Singer Presents...Elvis

| Singer Presents...Elvis | |

|---|---|

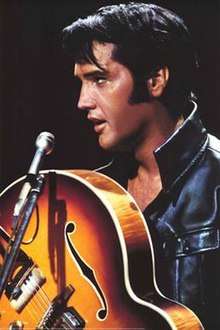

Publicity poster for the special, seen in Singer stores | |

| Also known as | '68 Comeback Special |

| Written by |

Chris Bearde Allen Blye |

| Directed by | Steve Binder |

| Starring | Elvis Presley |

| Composer(s) | Billy Goldenberg |

| Country of origin | United States |

| Original language(s) | English |

| Production | |

| Producer(s) |

Steve Binder Bones Howe |

| Production location(s) | Burbank, California |

| Editor(s) |

Wayne Kenworthy Armond Poitras |

| Camera setup | Multi-camera |

| Running time | 50 minutes |

| Distributor |

NBC (TV Special) Sony Music Entertainment (DVD releases) |

| Release | |

| Original network | NBC |

| Original release | December 3, 1968 |

Singer Presents...Elvis (commonly referred to as the 68 Comeback Special) is a television special starring singer Elvis Presley, aired by the National Broadcasting Company (NBC) on December 3, 1968. It marked Presley's return to live performance after seven years during which his career was centered in the movie business. Presley was unhappy with his distance from musical trends of the time, and the low-quality movie productions he was involved in.

Initially planned as a Christmas special by the network, and Presley's manager Colonel Tom Parker, producer Bob Finkel transformed the idea. He hired director Steve Binder to update Presley's sound, and to create a special that would be current and appeal to a younger audience. The special garnered good reviews when it aired, topped the Nielsen television ratings for the week, and was the most watched show of the season. Later known as the "Comeback Special", it re-launched Presley's singing career and his return to live performance.

Background

After he returned from serving in the United States Army, Elvis Presley enjoyed success with his album releases. G.I. Blues, the soundtrack album to his movie G.I. Blues topped both the Billboard Pop Albums chart and the UK Albums Chart in October 1960. On March 25, 1961, Presley played a concert in Hawaii to benefit the construction of the USS Arizona Memorial. It would be his last public performance for seven years. Presley's next number one album on the Billboard Pop Albums chart was Something for Everybody released in June 1961.[1]

His manager, Colonel Tom Parker, decided to shift the focus of Presley's career to movie making, and stopped him touring. The films were low-budget, formulaic comedies. Their releases were successful at the box office, while the resulting albums sold well. Presley attempted to move into more dramatic roles, trying to reduce the prominence of musical numbers to center on his acting with Flaming Star and Wild in the Country.[2] Both releases flopped, and by 1964 Parker decided to limit all recordings exclusively to movie soundtracks. Parker then set the Presley formula: the films would promote album releases, while album releases would promote the films.[3]

To further cheapen the process, producer Hal Wallis decided to shorten filming schedules, almost abandoning rehearsals and retakes. He stopped shooting on location and centered all his activities in the studio. Wallis also resorted to smaller studios, dropping experienced crews. Scenes were limited to long shots, medium shots and close-ups to speed up the process. Meanwhile, studio recordings also declined in quality, with musicians often recording their parts before Presley himself. By 1965, Presley was paid $750,000 and fifty percent of the film profits, for his appearance in Tickle Me. This payment made up most of the film's budget. Since the studio, Allied Artists, had money problems, Parker decided to put unused songs from other studio sessions on the soundtrack and instructed the studio to work them into the film. The tight production worked, and on its release, it was a box office success.[4]

