Deforestation in Brazil

Brazil once had the highest deforestation rate in the world and in 2005 still had the largest area of forest removed annually.[1] Since 1970, over 700,000 square kilometers (270,000 sq mi) of the Amazon rainforest have been destroyed. In 2012, the Amazon was approximately 5.4 million square kilometres, which is only 87% of the Amazon's original state.[2]

Rainforests have decreased in size primarily due to deforestation. Despite reductions in the deforestation rate over the last ten years, the Amazon rainforest will be reduced by 40% by 2030 at the current rate.[3] Between May 2000 and August 2006, Brazil lost nearly 150,000 km2 of forest, an area larger than Greece. According to the Living Planet Report 2010, deforestation continues at an alarming rate. But at the CBD 9th Conference, 67 ministers signed up to help achieve zero net deforestation by 2020.[4]

History

In the 1940s Brazil began a program of national development in the Amazon Basin. President Getúlio Vargas declared emphatically that:

The Amazon, in the impact of our will and labor, will cease to be a simple chapter in the world, and made equivalent to other great rivers, shall become a chapter in the history of human civilization. Everything which has up to now been done in Amazonas, whether in agriculture or extractive industry... must be transformed into rational exploitation.

— Getúlio Vargas[5]

Vargas established many government programs to develop his vision, including the Superintendency for the Economic Valorization of Amazonia (SPVEA) in 1953,[6] the Superintendency for the Development of Amazonia (SUDAM) in 1966, and the National Institute for Colonization and Agrarian Reform (INCRA) in 1970. In the 1960s deforestation of the Brazilian Amazon became more widespread, chiefly from forest removal for cattle ranching to raise national revenue in a period of high world beef prices, to eliminate hunger and to pay off international debt obligations.[5] Extensive transportation projects, such as the Trans-Amazon Highway, were promoted in 1970, meaning that huge areas of forest would be removed for commercial purposes.

Before the 1960s, much of the forest remained intact due to restrictions on access to the Amazon beyond partial clearing along the river banks.[7] The poor soil made plantation-based agriculture unprofitable. The key point in deforestation of the Amazon came when colonists established farms in the forest in the 1960s. They farmed based on crop cultivation and used the slash and burn method. The colonists were unable to successfully manage their fields and the crops due weed invasion and loss of soil fertility.[8] Soils in the Amazon are productive for only a very short period of time after the land is cleared, so farmers there must constantly move and clear more and more land.[8]

Amazonian colonization was dominated by cattle raising, not only because grass did grow in the poor soil, but also because ranching required little labor, generated decent profit, and awarded social status. However, farming led to extensive deforestation and environmental damage.[9]

An estimated 30% of deforestation is due to small farmers and the rate of deforestation is higher in areas they inhabit is greater than in areas occupied by medium and large ranchers, who own 89% of the Legal Amazon's private land. This underlines the importance of using previously-cleared land for agriculture, rather the more usual, politically easier, path of distributing still-forested areas.[10] The number of small farmers versus large landholders fluctuates with economic and demographic pressures.[10]

In 1964, a Brazilian land law passed that supported ownership of the land by the developer: if a person could demonstrate "effective cultivation" for a year and a day, that person could claim the land. This act paved the way for clearance of enormous areas of forest for cattle production.[11]

In the 1970s, with construction of the Trans-Amazonian Highway, INCRA established schemes to attract hundreds of thousands of potential farmers westward into the Amazon and exploit the forest for cattle ranches. Between 1966 and 1975 Amazon land values grew at a rate of 100% per year as the government offered subsidies to reform the land; throughout the 1970s and 1980s, farmers rushed to claim land and quickly convert areas to farming and make a profit due to the improved transportation network and the high price of beef.[5] The forest was also exploited for timber, which provided Brazil a way of paying off international debt.[12] By the late 1980s, an area the size of England, Scotland and Wales was being cleared annually.[13]

Causes

Cattle ranching and infrastructure

The annual rate of deforestation in the Amazon region continued to increase from 1990 to 2003 because of factors at local, national, and international levels.[7] 70% of formerly forested land in the Amazon, and 91% of land deforested since 1970, is used for livestock pasture.[14][15] The Brazilian government initially attributed 38% of all forest loss between 1966 and 1975 to large-scale cattle ranching. According to the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR), "between 1990 and 2001 the percentage of Europe's processed meat imports that came from Brazil rose from 40 to 74 percent" and by 2003 "for the first time ever, the growth in Brazilian cattle production, 80 percent of which was in the Amazon was largely export driven."[16]

