On May 16, 1892, Sheriff Cullen and Deputy Sheriff E. C. Meredith of Greene County, with aid of a posse, distinguished themselves by going into Pickens County after a lynch mob of about 50 men. The mob had taken African-American suspect Jim Jones from the Greene County jail, saying they were going to hang him in Carrollton for an alleged crime there. Cullen and his posse confronted the mob at gunpoint, and took Jones back to Greene County.

20th century to present

Agriculture has continued to dominate the economy of this county. Now conducted on an industrial scale, it has reduced the need for farm workers. Unemployement is high in the rural county.

James Bevel, the main strategist and architect of the Civil Rights Movement, was buried in Ancestors Village Cemetery in Eutaw on December 29, 2008. In addition to his early work in the Nashville Student Movement and Mississippi movement, he initiated, planned, and directed the strategies for the 1963 Birmingham Children's Crusade, the 1965 Selma to Montgomery march, and the 1966 Chicago Open Housing Movement.

Eutaw is home to the Roman Catholic Convent of Our Lady of Consolata, the Consolata Sisters, a small monastery for nuns in West Alabama.[12] They are known throughout Greene County for their humanitarian efforts.

Geography

Eutaw is located east of the center of Greene County. U.S. Routes 11 and 43 pass through the center of town. The highways enter together from the northeast as Tuscaloosa Street; US 11 exits the city to the west as Boligee Street, while US 43 leaves to the south as Demopolis Highway. Alabama State Route 14 passes through the city as Greensboro Street to the southeast and Mesopotamia Street to the northwest. Interstates 20 and 59 run through the northwest corner of the city, with access from Exit 40 (Highway 14), 3 miles (5 km) northwest of the center of town. Tuscaloosa is 34 miles (55 km) to the northeast via Interstate 20/59, and Meridian, Mississippi, is 60 miles (97 km) to the southwest. Demopolis is 24 miles (39 km) south via US 43, Greensboro is 21 miles (34 km) to the southeast via Highway 14, and Aliceville is 27 miles (43 km) to the northwest via Highway 14.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, Eutaw has a total area of 12.0 square miles (31.1 km2), of which 11.9 square miles (30.9 km2) is land and 0.1 square miles (0.2 km2), or 0.63%, is water.[2] The center of town is 3 miles (5 km) west of the Black Warrior River, accessible to boats at Finches Ferry Public Use Area.

Climate

The climate in this area is characterized by hot, humid summers and generally mild to cool winters. According to the Köppen Climate Classification system, Eutaw has a humid subtropical climate, abbreviated "Cfa" on climate maps.[13]

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1850 | 2,000 | — | |

| 1880 | 1,101 | — | |

| 1890 | 1,115 | 1.3% | |

| 1900 | 884 | −20.7% | |

| 1910 | 1,001 | 13.2% | |

| 1920 | 1,359 | 35.8% | |

| 1930 | 1,721 | 26.6% | |

| 1940 | 1,895 | 10.1% | |

| 1950 | 2,348 | 23.9% | |

| 1960 | 2,784 | 18.6% | |

| 1970 | 2,805 | 0.8% | |

| 1980 | 2,444 | −12.9% | |

| 1990 | 2,281 | −6.7% | |

| 2000 | 1,878 | −17.7% | |

| 2010 | 2,934 | 56.2% | |

| Est. 2017 | 2,687 | [3] | −8.4% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[14] 2013 Estimate[15] | |||

As of the census[16] of 2000, there were 1,878 people, 778 households, and 504 families residing in the city. The population density was 411.1 people per square mile (158.7/km2). There were 899 housing units at an average density of 196.8 per square mile (76.0/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 33.01% White, 66.03% Black or African American, 0.27% Native American, 0.21% Asian, and 0.48% from two or more races. 0.37% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

There were 778 households out of which 24.7% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 39.5% were married couples living together, 21.5% had a female householder with no husband present, and 35.1% were non-families. 33.5% of all households were made up of individuals and 15.4% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.31 and the average family size was 2.95.

In the city, the population was spread out with 22.4% under the age of 18, 8.0% from 18 to 24, 22.6% from 25 to 44, 24.4% from 45 to 64, and 22.5% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 43 years. For every 100 females, there were 84.8 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 75.9 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $23,056, and the median income for a family was $32,946. Males had a median income of $30,284 versus $18,869 for females. The per capita income for the city was $14,573. About 24.7% of families and 28.9% of the population were below the poverty line, including 39.4% of those under age 18 and 22.5% of those age 65 or over.