Girl Happy (1965) marked the first failure to date of this approach. The score was Presley's most unsuccessful release, while the film barely grossed $2 million.[5] Despite the success of Parker's model, Presley soon grew discontented with the quality of his work. With the passage of time, he considered his connection to the music business was being weakened, and he felt depressed and alienated as the quality of his films deteriorated.[6] During a five-year span—1964 through 1968—Presley had only one top-ten hit: "Crying in the Chapel" (1965), a gospel number recorded in 1960. [7] While the 1964 release Viva Las Vegas enjoyed success, the follow-up films saw a progressive decline. By 1967, the difficulty of negotiating with Parker, and the poor performance of the films, led Wallis opt out of his contract with Presley.[8]

NBC deal

In October 1967, Parker approached West Coast vice president of the NBC, Tom Sarnoff. Parker proposed a deal for a Christmas television special. The US$1,250,000 package included the financing of a motion picture (for US$850,000), its soundtrack (for US$25,000), the television special (US$250,000) and US$125,000 reserved for the costs related to a re-run.[9] The special was to be included in the feature Singer Presents..., sponsored by the Singer Corporation.[10]

Presley's initial reaction to the special was negative. He felt it was another scheme by Parker and was angered by the idea of singing Christmas carols on national television. [11] His opinion started to change after he began talks with the special's producer, Bob Finkel. Finkel was able to persuade Singer, NBC and Parker to alter the show's original concept. He obtained Parker's approval on agreeing to his terms: the show was to be centered only on Presley, while enough material for a soundtrack album and a Christmas single was to be recorded. Presley's enthusiasm for the project grew, and he assured Finkel he was ready to perform new material, different than anything he had previously done. He had no interest in Parker's opinion of the project.[12]

To reflect the new direction Presley's career was intended to take, Finkel thought of director Steve Binder. Binder had directed the concert film T.A.M.I. Show and worked for NBC on Hullabaloo, as well as for the Petula Clark television special aired by the network. Finkel felt the addition of Binder would refresh Presley's image, and the director would be able to re-introduce him to the new audiences. Initially reluctant to direct the special, Binder was convinced by his associate, Bones Howe. Howe met Presley during the 1950s, while he worked at Radio Recorders as an audio engineer. He insisted on working with Presley, since he thought Binder had similar production methods. A meeting was arranged with Parker, during which Presley's manager assured the team they would be given full creative control, while he stressed that the publishing rights to the material had to be under Presley's name. Howe and Binder met with Presley later that week, and told the singer they would prepare all the details of the special, and have them ready by the time he returned from his vacation in Hawaii.[13]

Production

Binder and Howe then hired the production crew, repeating their collaboration with various people they had used for past specials. Billy Goldenberg was assigned as the musical director, while the Presley camp chose Billy Strange as the arranger. Chris Bearde and Allan Blye were hired as the writers, and Bill Belew for the costume design. Bearde and Blye proposed an idea based on Maurice Maeterlinck's The Blue Bird. It was intended to portray Presley's career through his songs, with its climax coming together in the special. Singer's representative, Alfred Discipio, approved the idea, as did Parker. The snippets of the story were connected by a number covering Jerry Reed's "Guitar Man". [14] An informal segment was planned featuring Presley talking to members of his entourage in a scripted conversation that was to show him as self-deprecating while discussing his movie performances. A gospel number would be added, as well as a live stand-up performance. Then the Christmas song, requested by Parker, would be played; the special would close with a spoken statement by Presley. Binder wanted him to express his feelings about the current situation in the US. Presley had been moved by the recent assassinations of Senator Robert Kennedy and Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr.. King's assassination deeply touched Presley, who felt that his killing, having taken place in Memphis, Tennessee, "only confirmed everyone's worst feelings about the south".[15]

By June 3, Presley returned to Hollywood to start the rehearsals that would last for two weeks. At the time, Howe insisted on the possibility of a soundtrack for the album, with the idea of collecting royalties from it as the producer. NBC saw Howe's attitude as a potential danger to the special and ordered Binder to remove him from the staff. The production was further complicated when Goldberg complained to Binder about Strange not turning in any musical arrangements for the special with only two weeks before the end of pre-production. Binder talked to Strange, who left the special alleging he was too busy with other projects. A week before the end of rehearsals, the production team allowed Bones to return as producer and engineer.[16]

