Environmental education

|

| Environment |

|---|

|

|

|

Environmental education (EE) refers to organized efforts to teach how natural environments function, and particularly, how human beings can manage behavior and ecosystems to live sustainably. It is a multi-disciplinary field integrating disciplines such as biology, chemistry, physics, ecology, earth science, atmospheric science, mathematics, and geography. The term often implies education within the school system, from primary to post-secondary. However, it sometimes includes all efforts to educate the public and other audiences, including print materials, websites, media campaigns, etc..

Environmental education (EE) is the teaching of individuals, and communities, in transitioning to a society that is knowledgeable of the environment and its associated problems, aware of the solutions to these problems, and motivated to solve them. The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) states that EE is vital in imparting an inherent respect for nature amongst society and in enhancing public environmental awareness. UNESCO emphasises the role of EE in safeguarding future global developments of societal quality of life (QOL), through the protection of the environment, eradication of poverty, minimization of inequalities and insurance of sustainable development (UNESCO, 2014a).

Focus

Environmental education focuses on:

1. Engaging with citizens of all demographics to;

2. Think critically, ethically, and creatively when evaluating environmental issues;

3. Make educated judgments about those environmental issues;

4. Develop skills and a commitment to act independently and collectively to sustain and enhance the environment; and,

5. To enhance their appreciation of the environment; resulting in positive environmental behavioural change (Bamberg & Moeser, 2007; Wals et al., 2014).

Related fields

Environmental education has crossover with multiple other disciplines. These fields of education complement environmental education yet have unique philosophies.

- Citizen Science (CS) aims to address both scientific and environmental outcomes through enlisting the public in the collection of data, through relatively simple protocols, generally from local habitats over long periods of time (Bonney et al., 2009).

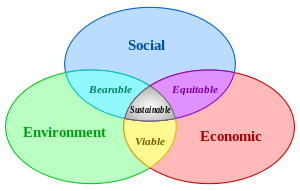

- Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) aims to reorient education to empower individuals to make informed decisions for environmental integrity, social justice, and economic viability for both present and future generations, whilst respecting cultural diversities (UNESCO, 2014b).

- Climate Change Education (CCE) aims in enhancing the public's understanding of climate change, its consequences, and its problems, and to prepare current and future generations to limit the magnitude of climate change and to respond to its challenges (Beatty, 2012). Specifically, CCE needs to help learners develop knowledge, skills and values and action to engage and learn about the causes, impact and management of climate change [1](Chang, 2014).

- Science Education (SE) focuses primarily on teaching knowledge and skills, to develop innovative thought in society (Wals et al., 2014).

- Outdoor Education (OE) relies on the assumption that learning experiences outdoors in ‘nature’ foster an appreciation of nature, resulting in pro-environmental awareness and action (Clarke & Mcphie,2014). Outdoor education means learning "in" and "for" the outdoors.

- Experiential education (ExE) is a process through which a learner constructs knowledge, skill, and value from direct experiences" (AEE, 2002, p. 5) Experiential education can be viewed as both a process and method to deliver the ideas and skills associated with environmental education (ERIC, 2002).

- Garden-based learning (GBL) is an instructional strategy that utilizes the garden as a teaching tool. It encompasses programs, activities and projects in which the garden is the foundation for integrated learning, in and across disciplines, through active, engaging, real-world experiences that have personal meaning for children, youth, adults and communities in an informal outside learning setting.

- Inquiry-based Science (IBS) is an active open style of teaching in which students follow scientific steps in a similar manner as scientists to study some problem (Walker 2015). Often used in biological and environmental settings.

While each of these educational fields has their own objectives, there are points where they overlap with the intentions and philosophy of environmental education.

History

The roots of environmental education can be traced back as early as the 18th century when Jean-Jacques Rousseau stressed the importance of an education that focuses on the environment in Emile: or, On Education. Several decades later, Louis Agassiz, a Swiss-born naturalist, echoed Rousseau’s philosophy as he encouraged students to “Study nature, not books.”[2] These two influential scholars helped lay the foundation for a concrete environmental education program, known as nature study, which took place in the late 19th century and early 20th century.