Forest removal to make way for cattle ranching was the leading cause of deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon from the mid-1960s on. In addition to Vargas's earlier goal of commercial development, the devaluation of the Brazilian real against the dollar had the result of doubling the price of beef in reals and gave ranchers a widespread incentive to increase the size of their cattle ranches and areas under pasture for mass beef production, resulting in large areas of forest removal. Access to clear the forest was facilitated by the land tenure policy in Brazil that meant developers could proceed without restraint and install new cattle ranches which in turn functioned as a qualification for land ownership.[17]

Removal of the Amazon forest for cattle farming in Brazil was also seen by developers as economic investment during periods of high inflation when appreciation of cattle prices providing a way to outpace the interest rate earned on money left in the bank. Brazilian beef was more competitive on the world market at a time when extensive improvements in the road network in the Amazonas in the early 1970s through the Trans Amazonian highway and other new roads gave potential developers access to vast areas of previously-inaccessible forest. This coincided with lower transportation costs due to cheaper fuels such as ethanol, which lowered the costs of shipping the beef from the forest and gave ranchers an incentive to maximise profits.

Cattle ranching is not an environmentally friendly investment though. Cattle emit large amounts of methane. These emissions play a major role in climate change because methane's ability to trap heat is 20 times greater than that of carbon dioxide in a time horizon of 100 years and exponentially higher in shorter time horizons.[18][19] One cow can emit up to 130 gallons of methane a day, just by belching.[20]

In the 1970s, Brazil planned a massive transportation infrastructure development, a 2,000-mile (3,200 km) highway that would completely cross the Amazon forest, increasing the vulnerability of poor farmers to colonizers seeking new areas for commercial development. Studies by the Environmental Defense Fund found that areas affected by the road network were eight times more likely to be deforested by cultivators than untouched lands and that the roads allowed developers to increasingly exploit the forest reserves not only for pastoral production but also for wood exports and woodcutting for fuel and for construction. Developers were often given a six-month salary and substantial agricultural loans to remove the forest along roads in 250-acre (1.0 km2) lots for new cattle ranches.

The Brazilian government granted land to approximately 150,000 families in the Amazon between 1995 and 1998. Poor farmers were also encouraged by the government through programmes such as the National Institute for Colonization and Agrarian Reform in Brazil (INCRA) to farm unclaimed forest land and after a five-year period were given title and the right to sell the land. The productivity of the soil following forest removal for farming lasts only a year or two before the fields become infertile and farmers must clear new areas of forest to maintain their income. In 1995 nearly half, 48%, of the deforestation in Brazil was attributed to poorer farmers clearing lots under 125 acres (0.51 km2) in size.

Hydroelectric

Hydroelectric dam projects in the Amazon have also been responsible for flooding significant areas of the forest.[21] In particular the Balbina dam flooded approximately 2,400 km2 (930 sq mi) of rainforest on completion and its reservoir emitted 23,750,000 tons of carbon dioxide and 140,000 tons of methane in only its first three years of operation.[17][22] The construction of these dams encourages the construction of roads that introduce foresters, which in turn leads to deforestation.[23]

Mining activities

Mining has also increased deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon particularly since the 1980s with miners often clearing forest to open the mines, often also using them for building material, collecting wood for fuel and subsistence agriculture.

Soybean production

In addition, Brazil is currently the second-largest global producer of soybeans after the United States, mostly for livestock feed, and as prices for soybeans rise, soy farmers pushing north into forested areas of the Amazon. As stated in the Constitution of Brazil, clearing land for crops or fields is considered an ‘effective use’ of land and is a first step toward land ownership.[7] Cleared property is also valued 5–10 times more than forested land and for that reason valuable to the owner whose ultimate objective is resale. The soy industry is an important exporter for Brazil; therefore, the needs of soy farmers have been used to validate many of the controversial transportation projects that are currently developing in the Amazon.[7]

Cargill, a multinational company which controls the majority of the soya bean trade in Brazil has been criticized, along with fast food chains like McDonald's, by active groups such as Greenpeace for accelerating the process of the deforestation of the Amazon. Cargill is the main supplier of soya beans to large fast food companies such as McDonald's which uses the soya products to feed their cattle and chickens. As fast food chains expand, fast food chains must increase the quantity of their livestock in order to produce more products. In order to meet the large demands of soya, Cargill is forced to expand its soya production by clear cutting parts of the Amazon.[24]