On June 17, the team moved to the NBC studios in Burbank, California. Goldenberg asked producer Finkel to remove Presley's large entourage from the production area, complaining that his companions interfered with the creative process. Presley started to work with choreographer Lance LeGault on the planned numbers, and Belew started to work with the costumes.[17]

Binder and Howe developed the concept of the informal section of the show after seeing Presley interacting with his entourage while playing music during breaks. Binder planned to shoot the segment in the locker room to give the public a sense of how Presley's music was developed in an intimate setting. Parker opposed this concept. Binder settled for a sit-down concert, set in a small stage that resembled a boxing ring. He called Presley's first backup musicians, Scotty Moore and DJ Fontana, to accentuate the nature of the singer's musical origins. They were also joined by members of Presley's entourage Charlie Hodge and Alan Fortas. The scripted part was cancelled, but the writers gave Presley a list of topics to discuss between songs. The topics included mentions of his early career, his Hollywood years and the current music business. [14]

On June 20, Presley started the recording process at United Western Recorders. Bones arranged for rhythm section, session musicians from Los Angeles. The band was composed of drummer Hal Blaine and guitarists Mike Deasy and Tommy Tedesco. Part of the string and brass sections of the NBC orchestra were also enlisted.[18] All the material, except the live sections of the show, was pre-recorded by Presley. It was to be blended with live vocals during the production numbers, which were taped on June 27.[19]

On the same day, Presley taped the first sit-down show. Colonel Parker had told the NBC team he would take care of the ticket distribution. He assured them he would fly fans from different parts of the country to fill the studio. By the day of the show, however, Parker had not distributed the tickets, and only a few people were in line to see the taping. Binder and Finkel invited people from a restaurant across the street and put an announcement on a local radio station to round up an audience for the taping. Presley was nervous at the beginning of the first hour-long set. Binder had to convince him to take the stage, but once there, Presley was comfortable. He performed his songs and traded jokes with his companions as the session progressed. By the end of the first show, Belew had to carefully remove the sweat-soaked leather suit that was now stuck to Presley's skin. To get it ready for the next show, he had to hand wash it. He was helped by the rest of the costume crew who used hairdryers to hasten the process. [20] For the 8:00 PM show, individual rubber mats were placed at the feet of Presley and the band. During the first show, the producers were concerned about the effects of the toe tapping on the recordings.[21] The second show found Presley relaxed and running through the set list with ease.[20]

On June 29, Presley recorded both stand-up sessions. As with the first two shows, the cameras that shot Presley from different angles did not have individual taping machines. The director chose the camera angle he desired, and the cameras fed either of the two available taping machines.[22] The arrangements of the songs for the stand-up shows were fast-paced — Presley accompanied them with shakes, gyrations and facial expressions that he emphasized with fist gestures and knee-drops.[23]

For the show's closer, Binder decided to replace the spoken statement with a song. He instructed Goldenberg and lyricist Walter Earl Brown to write a song that reflected Presley and his beliefs. Brown wrote the song the same night. Binder sent it to Parker, who still thought the show closer was "I'll Be Home for Christmas". After Parker's negative response to the song, Binder bypassed him, and played the song for Presley. After hearing it three times, Presley was convinced to record it. Seeing Presley's determination, Parker demanded 100 percent of the publishing rights. Goldenberg removed his name from the publishing sheet, and told Parker that Brown wrote the song.[24] For this number, Presley wore a three-piece white suit designed by Belew. A large sign in red letters that read ELVIS was placed on the black background, while Presley performed the song with a hand-held microphone. After finishing the song, Presley closed the special by saying "Good night. Thank you very much.”

