Dominic Bruce

| Dominic Bruce | |

|---|---|

Dominic Bruce | |

| Nickname(s) | The "Medium Sized Man" |

| Born |

7 June 1915[1] Hebburn, County Durham, England |

| Died |

12 February 2000 (aged 84) Richmond, Surrey, England |

| Allegiance | United Kingdom |

| Service/ | Royal Air Force |

| Years of service | 1935–1946 |

| Rank | Flight Lieutenant |

| Service number | 45272[2] |

| Unit |

No. 9 Squadron No. 214 Squadron |

| Battles/wars | World War II |

| Awards |

Officer of the Order of the British Empire Military Cross Air Force Medal Knight of the Order of St. Gregory the Great |

| Other work | College Principal |

Flight Lieutenant Dominic Bruce OBE MC AFM (7 June 1915 – 12 February 2000) was a British Royal Air Force officer, known as the "Medium Sized Man."[3][4] He has been described as "the most ingenious escaper" of World War II.[5] During the Second World War he made seventeen attempts at escaping from POW camps, including several attempts to escape from Colditz Castle, a castle that housed prisoners of war deemed incorrigible.

Famed for his time in Colditz, Bruce also escaped from Spangenberg Castle and the Warburg POW camp. In Spangenberg Castle he escaped with the Swiss Red Cross Commission escape, it is also argued he co-innovated the wooden horse escape technique whilst serving time inside Spangenberg. In Warburg he escaped dressed as a British orderly in a fake workers party. Inside Colditz Castle, Bruce authored the Tea Chest Escape and also faced a firing squad for an attempted escape via a sewer tunnel. Whilst held in solitude in Colditz, along with two other prisoners, Bruce became a key witness to the post war Musketoon, commando raid trial.

For his exploits in WWII he was awarded the Military Cross and is the only known person to have received both the Military Cross and the Air Force Medal.

In his later years he received the OBE for his services to education.

Early years

Bruce was born on 7 June 1915, in Hebburn,[1] County Durham, England. He was the second of the four children of William and Mary Bruce.[1] Mary (née McClurry) Bruce was awarded the British Empire Medal in 1956 for her services to the care of the sick and infirm and was known as the 'Angel of Hebburn'. His older brother was Brother Thomas (William) Bruce FSC, a member of the De La Salle religious congregation or Institute of the Brothers of the Christian Schools who died in Nazareth in 1974, and is buried in a wall tomb in the crypt of the University of Bethlehem. His two younger siblings were Anne Bruce-Kimber and John Bruce (who died in infancy). Dominic Bruce's escaping adventures started early in his life when he ran away from home by means of a train to London. Remarkably on arrival in London he was recognised by a police officer married to his father's sister Anne. He was quickly returned to Shakespeare Avenue in Hebburn. Bruce was educated at and matriculated from St Cuthbert's Grammar School, Newcastle, 1927-1935.[1] He was of an adventurous disposition and as an alternative to his formal education he spent some time as an unauthorised visitor to the Newcastle law courts[note 1] during school time.[7] Bruce doubtlessly would have made a formidable legal adversary in later life should his family had the means for him to pursue a legal career after matriculation.

Bruce married Mary Brigid Lagan on 25 June 1938 at Corpus Christi Catholic Church, Maiden Lane, London, WC2.

Early RAF career

On joining the Royal Air Force in 1935 he trained as an wireless operator.[8] Later he was posted to No. 9 Squadron and became a navigator. On 25 March 1937 he was involved in the crash of the Handley Page Harrow "K6940" which resulted from a badly judged descent which removed the roof of a train travelling on railway lines adjacent to the Handley Page works airfield at Radlett.[9][10]

Air Force Medal

On 6 October 1938, while with No. 214 Squadron, he survived the crash of Harrow "K6991" at Pontefract, Yorkshire.[11] While acting as a wireless operator for his aircraft he was knocked out by a lightning strike.[12] Once recovered he alerted his base to the fact that the crew were bailing out. Wishing to get out of an escape hatch he found his way blocked by other airmen who were hesitating about throwing themselves out of the aircraft into the howling darkness. He rushed to the other side of the hatch and jumped. His parachute harness caught on projecting clamps and pulled the trapdoor shut above him. Bruce was now suspended under the bomber and unable to escape further. Realising what had happened his fellow crew members were now galvanised into action raised the trapdoor and were shocked to have Bruce shoot back into the aircraft, though not too shocked to eject him again. Bruce was subsequently awarded the Air Force Medal (AFM) on 8 June 1939.[13][note 2] According to Pete Tunstall, Bruce was very proud of being the only man known to have bailed from an aircraft three times and to have landed only twice.[14] After the war he used to entertain his children with the seemingly insoluble riddle: "How is it that I baled out three times, but only landed twice?" Bruce called his AFM medal the 'Away From Mam' medal.[12]

WWII

At the outbreak of war, in 1939, Bruce had been trained as a navigator with RAF No.9 Squadron.[12] The mortality risk for RAF Bomber Command aircrew in World War II was significant. His role as a navigator would have involved keeping the aircraft on course at all times.[15] He would have had to have had a high level of concentration as missions could last up to seven hours.[15]

On 20 January 1941 Acting Flight Sergeant Bruce was granted a commission "for the duration of hostilities" as a probationary pilot officer, with seniority from 8 January.[2]

Camaraderie with messmates

Pranks

Bruce was a notorious prankster. In Pat Reid's book about Colditz he describes how a group of new Navy entrants to the castle were horrified when a uniformed German doctor (in fact, Howard Gee, one of the 'prominente' hostages) insisted that they were lice ridden and must strip naked for their private parts be treated by his medical orderly. This alarming figure in white overalls would approach each man with a lavatory brush dipped in a bucket of evil smelling blue liquid (consisting of lavatory disinfectant and theatrical paint) and dabbed each man's genitals. The new boys would later realise that the evilly grinning orderly was Bruce.[16]

In the IWM interview tapes held in the Imperial War Museum Sound Archive, Bruce tells the tale of a bombing mission over Berlin when he persuaded the pilot to descend to five hundred feet over the city. Bruce climbed down into the now empty bomb bay, hand cranked the doors open; sat on the bomb rack and threw a lit distress flare out of the plane. When asked later why, he answered "Because I've always wanted to see the Unter den Linden lit up at night."[17][18]

Bruce, like a lot of his comrades, participated in goon baiting. In his book 'Colditz: the German Story' (1961, translation by Howard Gee), Reinhold Eggers, the castle's Security Officer, describes how Bruce was fond of sowing confusion amongst the German guards during Appel, or roll call, using the 'rabbit run' prank. Bruce would stand in the ranks, wait until he had been counted, then duck quickly along the line, only to be counted again at the other end. This trick was also used for more serious purposes, to cover up for a missing escapee.[19]

John 'Bosun' Chrisp explained that after their sewer drain escape attempt, Bruce, billed the Kommandant and Staff Paymaster Heinze in the castle for £600 on behalf of Messrs Chrisp, Lorraine and Bruce, for their service of cleaning the drains that had not been cleaned for 300 years.[20]

Nicknames

In his IWM interview tapes he tells how he fooled the King's cousin Viscount Lascelles (later the Earl of Harewood, he was being kept in Colditz as a hostage by the SS) into believing that the average or medium size of home sapiens was 5 feet 3 inches (his own height). When Lascelles told his mess mates about this novel theory it did not take them long to discover who had fooled him. That resulted in his nickname, 'the Medium Sized Man'.[17][18] Bruce was also was known as 'Brucie' or 'Bruce.'[14]

During his failed escape under the wire at Colditz he discovered his German nickname, as the guard who fell over him in the dark (and in his fright shot at Bruce, just barely missing his eyebrow) answered the security patrol's question as to who it was by saying 'Der Kleine' ('the little one'). The sentry overcame his shock only to burst out laughing when Bruce shouted "I surrender" in an effort to prevent him shooting again. When he emerged from his six week sentence in solitary confinement he asked another prisoner, Cyril Lewthwaite, who spoke excellent German, if he could explain the guard's odd reaction. Lewthwaite asked Bruce what he had said in German. Bruce obliged, whereupon Lewthwaite pointed out that "Ich ueber gebe mich" does not in fact mean "I surrender" but "I am going to be sick" (taken from a private letter to Peter Tunstall dated 5th September, 1979).[21]

Character

Over forty percent of those in the RAF were killed in action in WWII.[22] Bruce and his comrades in RAF Bomber Command would have had to have nerves of steel.[22] Notoriously short tempered (his father 'Billie' Bruce was supposed to be the 'worst tempered man in the North of England') he was described as 'as hard as nails' by his fellow Spangenberg inmate, Squadron Leader Eric Foster, in his autobiography.[23] Foster's autobiography is also an eye witness source for the Swiss Red Cross Commission escape[23] at Spangenberg Castle.