The nature study movement used fables and moral lessons to help students develop an appreciation of nature and embrace the natural world.[3] Anna Botsford Comstock, the head of the Department of Nature Study at Cornell University, was a prominent figure in the nature study movement and wrote the Handbook for Nature Study in 1911, which used nature to educate children on cultural values.[3] Comstock and the other leaders of the movement, such as Liberty Hyde Bailey, helped Nature Study garner tremendous amounts of support from community leaders, teachers, and scientists and change the science curriculum for children across the United States.

A new type of environmental education, Conservation Education, emerged as a result of the Great Depression and Dust Bowl during the 1920s and 1930s. Conservation Education dealt with the natural world in a drastically different way from Nature Study because it focused on rigorous scientific training rather than natural history.[3] Conservation Education was a major scientific management and planning tool that helped solve social, economic, and environmental problems during this time period.

The modern environmental education movement, which gained significant momentum in the late 1960s and early 1970s, stems from Nature Study and Conservation Education. During this time period, many events – such as Civil Rights, the Vietnam War, and the Cold War – placed Americans at odds with one another and the U.S. government. However, as more people began to fear the fallout from radiation, the chemical pesticides mentioned in Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, and the significant amounts of air pollution and waste, the public’s concern for their health and the health of their natural environment led to a unifying phenomenon known as environmentalism. Environmental education was born of the realization that solving complex local and global problems cannot be accomplished by politicians and experts alone, but requires "the support and active participation of an informed public in their various roles as consumers, voters, employers, and business and community leaders" [4]

One of the first articles about environmental education as a new movement appeared in the Phi Delta Kappan in 1969, authored by James A. Swan.[5] A definition of "Environmental Education" first appeared in The Journal of Environmental Education in 1969, authored by William B. Stapp.[6] Stapp later went on to become the first Director of Environmental Education for UNESCO, and then the Global Rivers International Network.

Ultimately, the first Earth Day on April 22, 1970 – a national teach-in about environmental problems – paved the way for the modern environmental education movement. Later that same year, President Nixon passed the National Environmental Education Act, which was intended to incorporate environmental education into K-12 schools.[7] Then, in 1971, the National Association for Environmental Education (now known as the North American Association for Environmental Education) was created to improve environmental literacy by providing resources to teachers and promoting environmental education programs.

Internationally, environmental education gained recognition when the UN Conference on the Human Environment held in Stockholm, Sweden, in 1972, declared environmental education must be used as a tool to address global environmental problems. The United Nations Education Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) and United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) created three major declarations that have guided the course of environmental education.

Stockholm Declaration

June 5–16, 1972 - The Declaration of the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment. The document was made up of 7 proclamations and 26 principles "to inspire and guide the peoples of the world in the preservation and enhancement of the human environment."

Belgrade Charter

October 13–22, 1975 - The Belgrade Charter[8] was the outcome of the International Workshop on Environmental Education held in Belgrade, Jugoslavia (now Serbia). The Belgrade Charter was built upon the Stockholm Declaration and adds goals, objectives, and guiding principles of environmental education programs. It defines an audience for environmental education, which includes the general public.

Tbilisi Declaration

October 14–26, 1977 - The Tbilisi Declaration "noted the unanimous accord in the important role of environmental education in the preservation and improvement of the world's environment, as well as in the sound and balanced development of the world's communities." The Tbilisi Declaration updated and clarified The Stockholm Declaration and The Belgrade Charter by including new goals, objectives, characteristics, and guiding principles of environmental education.

Later that decade, in 1977, the Intergovernmental Conference on Environmental Education in Tbilisi, Georgia emphasized the role of Environmental Education in preserving and improving the global environment and sought to provide the framework and guidelines for environmental education. The Conference laid out the role, objectives, and characteristics of environmental education, and provided several goals and principles for environmental education.

About

Environmental education has been considered an additional or elective subject in much of traditional K-12 curriculum. At the elementary school level, environmental education can take the form of science enrichment curriculum, natural history field trips, community service projects, and participation in outdoor science schools. EE policies assist schools and organizations in developing and improving environmental education programs that provide citizens with an in-depth understanding of the environment. School related EE policies focus on three main components: curricula, green facilities, and training.

Schools can integrate environmental education into their curricula with sufficient funding from EE policies. This approach – known as using the “environment as an integrating context” for learning – uses the local environment as a framework for teaching state and district education standards. In addition to funding environmental curricula in the classroom, environmental education policies allot the financial resources for hands-on, outdoor learning. These activities and lessons help address and mitigate "nature deficit disorder", as well as encourage healthier lifestyles.

