Honours of Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer-Churchill, KG, OM, CH, TD, PC, DL, FRS, RA received numerous honours and awards throughout his career as a British Army officer, statesman and author.

Perhaps the highest of these was the state funeral held at St Paul's Cathedral, after his body had lain in state for three days in Westminster Hall,[1] an honour rarely granted to anyone other than a British monarch or consort. The funeral also saw one of the largest assemblages of statesmen in the world.[2]

Throughout his life, Churchill also accumulated other honours and awards. He was awarded 37 other orders and medals between 1885 and 1964. Of the orders, decorations and medals Churchill received, 20 were awarded by the United Kingdom, three by France, two each by Belgium, Denmark, Luxembourg and Spain, and one each by the Czech Republic, Egypt, Estonia, Libya, Nepal, the Netherlands, Norway, and the United States. Ten were awarded for active service as an Army officer in Cuba, India, Egypt, South Africa, the United Kingdom, France, and Belgium. The greater number of awards were given in recognition of his service as a minister of the British government.[3]

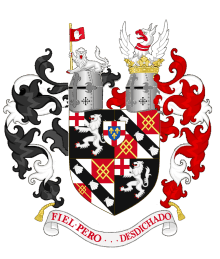

Coat of arms

Churchill was not a peer, never held a title of nobility, and remained a commoner all his life. As the grandson of 7th Duke of Marlborough, he bore the quartered coat of arms of the Spencer and Churchill families. Paul Courtenay observes that "It would be normal in these circumstances for the paternal arms (Spencer) to take precedence over the maternal (Churchill), but because the Marlborough dukedom was senior to the Sunderland earldom, the procedure was reversed in this case." In 1817 an augmentation of honour was granted commemorating the victory of Blenheim by the 1st Duke.[4]

As Churchill's father, Lord Randolph Churchill, was the surviving second son of the 7th Duke of Marlborough, his arms should have been differenced, by strict heraldic rules, with a mark of cadency. Traditionally, this would have been a heraldic crescent. Those differenced arms would have been inherited by Winston Churchill. This never seems to have been used by Lord Randolph or Winston. As arms are used to differentiate two bearers, there doesn't seem to have been any confusion between Churchill's arms as a gentleman with many decorations and later Knight of the Garter, those of his brother as a plain gentleman, and his cousin, the Duke of Marlborough, which were adorned with the insignia of a duke. As a Knight of the Garter, Churchill was also entitled to supporters in his achievement. But, he never seems to have got around to applying for them.[5]

The resulting heraldic achievement is: quarterly 1st and 4th, Sable a lion rampant Argent on a canton of the second a cross Gules (Churchill); 2nd and 3rd, quarterly Argent and Gules, in the second and third quarters a fret Or, over all on a bend Sable three escallops of the first (Spencer); in chief, on an escutcheon Argent a cross Gules surmounted by an inescutcheon Azure charged with three fleurs-de-lys Or.[4]

When he became a Knight of the Garter in 1953, his arms were encircled by the garter of the order, and at the same time the helms was made open, which is the mark of a knight. His motto was that of the Dukes of Marlborough, Fiel pero desdichado (Spanish for "Faithful but unfortunate").[6]

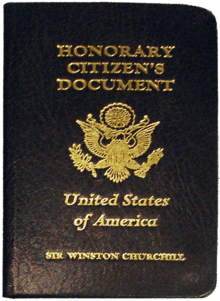

Honorary citizen

On 9 April 1963, United States President John F. Kennedy, acting under authorization granted by an Act of Congress, proclaimed Churchill the first honorary citizen of the United States. Churchill was physically incapable of attending the White House ceremony, so his son and grandson accepted the award for him.[7][8]

Proposed dukedom

In 1955, after retiring as Prime Minister, Churchill was offered elevation to the peerage in the rank of duke. By custom, Prime Ministers retiring from the Commons were usually offered earldoms, so the dukedom was a sign of special honour. One title that was considered was Duke of London, a city whose name had never been used in a peerage title. Churchill had represented divisions of three different counties in Parliament, and his home, Chartwell, was in a fourth, so the city in which he had spent most of his time during fifty years in politics was seen as a suitable choice.[9] Since 1900, only members of the British royal family have been made dukes, so the offer was exceptional.[10]

Churchill considered accepting the offer of a dukedom but eventually declined it; the lifestyle of a duke would have been expensive, and accepting any peerage might have cut short a renewed career in the Commons for his son Randolph and in due course might also prevent one for his grandson Winston.[9] (At the time there was no procedure for disclaiming a title; the procedure was first established by the Peerage Act 1963. Upon inheriting a peerage, either Randolph or Winston would immediately be unseated from the House of Commons.)[11] In the event, Randolph never sat in Parliament after losing his first and only seat there in 1945 and indeed was to die only three years after his father, so the dukedom would have had no effect on his career. Randolph's oldest son Winston did serve in the Commons from 1970 until 1997, but by that time provision existed for disclaiming a hereditary peerage.