Caterpillar Club

On 9 June 1941, while navigating a Wellington bomber over the North Sea, on a mission to bomb enemy shipping on the Dutch and Belgium coast, his aircraft was shot down by, what was thought to be, two Me109’s.[24] The Me109’s were first encountered four miles from Calais.[24] Black smoke was seen coming out of the Wellington.[24] The pilot Wing Commander Roy Arnold calmly stayed at the controls of the burning Wellington, at low height, in order to keep it steady and allow the other five crew members to escape.[24] He did this in the certain knowledge that he would die doing so. He was thirty years old and married. Arnold is buried in the CWG cemetery at Blankenberge, Belgium.[25] The story of his heroic act of self-sacrifice did not emerge until after the war when the crew returned from captivity and could tell their squadron commander.

In WW2, the survival rates for bailing out into the sea were not great with roughly one third surviving[26] and despite the fact that he could not swim, Bruce baled out into the sea, hoping to allow the current to wash him south towards France and the resistance life lines that had been established there. However, motor launches were quickly despatched from the port and he was picked by the German Navy in the sea near Zeebrugge. He earned membership of the "Caterpillar Club" as a result of this exit from a "disabled aircraft" as can be seen from his wearing of the Club tie in the photo taken in 1995 at RAF Fairford (left).[note 3]

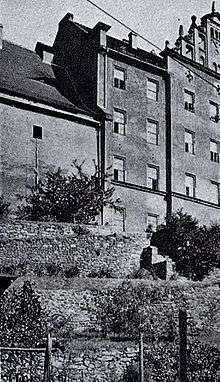

Spangenberg Castle

Bruce was first held in Oflag IX-A/H, a German prisoner of war camp at Spangenberg Castle. Spangenberg Castle (German: Schloss Spangenberg) is a schloss above the small German town of Spangenberg in the North Hesse county of Schwalm-Eder-Kreis.

Innovator of the wooden horse technique

It has been argued that Bruce and Tunstall are the original innovators of the wooden horse escape technique. Along with Eustace Newborn and Peter Tunstall, Bruce came up with the escape plan now known as "the Swiss Red Cross Commission." Tunstall, also highlights that in 1941, prior to he and Bruce planning an escape with the famed 'Swiss Red Cross Commission,' he, Bruce and a prisoner called Sammy Hoare had been digging an escape route with a wooden horse tunnel from inside the gymnasium, the wooden horse was placed roughly four feet from the wall that separated the gym from the moat.[28] The digging was a very slow process, it required the removal of spoil, bricks and stone work,[29] and was aided by other prisoners distracting the guards.[30] When Bruce and Tunstall noted the slow process they began examining the rest of the castle and left the digging to another team involving Hoare.[31] The tunnel almost reached completion but unfortunately the digging team got caught when a guard become suspicious at the large stones that were accumulating outside of the gym. The guard then called a search, and then found found the escape tunnel.[32] This wooden horse gym escape tunnel was two years prior to the famed Sagan wooden horse escape. Tunstall stated that he would like to think some of the watchers and workers who helped on their original wooden horse escape may have mentioned it from time to time;[33] and would like to think that their idea contributed to the success of the effort at Sagan.[33]

Whilst the wooden horse tunnel was being dug, Bruce and Tunstall, were planning, after they had escaped from the castle grounds, to steal an aircraft from Kassel airfield to fly to Basle Switzerland. To do this they also created Luftwaffe uniforms.[34] As the tunnel was being dug by other prisoners, Bruce and Tunstall were also in the process of exploring the castle and keeping their options open for other escape possibilities in case the tunnel route was found. At this time, Bruce and Tunstall met a new prisoner called Eustace Newborn. Newborn was a South African airman with plenty of experience flying Junkers Ju 52 and Junkers Ju 86 airplanes.[31] Needing his experience with Junkers Ju 52 airplanes, Newborn joined their escape team.[31] In the escape it was decided Tunstall, who could speak better German, would be a Feldwebel and Bruce and Newborn would be privates.[35]

Bruce and Tunstall also wanted to explore a walled off flat.[34] It was rumoured the previous occupant of this apartment was a forestry school principal who was now at the front for Germany.[34] Bruce and Tunstall eventually found a way into this flat via the attic, where from the attic they found a staircase down to the principal’s flat.[36] Bruce and Tunstall picked the locked door at the bottom of the stairs.[36] Inside the room they found escape material such as civilian clothes, officer uniforms, guns, maps, a compass, cases and stale cigars.[37] Upon sourcing these materials Bruce and Tunstall then gave up their wooden horse tunnel escape completely and left it all to Hoare. Instead they began solely focussing on the bridge and gate security.[38] Unfortunately the gate security had been increased because of a 1940 escape from the castle by three Canadians, Keith Milne, Don Middleton and Hank Wardle.[39]

Gate security

There were three companies working the castle gate. Tunstall called them, A company, B company and C company.[40] Each company worked shifts. All staff rotated their roles and sometimes a staff member would be the sentry on the castle side of the bridge who opened the gate.[40] There could be ten other posts a guard could be on.[41]

The guard commander was on the other side of the bridge away from the castle. The sentry on the castle side of the bridge was to open and close the gate on command. To let people into the castle the sentry could only open the gate after an order that could only come from the guard commander, and this order would come after the guard commander had signed the people in. To let people out of the castle, the sentry, would blow a whistle, and the guard commander would come through the gate to sign the people out, then following a command, the sentry would then open the gate.[42] Over time, they observed the C company Feldwebel was the least meticulous of the three companies and that there was no chance of escape if A company and B company had a shift, being they followed the protocol to the letter.[40]

They worked out that C company had two big flaws that could be exploited. They noticed the guard commander did not bother with the protocol when the orderlies went to the moat to feed the pigs potato peelings and rubbish from the kitchen,[43] this left the gate open. They also pinpointed the weak link in the C company team. Tunstall called the guard Blockhead. They believed he would be the least alert enough of the guards to notice their faces when they were in disguise.[44]

Escape plan

They hid all the gear needed for the escape in the sick bay.[45] They decided the escape would revolve around the three being disguised as a visiting Swiss Red Cross Commission inspection team. It was planned that on the day of escape, Tunstall would be dressed as an army Hauptmann, and Bruce and Newborn would be dressed as visiting doctors.[46] Bruce and Newborn would be very well dressed, carrying dispatch cases.[46] Bruce would also be wearing a Homburg hat and smoking a cigar.[46] Newborn would be wearing a Tyrolean hat. Underneath the attire they would be each wearing their Luftwaffe uniforms.[46]

Bruce and Tunstall estimated their escape from the castle grounds depended on these three things, pig feeding time leaving the gate to the bridge open, 'Blockhead' being on the gate and C company being on the afternoon shift.[44] They waited a long time for these conditions to occur, waiting all through August.[47] These conditions in turn rested on Blockhead failing a gullibility test.[45] The plan was for this test to be performed by a prisoner called John Milner who spoke good German.[45] The planned test was to see if Blockhead would bluff. In German, Milner would ask Blockhead if the German officer and the two Swiss doctors had left the castle?[45] If Blockhead bluffed this question, he failed the test and this would probably mean he assumed a Swiss Commission team was inside the castle. If he bluffed Milner would give a thumbs up from behind his back and this thumbs up would mean the escape plan would kick into action.[45] If ‘Blockhead,’ passed the test Milner would give a thumbs down signal from behind his back and the escape would not go ahead.