Green schools, or green facility promotion, are another main component of environmental education policies. Greening school facilities cost, on average, a little less than 2 percent more than creating a traditional school, but payback from these energy efficient buildings occur within only a few years.[9] Environmental education policies help reduce the relatively small burden of the initial start-up costs for green schools. Green school policies also provide grants for modernization, renovation, or repair of older school facilities. Additionally, healthy food options are also a central aspect of green schools. These policies specifically focus on bringing freshly prepared food, made from high-quality, locally grown ingredients into schools.

In secondary school, environmental curriculum can be a focused subject within the sciences or is a part of student interest groups or clubs. At the undergraduate and graduate level, it can be considered its own field within education, environmental studies, environmental science and policy, ecology, or human/cultural ecology programs.

Environmental education is not restricted to in-class lesson plans. Children can learn about the environment in many ways. Experiential lessons in the school yard, field trips to national parks, after-school green clubs, and school-wide sustainability projects help make the environment an easily accessible topic. Furthermore, celebration of Earth Day or participation in EE week (run through the National Environmental Education Foundation) can help further environmental education. Effective programs promote a holistic approach and lead by example, using sustainable practices in the school to encourage students and parents to bring environmental education into their home.

The final aspect of environmental education policies involves training individuals to thrive in a sustainable society. In addition to building a strong relationship with nature, citizens must have the skills and knowledge to succeed in a 21st-century workforce. Thus, environmental education policies fund both teacher training and worker training initiatives. Teachers train to effectively teach and incorporate environmental studies. On the other hand, the current workforce must be trained or re-trained so they can adapt to the new green economy. Environmental education policies that fund training programs are critical to educating citizens to prosper in a sustainable society.

In the United States

Following the 1970s, non-governmental organizations that focused on environmental education continued to form and grow, the number of teachers implementing environmental education in their classrooms increased, and the movement gained stronger political backing. A critical move forward came when the United States Congress passed the National Environmental Education Act of 1990, which placed the Office of Environmental Education in the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and allowed the EPA to create environmental education initiatives at the federal level.[7] Through the EPA Environmental Education (EE) Grant Program, public schools, communities agencies, and NGO’s are eligible to receive federal funding for local educational projects that reflect the EPA’s priorities: air quality, water quality, chemical safety, and public participation among the communities.[10]

In the United States some of the antecedents of Environmental Education were Nature Studies, Conservation Education and School Camping. Nature studies integrated academic approach with outdoor exploration (Roth, 1978). Conservation Education brought awareness to the misuse of natural resources. George Perkins Marsh discoursed on humanity’s integral part of the natural world. The governmental agencies like the U.S. Forest Service and the EPA were also pushing a conservation agenda. Conservation ideals still guide environmental education today. School Camping was exposure to the environment and use of resources outside of the classroom for educational purposes. The legacies of these antecedents are still present in the evolving arena of environmental education.

Obstacles

A study of Ontario teachers explored obstacles to environmental education.[11] Through an internet-based survey questionnaire, 300 K-12 teachers from Ontario, Canada responded. Based on the results of the survey, the most significant challenges identified by the sample of Ontario teachers include over-crowded curriculum, lack of resources, low priority of environmental education in schools, limited access to the outdoors, student apathy to environmental issues, and the controversial nature of sociopolitical action.[11]

An influential article by Stevenson (2007) outlines conflicting goals of environmental education and traditional schooling.[12] According to Stevenson (2007), the recent critical and action orientation of environmental education creates a challenging task for schools. Contemporary environmental education strives to transform values that underlie decision making from ones that aid environmental (and human) degradation to those that support a sustainable planet.[13] This contrasts with the traditional purpose of schools of conserving the existing social order by reproducing the norms and values that currently dominate environmental decision making.[12] Confronting this contradiction is a major challenge to environmental education teachers.

Additionally, the dominant narrative that all environmental educators have an agenda can present difficulties in expanding reach. It is said that an environmental educator is one "who uses information and educational processes to help people analyze the merits of the many and varied points of view usually present on a given environmental issues."[14] Greater efforts must be taken to train educators on the importance of staying within the profession's substantive structure, and in informing the general public on the profession's intention to empower fully informed decision making.