Release and reception

The special's final running time was 50 minutes, edited from four hours of taping. Presley was satisfied with the result.[25] Singer Presents...Elvis aired on December 3, 1968, at 9:00 PM Eastern Time.[26] It placed first in the Nielsen television ratings for the week ending on December 8, 1968, displacing Rowan & Martin's Laugh-In which dropped to the second position.[27] 42 percent of the total television audience viewed it, making it the most watched show of the season.[28] The special's soundtrack was released shortly after. It reached number eight on Billboard's Top LP's chart,[29] and by July 1969, it was certified gold.[30]

The New York Times opened its review describing Presley's breakthrough, and his influence on the musicians of the time. It observed that on this special, he was "rather conservative" compared to his new peers. Critic Robert Shelton called the mixture of Presley's looks and his audience a "reductio ad absurdum". He stressed the singer's impact on music, but felt the program showed "(a) charismatic performer (who) was at his best ten years ago, but hasn't lost his grip on the best music he had to offer then".[31]

The review by the Newspaper Enterprise Association published in the El Paso Herald-Post said the special "reveals a new Elvis Presley who has never before been seen," and is indicative "of a new, a more mature" Presley.[32] The Daily Tar Heel published a favorable review of the special, remarking on the change since the singer's heyday, declaring: "Elvis still has magic ... Magic in his tremendously moving voice, and magic in the memories of what it used to be."[33]

The Associated Press wrote of the performance: "Elvis Presley returns with his caged-animal energy," and stated "his power to rock an audience is still there".[34] The Ottawa Journal praised the singer, while it noted that he delivered a calmer stage presence which "no longer need(ed) the sensationalism that spiraled him to the top". The reviewer lamented the editing of the program, and the selection of the "cage-like stage" in which Presley appeared to pace — "not at ease".[35]

Jon Landau of Eye magazine remarked, "There is something magical about watching a man who has lost himself find his way back home. He sang with the kind of power people no longer expect of rock 'n' roll singers. He moved his body with a lack of pretension and effort that must have made Jim Morrison green with envy."[36] Dave Marsh called the performance one of "emotional grandeur and historical resonance".[37]

Aftermath

After the taping of the first sit-down session, Presley called Parker to his dressing room, and told him he wanted to return to touring. During a press conference, Parker announced that Presley would soon embark on a "Comeback Tour". Parker's choice of words angered Presley, who felt he was being labeled a "has-been". Presley was also interested in further collaboration with Binder, but Parker avoided it.[25]

By January 1969, propelled by the success of the special, and his renewed enthusiasm, Presley started his return to recording non-soundtrack albums with producer Chips Moman. Recorded at American Sound Studio with the house band known as "The Memphis Boys", the resulting country-soul album was titled From Elvis in Memphis.[38] The non-album cut "Suspicious Minds" became the last chart-topper of Presley's career, and one of his signature songs.[39] In July 1969, Rolling Stone featured a picture of Presley, taken during one of the show's stand-up segments, on its cover.[40]

Parker arranged Presley's return to performing live. He made a deal with Kirk Kerkorian, owner of the Las Vegas International Hotel, for Presley to play the newly built, 2,000-seat showroom for four weeks (two shows per night, with Mondays off) for $400,000.[41] For his appearance, he assembled a band later known as the TCB Band: James Burton (guitar), John Wilkinson (rhythm guitar), Jerry Scheff (bass-guitar), Ronnie Tutt (drums), Larry Muhoberac (piano) and Charlie Hodge (rhythm guitar, background vocals). The band was accompanied by the backing vocals of The Sweet inspirations and The Imperials.[42] His initial Las Vegas show attracted an audience of 101,500 — a new Vegas performance record.[41] By 1970, Presley began to tour the United States for the first time in 13 years.[43]

Media releases

Re-releases

NBC rebroadcast the special in the summer of 1969. The song "Blue Christmas" was replaced by the number "Tiger Man", at Parker's request. [44] In 1977, the program was aired in a special presented after his death by Ann-Margret called Memories of Elvis. It included a bordello scene, which was originally approved by the censors, but removed by the Singer Corporation to avoid controversy.[45]