Upon the thumbs up sign the kitchen orderlies would immediately go to the door with their kitchen rubbish.[48] It was always predicted Blockhead and C company would always open the gate to the orderlies to allow the orderlies to feed the pigs with rubbish from the kitchen. At this point, when the gate was predicted to be left open by Blockhead, they devised to immerse Blockhead in to a social orchestration. They arranged for: Blockhead to be blustered and overwhelmed by his perceptions;[49] they scheduled deftly timed goon baiting from the orderlies at the gate to overwhelm him;[50] and timed for a perception of urgency from Swiss Commission inspection team and the Army Hauptmann, to rush him.[49] Prior to walking through the gate the faux Swiss commission team would be seen having chats with the British medical officers to help with the frame.[48] Upon reaching the gate they had lined up for Tunstall to state in German to Bruce, right in front of Blockhead, “Du lieber Gott, Herr Doktor, schon viertel zwei. Kommen, wir müssen weitergehen!” (“Good God, Doctor, it’s already a quarter to two. We must hurry!”).[49]

Upon exiting the castle security they planned on heading down the hill. At the bottom of the hill they planned on removing and hiding their Swiss commission clothes. They arranged to walk to the forest on their way to Kassel, dressed as Luftwaffe airmen, knowing the guards would eventually be searching for two civilians and an army Hauptmann.[51] They also organised for a white smoke signal. The white signal would come from the kitchen. This white smoke would warn Bruce, Tunstall and Newborn that the guards are now searching for them.[51]

Swiss Red Cross Commission escape

The 'Swiss Red Cross Commission' has been described as the most audacious escape of World War II. Bruce’s MC citation described it as a very clever escape. On the 3 September 1941[52] using an officer uniform and civilian clothes found in a walled off apartment belonging to the forestry principal, the three POWs simply walked out of the camp posing as a German officer (Tunstall) and two doctors (Bruce and Newborn) of a Swiss Red Cross inspection team.

The escape plan to escape the castle grounds worked. Milner tested the guard Blockhead and Milner gave the thumbs up.[53] Bruce, disguised as a doctor, conversed with the British medical officers to help frame Blockheads confusion, the orderlies goon baited Blockhead at the gate,[50] the Hauptmann (Tunstall) then marched to the gate in a hurry and stated to Bruce, “Du lieber Gott, Herr Doktor, schon viertel zwei. Kommen, wir müssen weitergehen!”[54] Blockhead even saluted the Hauptmann (Tunstall).[55] Tunstall walked by and opened the gate, Bruce and Newborn, carrying dispatch cases, with Bruce insouciantly smoking a cigar[56] (a rarity by this period of the war; and convincing evidence for the guards that the visitor was Swiss), followed him over the bridge. The guards at the other end of the bridge saluted at the Hauptmann as they made it over the bridge on their way out of the castle grounds.[57] Exiting the grounds they turned right on their way to Kassel, made their way to the bottom of the hill, removed and hid their commission disguises and marched to Kassel dressed as Luftwaffe airmen. In their escape plan there was only one thing that did not come off, at the bottom of the hill they did not see the white smoke warning that come from the kitchen warning them the security team was searching for them.[58] There were also some close calls on the way to the forest. When on an open road heading towards the forest, search parties drove past them, even asking Bruce, Tunstall and Newborn if they had seen three escapees dressed as the Swiss Commission inspection team, causing some mild anxiety.[59]

They reached the airfield the next day. At Kassel airfield they intended to steal a Junkers Ju 52, which Newborn had flown before the war, and then fly to Basle Switzerland.[60]They penetrated the aerodrome, but were discovered trying to start a Luftwaffe aircraft,[12] so they decided to find another aerodrome that was less heavily guarded near the Belgian frontier. After ten days on the road, near a small prison camp used for farm labour,[61] they were arrested by a soldier who followed them on a bike with another guard and a civillian. This soldier, who just three weeks previously worked as a guard at Spangenberg, recognised Tunstall.[62]

Bruce, Tunstall and Newborn were taken many miles to Frankenberg on the river Eder[63] and interrogated by the Gestapo. During WWII, the Gestapo were notorious for not verifying information and sending people to concentration camps.[64] Not much was known about the Gestapo in 1941.[65] Tunstall described how even the Wehrmacht, who had transported them, become anxious in the malevolent presence of the Gestapo.[65] Tunstall wanted to get out of the presence of the softly spoken Gestapo interrogator as soon as possible.[66] When Tunstall was answering his questions, Bruce and Newborn looked at Tunstall with disdain, consequentially, when Bruce and Newborn were interrogated, they instead, approached the questioning from the interrogator with disrespect.[67] Tunstall believes had the same situation happened just three years later, Bruce’s and Newborn’s approach could have been fatal.[68]

They were then sent back to Spangenberg.[69] Returned to Spangenberg, the three were each held to a long period in solitary confinement.[70] Bruce received 53 days in solitude for the Spangenberg Castle escape.[12] In Spangenberg they were not sentenced for their escape but held in preventative arrest.[70] The Senior British Officer also complained that according to the Geneva convention guidelines, the exercise yard in Spangenberg was too small, and they needed to be moved to another camp.[71]

Defying solitude

In solitary confinement, Bruce, Newborn and Tunstall were placed in three separate cells in front of, and high above, the moat they had previously escaped from.[72] Whilst they were held in confinement, they even managed to defy solitude after Bruce picked the lock on his, Newborn's and Tunstall's cell doors[73] in order that they might join him in his cell to play poker with a set of home made cards a previous occupant had left behind.[74] For the breaking of the solitude, Bruce was eventually court-martialled on the serious military charge of breaking free from arrest, the other two eventually got 5 extra days solitude. Tunstall explained he thought Bruce eventually got away with it by Bruce explaining escaping was not a court-martial offence for a POW, according to the Geneva Convention.[75] Inside of solitary, Tunstall claims, early on, there were rumours of Bruce, Tunstall and Newborn being shot.[76] After nearly eight weeks, the whole camp was made to move; Bruce, Tunstall and Newborn were rumoured to be, and expected to be, sent straight to the Colditz Straflager (punishment camp), instead, they were sent to Warburg.[76] This immediate move was a hindrance to Bruce and Tunstall as they had been formulating two more escape plans.[76] Tunstall mentions that on the journey to Warburg there was a flurry of train jumpers.[76]

Warburg prisoner of war camp

After his Spangenberg Castle escape, Bruce was eventually sent to Oflag VI-B, then in the village of Dössel (now in Warburg).[12] The Warburg camp has been described as soulless, bleak and unfinished. It roughly housed 3000 prisoners.[77]

Working party escape

Upon arrival Bruce and Tunstall immediately cased the joint and formulated escape plans.[78] They noticed the secondary gate was used occasionally to march out guarded working parties of orderlies and that the security here was lax, when compared to Spangenberg.[78] Bruce and Tunstall then created their first plan. The plan involved walking out of the camp dressed as guards. Bruce and Tunstall, then registered their new plan of escape with the Warburg escape committee. They then got working on German army uniforms to walk out through the lax security.[79] They soon faced two problems. The first problem being being they were immediately put back into solitary; and the next problem being, the escape committee changed their plans.

Their previous preventative arrest in Spangenberg amounted to almost two months, and despite the fact they had been promised that their arrest time in Spangenberg would count against any sentence in Warburg, a Major called Rademacher announced to Bruce, Tunstall and Newborn that they each would be serving 28 days in solitary.[80] This was the first immediate blow to Bruce's and Tunstall's first escape plan. The second blow occurred when the escape committee decided on adjusting their plan; they wanted their escape plan to accommodate more prisoners.[81] The escape committee new plan was to use the uniforms and the forged papers and then march out a big bogus working party.[82] Bruce and Tunstall were to be orderlies in the plan and the uniforms were to be worn by two fluent German speakers called Stevens and Lance Pope who would act as the guards of the orderlies.[83] Tunstall explains he and Bruce, accepted the change selflessly but were worried that the change in plan was too ambitious and would complicate things.[82] Still the escape committee worked on the uniforms, dummy rifles and the forged documents which were forged by John Mansel. Mansel who Tunstall described as the master forger of WWII.[81]

The first two times the worker party escape was tried it was held back at the gates via faults in the documentation. In January 1942,[12] the third time they attempted the bogus worker party, they forged the signature of the guard Feldwebel Braun.[84] This opened the gate. Though this escape was immediately hindered by the guardsman noticing Feldwebel Braun could not have signed the papers as he was on compassionate leave.[84] The guards then started firing, and the bogus workers party dispersed.[84] According to Tunstall, not one of the escape party was caught and the German uniforms, the dummy rifles and forged papers where quickly stowed away in the hides at emergency speed.[85] The German search party, though, did find a piece of green cloth which was used to make the German uniform, on the camps belongings. Bruce and Tunstall were blamed for this by Major Rademacher.[86] For this action Bruce received more time in solitary confinement.[12]

