Debian

| |

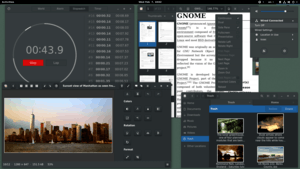

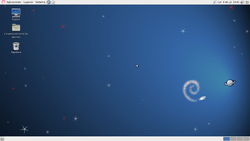

Debian 9 with GNOME v3.22 | |

| Developer | The Debian Project (Software in the Public Interest) |

|---|---|

| OS family | Unix-like |

| Working state | Current |

| Source model | Open-source |

| Initial release | September 1993 |

| Latest release | 9.5 (Stretch) (July 14, 2018[1]) [±] |

| Available in | 75 languages |

| Update method | Long-term support |

| Package manager | APT (command line and graphical front-ends), dpkg (low-level system) |

| Platforms | amd64, ia64, i386, arm64, armel, armhf, mipsel, ppc64, s390x, z/Architecture;[2] RISC-V (in progress)[3] |

| Kernel type | |

| Userland | GNU |

| Default user interface | |

| License | DFSG and compatible licenses |

| Official website |

www |

Debian (/ˈdɛbiən/)[5][6] is a Unix-like operating system composed entirely of free software packaged by a team of volunteers. The Debian Project was started by Ian Murdock on August 16, 1993, Debian 0.01 was released on September 15, 1993,[7] and the first stable version, 1.1, was released on June 17, 1996.[8] The Debian stable branch is the most popular edition for personal computers and network servers, and is used as a base for many other distributions.

The project's work is carried out over the Internet, guided by the Debian Project Leader and three foundational documents: the Debian Social Contract, the Debian Constitution, and the Debian Free Software Guidelines. New distributions are updated continually, and the next candidate is released after a time-based freeze.

One of the earliest operating systems based on the Linux kernel, Debian has been developed openly and distributed freely in the spirit of the GNU Project. This decision drew the support of the Free Software Foundation, which sponsored the project for one year from November 1994 to November 1995.[9] When the sponsorship ended, the Debian Project formed Software in the Public Interest to continue supporting development.

While all Debian releases are based on the GNU userland and GNU C Library (glibc), kernels other than Linux are also available, including FreeBSD and the GNU Hurd microkernel.

Features

Debian has access to online repositories that contain over 51,000 packages[10] making it the largest collection of software in the world.[11] Debian officially contains only free software, but non-free software can be downloaded and installed from the Debian repositories.[12] Debian includes popular free programs such as LibreOffice,[13] Firefox web browser, Evolution mail, K3b disc burner, VLC media player, GIMP image editor, and Evince document viewer.[12] Debian is a popular choice for servers, for example as the operating system component of a LAMP stack.[14][15]

Kernels

Debian supports Linux officially, having offered kFreeBSD for version 7 but not 8,[16] and GNU Hurd unofficially.[17] GNU/kFreeBSD was released as a technology preview for IA-32 and x86-64 architectures,[16] and lacked the amount of software available in Debian's Linux distribution.[18] Official support for kFreeBSD was removed for version 8, which did not provide a kFreeBSD-based distribution.

Several flavors of the Linux kernel exist for each port. For example, the i386 port has flavors for IA-32 PCs supporting Physical Address Extension and real-time computing, for older PCs, and for x86-64 PCs.[19] The Linux kernel does not officially contain firmware without sources, although such firmware is available in non-free packages and alternative installation media.[20][21]

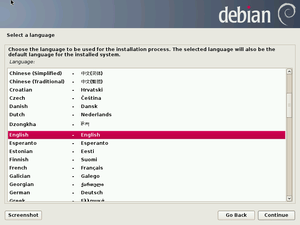

Installation and live images

Debian offers DVD and CD images for installation that can be downloaded using BitTorrent or jigdo. Physical disks can also be bought from retailers.[22] The full sets are made up of several discs (the amd64 port consists of 13 DVDs or 84 CDs),[23] but only the first disc is required for installation, as the installer can retrieve software not contained in the first disc image from online repositories.[24]

Debian offers different network installation methods. A minimal install of Debian is available via the netinst CD, whereby Debian is installed with just a base and later added software can be downloaded from the Internet. Another option is to boot the installer from the network.[25]

Installation images are hybrid on some architectures and can be used to create a bootable USB drive (Live USB).[26]

The default bootstrap loader is GNU GRUB version 2, though the package name is simply grub, while version 1 was renamed to grub-legacy. This conflicts with e.g. Fedora, where grub version 2 is named grub2.