In 1985, HBO broadcast the first sit-down session of the show under the title Elvis: One Night With You. Elvis Presley Enterprises' business manager Joe Rascoff sold the channel the broadcasting rights for $1,000,000. A home video version was later released.[46] The same year, the original broadcast of the special was released on home video. [47]

In 2004, Elvis: '68 Comeback Special Deluxe Edition DVD was released. The three disc set contained all the known available footage of the special, outtakes included. A single-disc edition was released in 2006 with the program expanded to 94 minutes, by adding material from the outtakes to the original broadcast.[48]

In 2018, 'Elvis ’68 Comeback Special: 50th Anniversary Celebration' saw the Television Special remastered and distributed to over 500 theaters across America.

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Soundtrack

The first single of the special released was "If I Can Dream" by RCA Victor (47–9670) in October 1968. It reached number twelve on the Billboard Singles chart, while it sold eight hundred thousand copies.[67] In November 1968, the live performance of "Tiger Man" appeared on the RCA Camden compilation album Elvis Sings Flaming Star (PRS-279), which was first released through Singer Sewing Machine stores and given wide release in April 1969 (CAS 2304).[68] In March 1969, RCA released "Memories" as a single (47–9730)

bootleg albums featuring non-issued material began circulating as early as 1978.[69] Over the following decades, additional performances from the TV Special were released in parts, particularly in RCA's A Legendary Performer compilation series,[70] as well as in the 1985 box set A Golden Celebration, although In the 1990s and 2000s, RCA issued more-complete soundtrack recordings. In 1998, it issued Memories, a 30th anniversary release that was an expansion of the original NBC-TV Special album. That same year RCA released Tiger Man which consisted of the complete sit-down performances. In 2006, RCA released Let Yourself Go: The Making of Elvis the Comeback Special, which consisted of outtakes and rehearsal recordings from the special.[71]

Various '68 Comeback recordings were used as the soundtrack to the Elvis pinball machine, released by Stern in 2004. The version of "A Little Less Conversation" originally recorded for (but not used in) the special was later remixed and became a hit single in 2002.[72] In the United States, the song peaked at number 50 on the Billboard Hot 100 pop singles chart, the first hit for Presley since 1981, and extending his list of charted singles into the 21st century. It also spent four consecutive weeks at number one on the UK Singles Chart.[73]

In popular culture

The sit-down sections of the special were a forerunner of MTV Unplugged, showing for the first time an artist in a casual setting.[25] In The Simpsons' 1993 episode "Krusty Gets Kancelled", the set of Krusty's television special mimicked Presley's show.[74] Falco's videoclip for his 1986 single "Emotional" features the Austrian singer standing in front of a huge logo formed by red lightbulbs, similar to the one used in the opening sequence of Presley's show, spelling out FALCO instead of ELVIS. The same logo is also used on the cover of his same-titled album. In the videoclip of the 2001 single "Inner Smile", Texas lead singer Sharleen Spiteri dressed as Presley in his Comeback Special looks.[75] Robbie Williams, in his 2002 DVD The Robbie Williams Show, borrowed from Presley's special the same opening song ("Trouble") with the same arrangement and a very similar staging, as well as the giant red logo (spelling out RW) and almost-identical sets for the concert performances. In 2004 Morrissey toured with a stage backdrop that spelled out MORRISSEY in large red marquee Comeback Special-style lights. [76] Also, Danzig loosely based his 2013 "Legacy" TV Special on the program. [77]

Footnotes

- ↑ Gordon, Robert 2005, pp. 110, 114.

- ↑ Ponce de Leon 2007, p. 133.

- ↑ Doll, Susan 2009, p. 113.

- ↑ Doll, Susan 2009, p. 141.

- ↑ Neibaur, James 2014, p. 230.

- ↑ Doll, Susan 2009, p. 137.

- ↑ Marsh 2004, p. 650.

- ↑ Doll, Susan 2009, p. 142.