Escaping from solitary confinement

Bruce and Tunstall were sent to solitary confinement for the attempted escape with a workers party and they were given three months. They felt persecuted by Rademacher as they perceived the Major was always putting them into confinement for baseless reasons. Whilst in solitary though they still constructed more escape plans.[87] In this specific stretch of confinement, they worked out one more plan, and this set up involved an actual escape from inside the solitary confinement.[87] They wanted to break out of the camp and follow a previous route to France which was attempted by a former prisoner who had jumped on a goods train in Dössel and had evaded capture for five days. They also noted the cell block was made of a heavy timber, and that to escape from the camp with this type of timber it required adequate tools.[88] Knowing this escape needed tools, they then made a selection of hand made tools and wrapped them up. Bruce eventually hid the tools in the wood shavings in his mattress.[89]

Knowing the tools were now safe and they could pick their moment, on the morning of their planned escape, they noticed more snow had fell. They observed that this was not escaping weather and because of the conditions they had no option but to wait.[89] This wait, sadly for Bruce and Tunstall, prolonged. Whilst waiting for the weather conditions to improve, Bruce and Tunstall were ordered to pack their belongings... and they were then sent to Colditz.[89] A year later, inside Colditz, former Warburg prisoner Douglas Bader, explained the escape tools they left inside Warburg had been successfully used by another prisoner.[90]

Prisoner at Colditz

Bruce arrived in Colditz Castle, known as officer prisoner-of-war camp Oflag IV-C, on 16 March 1942. Colditz was near Leipzig in the State of Saxony.[91] It was intended to contain Allied officers who had escaped many times from other prisoner-of-war camps and were deemed incorrigible.[91] It was the only POW camp with more guards than prisoners. The Nazis regarded it as the most escape proof prison in Germany.[91] Colditz, because of the escapee prisoners it housed, eventually become thought of as an international escape academy.[92] Heavily guarded Colditz, still managed more home runs than anywhere else.[93]

Arrival and processing

On the train journey to Colditz, they had been escorted to Colditz by three privates and one NCO.[94] These guards were in turn briefed about Bruce's and Tunstall's propensity for escaping; the guards were under a threat of severe retribution if they ever escaped.[94] The guards called Colditz Sonderlager (Special Camp) and the prisoners called Colditz Straflager (Punishmant Camp).[94] When Bruce arrived at Colditz late at night and, for the first time, entered the deserted, flood lit exercise yard, on his way to the upper cells, Tunstall recollects that Bruce's first words were, "We'll get out of this bloody place too." To which Tunstall recalls he replied, "You bet."[95]

After recapture from his Spangenberg and Warburg escapes, Bruce, now in Colditz, was put in a cell whilst waiting for trial. He was charged with breaking and entering for picking a lock in a walled off part of the Spangenberg Castle; and theft of the uniform he found in the walled off room inside Spangenberg Castle; the documents also show, he was put into solitary confinement in Spangenberg Castle, and allege, Bruce kicked the cell door down whilst in his cell. The alleged action of kicking the cell door down, added a very serious charge of sabotage of state property.[96] Tunstall description of the events, differs to Bruce's charge sheet, it highlighted that no state property was broken and Bruce, Newborn and Tunstall were defying solitude after Bruce picked the locks in their solitary confinement.[97] In WWII it was generally accepted that the main rules of escaping were: don't wear German uniform; don’t use violence; and don’t engage in espionage or sabotage. It was perceived that breaking these rules could result in the prisoner facing a court-martial, and even death.[98] Bruce was clearly in trouble with regards to his charge sheet in that he had stolen a German uniform, and had been charged with an alleged sabotage of state property. The sabotage of state property being a very serious charge.[96]

To defend himself, Bruce choose a fellow Colditz prisoner, Lieutenant Alan Campbell, a trained lawyer, to advocate for him. Campbell (subsequently Baron Campbell of Alloway ERD QC (24 May 1917 – 30 June 2013)) argued that, according to King's Regulations, Bruce had a duty to escape; and using a precedent, cited a case of a German fighter pilot called Franz von Werra who had escaped, von Werra who was famed for getting the German High Command to change its policy with regards to POW's; and highlighted the fact that Bruce had never used violence. After the trial, Bruce received a moderate sentence of three months in solitary.[96]

On 21 April 1942 Bruce's commission was confirmed and he was promoted to the war substantive rank of flying officer.[99]

Tea chest escape

Bruce was the author of the famed "Tea Chest Escape" which was featured in the Imperial War Museum's 'Great Escapes' exhibition in 2004,[100] where the museum built a fascimile of the tea chest and invited children to see if they could 'escape from Colditz'. He made use of a silk map.[4] The silk escaping map Bruce used in the escape to guide him to Danzig (now Gdansk) which was sent to him by his wife concealed in a brass button of a uniform, at the behest of MI9, can be seen in the IX Squadron archive museum at RAF Marham,[101] donated to the Squadron in a handover ceremony by the Bruce family. Because of his very small stature Bruce was known ironically as the "medium-sized man"[3][4] (see camaraderie with messmates section for the origin). When a new Commandant arrived at Colditz in the summer of 1942 he enforced rules restricting prisoners' personal belongings. On 8 September 1942 POWs were told to pack up all their excess belongings and an assortment of boxes were delivered to carry them into store. Bruce immediately seized his chance and was packed inside a Red Cross packing case, three foot square, with just a file and a 40-foot (12 m) length of rope made from bed sheets. Bruce was taken to a storeroom on the third floor of the German Kommandantur and that night made his escape.[102] The next morning the castle was visited by General Wolff, officer in charge of POW army district 4.[16] He inspected the camp and found everything to his satisfaction.[16] Fortunately for the camp commandant, as Wolff was driven away, his back was turned to the southern face of the castle. If he had turned his head he would have seen a length of blue and white checked (bedsack) rope dangling from a remote window.[16] It was, however, eventually noticed by a hausfrau (housewife) in the town, who quickly reported it to the duty officer.[16][103] When the German guards entered the storeroom they found the empty box on which Bruce had, in yet another of his pranks, inscribed in chalk:

| “ | "Die Luft in Colditz gefällt mir nicht mehr. Auf Wiedersehen!"[102] | ” |

| — Dominic Bruce | ||

Translated this means: "The air in Colditz no longer agrees with me. See you later!"[4] Pat Reid explained it was almost tempting providence of Bruce to write Auf Wiedersehen on the box instead of writing good bye.[4] Bruce travelled 400 miles to Danzig; the furthest distance he ever made in all his escapes.[104] To get to Danzig, he slept rough,[12] and he travelled by bicycles which he stole from outside village churches during Mass. Whilst travelling to Danzig, Bruce was temporarily recaptured in Frankfurt-on-Oder, but escaped prior to interrogation.[12] In Danzig, one week later, he was eventually caught trying to stow away on a Swedish Freighter.[104] When he returned to Colditz, Bruce received more time in solitary.[12]

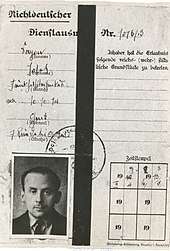

Triple identity ploy

He is thought to be the inventor of the 'triple identity' ploy for use when captured, which he explains in the Imperial War Museum Sound Archive tapes.[17][18][note 4] The triple identity meant that he had three personae; his real identity as himself, the identity shown on his false ID papers; and another identity that he would only reveal under pressure. When he was captured, he was disguised as a Belgian Gastarbeiter or 'guest worker' named Josef Savon (his false ID is still in the possession of the Bruce family) another example of Bruce's fondness of disguises. In his autobiographical book, 'The Tunnellers of Sandborstal' (Robert Hale, 1959), Lieutenant Commander John 'Bosun' Chrisp MBE RN said that "Bruce's adventures in various corners of occupied Europe read like John Buchan (author of 'The Thirty Nine steps') at his most melodramatic" and that Bruce "can claim to be the most ingenious and unlucky escaper of the war."[5] The use of the Josef Savon disguise is also another example of Bruce's predilection for pranks, as Josef Savon translates into 'Joe Soap'. In 1944, Joe Soap was RAF slang for a legendary airman who carried the can.[note 5]

When captured he pretended to break down and admitted he was in fact Flight Sergeant Joseph Lagan. Lagan was his brother in law and so Bruce could answer detailed questions about his service record etc. Initially the delighted Germans believed him and were ready to send him to a Stalag or 'other ranks' camp.[17][18] Under the Geneva Convention, other ranks (unlike officers) could be made to work; and were often taken outside camps on working parties; from which it was easy to escape. His story when captured was that he had jumped from a British plane over Bremen and arrived in Danzig on a stolen bicycle;[4] his bicycle, unbeknown to Bruce, had a local number on it.[4] Bruce was then sent to the RAF camp at Dulag Luft near Oberursel.[4] Whilst at the camp, the Germans had already requested a specialist Gestapo interrogator to come from Berlin, who was to recognise Bruce.[4][17][18] When he arrived he took one look at the supposed Flight Sergeant Lagan and said "Ah, Captain Bruce, how nice to see you again". This was the second time he had interrogated Bruce (whom the Germans habitually addressed as 'Captain'). Under heavy guard, Bruce was taken by train back to Colditz. On the overheated train, the guard detail fell asleep and Bruce tried to escape once again, but was prevented by a watchful officer.[17][18]

