Elamo-Dravidian languages

| Elamo-Dravidian | |

|---|---|

| (obsolete) | |

| Geographic distribution | South Asia, West Asia |

| Linguistic classification | Proposed language family |

| Subdivisions | |

| Glottolog | None |

| Part of a series on |

| Dravidian culture and history |

|---|

|

|

History

|

|

Regions

|

|

People |

| Portal:Dravidian civilizations |

The Elamo-Dravidian language family is a hypothesised language family that links the Dravidian languages of India to the extinct Elamite language of ancient Elam (present-day southwestern Iran). Linguist David McAlpin has been a chief proponent of the Elamo-Dravidian hypothesis.[1] According to McAlpin, the long-extinct Harappan language (the language or languages of the Indus Valley Civilization) might also have been part of this family. The hypothesis has gained attention in academic circles, but has been subject to serious criticism by linguists, and remains only one of several scenarios for the origins of the Dravidian languages.[note 1] Elamite is accepted by scholars to be a language isolate, unrelated to any other known language.[3]

Linguistic arguments

According to David McAlpin, the Dravidian languages were brought to India by immigration into India from Elam, located in present-day southwestern Iran.[4][5] McAlpin (1975) in his study identified some similarities between Elamite and Dravidian. He proposed that 20% of Dravidian and Elamite vocabulary are cognates while 12% are probable cognates. He further claimed that Elamite and Dravidian possess similar second-person pronouns and parallel case endings. For example, the term for mother in the Elamite language and in different Dravidian languages like Tamil is amma.[6] They have identical derivatives, abstract nouns, and the same verb stem+tense marker+personal ending structure. Both have two positive tenses, a "past" and a "non-past".[7]

Georgiy Starostin criticized McAlpin's proposed morphological correspondences between Elamite and Dravidian as no closer than correspondences with other nearby language families,[8] while Bhadriraju Krishnamurti regarded them to be ad hoc, and found them to be lacking phonological motivation.[9] Similar criticisms are stated by Kamil Zvelebil and others.[9] Furthermore, Elamite is generally accepted by scholars to be a language isolate, unrelated to any other known language.[10][11][12]

Renfrew and Cavalli-Sforza have also argued that Proto-Dravidian was brought to India by farmers from the Iranian part of the Fertile Crescent,[13][14][15][note 2] but more recently Heggarty and Renfrew noted that "McAlpin's analysis of the language data, and thus his claims, remain far from orthodoxy", adding that Fuller finds no relation of Dravidian languages with other languages, and thus assumes it to be native to India.[2] Renfrew and Bahn conclude that several scenarios are compatible with the data, and that "the linguistic jury is still very much out."[2]

Proposed cultural links

Apart from the linguistic similarities, the Elamo-Dravidian hypothesis rests on the claim that agriculture spread from the Near East to the Indus Valley region via Elam. This would suggest that agriculturalists brought a new language as well as farming from Elam. Supporting ethno-botanical data include the Near Eastern origin and name of wheat (D. Fuller). Later evidence of extensive trade between Elam and the Indus Valley Civilization suggests ongoing links between the two regions.

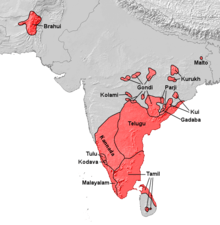

The distribution of living Dravidian languages, concentrated mostly in southern India but with isolated pockets in southern Afghanistan and Pakistan (Brahui) and in Central and East India (Kurukh, Malto), suggests to some a wider past distribution of the Dravidian languages. However, there are varied opinions about the origin of northern Dravidian languages like Brahui, Kurukh and Malto.[16] The Kurukh have traditionally claimed to be from the Deccan Peninsula,[17] more specifically Karnataka. The same tradition has existed of the Brahui.[18][19] They call themselves immigrants.[20] Many scholars hold this same view of the Brahui[21] such as L. H. Horace Perera and M. Ratnasabapathy.[22] Moreover, it has now been demonstrated that the Brahui only migrated to Balochistan from central India after 1000 CE. The absence of any older Iranian loanwords in Brahui supports the connection. The main Iranian contributor to Brahui vocabulary, Balochi, is a Western Iranian language like Kurdish.[23]