The first two highways: the Rodovia Belém-Brasília (1958) and the Cuiabá-Porto Velho (1968), were the only federal highways in the Legal Amazon to be paved and passable year-round before the late 1990s. These two highways are said to be "at the heart of the ‘arc of deforestation’," which at present is the focal point area of deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon. The Belém-Brasília highway attracted nearly two million settlers in the first twenty years. The success of the Belém-Brasília highway in opening up the forest was re-enacted as paved roads continued to be developed unleashing the irrepressible spread of settlement. The completions of the roads were followed by a wave of resettlement and the settlers had a significant effect on the forest.[9]

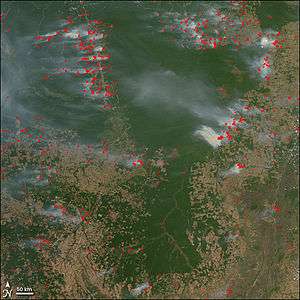

Scientists using NASA satellite data have found that clearing for mechanized cropland has recently become a significant force in Brazilian Amazon deforestation. This change in land use may alter the region's climate and the land's ability to absorb carbon dioxide. Researchers found that in 2003, the peak year of deforestation, more than 20 percent of the Mato Grosso state's forests were converted to cropland. This finding suggests that the recent cropland expansion in the region is contributing to further deforestation. In 2005, soybean prices fell by more than 25 percent and some areas of Mato Grosso showed a decrease in large deforestation events, although the central agricultural zone continued to clear forests. But, deforestation rates could return to the high levels seen in 2003 as soybean and other crop prices begin to rebound in international markets. Brazil has become a leading worldwide producer of grains including soybean, which accounts for 5% of the nation's exports.[25] This new driver of forest loss suggests that the rise and fall of prices for other crops, beef and timber may also have a significant impact on future land use in the region, according to the study.[26]

Logging

.jpg)

Logging in Brazil's Amazon is economically motivated. Although illegal logging is not, it is the most widespread problem.[27] The economic opportunity for developing regions is driven by timber export and demand for charcoal. Charcoal-producing ovens use large amounts of timber. In one month, the Brazilian government destroyed 800 illegal ovens in Tailândia. These 800 ovens were estimated to consume about 23,000 trees per month.[28] Logging for timber export is selective, since only a few species, such as mahogany, have commercial value and are harvested. Selective logging still does a lot of damage to the forest. For every tree harvested, 5-10 other trees are logged, to transport the logs through the forest. Also, a falling tree takes down a lot of other small trees. A logged forest contains significantly fewer species than areas where selective logging has not taken place. A forest disturbed by selective logging is also significantly more vulnerable to fire.[29]

Logging in the Amazon, in theory, is controlled and only strictly licensed individuals are allowed to harvest the trees in selected areas. In practice, illegal logging is widespread in Brazil.[30] Up to 60 to 80 percent of all logging in Brazil is estimated to be illegal, with 70% of the timber cut wasted in the mills.[31] Most illegal logging companies are international companies that don't replant the trees and the practice is extensive. Expensive wood such as mahogany is illegally exported to profit these companies. Fewer trees mean that less photosynthesis will occur and therefore oxygen levels drop. Carbon dioxide emissions increase, as this gas is released from a tree when it's cut down. A tree can absorb as much as 48 pounds of carbon per year so illegal logging has a major impact on climate change.[32]

To combat this destruction, the Brazilian government has stopped issuing new permits for logging. Unauthorized harvesting has continued nonetheless. Efforts to prevent cutting down forests include payments to land owners. Instead of banning logging all together, the government hopes payments of comparable sums will dissuade owners from further deforestation.[33]

Effects

One of the major concerns arising from deforestation in Brazil is the global effect it produces on climatic change. Rain forests, of vital importance in the carbon dioxide exchange process, are second only to oceans as the most important sinks on the planet for absorbing the increasing atmospheric carbon dioxide resulting from industry.

The most recent survey on deforestation and greenhouse gas emissions reports that deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon is responsible for as much as 10% of current greenhouse gas emissions due to the removal of forest which would otherwise have absorbed the emissions, and has a clear effect on global warming. The method often used to remove the forest, where many trees are burned to the ground, emits vast amounts of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, affecting air quality not just in Brazil but globally.