Other honours

In 1913, Churchill was appointed an Elder Brother of Trinity House as result of his appointment as First Lord of the Admiralty.[12]

On 4 April 1939, Churchill was made an Honorary Air Commodore of No. 615 (County of Surrey) Squadron ("Churchill's Own") in the Auxiliary Air Force.[13] In March 1943, the Air Council awarded Churchill honorary wings.[10] He retained the appointment until 11 March 1957 when 615 Squadron was disbanded. He did however continue to hold the rank of Honorary Air Commodore.[14] He frequently wore his uniform as an Air Commodore during World War II.

He was the Colonel in Chief of the 4th Queen's Own Hussars (his old regiment) and after its amalgamation, the first Colonel in Chief of the Queen's Royal Irish Hussars which he held until his death in 1965. He was also Colonel in Chief of the Queen's Own Oxfordshire Hussars.

From 1941 to his death, he was the Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports, a ceremonial office. In 1941 Canadian Governor General Alexander Cambridge, Earl of Athlone, swore him into the King's Privy Council for Canada. Although this allowed him to use the honorific title The Honourable and the post-nominal letters PC, both of these were trumped by his membership in the Imperial Privy Council which allowed him the use of The Right Honourable.[10] He was also appointed Grand Seigneur of the Hudson's Bay Company in December 1955.

In 1945, he was mentioned by Halvdan Koht among seven candidates that were qualified for the Nobel Peace Prize. However, he did not explicitly nominate any of them. Actually he nominated Cordell Hull.[15]

Churchill held the office of Deputy Lieutenant (DL) of Kent in 1949.[16]

In 1953, he was awarded two major honours: he was invested as a Knight of the Garter (becoming Sir Winston Churchill, KG) and he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature "for his mastery of historical and biographical description as well as for brilliant oratory in defending exalted human values".[17]

He was Chancellor of the University of Bristol as well as in 1959, Father of the House, the MP with the longest continuous service.[18]

In 1956, Churchill received the Karlspreis (known in English as the Charlemagne Award), an award by the German city of Aachen to those who most contribute to the European idea, and European peace.[19]

In 1961 the Chartered Institute of Building[20] named Churchill as an Honorary Fellow for his services and passion for the construction industry.

In 1964, Civitan International presented Churchill its first World Citizenship Award for service to the world community.[21]

Churchill was also appointed a Kentucky Colonel.[22][23]

When Churchill was 88 he was asked by the Duke of Edinburgh how he would like to be remembered. He replied with a scholarship like the Rhodes scholarship but for the wider masses. After his death, the Winston Churchill Memorial Trust was established in the United Kingdom and Australia. A Churchill Trust Memorial Day was held in Australia, raising A$4.3 million. Since that time the Churchill Trust in Australia has supported over 3,000 scholarship recipients in a diverse variety of fields, where merit, either on the basis of past experience, or potential, and the propensity to contribute to the community have been the only criteria.

Namesakes

_English_Channel.jpg)

The Winston Churchill Range in the Canadian Rockies was named in his honour.

One of four specially made sets of false teeth, designed to retain Churchill's distinctive style of speech, which Churchill wore throughout his life, is now kept in the Hunterian Museum at the Royal College of Surgeons of England.[24]

Two Royal Navy warships have been named HMS Churchill: the destroyer USS Herndon (I45) (1940–1944) and the submarine HMS Churchill (1970–1991).

On 10 March 2001, the Arleigh Burke-class destroyer USS Winston S. Churchill (DDG-81) was commissioned into the United States Navy. The launch and christening of the ship two years earlier was co-sponsored by Churchill's daughter, Lady Soames.[25]

In addition, the Danish DFDS line named a car ferry Winston Churchill and The Corporation of Trinity House named one of their lighthouse tenders similarly. A sail training ship was named Sir Winston Churchill.