Another obstacle facing the implementation of environmental education lies the quality of education itself. Charles Sayan, the executive director of the Ocean Conservation Society, represents alternate views and critiques on environmental education in his new book The Failure of Environmental Education (And How We Can Fix It). In a Yale Environment 360 interview, Sayan discusses his book and outlines several flaws within environmental education, particularly its failed efforts to “reach its potential in fighting climate change, biodiversity loss, and environmental degradation”.[15] He believes that environmental education is not “keeping pace with environmental degradation” and encourages structural reform by increasing student engagement as well as improving relevance of information.[16] These same critiques are discussed in Stewart Hudson’s BioScience paper, “Challenges for Environmental Education: Issues and Ideas for the 21st Century”.[17]

Movement

A movement that has progressed since the relatively recent founding (1960s) of environmental education in industrial societies has transported the participant from nature appreciation and awareness to education for an ecologically sustainable future. This trend may be viewed as a microcosm of how many environmental education programs seek to first engage participants through developing a sense of nature appreciation which then translates into actions that affect conservation and sustainability.

Programs range from New York to California, including Life Lab at University of California, Santa Cruz, as well as Cornell University in Ithaca.

Environmental Education in the Global South

Environmentalism has also began to make waves in the development of the global South, as the “First World” takes on the responsibility of helping developing countries to combat environmental issues produced and prolonged by conditions of poverty. Unique to environmental education in the Global South is its particular focus on sustainable development. This goal has been a part of international agenda since the 1900’s, with the United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organizations (UNESCO) and the Earth Council Alliance (ECA) at the forefront of pursuing sustainable development in the south.

The 1977 Tbilisi intergovernmental conference played a key role in the development of outcome of the conference was the Tbilisi Declaration, a unanimous accord which “constitutes the framework, principles, and guidelines for environmental education at all levels—local, national, regional, and international—and for all age groups both inside and outside the formal school system” recommended as a criteria for implementing environmental education. The Declaration was established with the intention of increasing environmental stewardship, awareness and behavior, which paved the way for the rise of modern environmental education.

After the 1992 Rio Earth Summit, over 80 National Councils for Sustainable Development in developing countries were created between 1992-1998 to aid in compliance of international sustainability goals and encourage “creative solutions”.

In 1993, the Earth Council Alliance released the Treaty on environmental education for sustainable societies and global responsibility, sparking discourse on environmental education. The Treaty, in 65 statements, outlines the role of environmental education in facilitating sustainable development through all aspects of democratized participation and provides a methodology for the Treaty’s signatories. It has been instrumentally utilized in expanding the field towards the global South, wherein the discourse of “environmental education for sustainable development” recognizes a need to include human population dynamics in EE and emphasizes “aspects related to contemporary economic realities and by placing greater emphasis on concerns for planetary solidarity”. Even as a necessary tool for the proliferation of environmental stewardship, environmental education implemented in the South varies and addresses environmental issues in relation to their impact different communities and specific community needs. Whereas in the developed global North where the environmentalist sentiments are centered around conservation without taking into consideration “the needs of people living within communities”, the global South must push forth a conservation agenda that parallels with social, economic, and political development. The role of environmental education in the South is centered around potential economic growth in development projects, as explicitly stated by the UNESCO, to apply environmental education for sustainable development through a "creative and effective use of human potential and all forms of capital to ensure rapid and more equitable economic growth, with minimal impact on the environment".

Moving into the 21st century, EE was furthered by United Nations as a part of the 2000 Millennium Development Goals to improve the planet by 2015. The MDGs included global efforts to end extreme poverty, work towards gender equality, access to education, and sustainable development to name a few. Although the MDGs produced great outcomes, its objectives were not met, and MDGs were soon were soon replaced by Sustainable Development Goals. A “universal call to action to end poverty, protect the planet and ensure that all people enjoy peace and prosperity”, SDGs became the new face of global priorities.[18] These new goals incorporated objectives from MDGs yet incorporated a necessary environmental framework to “address key systemic barriers to sustainable development such as inequality, unsustainable consumption patterns, weak institutional capacity and environmental degradation that the MDGs neglected”.[19]

Trends

One of the current trends within environmental education seeks to move from an approach of ideology and activism to one that allows students to make informed decisions and take action based on experience as well as data. Within this process, environmental curricula have progressively been integrated into governmental education standards. Some environmental educators find this movement distressing and a move away from the original political and activist approach to environmental education while others find this approach more valid and accessible.[20] Regardless, many educational institutions are encouraging students to take an active role in environmental education and stewardship at their institutions. They know that "to be successful, greening initiatives require both grassroots support from the student body and top down support from high-level campus administrators."[21]