Aiding an escape from solitary confinement

The 'Tea Chest Escape' made Bruce the first prisoner to escape from both Spangenberg Castle and Colditz Castle. He was soon to be joined by Howard 'Hank' Wardle MC[106] who would soon escape from Colditz with Captain Pat Reid, Major Ronald B. Littledale, and Lieutenant Commander L. W. Stephens. Wardle had also escaped from Spangenberg Castle.[107][note 6] This escape by Wardle, Reid, Littledale and Stephens was aided by reconnaissance from Bruce. Pat Reid explained that whilst Bruce was in solitude, he got a message smuggled to Bruce, via his food. Reid wanted Bruce to give him some detail about the German Kommandantur of the castle.[108] In due course Reid received a return message from Bruce.[108] This message gave him information about the specific unused staircase, the top floors, and importantly, how the door to this staircase was in full view of the Kommandantur sentries, and how this door was put into shadow by the flood lights.[108] On 14 October 1942, in the Kommandantur cellar escape, they all used Bruce's information and tried to get the staircase door open with a dummy key. Unfortunately the dummy key failed. This worked out though; as with their contingency plan, using the shadow, they slowly worked their way to the Kommandantur cellar to which they where to escape from.[109]

Musketoon witness

In October 1942 seven captured commandos were processed inside Colditz and sent to solitary confinement. These commandos had previously been involved in the Operation Musketoon raid. Inside the cells Peter Storie-Pugh, Dick Howe and Bruce had managed to have conversations with them.[110]

On 13 October 1942 the commandos were removed from Colditz and taken to the SS-Reichssicherheitshauptamt (RHSA) headquarters in Berlin, where they were interrogated one by one by Obergruppenführer Heinrich Müller.[111] They remained in Berlin until 22 October, when they were taken to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp. On the next day, 23 October, they were all shot in the back of the neck and their bodies cremated.[112] These commandos were the first to fall victim to Adolf Hitler's Kommandobefehl (Commando Order) issued on 18 October 1942, which called for the execution of all commandos after capture.

In 1964 Stephen Schofield interviewed Bruce for his book 'Musketoon: commando raid, Glomfjord, 1942' (University of Michigan), revealing that while in the solitary confinement cells, Bruce managed to make contact with Captain Black DSO, leader of Operation Musketoon, the Anglo-Norwegian commando raid mounted against the German-held Glomfjord power plant in Norway. Bruce was the last British person to speak to Black before he (and six comrades) was murdered in Sachsenhausen concentration camp.[110] The official German story given to the Red Cross was that the seven men had escaped and not been recaptured, and Colditz Oflag IVC were instructed to return any letters to their senders marked Geflohen (escaped),[110] but Bruce's testimony was sent from Colditz to MI5 in London and ensured that the British authorities knew the truth.[113]

Bruce was promoted again, to flight lieutenant, on 20 January 1943.[114]

Escaping after August 1943

By 1944 escaping was becoming tougher and more risky. Walter Morison explained that by August 1943 most of the loopholes to escape in the castle had been exploited;[115] making escaping even harder. By spring 1944 escaping got more risky. Contrary to the Geneva convention the use of force had been debated inside the German mess for years. Oberstleutnant Prawitt, the Kommandant and Staff Paymaster Heinze were keen on using it on repeat offenders,[116] such as Bruce. As was the Major Amthor, the new second in command, who had joined the mess in May 1943. Amthor was a young keen Nazi and had constantly tried to influence for the use rough measures.[116] Amthor and Prawit were hated by the prisoners that when ever they entered the court yard they were whistled and howled at.[116] Püpke was not a Nazi and was even given a courteous reception during Appell in the summer of 1944.[117] In late March 1944, Hitler had disregarded the Geneva Convention with regards to POW's. The punishment for escape now carried a punitive risk of execution.[note 7] Bruce made two further escape attempts in 1944; on 19 April and on the 16 June.

On his 19 April escape he cut through bars on north side of the castle and reached the wire fence before being detected.[119] After Bruce was seen by the sentries, Bruce was then fired at by rifle and machine guns.[120] Knowing he did not stand a chance, Bruce surrendered. When surrendering, Bruce, to the amusement of the German guards, instead of yelling, "Ich gebe auf" ("I give up"), in a faux pas yelled, "Ich ueber gebe mich" ("I feel sick.").[120]

Drain escape

On 16 June escape, Bruce, Major R. Lorraine and John "Bosun" Chrisp tunnelled through sewers into an old well in the German yard that had a pipe that lead into the river, but were again detected.[121] The sewage escape route that lead to the manhole covered well, was found via the help of earlier tunnelling and reconnaissance by the Poles, along with the help of Jack Best (also of the Colditz Cock fame) and Mike Harvey.[122] Best and Harvey had frequented with the Poles in their time as ghost prisoners and had participated in their tunnel digging.[122] Best hated the tunnel in his days as a ghost prisoner, claiming your arse always got wet with cold waste water.[122] Though Best noted the Poles were very proud of their dangerous tunnel.[122] One prisoner claimed the tunnel even had a 'terrifying' electrical cable that ran inside the damp conditions.[123] When the Poles left the castle, the tunnel was bought by a party for 100 cigarettes.[20] Sometime after 1941, the Poles had dug a key hole through a rock that itself lead onto the main sewer system. In 1944, Bruce, Chrisp and Lorraine, surveyed the tunnel, whilst Dick Howe ensured the kitchen, showers and toilets were off limits to other POW's.[123] When they entered that hole they found the main sewage system lead to the well;[124] the well they were soon to be captured in.[123] They then returned to base, to have the castle’s doctor brush them with iodine, and to collect some tools which would help them hammer spikes into the well wall.[123]

When they returned to the well, Lorraine, tied by a rope, was lowered to the bottom of the well, in what was low tide, and began hammering in the spikes.[123] There were three manhole covers around the German Kommandantur that were within 50 yards of each other.[125] At the archway halfway outside of the castle, a guard heard noises beneath his feet, whilst he was standing near one of the manhole covers.[125] Upon hearing the noise, the guard gave a shout to the riot squad and security officer; and an immediate order was made to open up the three manhole covers.[125] Staff Paymaster Heinze walked past one of the covers and spotted them and spat at them calling them ”stinking swines.”[125] Later, for this abuse, the Senior British Officer (SBO), obtained an apology.[125] A guard also threatened to shoot Bruce, Lorraine and Chrisp whilst they were in the uncovered drain.[123] The Germans then called an immediate Sonderappell. and after this Appell, an effort was made by the escape committee to save the hundred yard tunnel from inside the ex-Polish long-room, unluckily, for the escape committee, the Appell had given the Germans enough time to uncover the rest of the shaft.[126]

Faced by a firing squad

When Bruce, Lorraine and Chrisp were caught, according to Chrisp, Bruce, became spokesman for the three in the interrogation.[121] As spokesman he declined to answer to Eggers, on three separate times, as to where the entrance to their escape tunnel was. For this the three men where placed in front of a wall and faced by a firing squad; though Eggers did not give an order to fire.[121] Chrisp explained, in his IWM tapes, the three were then put in the civilian cells outside the castle for two or three weeks; whereby after the solitary confinement, the Senior British Officer informed them that the Komandment had fined them £100 each for damaging the drains.[20] Bruce, upon hearing the fine, made a counter claim, and he billed the Kommandant for £200 each for their service of cleaning the drains that had not been cleaned for 300 years.[20]

The Germans were getting tired of escaping by a number of the prisoners, and in the summer of 1944, each POW camp was given a flyer reinforcing the fact the Germans were taking escaping very seriously. The notice referenced that breaking out was no longer a sport, and that you will be shot on escape.[127] The notice was up inside the Colditz prisoner yard by the 8 August 1944.[117] Eventually, orders came (via MI9 and the Senior British Officer) that all escapes were forbidden and so Bruce and his comrades had to sit out the war until the liberation came in April 1945.