- ↑ Guralnick, Peter 1999, p. 283.

- ↑ Adelman, Kim 2002, p. 143.

- ↑ Guralnick, Peter 1999, p. 288.

- ↑ Guralnick, Peter 1999, p. 293.

- ↑ Guralnick, Peter 1999, pp. 294-295.

- 1 2 Nash, Alanna 2008, p. 236, 238.

- ↑ Guralnick, Peter 1999, pp. 297.

- ↑ Guralnick, Peter 1999, pp. 299.

- ↑ Guralnick, Peter 1999, pp. 300.

- ↑ Nash, Alanna 2008, p. 236.

- ↑ Guralnick, Peter 1999, pp. 306.

- 1 2 Gaar, Gillian 2010, p. 79.

- ↑ EPE 2004, p. 8.

- ↑ EPE 2004, p. 7.

- ↑ Doll, Susan 2016.

- ↑ Weingarten, Mark 2000, p. 153.

- 1 2 3 Jeansonne, Glenn; Luhrssen, David; Sokolovic, Dan 2011, p. 181.

- ↑ NBC 1968.

- ↑ Eres, George 1968.

- ↑ Grow, Kory 2017.

- ↑ Kennedy, Paul 2011, p. 160.

- ↑ RIIA 2018.

- ↑ Shelton, Robert 1968.

- ↑ Penton, Edgard 1968.

- ↑ Burch, Mary 1968.

- ↑ Lowry, Cynthia 1968.

- ↑ Gardiner, Sandy 1968.

- ↑ Hopkins 2007, p. 215.

- ↑ Marsh 2004, p. 649.

- ↑ Klein, George; Crisafulli, Chuck 2011, p. 193.

- ↑ Collins, Ace 2005, p. 215.

- ↑ Otterburn-Hall, William 1969.

- 1 2 Jeansonne, Glenn; Luhrssen, David; Sokolovic, Dan 2011, p. 183.

- ↑ Eder, Mike 2013, p. 173.

- ↑ Wolff, Kurt 2000, p. 283.

- ↑ Rowan, Terry 2016, p. 56.

- ↑ Gaar, Gillian 2010, p. 310.

- ↑ Gaar, Gillian 2010, p. 311.

- ↑ Bowker 1999, p. 305.

- ↑ Gaar, Gillian 2010, p. 312.

- ↑ "The ARIA Report (Issue 755)" (PDF). Australian Recording Industry Association. Pandora Archive. p. 22. Retrieved August 10, 2011.

- ↑ "Austria Top 40 – Musik-DVD Top 10". Austrian Charts (in German). Hung Medien. Archived from the original (ASP) on November 6, 2012. Retrieved August 10, 2011.

- ↑ "Ultratop 10 Muziek-DVD" (ASP). Ultratop (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Archived from the original on November 2, 2012. Retrieved August 10, 2011.

- ↑ "Suomen virallinen lista – Musiikki DVD:t 30/2004" [Finland's Official List – Music DVDs 30/2004]. Musiikkituottajat – IFPI Finland (in Finnish). Archived from the original on August 20, 2011. Retrieved August 10, 2011.

- ↑ "Chartverfolgung / PRESLEY, ELVIS / Longplay". Music Line (in German). Media Control Charts. Archived from the original on October 17, 2012. Retrieved August 10, 2011.

- ↑ "Artist Ranking DVD". Oricon Style (in Japanese). Archived from the original on October 24, 2012. Retrieved August 10, 2011.

- ↑ "GfK Dutch DVD Music Top 30". Dutch Charts (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Archived from the original (ASP) on October 24, 2012. Retrieved August 10, 2011.

- ↑ "Top 10 Music DVDs". Recording Industry Association of New Zealand. Archived from the original (ASP) on June 11, 2012. Retrieved August 10, 2011.

- ↑ "Topp 10 DVD Audio: 2004 – Uke 31". VG-lista (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on June 3, 2012. Retrieved August 10, 2011.