Fires intended to burn limited areas of forest to make way for allocated agricultural plots, frequently burn get out of control and burn much more extensive areas of land than intended. Between July and October 1987, about 19,300 square miles (50,000 km2) of rainforest was burned in the states of Pará, Mato Grosso, Rondônia, and Acre releasing more than 500 million tons of carbon, 44 million tons of carbon monoxide, and millions of tons of nitrogen oxides and other poisonous chemicals into the atmosphere.[34] In 2005 forest fires in Brazil caused widespread disruptions across the Amazon region, including airport closures and hospitalizations for smoke inhalation.

Carbon present in the trees is essential for ecosystem development and plays a key role in the regional and global climate. Fallen leaves from deforestation leave behind a mass of dead plant material known as slash, which on decomposition provides a food source for invertebrates. This had the indirect effect of increasing atmospheric carbon dioxide levels through respiration and microbial activity.[35] Simultaneously the organic carbon in the soil structure became depleted and the presence of carbon plays a vital role in the functioning of life in any ecosystem.

The Brazilian rainforest is one of the most biologically diverse regions of the world. Over a million species of plants and animals are known to live in the Amazon and many millions of species are unclassified or unknown. With rapid deforestation the habitats of many animals and plants are under threat and some species may face extinction. Deforestation reduces the gene pool; there is less of the genetic variation needed to adapt to climate change in the future. The Brazilian Amazon is known to possess vast resources for medicine and scientific research in the basin has been conducted to find a cure for major global killers such as AIDS, cancer, and other terminal diseases.

Rainforests are the oldest ecosystems on earth. Rainforest plants and animals continue to evolve, developing into the most diverse and complex ecosystems on earth. Living in limited areas, most of these species are endemic, found nowhere else in the world. In tropical rainforests, an estimated 90% of the species of the ecosystem live in the canopy. Since tropical rainforests are estimated to hold 50% of the planet's species, the canopy of rainforests worldwide may hold 45% of life on Earth. The Amazon rainforest borders 8 countries, and has the world's largest river basin and is the source of 1/5 of the Earth's river water. It has the world's greatest diversity of birds and freshwater fish. The Amazon is home to more species of plants and animals than any other terrestrial ecosystem on the planet—perhaps 30% of the world's species are found there.

More than 300 species of mammals are found in the Amazon, the majority bats and rodents. The Amazon basin contains more freshwater fish species than anywhere else in the world—more than 3,000 species. More than 1500 bird species are also found there. Frogs are overwhelmingly the most abundant amphibians in the rainforest. Interdependence, when species depend on one another, takes many forms in the forest, from species relying on other species for pollination and seed dispersal to predator-prey relationships to symbiotic relationships. Each species that disappears from the ecosystem may weaken the survival chances of another, while the loss of a keystone species—an organism that links many other species together—could cause a significant disruption in the functioning of the entire system.

.jpg)

Forest removal affects the social and economic lives of the indigenous people who live in the forests and whose families have lived there in relative isolation for many centuries. These indigenous peoples, like the Kayapo, have an intimate understanding of the ecology of the Amazon.[36] The subsequent loss of these people may also prove to be a loss of knowledge. The rainforest is their home, and a fundamental source of food, shelter, fuel, nourishment cultural heritage and recreation. Deforestation for the export of timber removes valuable protection for the soils in a dynamic ecosystem and regions prone to desertification and silting of river banks as rivers become clogged with eroded soils in sparse areas. If too much timber is cut, soil that once had sufficient cover can get baked and dry out in the sun, leading to erosion and degradation of soil fertility and farmers cannot profit from their land even after clearing it. According to the United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP) in 1977, deforestation is a major cause of desertification and in 1980 threatened 35% of the world's land surface and 20% of the world's population.[37]

Exploitation of forests for mining activities such as gold mining has also significantly increased the risk of mercury poisoning and contamination of the ecosystem and water.[38] Mercury poisoning can affect the food chain and affect wildlife both on land and in the rivers. It can also affect plants and the crops of farmers trying to farm forest areas. Pollution may result from mine sludge and affect the functioning of the river system when exposed soil is blown in the wind and can have a significant impact on aquatic populations further affected by dam building in the region. Dams may have a profound impact on migrating fish and ecological life and leave plains prone to flooding and leaching.