Liberated from Coldtiz

Bruce was eventually liberated on 16 April 1945 by the US Army.[12] In a 1973 interview, Bruce described the day of liberation as, pure wild west, getting guns, going off to liberate chickens and wine, and having a great time.[128]

In the IWM tapes Bruce describes the scene. The first GI through the castle gates heard a voice from a second floor window. "Take that man's sidearm" the voice ordered. The GI duly disarmed a German guard. "Tie it onto this piece of string" the voice said. The GI complied. The pistol (which is still in the possession of the Bruce family) was hauled up the castle wall and disappeared into the window. Bruce (who, like the other prisoners and Germans alike, had been at near starvation levels during the last months of the war) went directly to the castle kitchens and put the gun to the head of a German cook and demanded a chicken. Sadly, there were none to be had. Bruce was flown to England to meet the two small boys (and the wife) he had not seen since 1941 outside Victoria railway station in London.[17][18]

Military Cross

In October 1946 he was awarded the Military Cross (MC) for his escape attempts,[129][130] making him the only person ever to be awarded both the Military Cross and the Air Force Medal.[131][note 8]

- Citation

Later life

Personal life

After the war, Bruce and his wife Mary, settled in Sunbury-on-Thames in Surrey.[12] They brought up nine children, six boys and three girls.[104] One of his sons, Brendan,[17] is a communications executive, and a former Director of Communications to Prime Minister Thatcher. The Bruce family report that his nickname amongst the family (which was given to him by his Italian son-in-law, Piero Carloni), was 'Il Cavaliere' ('the knight') due to his Papal knighthood .

Education

.jpg)

In 1946 Bruce became a student at Corpus Christi College, Oxford, reading Modern History, and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1949.[1] He completed what was known as War Degree (7 terms) and was awarded a Master of Arts degree in 1953.

Bruce served as an Adult Education Tutor at Bristol University, 1949–50. He was Assistant Secretary of the University Committee, Adult Education HM Forces, 1950–53; Further Education Officer, Surrey County Council, 1953–59; Principal, Richmond Technical Institute, 1959–62. Bruce became the Founding Principal of Kingston College of Further Education, 1962–1980.[133] There was significant interest at the time for this important new position and the short list consisted of Bruce, a distinguished Royal Navy Captain and an Army Brigadier (i.e. a 'one star' general). Bruce's quick wit was responsible for his appointment. When he entered the interview room, the Chairman of the Panel was reading his CV and looked up at him in astonishment saying "it says here that you have nine children. Are they all yours?" (thinking that some were perhaps stepchildren). "So my wife assures me" came Bruce's imperturbable reply.

Executive and advisory roles and honours

In civic and charitable bodies Bruce also acted as:

- Chairman of the Further and Higher Education Committee of the Archdiocese of Westminster

- Schools Officer, Archdiocese of Westminster, 1978–80.

- Committee member of the Association of Principals of Colleges and member of its Regional Advisory Council

- Chairman of the General Commissioners of Income Tax, Spelthorne Division

- Education Advisor to the RAF Benevolent Fund.

Bruce was made an Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE) by Queen Elizabeth II in 1989 for his services to Education.[12] He was also awarded the Pontifical Equestrian Order of St. Gregory the Great (Latin: Ordo Sancti Gregorii Magni) by Pope John Paul II.

Death and legacy

Dominic Bruce died on 12 February 2000 in Richmond, Surrey, England. He was survived by Mary Brigid Bruce (died 15 June 2000) and his six sons and three daughters.[104]

In 2015 his medal group (unique in that he is the only person in British military history to be awarded both the Military Cross and the Air Force Medal) was donated by his family to the Ashcroft Trust for the benefit of the RAF Benevolent Fund and the British Red Cross, the latter having kept him alive in Colditz by the sending of regular food parcels.

Filmography and sound

Portrayals in film and television

In the BBC TV series Colditz (1972–74), which chronicled the lives of the Allied prisoners of war held in the castle, one of the characters portrayed was Flight Lieutenant Simon Carter (played by David McCallum) - Carter was a young, upstart, hot-headed RAF officer who enjoys goon-baiting and is very impatient to escape. The fictional Carter closely resembles Bruce.[134] In the episode, from series one, 'Gone Away, part 1', first shown 18 January 1973, the 'Tea Chest Escape' was re-enacted.[12]

Colditz, a 2005 British two-part television miniseries produced by Granada Television for ITV, written by Peter Morgan and directed by Stuart Orme, features a fictionalised account of an actual event when three inmates; Dick Lorraine, John 'Bosun' Chrisp, and the 'Medium Sized Man', Dominic Bruce attempted to escape using the castle sewers. In reality the escape team were discovered when they attempted to exit a manhole. The Germans threatened to throw grenades down into the sewer chamber and, as the escapers could not reverse back up the sewer pipe, they were forced to surrender. They were immediately put in front of a firing squad, but unlike the fictional TV account, the guards did not fire. Just before the order was to be given, Bruce lost his temper and approached the officer in charge, Eggers, saying "you can shoot us, but after the War we'll hang you". Eggers stood the squad down.

The 'Red Cross Commission' escape from Spangenberg provided the plot for the 1961 film, 'Very Important Person' although no acknowledgement was made by the producers at the time. In the film, James Robertson Justice also escapes disguised as a Swiss civilian Commissioner, just as Bruce had done in real life.

Documentaries

The BBC series Colditz (1972–74), was such a success that it was quickly repeated. In order to make up the episodes to a sixty minute slot (the BBC had hoped to sell the series to the USA, hence the use of Robert Wagner, so they had to be only fifty minutes in length to include commercials) a select group of six Colditz escapers were interviewed individually by the famous war correspondent Frank Gillard and shown immediately after the repeat programmes were broadcast. Bruce was one of the interviewees. The documentary series was called Six from Colditz, and Bruce's interview was listed in 17 April 1973,[135] and also on 17 January 1974 in the Radio Times.[136][note 9] Transcripts of Bruce’s interview, with Gillard, which aired in 1973, exist.[135]

From 1996 to 2006 the Colditz Society created a selection of filmed interviews with many Colditz survivors. Bruce was recorded and is referenced in the collection. These interviews are now museum artefacts and are held in the Imperial War Museum.[137]

Notes

- ↑ The Newcastle law courts are now on the Quayside. The courts Bruce would have frequented in his youth would have been the city's Moot Hall courthouse. The Moot Hall operated as law courts from 1812 to 1998.[6]

- ↑ Prior to the war, in 1938 when the incident took place, Bruce, new to his career, was only a Leading Aircraftman (LAC); therefore he received the Air Force Medal, rather than the Air Force Cross (AFC) which was given only to officers. This is explained in Pete Tunstall's book, 'The Last Escaper.' In the book Tunstall argues this was needless discrimination against lower ranks.[14]

- ↑ The Caterpillar Club is an informal association. The only requirement to join is that you have survived by using a parachute when jumping from a stricken aircraft.[27] In his career, documents show Bruce qualified not just in 1941, but in 1938.

- ↑ Bruce was captured in 1941. The allies did not start survival training until 1943.[26] This highlights that Bruce was using an initiative, without any official training, with regards to the triple identity ploy. This can also give plausibility to the understanding that Bruce, if found not to be the first, was one of the first few, captured airmen, to ever use the 'triple identity ploy' technique.

- ↑ For the WW2 definition the etymologist Michael Quinion quoted the Royal Air Force Quarterly: "Joe Soap was the legendary airman who carried the original can. He became a synonym for anyone who had the misfortune to be assigned an unwelcome duty in the presence of his fellows, or to be temporarily misemployed in a status lower than his own. “I’m Joe Soap,” he would say lugubriously, and I’m carrying the something can.” Royal Air Force Quarterly, 1944." Quinion then explains, "“Something” may be read as a polite substitute for a more forceful epithet."[105]

- ↑ Bruce and Wardle are thought to be the only two documented prisoners who have escaped from Spangenberg Castle and Colditz Castle.

- ↑ On 25 March 1944, going against objections of many senior officers, Hitler ordered the execution of 50 allied troops who had escaped from Stalag Luft III.[118] This highlighted Hitler was no longer following the Geneva Convention with regards to POW's. This precedent meant escaping from any POW camp, after 24 March 1944, carried a significant risk of execution.

- ↑ In 1993 the Air Force Medal was discontinued and replaced by the Air Force Cross(AFC) medal.[132] This means Bruce will be continuously unique in that he will be the only man to have received the Military Cross and the Air Force Medal combination.

- ↑ Pre 1980 the BBC had a practice of wiping. This interview may be lost.

Footnotes

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hunt (1988), p. 443.