- ↑ "Sverigetopplistan". Sverigetopplistan (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 2015-12-26. Search for Elvis Presley and click Sök.

- ↑ "Ultratop 10 Musicaux" (ASP). Ultratop (in French). Hung Medien. Archived from the original on November 2, 2012. Retrieved August 10, 2011.

- ↑ "ARIA Charts – Accreditations – 2011 DVDs". Australian Recording Industry Association.

- ↑ "Austrian video certifications – Elvis Presley – 68 Comeback Special" (in German). IFPI Austria. Enter Elvis Presley in the field Interpret. Enter 68 Comeback Special in the field Titel. Select DVD in the field Format. Click Suchen.

- ↑ "Canadian video certifications – Elvis Presley – Elvis: '68 Comeback Special". Music Canada.

- ↑ "French video certifications – Elvis Presley – '68 Comeback Special" (in French). Syndicat National de l'Édition Phonographique.

- ↑ "Latest Gold / Platinum Albums". Radioscope. 17 July 2011. Archived from the original on 2011-07-24.

- ↑ "American video certifications – Presley, Elvis – Elvis '68 Comeback – Special Edition". Recording Industry Association of America. If necessary, click Advanced, then click Format, then select Video Longform, then click SEARCH.

- ↑ "American video certifications – Presley, Elvis – Elvis: '68 Comeback Special Deluxe Edition". Recording Industry Association of America. If necessary, click Advanced, then click Format, then select Video Longform, then click SEARCH.

- ↑ Williamson, Joel 2014, p. 221.

- ↑ Moscheo, Joe 2007, p. 126.

- ↑ Osborne, Jerry 1983, p. 50.

- ↑ Osborne, Jerry 1983, p. 106.

- ↑ Gaar, Gillian 2010, p. 309.

- ↑ Gaar, Gillian 2010, p. 314.

- ↑ BBC 2002.

- ↑ Rabin, Nathan 2012.

- ↑ Eismann, Sonja 2008, p. 192.

- ↑ Paul, George; Swift, Kelly; Orange County Register, November 2 2004.

- ↑ Kajzer, Jackie 2013.

References

- Adelman, Kim (2002). The Girls' Guide to Elvis: The Clothes, The Hair, The Women, and More!. Crown/Archetype. ISBN 978-0-767-91189-4.

- BBC (2002). "Elvis and Oasis enjoy chart success". BBC News. BBC World Service. Retrieved August 21, 2017.

- Bowker (1999). Bowker's Complete Video Directory. R.R Bowker Publishing.

- Burch, Mary (1968). "Elvis Recalls Memories". The Daily Tar Heel. 76 (66). DTH Media Corp. Retrieved January 2, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- Collins, Ace (2005). Untold Gold: The Stories Behind Elvis's #1 Hits. Souvenir Press Ltd. ISBN 978-0-285-63738-2.

- Doll, Susan (2009). Elvis for Dummies. For Dummies. ISBN 978-0-470-47202-6.

- Doll, Susan (2016). Understanding Elvis: Southern Roots vs. Star Image. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-3177-3297-6.

- Eder, Mike (2013). Elvis Music FAQ: All That's Left to Know About the King's Recorded Works. Hal Leonard Corporation. ISBN 978-1-61713-580-4.

- Eismann, Sonja (2008). Hot Topic. Ventil-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-931-55575-7.

- EPE (2004). Elvis Presley's '68 Comeback Special [Deluxe Edition] (booklet). Elvis Presley. BMG.

- Eres, George (1968). "Presley Show Tops Rating". The Independent. 21 (252). Press-Telegram. Retrieved January 2, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- Gaar, Gillian (2010). Return of The King: Elvis Presley's Great Comeback. Jawbone Press. ISBN 978-1-906002-28-2.