In September 1947, the Southern Railway named a Battle of Britain class steam locomotive No. 21C151 after him. Churchill was offered the opportunity to perform the naming ceremony, but he declined. The locomotive was later used to pull his funeral train, and is now preserved in the National Railway Museum, York.

He appeared on the 1965 crown, the first commoner to be placed on a British coin.[26] He made another appearance on a crown issued in 2010 to honour the 70th anniversary of his Premiership.[27]

Pol Roger's prestige cuvée Champagne, Cuvée Sir Winston Churchill, is named after him. The first vintage, 1975, was launched in 1984 at Blenheim Palace. The name was accepted by his heirs as Churchill was a faithful customer of Pol Roger. Following Churchill's death in 1965, Pol Roger added a black border to the label on bottles shipped to the UK as a sign of mourning. This was not lifted until 1990.[28]

The Churchill tank, or Infantry Tank Mk IV; was a British Second World War tank named after Churchill, who was Prime Minister at the time of its design.[29]

The Julieta (7" × 47), a size of cigar, is also commonly known as a Churchill.

The Churchill Park[30] (Danish: Churchillparken) located in central Copenhagen, Denmark, is name after Churchill in commemoration of Churchill and the British help to Denmark in the liberation of Denmark during World War II.

Polls

Churchill has been included in numerous polls, mostly connected with greatness. Time named him its Man of the Year for 1940,[31] and "Man of the Half-Century" in 1949.[32] A BBC survey, of January 2000, saw Churchill voted the greatest British prime minister of the 20th century. In 2002, BBC TV viewers and web site users voted him the greatest Briton of all time in a ten-part series called Great Britons, a poll attracting almost two million votes.[33]

Buildings, highways, statues and geographic features

Many statues have been created in likeness and in honour of Churchill. Numerous buildings and squares have also been named in his honour. The most prominent example of a statue of Churchill is the official statue commissioned by the government and created by Ivor Roberts-Jones which now stands in Parliament Square. It was unveiled by Churchill's widow, Lady Churchill, on 1 November 1973, and was Grade II listed in 2008.[34][35] Another Roberts-Jones statue of Churchill displaying the V sign[36] is prominently placed in New Orleans (1977). In addition several other statues have also been made, including a bronze bust of Winston Churchill by Jacob Epstein (1947), several statues by David McFall at Woodford (1959), William McVey outside the British embassy in Washington, D.C. (1966), Franta Belsky at Fulton, Missouri (1969), at least three from Oscar Nemon: one on the front lawn of the Halifax Public Library branch on Spring Garden Road, Halifax, Nova Scotia (1980); one in the British House of Commons (1969); a bust of his head along with that of Franklin Roosevelt commemorating the Quebec Conference, 1943 next to Port St. Louis in Quebec City (1998); and one in Nathan Phillips Square outside of Toronto City Hall (1977), and Jean Cardot beside the Petit Palais in Paris (1998).[37] A statue of Churchill and Roosevelt, sculpted by Lawrence Holofcener is located in New Bond Street, London.

After Churchill was declared the greatest Briton of all time in the BBC poll and television series Great Britons (see above), a statue was erected in his honour and now stands at the BBC television studios. Churchill is also memorialised by many statues and a public square in New York, in recognition of his life, and also because his mother was from New York. His maternal family is also memorialised in streets, parks, and neighbourhoods throughout the city.

The national and Commonwealth memorial to Churchill is Churchill College, Cambridge, which was founded in 1958 and opened in 1960. It is also home to the Churchill Archives Centre, which holds the papers of Sir Winston Churchill and over 570 collections of personal papers and archives documenting the history of the Churchill era and after.[38]

Many schools have been named after him:

Ten schools in Canada are named in his honour: one each in Vancouver, Winnipeg, Thunder Bay, Hamilton, Kingston, St. Catharines, Lethbridge, Calgary, Toronto (Scarborough) and Ottawa. Churchill Auditorium at the Technion is named after him.

At least four American high schools carry his name; these are located in Potomac, Maryland; Livonia, Michigan; Eugene, Oregon and San Antonio, Texas.

In London, Churchill Place is one of the main squares in Canary Wharf. Winston Churchill Avenue is a major road in Portsmouth. Basingstoke and Salford both have roads called Churchill Way.