- 1 2 Air Ministry (1941), p. 1371: 'Acting Flight Sergeant. 2oth Jan. 1941. (Seniority 8th Jan. 1941.) 522098 Dominic BRUCE, A.F.M. (45272).'...

- 1 2 Kerr (2011), Colditz Castle: 'Dominic Bruce, a British officer, known as 'Medium-sized Man'...

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Reid (2015), p. 150.

- 1 2 Chrisp MBE RN (1959):'can claim to be the most ingenious and unlucky escaper of the war.'

- ↑ Chronicle Crown Court Staff (2018):'Newcastle’s Moot Hall previously heard all cases before Newcastle Crown Court was built.'...

- ↑ Bruce (1999), Visits to law courts.

- ↑ Tunstall (2014), Location 2863.

- ↑ Moss (1975), p. 320.

- ↑ BAAA (1937).

- ↑ BAAA (1938).

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Battle (2018).

- ↑ Air Ministry (1939), p. 3874: 'Air Force Medal...; 522098 Leading Aircraftman Dominic BRUCE.'...

- 1 2 3 Tunstall (2014), Chapter 8 - "Whats the plan?".

- 1 2 3 4 5 Reid (2015), p. 149.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Bruce (1999).

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Windle (2006).

- ↑ Eggers (R). Gee (H) (Author) (1961).

- 1 2 3 4 Wood (1996), Reel 3, 20:00s - 29:00s.

- ↑ Bruce (1979).

- 1 2 Veterans SA (2016).

- 1 2 Foster (1992).

- 1 2 3 4 Thorburn (2006), p. 54.

- ↑ CWGC (1941):'Roy George Claringbould... Service Number 29198...'

- 1 2 RAF St Mawgan (2015).

- ↑ Irvin (2018).

- ↑ Tunstall (2014), Location 2899.

- ↑ Tunstall (2014), Location 2909.

- ↑ Tunstall (2014), Location 2904.

- 1 2 3 Tunstall (2014), Location 2912.

- ↑ Tunstall (2014), Location 3028.

- 1 2 Tunstall (2014), Location 3031.

- 1 2 3 Tunstall (2014), Location 2922.

- ↑ Tunstall (2014), Location 2920.

- 1 2 Tunstall (2014), Location 2947.

- ↑ Tunstall (2014), Location 2951.

- ↑ Tunstall (2014), Location 2959.

- ↑ Tunstall (2014), Location 3822.

- 1 2 3 Tunstall (2014), Location 2969.

- ↑ Tunstall (2014), Location 2981.

- ↑ Tunstall (2014), Location 2961.

- ↑ Tunstall (2014), Location 2972.

- 1 2 Tunstall (2014), Location 2977.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Tunstall (2014), Location 2997.

- 1 2 3 4 Tunstall (2014), Location 2982.

- ↑ Tunstall (2014), Location 3027.

- 1 2 Tunstall (2014), Location 3006.

- 1 2 3 Tunstall (2014), Location 3009.

- 1 2 Tunstall (2014), Location 3048.

- 1 2 Tunstall (2014), Location 3023.

- ↑ Rollings (2003), p. 185.

- ↑ Tunstall (2014), Location 3045.

- ↑ Tunstall (2014), Location 3057.

- ↑ Tunstall (2014), Location 3058.

- ↑ Tunstall (2014), Location 3054.

- ↑ Tunstall (2014), Location 3062.

- ↑ Tunstall (2014), Location 3070.

- ↑ Tunstall (2014), Location 3084.

- ↑ Tunstall (2014), Location 3115.

- ↑ Tunstall (2014), Location 3279.

- ↑ Tunstall (2014), Location 3317.

- ↑ Tunstall (2014), Location 3322.

- ↑ Tunstall (2014), Location 4166.

- 1 2 Tunstall (2014), Location 3329.

- ↑ Tunstall (2014), Location 3336.

- ↑ Tunstall (2014), Location 3337.

- ↑ Tunstall (2014), Location 3344.

- ↑ Tunstall (2014), Location 3345.

- 1 2 Tunstall (2014), Location 3412.

- ↑ Tunstall (2014), Location 3385.

- ↑ Tunstall (2014), Location 3409.

- ↑ Tunstall (2014), Location 3471.

- ↑ Rollings (2004), p. 210.

- ↑ Tunstall (2014), Location 3486.

- 1 2 3 4 Tunstall (2014), Location 3488.

- ↑ Tunstall (2014), Location 3494.

- 1 2 Tunstall (2014), Location 3501.

- ↑ Tunstall (2014), Location 3507.

- ↑ Tunstall (2014), Location 3528.

- 1 2 Tunstall (2014), Location 3535.

- 1 2 Tunstall (2014), Location 3541.

- ↑ Tunstall (2014), Location 3554 - 3561.

- 1 2 3 Tunstall (2014), Location 3595.

- ↑ Tunstall (2014), Location 3610.

- ↑ Tunstall (2014), Location 3616.

- 1 2 Tunstall (2014), Location 3704.

- ↑ Tunstall (2014), Location 3714.

- 1 2 3 Tunstall (2014), Location 3732.

- ↑ Tunstall (2014), Location 3742.

- 1 2 3 Tyson (2001).

- ↑ Reid (2015), p. 345.

- ↑ Tunstall (2014), Location 3993.

- 1 2 3 Tunstall (2014), location 3756.

- ↑ Tunstall (2014), location 3793.

- 1 2 3 The Timaru Herald Staff (2013).

- ↑ Tunstall (2014), location 3471.

- ↑ Morison (2003).

- ↑ Air Ministry (1942), p. 1753: 'and to be Fig. Offs...; D. BRUCE, A.F.M. (45272). 2oth Jan. 1942. (Seny. 8th Jan. 1942.)'...

- ↑ IWM Great Escapes Exhibition (2004).

- ↑ RAF Marham Museum (2018).

- 1 2 Chancellor (2001).

- ↑ Kemble, Mike. "Colditz Castle". Second World War.org.uk. Archived from the original on 27 December 2012. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 Honan (2000).

- ↑ Quinion (2007): '...Royal Air Force Quarterly, 1944. “Something” may be read as a polite substitute for a more forceful epithet.'

- ↑ Reid (2015), p. 161.

- ↑ Reid (2015), p. 21.

- 1 2 3 Reid (2015), p. 158.

- ↑ Reid (2015), pp. 158-161.

- 1 2 3 Reid (2015), p. 154.

- ↑ Schofield (1964), p. 141.

- ↑ Schofield (1964), p. 143.

- ↑ Schofield (1964), p. 135.

- ↑ Air Ministry (1943), p. 1744: 'Flight Lieutenants...; D. BRUCE, A.F.M. (45272). 2oth Jan. 1943. (Seny. 8th Jan. 1943.)'...

- ↑ Wilson (2000), p. 143.

- 1 2 3 Chancellor (2001), p. 301.

- 1 2 Reid (2015), p. 222.

- ↑ Klein (2014).

- ↑ Chancellor (2001), p. 403.

- 1 2 Thorburn (2006), p. 55.

- 1 2 3 Chancellor (2001), p. 300.

- 1 2 3 4 Chancellor (2001), p. 298.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Chancellor (2001), pp. 298-301.

- ↑ Chancellor (2001), p. 299.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Reid (2015), p. 220.

- ↑ Reid (2015), p. 221.

- ↑ Wilson (2000), pp. 143-144.

- ↑ Mackenzie (2006), p. 377.

- 1 2 Air Ministry (1946), p. 4991: 'Military Cross...; Flight Lieutenant Dominic BRUCE, A.F.M. (45272). Royal Air Force, No. 9 Squadron. Flight Lieutenant Bruce...'...

- ↑ TOW (2018), Military Cross (MC): '"Flight Lieutenant Bruce was shot down over Zeebrugge in June, 1941, and picked up by a German vessel. After an unsuccessful tunnel attempt in July, 1942, Flight Lieutenant Bruce and two companions made a very clever escape from Spangenburg in September, 1942, disguised as a German civilian commission and officer escort. They reached Cassel aerodrome hoping to find a Junkers 52 - the only German aircraft they knew how to fly - and, finding none of this type on the field, they decided to make for France but were caught several days later near Frankenberg. After this attempt, Flight Lieutenant Bruce was transferred to Warburg. From there he made several attempts to escape, the most successful being in January, 1942, when three men masqueraded as a German guard escorting a party of British orderlies. For this, Flight Lieutenant Bruce received three months in cells from which he attempted to escape with the aid of a dummy key, but was prevented by the bad weather. In September, 1942, he escaped from Colditz in an empty crate and made for Danzig. He was captured ten days later at Frankfurt-on-Oder, but escaped while awaiting interrogation. He reached Danzig and was arrested trying to board a troop ship. Flight Lieutenant Bruce continued to try every possible means of escape, with varying degrees of success, throughout his captivity making about seventeen attempts in all. He was liberated from Colditz in April 1945.'