- Gardiner, Sandy (1968). "Elvis Bridges Gap". Ottawa Journal. 83 (301). F.P. Publications. Retrieved January 2, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- Gordon, Robert (2005). The King on the Road. Bounty Books. ISBN 0-7537-1088-9.

- Grow, Kory (2017). "Inside Elvis Presley's Legendary 1968 Comeback Special". Rolling Stone. Wenner Media LLC. Retrieved January 3, 2018.

- Jeansonne, Glenn; Luhrssen, David; Sokolovic, Dan (2011). Elvis Presley, Reluctant Rebel: His Life and Our Times. ABC-Clio. ISBN 978-0-313-35904-0.

- Guralnick, Peter (1999). Careless Love: The Unmaking of Elvis Presley. Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 978-0-316-33222-4.

- Hopkins, Jerry. Elvis—The Biography. Plexus; 2007. ISBN 0-85965-391-9.

- Kajzer, Jackie (2013). "Glenn Danzig Talks 25th Anniversary of Debut Danzig Album, Upcoming Covers Disc + More". Loudwire. Townsquare Media, Inc. Retrieved January 3, 2018.

- Kennedy, Paul (2011). Warman's Elvis Field Guide: Values & Identification. Krause Publications. ISBN 978-1-440-22607-6.

- Klein, George; Crisafulli, Chuck (2011). Elvis: My Best Man. Random House. ISBN 978-1-4481-1262-3.

- Lowry, Cynthia (1968). "Special Programs Start Coming and Will Continue". Associated Press. 78 (221). The Evening Times (Sayre, Pennsylvania). Retrieved January 2, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- Marsh, Dave. "Elvis Presley". In: Marsh, Dave; Swenson, John, editors. The Rolling Stone Record Guide. 2nd ed. Virgin; 2004. ISBN 0-907080-00-6.

- Moscheo, Joe (2007). The Gospel Side of Elvis. Hachette UK. ISBN 978-1-599-95025-9.

- Nash, Alanna (2008). The Colonel: The Extraordinary Story of Colonel Tom Parker and Elvis Presley. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4391-3695-9.

- NBC (1968). "SINGER presents... Elvis". The Daily Tar Heel. 151 (133). DTH Media Corp. Retrieved January 2, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- Neibaur, James (2014). The Elvis Movies. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-4422-3074-3.

- Osborne, Jerry (1983). Presleyana: Elvis Presley record price guide. O'Sullivan Woodside. ISBN 978-0-890-19083-8.

- Otterburn-Hall, William (1969). "Elvis Presley On Set: You Won't ask Elvis Anything Too Deep?". Rolling Stone. Wenner Media, LLC. Retrieved January 31, 2018.

- Penton, Edgard (1968). "Elvis Tries New Stuff on an Old Audience". El Paso Herald-Post. 88 (287). E. W. Scripps Company. Retrieved January 2, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- Ponce de Leon, Charles L. (2007). Fortunate Son: The Life of Elvis Presley. Macmillan. ISBN 0-8090-1641-9.

- Rabin, Nathan (2012). "The Simpsons (Classic): "Krusty Gets Kancelled"". The A.V club. Onion, Inc. Retrieved January 3, 2018.

- RIIA (2018). "Gold & Platinum - RIIA". RIIA.com. Recording Industry Association of America. Retrieved January 3, 2018.

- Rowan, Terry (2016). Character-Based Film Series: Part Three. Lulu.com. ISBN 978-1-365-02128-2.

- Shelton, Robert (1968). "Rock Star's Explosive Blues Have Vintage Quality". The New York Times. The New York Times Company. Retrieved January 6, 2018.

- Williamson, Joel (2014). Elvis Presley: A Southern Life. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-199-86318-1.

- Weingarten, Mark (2000). Station To Station: The Secret History of Rock & Roll on Television. Gallery Books. ISBN 978-0-6710-3444-3.

- Wolff, Kurt (2000). Country Music: The Rough Guide. Rough Guides. ISBN 978-1-85828-534-4.