The city of Edmonton, Alberta, Canada has a stop on the Edmonton LRT system and a public square named in his honour. Churchill Square, is the main square in that city and was renovated in 2004 for the city's 100th anniversary of incorporation. There are several other squares named after him, including one in Brighton, England and one in Newfoundland. The south end of Churchill Avenue in Ottawa was the site of the Churchill Arms Motor Hotel, which many residents of Ottawa remember for its three-storey exterior painting of the silhouette of Winston Churchill.[39] Churchill Avenue was itself renamed from Main Street after the Second World War. In St. Albert, Alberta Sir Winston Churchill Ave runs east to west through the city. Winston Churchill Boulevard in Mississauga, Ontario, Canada is also named in his honour.

Churchill National Park in Australia which was established on 12 February 1941 as the Dandenong National Park, was renamed in 1944 in his honour. The town of Churchill, Victoria, Churchill Island and Churchill Island Marine National Park in Victoria, Australia were also named after him.

In Canada, Sir Winston Churchill Provincial Park, Churchill Park, St. John's and Churchill Lake in Saskatchewan were all named after him.

A large dock in the Port of Antwerp was named after him by Queen Elizabeth II at a ceremony in 1966.

Náměstí W. Churchilla (Winston Churchill Square) is located behind The Main Train Station in Prague, Czech Republic.

In Gibraltar the main road connecting the border with Spain and the airport to the city centre is called Winston Churchill Avenue.

Churchillparken in Copenhagen, Denmark; Churchill Park, Glendowie, New Zealand; Churchill Park (Lautoka), Fiji; and Energlyn and Churchill Park railway station in Wales are some other parks named in his honour.

In Norway streets in the cities of Trondheim and Tromsø are named in Winston Churchill's honour. Namely "Churchills vei"[40] in Jakobsli, Trondheim and "Winston Churchills vei" in Tromsø.

The Churchill occupying an entire block in New York City's Midtown Manhattan neighborhood is a residential building named after him, and features his portrait in the lobby and rooftop pool (rare for NYC residences).[41] Many smaller, less significant streets and public buildings, particularly in the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia and New Zealand have been named in honour of Churchill.

Orders, decorations and medals

British orders and medals

_ribbon.png)

_ribbon.png)

Foreign

Orders

_pasador.svg.png)

Decorations

_-_ribbon_bar.png)

Service medals

.png)

(Although some references report Churchill was awarded the French Legion of Honour, it is not listed among his honours at the Churchill Centre. However, it is significant that Churchill received the Médaille militaire, which is only awarded (for high leadership) to holders of the Legion's Grand Cross). The Listing of Foreign recipients of the Legion of Honour reports Churchill as "Sir Winston Churchill, Grand-croix de la Légion d'honneur (1958);" (The Grand-croix being awarded to Foreign Heads of state).

Academic

- Fellow of the Royal Society (1941–1965)

- Rector of the University of Aberdeen (1914–18)

- Rector of Edinburgh University (1929–32)

- Chancellor of the University of Bristol (1929–1965)[47]

- Honorary Academician Extraordinary of the Royal Academy of Arts (1948–1965).[48]

- Honorary Professorship at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1949.

- Member of the Royal Academy of Science, Letters and Fine Arts of Belgium.[49]

Honorary degrees

- Honorary doctorates from British universities including University of Aberdeen, University of Liverpool, University of London

- Queens University, Belfast in Belfast Northern Ireland LL.D in 1926.[50]

- Honorary doctorates from the Rochester in New York LL.D on 16 June 1941[51] and Harvard LL.D on 6 September 1943[50]

- Honorary Doctorate from McGill University in Montreal, Quebec (LL.D) on 16 September 1944[52]

- Honorary doctorate in philosophy from the University of Copenhagen

- Honorary doctorate (LL.D) from Leiden University in The Netherlands (10 May 1946)[53]

- Honorary doctorate (LL.D) from the University of Miami in Florida (26 February 1946)[54]

- Westminster College in Fulton, Missouri LL.D on 5 May 1946.[55]

- University of London D.Litt in 1948.[56][57]

Military ranks and titles

- Cornet, 4th Queen's Own Hussars (20 February 1895)[58]

- Lieutenant, 4th Queen's Own Hussars (20 May 1896)[58]

- Lieutenant, South African Light Horse (January 1900)[58]

- Captain, Queen's Own Oxfordshire Hussars, Imperial Yeomanry (4 January 1902)[58]