See also

- The Amazonia Conference

- Arts-based environmental education

- Citizen Science

- Climate Change

- Earth Expeditions

- Education for Sustainable Development

- Environmental adult education

- Environmental psychology

- Environmental science

- Environmental studies

- Expeditionary education

- Fourth International Conference on Environmental Education

- Global education

- Go Green Initiative (GGI)

- Learnscapes

- List of environmental degrees

- List of environmental education institutions

- Nature centers

- Network of Conservation Educators and Practitioners

- Outdoor education

- Quality of life

- Science Education

- Science, Technology, Society and Environment Education

- UNESCO

References

Notes

- ↑ Chang, C. H. (2014). Climate change education: Knowing, doing and being. Rutledge.

- ↑ Berkeley.edu

- 1 2 3 Bill Cronon, WilliamCronon.net Archived 2010-11-18 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Canadian Environmental Grantmakers Network. 2006. "Environmental Education in Canada: An overview for grantmakers," Toronto: ON. http://www.cegn.org/english/home/documents/EEBrief_Eng.pdf, p. 2

- ↑ Swan, J.A. (1969). "The challenge of environmental education". Phi Delta Kappan. 51: 26–28.

- ↑ Stapp, W.B.; et al. (1969). "The Concept of Environmental Education" (PDF). The Journal of Environmental Education. 1 (1): 30–31.

- 1 2 EElink.net Archived 2010-06-11 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ The Belgrade Charter, Adopted by the UNESCO-UNEP International Environmental Workshop, October 13–22, 1975. http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0001/000177/017772eb.pdf accessed 3 March 2011

- ↑ Earthday.net

- ↑ "Frequently Asked Questions about the Environmental Education Grants Program". 2013-12-12.

- 1 2 Tan, M.; Pedretti, E. (2010). "Negotiating the complexities of environmental education: A study of Ontario teachers". Canadian Journal of Science, Mathematics and Technology Education. 10 (1): 61–78. doi:10.1080/14926150903574320.

- 1 2 Stevenson, R. B. (2007). "Schooling and environmental education: Contradictions in purpose and practice". Environmental Education Research. 13 (2): 139–153. doi:10.1080/13504620701295726.

- ↑ Tanner, R.T. 1974. "Ecology, environment and education," Lincoln, NE, Professional Educators Publications

- ↑ Hug, J. (1977). Two hats. In H. R. Hungerford, W. J. Bluhm, T. L. Volk, & J. M. Ramsey (Eds.), Essential Readings in Environmental Education (pp. 47). Champaign, IL: Stipes Publishing

- ↑ The Failure of Environmental Education (And How We Can Fix It).

- ↑ Nijhuis, Michelle (2011). "Green Failure: What's Wrong With Environmental Education? - Yale E360". e360.yale.edu. Retrieved 2018-03-17.

- ↑ HUDSON, STEWART J. (2001-04-01). "Challenges for Environmental Education: Issues and Ideas for the 21st Century". BioScience. 51 (4): 283. doi:10.1641/0006-3568(2001)051[0283:cfeeia]2.0.co;2. ISSN 0006-3568.

- ↑ "Sustainable Development Goals". UNDP. Retrieved 2018-05-12.

- ↑ Simkiss, D. (2015-07-24). "The Millennium Development Goals are Dead; Long Live the Sustainable Development Goals". Journal of Tropical Pediatrics. 61 (4): 235–237. doi:10.1093/tropej/fmv048. ISSN 0142-6338. PMID 26209862.

- ↑ Blumstein, Daniel T; Saylan, Charlie (2007-04-17). "The Failure of Environmental Education (and How We Can Fix It)". PLoS Biology. 5 (5): e120. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0050120. ISSN 1545-7885. PMC 1847843. PMID 17439304.

- ↑ Reynolds, Heather; Brondizio, Eduardo; Robinson, Jennifer; Karpa, John; Gross, Briana (2010-01-11). Teaching Environmental Literacy. Indiana University Press. p. 178. ISBN 9780253221506.

Bibliography

- Gruenewald, D.A. (2004). "A Foucauldian analysis of environmental education: toward the socioecological challenge of the Earth Charter". Curriculum Inquiry. 34 (1): 71–107. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.470.5449. doi:10.1111/j.1467-873x.2004.00281.x.