2010 census

As of the census[17] of 2010, there were 2,934 people, 1,203 households, and 760 families residing in the city. The population density was 408.3 people per square mile (159.2/km2). There were 1,355 housing units at an average density of 294.6 per square mile (114.8/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 80.2% Black or African American, 18.1% White, 0.1% Native American, 0.4% Asian, and 0.6% from two or more races. 1.3% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

There were 1,203 households out of which 25.6% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 30.8% were married couples living together, 28.4% had a female householder with no husband present, and 36.8% were non-families. 34.2% of all households were made up of individuals and 15.5% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.40 and the average family size was 3.10.

In the city, the population was spread out with 25.8% under the age of 18, 9.2% from 18 to 24, 19.8% from 25 to 44, 28.4% from 45 to 64, and 16.8% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 39 years. For every 100 females, there were 82.7 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 77.5 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $29,196, and the median income for a family was $39,722. Males had a median income of $43,125 versus $28,077 for females. The per capita income for the city was $14,126. About 27.4% of families and 28.7% of the population were below the poverty line, including 38.7% of those under age 18 and 17.0% of those age 65 or over.

Arts and culture

The city hosts annual parades for Christmas, the Homecoming parade for surrounding schools in the area, and a parade for Martin Luther King, Jr. Day. Preceding the Christmas parade is the annual Christmas tree lighting by the city's mayor and a special Christmas program on that night, on the lawn of the Historic Courthouse Square. The National Day of Prayer is held on the historic courthouse square and so is Veteran's Day. Eutaw is known for its architecture and so the Historic Parade and viewing of homes is popular in this town and the event attracts many tourists.

Notable people

- Oliver H. Cross, U.S. Representative from Texas

- Edward deGraffenried, U.S. Representative from Alabama's 6th congressional district

- Cob Jarvis, basketball player and head basketball coach for the University of Mississippi

- Bill Lee, professional football player

- Matthew Leonard, Sergeant First Class who posthumously received the Medal of Honor and Purple Heart for his actions in the Vietnam War

- James McQueen, president of Sloss-Sheffield Steel & Iron Company

- Willie Powell, baseball pitcher in the Negro Leagues

In popular culture

Eutaw is the home town of the protagonist in the Old Crow Medicine Show song "Big Time in the Jungle," released in 2004. The band also released an album in 2001 entitled Eutaw. In addition, the town's name is referenced in the song "Don't Ride That Horse," among the other cities of Winnipeg, Joliet, Saskatoon, and Wawa. The 1981 horror film Jaws of Satan takes place in Eutaw.

See also

References

- ↑ "2017 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved Jul 7, 2018.

- 1 2 3 "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): Eutaw town, Alabama". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Retrieved October 28, 2016.

- 1 2 "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved March 24, 2018.

- ↑ http://www.lat34north.com/historicmarkersal/MarkerDetail.cfm?KeyID=32-09&MarkerTitle=Welcome%20To%20Eutaw%2C%20Alabama%3A%20A%20City%20of%20Progress

- ↑ National Park Service (2008-04-15). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- 1 2 Rogers, William Warren (2013-01-02). "The Boyd Incident: Black Belt Violence During Reconstruction". Civil War History. 21 (4): 309–329. doi:10.1353/cwh.1975.0009. ISSN 1533-6271.

- ↑ Davis, Susan Lawrence (1924). Authentic History, Ku Klux Klan, 1865-1877. p. 37.

- ↑ Newton, Michael (2004-01-01). The Encyclopedia of Unsolved Crimes. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 9780816069880.

- ↑ Hennessey, Melinda M. (1980). "Political Terrorism in the Black Belt: The Eutaw Riot". Alabama Review. 33: 35–48.

- ↑ Waldrep, Christopher (2011). Jury Discrimination: The Supreme Court, Public Opinion, and a Grassroots Fight for Racial Equality in Mississippi. U of Georgia P. p. 137. ISBN 9780820341941.

- ↑ [https://eji.org/sites/default/files/lynching-in-america-third-edition-summary.pdf Supplement: Lynchings by County (3rd edition), Lynching in America (2015, 3rd edition), p. Montgomery, Alabama: Equal Justice Initiative

- ↑

- ↑ Climate Summary for Eutaw, Alabama

- ↑ "U.S. Decennial Census". Census.gov. Archived from the original on May 12, 2015. Retrieved June 6, 2013.

- ↑ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2013". Retrieved June 3, 2014.

- ↑ "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on September 11, 2013. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ↑ "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on September 11, 2013. Retrieved 2015-07-24.

External links

- Davis, Stephen Duane II, and Alfred L. Brophy, "The Most Esteemed Act of My Life: Family, Property, Will, and Trust in the Antebellum South", an empirical study of probate in Greene County, Alabama