- Major, Henley Squadron, Queen's Own Oxfordshire Hussars (5 May 1905)[58]

- Major, 2nd Battalion, Grenadier Guards (November 1915)[58]

- Lieutenant-Colonel (temporary), 6th Battalion, Royal Scots Fusiliers (5 January 1916 – March 1916)[58]

- Major, Territorial Army (March 1916 – 1924)[58]

- Honorary Air Commodore of No. 615 Squadron RAF (1939–1957)[59]

- Colonel, 4th Queen's Own Hussars (22 October 1941 – 1958)[60]

- Colonel, Queen's Royal Irish Hussars (1958–1965)[61]

- Honorary Colonel, Queen's Own Oxfordshire Hussars[62]

- Honorary Colonel, Royal Artillery, Territorial Army (21 October 1939 – 1965)[63]

- Honorary Colonel, 6th Battalion, Royal Scots Fusiliers (24 January 1940)[64]

- Honorary Colonel, 4th/5th (Cinque Ports) Battalion, Royal Sussex Regiment (24 January 1940)[65]

- Major, Territorial Army, Retired (20 February 1942)[63]

- Honorary Colonel, 489th (Cinque Ports) Heavy Anti-Aircraft Regiment, RA, Territorial Army (1947–1955)

- Honorary Pilot Wings, United States Air Force[59]

- Colonel, Honorable Order of Kentucky Colonels[59]

Political and government offices

- Member of Parliament (1901–1922, 1924–1964)

- Under Secretary of State for the Colonies (1905–1908)

- Privy Counsellor (1907–1965)

- President of the Board of Trade (1908–1910)

- Home Secretary (1910–1911)

- First Lord of the Admiralty (1911–1915, 1939–1940)

- Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster (1915)

- Minister of Munitions (1917–1919)

- Secretary of State for War and Secretary of State for Air (1919–1922)

- Chancellor of the Exchequer (1924–1929)

- Prime Minister of the United Kingdom (1940–1945, 1951–1955)

- Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports (1941–1965)[66]

- King's Privy Council for Canada (29 December 1941)[67]

- Leader of the Opposition (1945–1951)

- Father of the House of Commons (1959–1964)

Other distinctions

- Nobel Prize in Literature (1953){{https://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/literature/laureates/1953/}}

- Albert Gold Medal, Royal Society of Arts (1945)

- Grotius Medal, Netherlands (1949)

- Grand Seigneur of the Hudson's Bay Company (1955)[68]

- Karlspreis (1956)[69]

- The Williamsburg Award (7 December 1955)[70]

- Franklin Medal, City of Philadelphia, US (1956)

- 1st World Citizenship Award from Civitan International (1964)

- Theodor Herzl Award, Zionist Organization of America (1964)

- Honorary Bencher, Gray's Inn (1942)

- Honorary Member, Lloyd's of London

- Honorary Life Member, Veteran's Fire Engine Company, Alexandria, Virginia (1960)

- Member of Amalgamated Union of Building Trade Workers

- President of the Victoria Cross and George Cross Association 1959–1965.[71]

Membership in lineage societies

- Royal Society of St George (Vice President)

- Society of the Cincinnati (1952)[72]

- Sons of the American Revolution (1963)

Freedom of the City

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

Churchill received a worldwide total of 42 Freedoms of cities and towns, in his lifetime a record for a lifelong British citizen.[119]

Sources

- ↑ Picknett, et al., p. 252.

- ↑ Gould, Peter (8 April 2005). "Europe | Holding history's largest funeral". BBC News. Retrieved 9 August 2009.

- ↑ "The Life of Churchill".

- 1 2 Paul Courtenay, The Armorial Bearings of Sir Winston Churchill The Armorial Bearings of Sir Winston Churchill Archived 18 July 2013 at the Wayback Machine. (accessed 20 July 2013).

- ↑ Paul Courtenay, The Armorial Bearings of Sir Winston Churchill [https://www.winstonchurchill.org/resources/reference/the-armorial-bearings-of-sir-winston-churchill/ The Armorial Bearings of Sir Winston Churchill Archived 18 July 2013 at the Wayback Machine. (accessed 02 February 2018).

- ↑ Robson, Thomas, The British Herald, or Cabinet of Armorial Bearings of the Nobility & Gentry of Great Britain & Ireland, Volume I, Turner & Marwood, Sunderland, 1830, p. 401 (CHU-CLA).