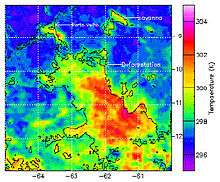

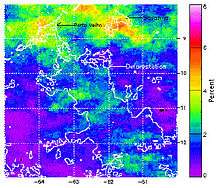

NASA survey

In the American Meteorological Society Journal of Climate, two research meteorologists at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center Andrew Negri and Robert Adler have analysed the impact of deforestation on climatic patterns in the Amazon using data and observatory readings collected from NASA's Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission over many years. Working also with the University of Arizona and the North Carolina State University Negri said "In deforested areas, the land heats up faster and reaches a higher temperature, leading to localized upward motions that enhance the formation of clouds and ultimately produce more rainfall".[39]

They also examined cloud cover in deforested areas. In comparison with areas still unaffected by deforestation they found a significant increase in cloud cover and rainfall during the August–September wet season where forest had been cleared. The height or existence of plants and trees in the forest directly affects the aerodynamics of the atmosphere, and precipitation in the area. In addition the Massachusetts Institute of Technology developed a series of detailed computer simulation models of rainfall patterns in the Amazon during the 1990s and concluded that forest removal also leaves soil exposed to the sun, and the increased temperature on the surface enhances evaporation and increases moisture in the air.

Measured rates

Deforestation rates in the Brazilian Amazon have slowed dramatically since peaking in 2004 at 27,423 square kilometers per year. By 2009, deforestation had fallen to around 7,000 square kilometers per year, a decline of nearly 75 percent from 2004, according to Brazil's National Institute for Space Research (Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas Espaciais, or INPE),[40] which produces deforestation figures annually.

Their deforestation estimates are derived from 100 to 220 images taken during the dry season in the Amazon by the China–Brazil Earth Resources Satellite program (CBERS), and may only consider the loss of the Amazon rainforest – not the loss of natural fields or savanna within the Amazon biome. According to INPE, the original Amazon rainforest biome in Brazil of 4,100,000 km2 was reduced to 3,403,000 km2 by 2005 – representing a loss of 17.1%.[40]

According to estimates based on data from the National Institute for Space Research and the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO),[41] the rates of deforestation in Amazon Rainforest are:

| Period | Estimated remaining forest cover in the Brazilian Amazon (km2) | Annual forest loss (km2) | Percent of 1970 cover remaining | Total forest loss since 1970 (km2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre–1970 | 4,100,000 | — | — | — |