Archaeogenetics

According to genetic studies, the Brahui population has high prevalence (55%) of western Eurasian mtDNAs and the lowest frequency in the region (21%) of haplogroup M*, which is common (∼60%) among the Dravidian-speaking Indians. So the possibility of the Dravidian presence in Baluchistan originating from recent entry of Dravidians of India should be excluded. It also shows their maternal gene pool is similar to Indo-Iranian speakers. The present Brahui population may have originated from ancient Indian Dravidian-speakers who may have relocated to Baluchistan and admixed with locals; however, no historical record supports this. So it is suggested that they are the last northern survivors of a larger Dravidian-speaking region before Indo-Iranian arrived. This would, if true, reinforce the proto-Elamo-Dravidian hypothesis.[24]

Notes

- ↑ Renfrew and Bahn conclude that several scenarios are compatible with the data, and that "the linguistic jury is still very much out."[2]

- ↑ Derenko: "The spread of these new technologies has been associated with the dispersal of Dravidian and Indo-European languages in southern Asia. It is hypothesized that the proto-Elamo-Dravidian language, most likely originated in the Elam province in southwestern Iran, spread eastwards with the movement of farmers to the Indus Valley and the Indian sub-continent."[15]

Derenko refers to:

* Renfrew (1987), Archaeology and Language: The Puzzle of Indo-European Origins

* Renfrew (1996), Language families and the spread of farming. In: Harris DR, editor, The origins and spread of Agriculture and Pastoralism in Eurasia, pp. 70–92

* Cavalli-Sforza, Menozzi, Piazza (1994), The History and Geography of Human Genes.

References

- ↑ Southworth, Franklin. "Rice in Dravidian". Springer. Retrieved 22 March 2014.

- 1 2 3 Heggarty, Paul; Renfrew, Collin (2014), "South and Island Southeast Asia; Languages", in Renfrew, Colin; Bahn, Paul, The Cambridge World Prehistory, Cambridge University Press

- ↑ Archaeologies of Text: Archaeology, Technology, and Ethics. Oxbow Books. p. 34.

- ↑ Dhavendra Kumar (2004), Genetic Disorders of the Indian Subcontinent, Springer, ISBN 1-4020-1215-2, retrieved 2008-11-25,

... The analysis of two Y chromosome variants, Hgr9 and Hgr3 provides interesting data (Quintan-Murci et al., 2001). Microsatellite variation of Hgr9 among Iranians, Pakistanis and Indians indicate an expansion of populations to around 9000 YBP in Iran and then to 6,000 YBP in India. This migration originated in what was historically termed Elam in south-west Iran to the Indus valley, and may have been associated with the spread of Dravidian languages from south-west Iran (Quintan-Murci et al., 2001). ...

- ↑ David McAlpin, "Toward Proto-Elamo-Dravidian", Language vol. 50 no. 1 (1974); David McAlpin: "Elamite and Dravidian, Further Evidence of Relationships", Current Anthropology vol. 16 no. 1 (1975); David McAlpin: "Linguistic prehistory: the Dravidian situation", in Madhav M. Deshpande and Peter Edwin Hook: Aryan and Non-Aryan in India, Center for South and Southeast Asian Studies, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor (1979); David McAlpin, "Proto-Elamo-Dravidian: The Evidence and its Implications", Transactions of the American Philosophical Society vol. 71 pt. 3, (1981)

- ↑ The Cambridge History of Iran 2 by I. Gershevitch p.13

- ↑ David McAlpin, "Toward Proto-Elamo-Dravidian", Language vol. 50 no. 1 (1974); David McAlpin: "Elamite and Dravidian, Further Evidence of Relationships", Current Anthropology vol. 16 no. 1 (1975); David McAlpin: "Linguistic prehistory: the Dravidian situation", in Madhav M. Deshpande and Peter Edwin Hook: Aryan and Non-Aryan in India, Center for South and Southeast Asian Studies, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor (1979); David McAlpin, "Proto-Elamo-Dravidian: The Evidence and its Implications", Transactions of the American Philosophical Society vol. 71 pt. 3, (1981)

- ↑ Starostin, George (2002). "On the genetic affiliation of the Elamite language" (PDF). Mother Tongue. 7: 147–170.