- ↑ Plumpton, John (Summer 1988). "A Son of America Though a Subject of Britain". Finest Hour (60).

- ↑ HelmerReenberg (29 May 2013). "April 9, 1963 - President John F. Kennedy declares Winston Churchill an honorary citizen of the USA" – via YouTube.

- 1 2 Ramsden, John (2002). Man of the Century: Winston Churchill and His Legend Since 1945. Columbia University Press. pp. 113, 597. ISBN 9780231131063.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 The Orders, Decorations and Medals of Sir Winston Churchill by Douglas Russell

- ↑ "Welcome to WinstonChurchill.org". Archived from the original on 7 February 2007.

- ↑ Fedden, Robin (15 May 2014). Churchill at Chartwell: Museums and Libraries Series. Elsevier. ISBN 9781483161365.

- ↑ "Questions Answered: Winston Churchill in uniform and Ralph or Rafe". The Times. 13 September 2008. Retrieved 14 June 2010.

- ↑ "No. 41083". The London Gazette (Supplement). 28 May 1957. p. 3227.

- ↑ "Record from The Nomination Database for the Nobel Prize in Peace, 1901–1956". Nobel Foundation. Archived from the original on 4 September 2013. Retrieved 14 May 2010.

- ↑ Lundy, Darryl. "Biography Rt. Hon. Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill". The Peerage. – website thePeerage.com

- ↑ "Literature 1953". Nobelprize.org. Retrieved 9 August 2009.

- ↑ "Winston Churchill hero file". AU: More or Less. Archived from the original on 16 October 2009. Retrieved 9 August 2009.

- ↑ "Internationaler Karlspreis zu Aachen – Detail". DE: Karlspreis. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 9 August 2009.

- ↑ CIOB

- ↑ Armbrester, Margaret E. (1992). The Civitan Story. Birmingham, AL: Ebsco Media. pp. 96–97.

- ↑ "Colonels web site". Kycolonels.org. Archived from the original on 25 June 2009. Retrieved 9 August 2009.

- ↑ "Kentucky: Secretary of State – Kentucky Colonels". Sos.ky.gov. 26 October 2006. Archived from the original on 9 July 2009. Retrieved 9 August 2009.

- ↑ "The Teeth That Saved The World? — The Royal College of Surgeons of England". 29 November 2005. Archived from the original on 22 April 2007.

- ↑ "Home – USS W.S. Churchill". Churchill.navy.mil. Retrieved 9 August 2009.

- ↑ "1965 Churchill Crown". 24carat.co.uk. Retrieved 9 August 2009.

- ↑ "Winston Churchill £5 Crown from the British Royal Mint". CoinUpdate.com. Retrieved 23 July 2010.

- ↑ Pol Roger UK: Sir Winston Churchill Archived 14 July 2007 at the Wayback Machine., accessed 12 July 2010

- ↑ Chris Shillito. "The Churchill Tank". Armourinfocus.co.uk. Retrieved 9 August 2009.

- ↑ "Churchillparken". 7 December 2017 – via Wikipedia.

- ↑ "GREAT BRITAIN: Man of the Year". Time. 6 January 1941. Retrieved 26 December 2010.

- ↑ "Winston Churchill, Man of the Year". Time. 2 January 1950. Retrieved 26 December 2010.

- ↑ BBC – Great Britons.

- ↑ Sherna Noah (1 January 2004). "Churchill statue 'had the look of Mussolini'". The Independent. Retrieved 18 August 2011.

- ↑ "Sir Winston Churchill". Greater London Authority. Archived from the original on 12 July 2011. Retrieved 18 August 2011.

- ↑ "Winston Churchill - New Orleans, LA - Statues of Historic Figures on Waymarking.com".

- ↑ "Churchill, Sir Winston Leonard Spencer (1874–1965), prime minister - Oxford Dictionary of National Biography".

- ↑ "Churchill College : Churchill Archives Centre". Chu.cam.ac.uk. 6 March 2009. Retrieved 9 August 2009.

- ↑ "Sale threatens future of Churchill Arms". Ottawa Citizen. 1 April 1986. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- ↑ Norway Rd (1 January 1970). "Churchill NOrway – Google Maps". Maps.google.com. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- ↑ http://streeteasy.com/building/the-churchill

- ↑ ČTK. "Seznam osobností vyznamenaných letos při příležitosti 28. října". ceskenoviny.cz. (in Czech)

- ↑ "White Lion goes to Winton and Winston". The Prague Post. Archived from the original on 17 January 2016. It was conferred on same occasion as the same award was given to Sir Nicholas Winton.