- ↑ Battle (2018), Paragraph two: 'the only airman ever to have been awarded both the Air Force Medal (AFM) and the Military Cross (MC).'...

- ↑ GM-L (2018): 'the Air Force Medal (AFM),... were also discontinued from September 1993...'

- ↑ Bradshaw, Benjamin & Cotterell (1999).

- ↑ "Theme Time: Robert Farnon - Colditz". So It Goes... 23 October 2017. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- 1 2 Mackenzie (2006), p. 382.

- ↑ Radio Times (1974).

- ↑ Colditz Society (2006).

Sources

- Books

- Bradshaw, P.; Benjamin, B.; Cotterell, A. (1999). Kingston College: A Brief History. Kingston, Surrey: CDT Printers.

- Chrisp MBE RN, John 'Bosun' (1959). 'The Tunnellers of Sandborstal'. United Kingdom: Robert Hale.

- Chancellor, Henry (2001). Colditz: The Definitive History. London, UK: Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 978-0-34079-494-4.

- Eggers (R). Gee (H) (Author) (1961). Colditz. The German Story. Translated and edited by Howard Gee. United Kingdom: Robert Hale.

- Foster, Eric (1 February 1992). Life Hangs by a Silken Thread: An Autobiography by Squadron Leader. England: Astia Publishing. ISBN 978-0951898307.

- Hunt, Philip A. (1988). Biographical Register 1880-1974 Corpus Christi College (University of Oxford). Oxford, England: The College. ISBN 9780951284407.

- Kerr, Gordon (2011). Fugitives: Dramatic Accounts of Life on the Run. England: Canary Press eBooks. ISBN 9781907795763.

- Mackenzie, S. P. (2006). The Colditz Myth: British and Commonwealth Prisoners of War in Nazi Germany (illustrated, reprint ed.). United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199203079.

- Ray, David (2004). Colditz: A Pictorial History. London, UK: Caxton Editions. ISBN 1-84067-156-4.

- Reid, P. R. (1954). The Colditz Story. London, UK: Pan Books.

- Reid, P. R. (1984). Colditz: The Full Story. New York: St. Martin's. ISBN 0-312-00578-4.

- Reid, P. R. (2003). The Latter Days at Colditz. London, UK: Cassell Military Paperbacks. ISBN 0-304-36432-0.

- Reid, P. R. (2015). Colditz: The Full Story. New York: Voyageur Press. ISBN 9780760346518.

- Rollings, Charles (26 November 2003). Wire and Walls: RAF Prisoners of War in Itzehoe, Spangenberg and Thorn 1939-42. United Kingdom: Ian Allan Publishing. ISBN 978-0711029910.

- Rollings, Charles (1 September 2004). Wire and Worse: RAF Prisoners of War in Laufen, Bibarach, Lubeck and Warburg 1940-42. 2. United Kingdom: Ian Allan Publishing. ISBN 978-0711030503.

- Schofield, Stephen (1964). Musketoon: commando raid, Glomfjord, 1942 (First ed.). Michigan: Cape (University of Michigan).

- Thorburn, Gordon (2006). Bombers,First and Last. United Kingdon: Robson. ISBN 9781861059468.

- Tunstall, Peter (2014). The Last Escaper. London, UK: Duckworth. ISBN 978-0-71564-923-7.

- Wilson, Patrick (11 September 2000). The War Behind the Wire. United Kingdom: Pen and Sword. ISBN 9780850527452.

- Letters

- Bruce, Dominic (5 September 1979). "Colditz..." (Letter). Letter to Peter Tunstall.

- Magazines

- Moss, Peter W. (August 1975). "Aeroplane Biography No.4 - Handley Page Harrow K6940". Air Pictorial. Vol. 37 no. 8.

- Radio Times (21 January 1974). "Listings". Radio Times. Vol. 202 no. 2619. United Kingdom: BBC (published 17 January 1974). pp. 12–13. Retrieved 17 September 2018.

- Museum artefacts

- Bruce, Brendan (1999). "Bruce, Dominic (Oral history); (Catalogue number 22332)". iwm.org.uk. Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 1 July 2012.

- Colditz Society (2006). "Collection of Interviews With Colditz Survivors (Film number:6636)". iwm.org.uk. Colditz Society (Production sponsor). Retrieved 26 September 2018.

- IWM Great Escapes Exhibition (2004). "Great Escapes (exhibition); (Catalogue number Art.IWM PST 20321)". iwm.org.uk. Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 20 August 2018.

- RAF Marham Museum (2018), Dominic Bruce Silk Map, Norfolk and Suffolk: Norfolk and Suffolk Aviation Museum (RAF Marham Museum)

- Windle, Dave (1 June 2006). "Bruce, Dominic (Oral history); (Catalogue number 29172)". iwm.org.uk. Imperial War Museum; Colditz Society. Retrieved 1 July 2012.

- Wood, Conrad (13 September 1996). "Chrisp, John 'Bosun'(Oral history)(Catalogue number 16843)"". iwm.org.uk. Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 24 September 2018.

- Newspapers

- Air Ministry (8 June 1939). "Supplement: 34633". The London Gazette (Supplement). London: The London Gazette. Retrieved 9 August 2018.

- Air Ministry (7 March 1941). "Supplement: 35097". The London Gazette (Supplement). London: The London Gazette. Retrieved 9 August 2018.

- Air Ministry (21 April 1942). "Supplement: 35531". The London Gazette (Supplement). London: The London Gazette. Retrieved 9 August 2018.

- Air Ministry (13 April 1943). "Supplement: 35981". The London Gazette (Supplement). London: The London Gazette. Retrieved 9 August 2018.

- Air Ministry (8 October 1946). "Supplement: 37750". The London Gazette (Supplement). London: The London Gazette. Retrieved 9 August 2018.

- Battle, Ken (2 July 2018). "Flt. Lt. Dominic Bruce, AFM, MC, OBE". Sunbury Matters & Sunbury; Shepperton Local History Society. Sunbury: villagematters.co.uk. Retrieved 9 August 2018.

- Chronicle Crown Court Staff (8 August 2018). "Newcastle Crown Court". Chronicle. Newcastle: chroniclelive.co.uk. Retrieved 8 August 2018.

- Honan, William H. (4 March 2000). "Dominic Bruce, 84, Briton Who Tried to Escape Nazis 17 Times". The New York Times. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- The Timaru Herald Staff (6 July 2013). "Colditz prisoner became a top lawyer". The Timaru Herald. New Zealand: pressreader.com. Retrieved 19 August 2018.

- Websites

- BAAA (25 March 1937). "Crash of a Handley Page H.P.54 Harrow I in Napsbury". Bureau of Aircraft Accidents Archives. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- BAAA (6 October 1938). "Crash of a Handley Page H.P.54 Harrow II in Kirk Smeaton". Bureau of Aircraft Accidents Archives. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- CWGC (9 June 1941). "Casualty Details: Arnold, Roy George Claringbould; Service Number 29198". www.cwgc.org. Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Retrieved 27 November 2017.

- GM-L (2018). "Decorations & Medals". gm-league.com. The Gallantry Medalists' League. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- Irvin (2018). "Caterpillar Club". irvingq.com. irvingq. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- Klein, Christopher (25 March 2014). "Remembering "The Great Escape," 70 Years Ago". history.com. history.com. Retrieved 18 August 2018.

- Mason, Amanda (6 February 2018). "Who's Who In An RAF Bomber Crew". iwm.org.uk. Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

- Morison, Walter (23 July 2003). "Colditz 1945: The Last Days". bbc.co.uk. BBC. Retrieved 26 September 2018.

- Quinion, Michael (18 August 2007). "Joe Soap". worldwidewords.org. worldwidewords.org. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- RAF St Mawgan (2015). "RAF Survival Training". RAF St Mawgan. Archived from the original on 6 August 2015. Retrieved 24 August 2018.

- TOW (2018). "Bruce, Dominic". www.tracesofwar.com. Traces of War. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- Tyson, Peter (2001). "Escaping Colditz". pbs.org. NOVA Online. Retrieved 1 September 2018.

- Veterans SA (10 June 2016). "The legacy of Bomber Command". anzaccentenary.sa.gov.au. gov.au. Retrieved 19 September 2018.