- 1 2 Krishnamurti, Bhadriraju. The Dravidian Languages. Cambridge University. p. 44.

- ↑ Roger Blench, Matthew Spriggs (eds.)(2003), "Archaeology and Language I: Theoretical and Methodological Orientations", Routledge, p.125

- ↑ Roger D. Woodard (ed.)(2008), "The Ancient Languages of Mesopotamia, Egypt and Aksum", Cambridge University Press, p.3

- ↑ Amalia E. Gnanadesikan (2011), "The Writing Revolution: Cuneiform to the Internet", John Wiley & Sons

- ↑ Cavalli-Sforza (1994), p. 221-222.

- ↑ Namita Mukherjee; Almut Nebel; Ariella Oppenheim; Partha P. Majumder (December 2001), "High-resolution analysis of Y-chromosomal polymorphisms reveals signatures of population movements from central Asia and West Asia into India" (PDF), Journal of Genetics, Springer India, 80 (3): 125–35, doi:10.1007/BF02717908, PMID 11988631, retrieved 2008-11-25,

... More recently, about 15,000–10,000 years before present (ybp), when agriculture developed in the Fertile Crescent region that extends from Israel through northern Syria to western Iran, there was another eastward wave of human migration (Cavalli-Sforza et al., 1994; Renfrew 1987), a part of which also appears to have entered India. This wave has been postulated to have brought the Dravidian languages into India (Renfrew 1987). Subsequently, the Indo-European (Aryan) language family was introduced into India about 4,000 ybp ...

- 1 2 Derenko (2013).

- ↑ P. 83 The Quest for the Origins of Vedic Culture: The Indo-Aryan Migration Debate by Edwin Bryant

- ↑ P. 18 The Orāons of Chōtā Nāgpur: their history, economic life, and social organization by Sarat Chandra Roy, Rai Bahadur; Alfred C Haddon

- ↑ P. 12 Origin and Spread of the Tamils By V. R. Ramachandra Dikshitar

- ↑ P. 32 Ideology and status of Sanskrit : contributions to the history of the Sanskrit language by Jan E M Houben

- ↑ P. 45 The Brahui language, an old Dravidian language spoken in parts of Baluchistan and Sind by Sir Denys Bray

- ↑ Ancient India; Culture and Thought By M. L. Bhagi

- ↑ P. 23 Ceylon & Indian History from Early Times to 1505 A. D. By L. H. Horace Perera, M. Ratnasabapathy

- ↑ J. H. Elfenbein, A periplous of the ‘Brahui problem’, Studia Iranica vol. 16 (1987), pp. 215–233.

- ↑ Quintana-Murci, Lluís; Chaix, Raphaëlle; Wells, R. Spencer; Behar, Doron M.; Sayar, Hamid; Scozzari, Rosaria; Rengo, Chiara; Al-Zahery, Nadia; Semino, Ornella (2004). "Where West Meets East: The Complex mtDNA Landscape of the Southwest and Central Asian Corridor". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 74 (5): 827–845. doi:10.1086/383236. PMC 1181978. PMID 15077202.

Further reading

- Krishnamurti, Bhadriraju (2003). The Dravidian Languages. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-77111-5.

- McAlpin, David W. (2003). "Velars, Uvulars, and the North Dravidian Hypothesis". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 123 (3): 521–546. JSTOR 3217749.

- McAlpin, David W. (2015). "Brahui and the Zagrosian Hypothesis". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 135 (5): 551–586. doi:10.7817/jameroriesoci.135.3.551.