| 1977 | 3,955,870 | 21,130 | 96.5% | 144,130 |

| 1978–1987 | 3,744,570 | 21,130 | 91.3% | 355,430 |

| 1988 | 3,723,520 | 21,050 | 90.8% | 376,480 |

| 1989 | 3,705,750 | 17,770 | 90.4% | 394,250 |

| 1990 | 3,692,020 | 13,730 | 90.0% | 407,980 |

| 1991 | 3,680,990 | 11,030 | 89.8% | 419,010 |

| 1992 | 3,667,204 | 13,786 | 89.4% | 432,796 |

| 1993 | 3,652,308 | 14,896 | 89.1% | 447,692 |

| 1994 | 3,637,412 | 14,896 | 88.7% | 462,588 |

| 1995 | 3,608,353 | 29,059 | 88.0% | 491,647 |

| 1996 | 3,590,192 | 18,161 | 87.6% | 509,808 |

| 1997 | 3,576,965 | 13,227 | 87.2% | 523,035 |

| 1998 | 3,559,582 | 17,383 | 86.8% | 540,418 |

| 1999 | 3,542,323 | 17,259 | 86.4% | 557,677 |

| 2000 | 3,524,097 | 18,226 | 86.0% | 575,903 |

| 2001 | 3,505,932 | 18,165 | 85.5% | 594,068 |

| 2002 | 3,484,538 | 21,651 | 85.0% | 615,719 |

| 2003 | 3,459,291 | 25,396 | 84.4% | 641,115 |

| 2004 | 3,431,868 | 27,772 | 83.7% | 668,887 |

| 2005 | 3,412,022 | 19,014 | 83.2% | 687,901 |

| 2006 | 3,397,913 | 14,285 | 82.9% | 702,186 |

| 2007 | 3,386,381 | 11,651 | 82.6% | 713,837 |

| 2008 | 3,375,413 | 12,911 | 82.3% | 726,748 |

| 2009 | 3,365,788 | 7,464 | 82.1% | 734,212 |

| 2010 | 3,358,788 | 7,000 | 81.9% | 741,212 |

| 2011 | 3,352,370 | 6,418 | 81.8% | 747,630 |

| 2012 | 3,347,799 | 4,571 | 81.7% | 752,201 |

| 2013 | 3,341,908 | 5,891 | 81.5% | 758,092 |

| 2014 | 3,336,896 | 5,012 | 81.4% | 763,104 |

| 2015 | 3,331,065 | 5,831 | 81.2% | 768,935 |

Response

By the end of the 1980s, the removal of Brazil's forests had become a serious global issue, not only because of the loss of biodiversity and ecological disruption, but also because of the large amounts of carbon dioxide (CO2) released from burned forests and the loss of a valuable sink to absorb global CO2 emissions. At the 1992 UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, deforestation became a key issue addressed at the summit in Rio de Janeiro. Plans for the compensated reduction (CR) of greenhouse gas emissions from tropical forests were set up to give nations like Brazil an incentive to curb their rate of deforestation.

"We are encouraging the Brazilian government to fully endorse the Compensated Reduction proposal", said scientist Paulo Moutinho, coordinator of the climate change program of the Amazon Institute for Environmental Research (IPAM), an NGO research institute in Brazil.[43] In Brazil, the cost of reducing deforestation emissions by half will be less than $5 per ton of carbon dioxide, estimated an unpublished study of IPAM and the Woods Hole Research Center.

On May 11, 1994, two scientists, Compton Tucker and David Skole, presented the results of a NASA survey at the Subcommittee on Western Hemisphere Affairs of the United States Congress, a formal scientific assessment of deforestation in Brazil and the rate of forest removal as well as questions on the effectiveness of Brazilian environmental policies. Whilst undertaking a monitoring and complete assessment was very difficult due to the size of the rainforest, they concluded that satellite observations showed a reduction in the rate of forest removal between 1992 and 1993 and that World Bank estimates of 600,000 square km2 (12%) cleared to that point appeared to be too high. The NASA assessment concurred with the findings of the Brazilian National Space Research Institute (INPE) an estimated 280,000 km2 (5%) in the same period.[44]

The following year (1995) deforestation nearly doubled; this has been attributed the accidental fire following El Niño-related drought rather than active logging and the following year again showed a major drop.[45] In 2002 Brazil ratified the Kyoto Agreement as a developing nation listed in the non-Annex I countries. These countries do not have carbon emission quotas in the agreement as developed nations do.[46] President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva reiterated that Brazil "is in charge of looking after the Amazon."[47]

In 2006 Brazil proposed a direct finance project to deal with the Reduced Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation in Developing Countries, or REDD, issue, recognizing that deforestation contributes to 20% of the world's greenhouse gas emissions. The competing proposal for the REDD issue was a carbon emission credit system, where reduced deforestation would receive "marketable emissions credits". In effect, developed countries could reduce their carbon emissions, and approach their emissions quota by investing in the reforestation of developing rainforest countries. Instead, Brazil's 2006 proposal would draw from a fund based on donor country contributors.[47]

By 2005 forest removal had fallen to 9,000 km2 (3,500 sq mi) of forest compared to 18,000 km2 (6,900 sq mi) in 2003[48] and on July 5, 2007, Brazilian president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva announced at the International Conference on Biofuels in Brussels that more than 20 million hectares of conservation units to protect the forest and more efficient fuel production had allowed the rate of deforestation to fall by 52% in the three years since 2004.[49]

Daniel Nepstad of the Woods Hole Research Center has demonstrated that Brazil's deforestation rates have been cut nearly in half in recent years through a combination of government intervention and economic trends. Since 2004 the country has established more than 200,000 km2 of parks, nature reserves, and national forests in the Amazon rainforest. These protected areas, if fully enforced, would keep an estimated one billion tons of carbon going into the atmosphere through deforestation by the year 2015.[50] The academic evidence suggests that the creation of public lands, through the assignment of property rights, reduces incentives to deforest land for agricultural conversion and contributes to lower land-related conflict.[51]

In 2005 Brazilian Environment Minister Marina da Silva announced that 9,000 km2 (3,500 sq mi) of forest had been felled in the previous year, compared with more than 18,000 km2 (6,900 sq mi) in 2003 and 2004.[48] Between 2005 and 2006 there was a 41% drop in deforestation; nonetheless, Brazil still had the largest area of forest removed annually on the planet.[1]

These methods have also reduced the illegal appropriation of land and logging, encouraging the use of land for sustainable timber harvesting.

Future

The improvement of the social and economic conditions of the huge population of poor people in Brazil is the main concern of the government.