- Hoelscher, David W. 2009. "Cultivating the Ecological Conscience: Smith, Orr, and Bowers on Ecological Education." M.A. thesis, University of North Texas. https://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc12133/m1/

- Kyburz-Graber, R.; Hofer, K.; Wolfensberger, B. (2006). "Studies on a socio-ecological approach to environmental education – a contribution to a critical position in the education for sustainable development discourse". Environmental Education Research. 12 (1): 101–114. doi:10.1080/13504620500527840.

- Lieberman, G.A. & L.L. Hoody. 1998. "Closing the Achievement Gap: Using the Environment as an Integrating Context for Learning." State Education and Environment Roundtable, Poway, CA.

- Lieberman, Gerald A. 2013. Education and the Environment: Creating Standards-Based Programs in Schools and Districts. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

- Malone, K (1999). "Environmental education researchers as environmental activists". Environmental Education Research. 5 (2): 163–177. doi:10.1080/1350462990050203.

- Palmer, J.A, 1998. Environmental Education in the 21st Century: Theory, Practice, Progress, and Promise. Routledge.

- Roth, Charles E. 1978. "Off the Merry-Go-Round and on to the Escalator". pp. 12–23 in From Ought to Action in Environmental Education, ed. William B. Stapp. Columbus, OH: SMEAC Information Reference Center. Ed 159 046.

- "Overhauling environmental education". Science. 276 (5311): 361. 1997. doi:10.1126/science.276.5311.361d.

- Smyth, J.C. (2006). "Environment and education: a view of a changing scene". Environmental Education Research. 12 (3–4): 247–264. doi:10.1080/13504620600942642.

- Stohr, W (2013). "Coloring a Green Generation: The Law and Policy of Nationally-Mandated Environmental Education and Social Value Formation at the Primary and Secondary Academic Levels". The Journal of Law and Education. 42 (1): 1–110.

- Bamberg, S.; Moeser, G. (2007). "Twenty years after Hines, Hungerford, and Tomera: A new meta-analysis of psycho-social determinants of pro-environmental behaviour". Journal of Environmental Psychology. 27 (1): 14–25. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2006.12.002.

- Beatty. A., 2012. Climate Change Education. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press

- Bonney, R.; et al. (2009). ", 2009. Citizen Science: A Developing Tool for Expanding Science Knowledge and Scientific Literacy". BioScience. 59 (11): 977–984. doi:10.1525/bio.2009.59.11.9. JSTOR 10.1525/bio.2009.59.11.9.

Clarke, D.A.G.; Mcphie (2014). "Becoming animate in education: immanent materiality and outdoor learning for sustainability". Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning. 14 (3): 198–216. doi:10.1080/14729679.2014.919866.

- Education Resources Information Centre (ERIC), 2002. Outdoor, Experiential, and Environmental Education: Converging or Diverging Approaches? [pdf]. ERIC Development Team. Available at: <http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED467713.pdf>

- Pooley, J.A.; O'Connor, M. (2000). "Environmental education and attitudes - Emotions and beliefs are what is needed". Environment and Behavior. 32 (5): 711–723. doi:10.1177/0013916500325007.

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization., 2014a. Ecological Sciences for Sustainable Development. [online] Available at: <http://www.unesco.org/new/en/natural-sciences/environment/ecological-sciences/capacity-building-and-partnerships/educational-materials/>

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization., 2014b. Shaping the Future We Want: UN Decade of Education for Sustainable Development. [pdf] Paris: UNESCO. Available at: < http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0023/002301/230171e.pdf>

- Wals, A. E.; et al. (2014). ", 2014. Convergence Between Science and Environmental Education" (PDF). Science. 344 (6184): 583–4. doi:10.1126/science.1250515. PMID 24812386.

- Walker. M. D. 2015. Teaching Inquiry-based Science. Sicklebrook Publishing. ISBN 978-1312955622

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Environmental education. |

- Belgrade Charter

- Council for Environmental Education (CEE)

- Earth Day Network

- Environmental Education Linked Network

- Mobile Environmental Education Projects (MEEPs)

- National Environmental Education Foundation

- State Education and Environment Roundtable (SEER)

- United Nations Environmental Education Programme (UNEP)