- ↑ "Luxembourg's WW2 Medals". Users.skynet.be. Archived from the original on 13 August 2013. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- ↑ "Khedive's Sudan Medal 1896–1908".

- ↑ Cuban Campaign Medal, 1895–98 Archived 19 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Bristol University - News - 2004: Chancellor".

- ↑ "Sir Winston Churchill - Artist - Royal Academy of Arts". www.royalacademy.org.uk.

- ↑ Index biographique des membres et associés de l'Académie royale de Belgique (1769–2005). p. 55

- 1 2 "Brothers in Arms: Winston Churchill Receives Honorary Degree - Harvard Library". library.harvard.edu.

- ↑ "Commencement history: Winston Churchill addresses Class of 1941 by radio". 11 May 2016.

- ↑ https://www.mcgill.ca/secretariat/files/secretariat/hon-alph_2.pdf%5Bpermanent+dead+link%5D

- ↑ "Leiden Classics: how Winston Churchill was awarded an Honorary Doctorate - News - News & Events".

- ↑ https://www6.miami.edu/commencement/history.html

- ↑ "National Churchill Museum - Blog". www.nationalchurchillmuseum.org.

- ↑ British Pathé (13 April 2014). "London Varsity Honours Churchill (1948)" – via YouTube.

- ↑ British Pathé (13 April 2014). "Churchill Degree (1948)" – via YouTube.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Olsen, John. "Churchill's Commissions and Military Attachments". Retrieved 12 March 2017.

- 1 2 3 Who Was Who, 1961–1970. p. 206.

- ↑ The Quarterly Army List, July 1942. Vol. 1., p. 317.

- ↑ "4th Queen's Own Hussars". regiments.org. Archived from the original on 3 March 2006. Retrieved 2 October 2016.

- ↑ "Queen's Own Oxfordshire Hussars". Regiments.org. Archived from the original on 19 December 2007. Retrieved 15 January 2017.

- 1 2 The Quarterly Army List, July 1942. Vol. 1., p. 474.

- ↑ The Quarterly Army List, July 1942. Vol. 1., p. 925.

- ↑ The Quarterly Army List, July 1942. Vol. 1., p. 1067.

- ↑ "No. 35326". The London Gazette. 28 October 1941. p. 6247.

- ↑ "Privy Council Office - Bureau du Conseil privé".

- 1 2 British Pathé (13 April 2014). "Presentation To Winston Churchill At Beaver Hall (1956)" – via YouTube.

- ↑ British Pathé (13 April 2014). "Aachen Honours Churchill (1956)" – via YouTube.

- ↑ Colonial Williamsburg (30 March 2011). "Presentation of the Williamsburg Award (Churchill Bell Award) to Sir Winston Churchill" – via YouTube.

- ↑ Association, Victoria Cross and George Cross. "The VC and GC Association". vcgca.org.

- ↑ "The Society of the Cincinnati". societyofthecincinnati.org. Retrieved 27 November 2016.

- ↑ Oldham Council. "Honorary Freemen of the Borough".

- ↑ British Pathé (13 April 2014). "Premier In Scotland Aka Churchill In Scotland (1942)" – via YouTube.

- ↑ British Pathé (13 April 2014). "Churchill A Freeman Aka Churchill Made A Freeman Of London (1943)" – via YouTube.

- ↑ http://www.aparchive.com/metadata/youtube/e0fca7aa7af54b9eb12cde016eabbb77

- ↑ "Autumn 1945 (Age 70) - The International Churchill Society". 20 March 2015.

- ↑ "When Blackpool Gave Freedom of the Borough to Winston Churchill - Blackpool Winter Gardens Trust". www.wintergardenstrust.org.uk. Archived from the original on 5 April 2017. Retrieved 5 April 2017.

- ↑ "When Sir Winston Churchill received special honour from Poole". Bournemouth Echo.

- ↑ British Movietone (21 July 2015). "CHURCHILL RECEIVES FREEDOM OF WESTMINSTER" – via YouTube.

- ↑ British Pathé. "Churchill: Freedom Of Manchester".

- ↑ British Pathé (13 April 2014). "Churchill Receives Freedom Of Manchester (1947)" – via YouTube.