It is clear that to diminish deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon would require enormous financial resources to compensate the loggers and given them an economic incentive to pursue other areas of activity. The World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) has estimated that a total of approximately US$547.2 million (1 billion Brazilian reais) per year would be required from international sources to compensate the forest developers and establish a highly organized framework to fully implement forest governance and monitoring,[52] and the foundation of new protected forest areas in the Amazon for future sustainability.[53] Compensating the loggers over the entirety of the Amazon rainforest would require a heavy amount of funding and increased interaction with the international community, and a reform of the world market system if deforestation in the country is to be halted.

Non-governmental organizations such as WWF have been highly active in the region and WWF Brazil has formed an alliance with some eight other Brazilian NGO'S which aim to completely halt deforestation in the Amazon by 2015. Another group that have been effective is Greenpeace, an organization whose goal is to fight to save the plant from the destruction of forests, the threat of global warming and the deterioration of the ocean.[31] Other groups such as The Nature Conservancy, the proposal, known as the "Agreement on Acknowledging the Value of the Forest and Ending Amazon Deforestation," aims at combining strong public policies with market strategies to achieve annual deforestation reduction targets.[52]

The groups aim to establish a wide-ranging commitment between the sectors of the government and society to conserve the rainforest and are aiming for an overall reduction in deforestation of 68,737.8 square kilometres in seven years. Denise Hamú, the CEO of WWF-Brazil has said' "Only through the mobilization of state and federal governments, the private sector and environmental NGOs we can reach significant results for the conservation and promotion of sustainable development in the Amazon".[53]

See also

References

- 1 2 "World deforestation rates and forest cover statistics, 2000-2005". news.mongabay.com. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- ↑ Malhi, Y.; J. Timmons Roberts; Richard A. Betts; Timothy J. Killeen; Wenhong Li; Carlos A. Nobre (2009). "Climate Change, Deforestation, and the Fate of the Amazon". Science. 319 (5860): 169–172. doi:10.1126/science.1146961. PMID 18048654.

- ↑ National Geographic. January 2007.

- ↑ "Living Planet Report 2010". 2010. Retrieved 23 September 2013.

- 1 2 3 Hall, A.L. (1989) Developing Amazonia, Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- ↑ João S. Campari, 2005 The Economics of Deforestation in the Amazon.

- 1 2 3 4 Kirby, K. R., Laurance, W. F., Albernaz, A. K., Schroth, G., Fearnside, P. M., Bergen, S., Venticinque, E. M., & De Costa, C. (2006). "The future of deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon". Futures. 38 (38): 432–453. doi:10.1016/j.futures.2005.07.011. ISSN 0016-3287.

- 1 2 Watkins and Griffiths, J. (2000). Forest Destruction and Sustainable Agriculture in the Brazilian Amazon: a Literature Review (Doctoral dissertation, The University of Reading, 2000). Dissertation Abstracts International, 15-17

- 1 2 Williams, M. (2006). Deforesting the Earth: From Prehistory to Global Crisis. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

- 1 2 Fernside, P. M. (2005). Deforestation in Brazilian Amazonia: History, Rates, and Consequences. Conservation Biology, 19, 680-688.

- ↑ "Brazil Deforestation: Latifundios and Landless". Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- ↑ Andrew Buncombe (2005-03-29). "Brazil: Battle for the Heart of the Forest". The Independent UK. Archived from the original on 2006-11-21. Retrieved 2007-12-10.

- ↑ "Speeches and Articles - Prince of Wales". www.princeofwales.gov.uk. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- ↑ H. Steinfeld, P. Gerber, T. Wassenaar, V. Castel, M. Rosales, C. de Haan. Livestock's Long Shadow: Environmental Issues and Options. United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization. 2006. Archived 2014-08-06 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Sergio Marglis. "Causes of Deforestation of the Brazilian Amazon." World Bank Working Paper No. 22. The World Bank. 2004.

- ↑ Center for International Forestry Research (2007-10-27). "Beef exports fuel loss of Amazonian Forest". Center for International Forestry Research. Archived from the original on 2007-12-09. Retrieved 2007-11-27.

- 1 2 "Deforestation in the Amazon." mongabay.com.

- ↑ "IPCC Fourth Assessment Report: Climate Change 2007; Climate Change 2007: Working Group I: The Physical Science Basis; 2.10.2 Direct Global Warming Potentials". Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Retrieved September 12, 2016.