- ↑ British Pathé (13 April 2014). "Winston Churchill Receives Freedom Of Ayr Aka Pathe Front Page (1947)" – via YouTube.

- ↑ Ramsden, John (2002). Man of the Century: Winston Churchill and His Legend Since 1945. Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231131063.

- ↑ "Freedom of the Borough - Corporation and Council - Topics - My Brighton and Hove". Retrieved 12 March 2017.

- ↑ British Pathé (13 April 2014). "Churchill Receives Freedom Of Brighton (1947)". Retrieved 12 March 2017 – via YouTube.

- ↑ "Mr Winston Churchill seen receiving the Freedom of Eastbourne, Sussex from Councillor Randolph E as a 22"x18" (58x48cm) Framed Print". Media Storehouse.

- ↑ Reno Gazette-Journal, 22 April 1948, p. 14

- ↑ "Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill".

- ↑ https://www.cardiff.gov.uk/ENG/Your-Council/Lord-Mayor/honorary-freedom/Documents/freedom%20roll%20list%20June%202014.pdf

- ↑ British Pathé (13 April 2014). "Churchill Gets Freedom Of Cardiff (1948)". Retrieved 12 March 2017 – via YouTube.

- ↑ "Full record for 'CHURCHILL RECEIVES THE FREEDOM OF PERTH' (0841) - Moving Image Archive catalogue".

- ↑ "Appointment of Honorary Persons". Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- ↑ British Pathé (13 April 2014). "Churchill Receives Freedom Of Kensington (1949)". Retrieved 12 March 2017 – via YouTube.

- ↑ British Pathé (13 April 2014). "Selected Originals - Churchill Receives Freedom Of Worcester (1950)" – via YouTube.

- ↑ "The Telegraph-Herald - Google News Archive Search".

- ↑ British Pathé (13 April 2014). "'pompey's' New Freeman (1950)" – via YouTube.

- ↑ "On this day from Monday, February 27 2017". Swindon Advertiser.

- ↑ "Picture Sheffield".

- ↑ "Retro: Sheffield honours Churchill with freedom of city".

- ↑ "Retro: Sheffield honours Churchill with freedom of city". www.thestar.co.uk.

- ↑ British Pathé (13 April 2014). "Selected Originals - Two Freedoms For Churchill (1951)" – via YouTube.

- ↑ "Eliot Crawshay-Williams - Program Signed 08/15/1951 - Autographs & Manuscripts - HistoryForSale Item 52843". HistoryForSale Autographs & Manuscripts.

- ↑ Talat Chaudhri. "Honorary Freemen".

- ↑ "Dover's Home Guard". 16 April 2016.

- ↑ "City Schedules Churchill Fete". The Windsor Daily Star. 17 January 1953. p. 13.

- ↑ "Churchill Visits Jamaica". Colonial Film. Retrieved 15 August 2013.

- ↑ "Churchill is awarded The Freedom of Portsmouth".

- ↑ "Freedom of the city & keys of the city".

- ↑ "Freedoms granted by Harrow".

- ↑ "Freedom of city was last granted in 1963". The Irish Times. 2 May 2000.

- ↑ "The Glasgow Herald - Google News Archive Search".

- ↑ "SIR WINSTON CHURCHILL RECEIVES FREEDOM OF THE CITY OF BELFAST & LONDONDERRY". Archived from the original on 9 January 2013.

- ↑ British Pathé (13 April 2014). "Selected Originals - Ulster Honours Churchill Aka Ulster Honours Sir Winston Aka Churchill 2 (1955)" – via YouTube.

- ↑ British Movietone (21 July 2015). "SIR WINSTON CHURCHILL - HONORARY CITIZEN" – via YouTube.

- ↑ https://winstonchurchill.org/resources/in-the-media/churchill-in-the-news/emery-and-wendy-reves-qla-pausaq-goes-on-sale/

- ↑ "Douglas Borough Council - Freedom of the Borough of Douglas". www.douglas.gov.im.

- ↑ Sandys, Celia (2014). Chasing Churchill: The Travels of Winston Churchill. Andrews UK Limited. ISBN 9781910065297.

- ↑ McWhirter, Ross and Norris (1972). The Guinness Book of Records. Guinness Superlatives Ltd. p. 184. ISBN 0900424060. At the time of publication the world record was the 57 conferred on Andrew Carnegie who was born in Scotland but emigrated in 1848, subsequently becoming a US citizen.