- ↑ Shindell, D. T.; Faluvegi, G.; Koch, D. M.; Schmidt, G. A.; Unger, N.; Bauer, S. E. (2009), "Improved attribution of climate forcing to emissions", Science (in German) (Science 326 ed.), AAAS, 326 (5953): 716–718, doi:10.1126/science.1174760, PMID 19900930 Online

- ↑ "A Warming World Pollution on the Hoof". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 19 April 2011.

- ↑ "MSNBC.com". Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- ↑ Downie, Andrew (2010-04-22). "In Earth Day setback, Brazil OKs dam that will flood swath of Amazon". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 2011-12-06.

- ↑ "Amazon Dams Keep the Lights On But Could Hurt Fish, Forests". 19 April 2015. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- ↑ Greenpeace. 2006. We're trashin' it: how McDonald's is eating up the Amazon. Amsterdam: Greenpeace.

- ↑ Simoes, Alexander. "The Observatory of Economic Complexity - What does Brazil Export". MIT. Archived from the original on 4 February 2014. Retrieved 22 January 2014.

- ↑ Bettwy, Mike (19 September 2006). "Growth in Amazon Cropland May Impact Climate and Deforestation Patterns". Greenbelt, Maryland: NASA. Retrieved 27 October 2015. Also available from NASA Earth Observatory News.

- ↑ "Brazil | Illegal Logging Portal". www.illegal-logging.info. Retrieved 2016-05-17.

- ↑ Reel, Monte. "Brazil Crackdown on Loggers After Surge in Cutting." Washington Post. 21 March 2008.

- ↑ "Search - The Encyclopedia of Earth". eoearth.org. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- ↑ "Amazon Destruction". Mongabay.com. Retrieved 2016-05-17.

- 1 2 "Amazon Rainforest". Greenpeace USA. Retrieved 2016-05-17.

- ↑ "Untitled Document". projects.ncsu.edu. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- ↑ Lynch, Patrick. "Concept: Paying People to Not Cut Down Trees." Daily Press, Newport News, VA. 6 Jan. 2008: A1.

- ↑ "Fires in the Rainforest." Mongabay.com.

- ↑ Jason Wolfe, Earth Observatory (2003-01-21). "The Road to Recovery". NASA Earth Observatory. Archived from the original on 2008-05-11. Retrieved 2007-12-03.

- ↑ http://web.nateko.lu.se/courses/ngen03/posey-1985.pdf

- ↑ "熟女の貴女に恋してる - 君に癒されて". www.effects-of-deforestation.com. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- ↑ "Mercury poisoning disease re-emerges". BBC News. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- 1 2 NASA, Goddard Space Flight Center (June 9, 2004). "NASA data shows deforestation affects climate in the Amazon". Retrieved 2007-12-09.

- 1 2 National Institute for Space Research (INPE) (2010)

- ↑ "Calculating Deforestation in the Amazon". Mongabay.com. Retrieved 2016-03-08.

- ↑ ""VASCONCELOS, Vitor Vieira. Map of Deforestation in Brazil for each Biome: 2002 to 2008. Ministério Público de Minas Gerais. Coordenadoria Geral de Promotorias por Bacias Hidrográficas. 2012"". Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- ↑ Science Daily. Published May 16, 2007. Retrieved November 27, 2007.

- ↑ Deforestation - Facts

- ↑ "Features". earthobservatory.nasa.gov. 15 April 2018. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- ↑ "Brazilian Senate Ratifies Kyoto Protocol." UN Wire: Email News Covering the United Nations and the World. 24 Jan 2009.

- 1 2 "Brazil will forge its own path for developing the Amazon." Conservation news and environmental science news. 26 Jan 2009.

- 1 2 Tony Gibb, BBC News (2006-08-26). "Deforestation of Amazon halved". BBC.co.uk. Retrieved 2007-11-27.

- ↑ Embassy of Brazil in London (2007-07-05). "President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva - International Conference on Biofuels". Brazil.org. Archived from the original on 2010-06-04. Retrieved 2009-12-14.

- ↑ Woods Hole Research Center (2007, May 16). "Brazil Demonstrating That Reducing Tropical Deforestation Is Key Win-win Global Warming Solution."

- ↑ Thiemo Fetzer; Samuel Marden (2016-04-12). "Take what you can: property rights, contestability and conflict" (PDF). Economic Journal. Retrieved 2016-06-14.

- 1 2 http://www.worldchanging.com/archives/007413.html

- 1 2 World Wide Fund for Nature. October 4 2007.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Deforestation. |

.svg.png)