The default desktop may be chosen from the DVD boot menu among GNOME, KDE Software Compilation, Xfce and LXDE, and from special disc 1 CDs.[27][28]

History

Founding (1993–98)

Debian was first announced on August 16, 1993, by Ian Murdock, who initially called the system "the Debian Linux Release".[29][30] The word "Debian" was formed as a portmanteau of the first name of his then-girlfriend Debra Lynn and his own first name.[31] Before Debian's release, the Softlanding Linux System (SLS) had been a popular Linux distribution and the basis for Slackware.[32] The perceived poor maintenance and prevalence of bugs in SLS motivated Murdock to launch a new distribution.[33]

Debian 0.01, released on September 15, 1993, was the first of several internal releases.[7] Version 0.90 was the first public release,[7] providing support through mailing lists hosted at Pixar.[34] The release included the Debian Linux Manifesto, outlining Murdock's view for the new operating system. In it he called for the creation of a distribution to be maintained openly, in the spirit of Linux and GNU.[35]

The Debian project released the 0.9x versions in 1994 and 1995.[36] During this time it was sponsored by the Free Software Foundation for one year.[37] Ian Murdock delegated the base system, the core packages of Debian, to Bruce Perens and Murdock focused on the management of the growing project.[38] The first ports to non-IA-32 architectures began in 1995, and Debian 1.1 was released in 1996.[39] By that time and thanks to Ian Jackson, the dpkg package manager was already an essential part of Debian.[40]

In 1996, Bruce Perens assumed the project leadership. Perens was a controversial leader, regarded as authoritarian and strongly attached to Debian.[41] He drafted a social contract and edited suggestions from a month-long discussion into the Debian Social Contract and the Debian Free Software Guidelines.[42] After the FSF withdrew their sponsorship in the midst of the free software vs. open source debate,[43] Perens initiated the creation of the legal umbrella organization Software in the Public Interest instead of seeking renewed involvement with the FSF.[39] He led the conversion of the project from a.out to ELF.[44] He created the BusyBox program to make it possible to run a Debian installer on a single floppy, and wrote a new installer.[45] By the time Debian 1.2 was released, the project had grown to nearly two hundred volunteers.[44] Perens left the project in 1998.[46]

Ian Jackson became the leader in 1998.[47] Debian 2.0 introduced the second official port, m68k.[36] During this time the first port to a non-Linux kernel, Debian GNU/Hurd, was started.[48] On December 2, the first Debian Constitution was ratified.[49]

Leader election (1999–2005)

From 1999, the project leader was elected yearly.[50] The Advanced Packaging Tool was deployed with Debian 2.1.[36] The amount of applicants was overwhelming and the project established the new member process.[51][52] The first Debian derivatives, namely Libranet,[53] Corel Linux and Stormix's Storm Linux, were started in 1999.[39] The 2.2 release in 2000 was dedicated to Joel Klecker, a developer who died of Duchenne muscular dystrophy.[54]

In late 2000, the project reorganized the archive with new package "pools" and created the Testing distribution, made up of packages considered stable, to reduce the freeze for the next release.[39] In the same year, developers began holding an annual conference called DebConf with talks and workshops for developers and technical users.[55] In May 2001, Hewlett-Packard announced plans to base its Linux development on Debian.[56]

In July 2002, the project released version 3.0, code-named Woody, the first release to include cryptographic software, a free licensed KDE and internationalization.[57] During these last release cycles, the Debian project drew considerable criticism from the free software community because of the long time between stable releases.[58][59][60]

Some events disturbed the project while working on Sarge, as Debian servers were attacked by fire and hackers.[39][61] One of the most memorable was the Vancouver prospectus.[62][63][64] After a meeting held in Vancouver, release manager Steve Langasek announced a plan to reduce the number of supported ports to four in order to shorten future release cycles.[65] There was a large reaction because the proposal looked more like a decision and because such a drop would damage Debian's aim to be "the universal operating system".[66][67][68]

Sarge and later releases (2005–present)

The 3.1 Sarge release was made in June 2005. This release updated 73% of the software and included over 9,000 new packages. A new installer with a modular design, Debian-Installer, allowed installations with RAID, XFS and LVM support, improved hardware detection, made installations easier for novice users, and was translated into almost forty languages. An installation manual and release notes were in ten and fifteen languages respectively. The efforts of Skolelinux, Debian-Med and Debian-Accessibility raised the number of packages that were educational, had a medical affiliation, and ones made for people with disabilities.[39][69]

In 2006, as a result of a much-publicized dispute, Mozilla software was rebranded in Debian, with Firefox forked as Iceweasel and Thunderbird as Icedove. The Mozilla Corporation stated that software with unapproved modifications could not be distributed under the Firefox trademark. Two reasons that Debian modifies the Firefox software are to change the non-free artwork and to provide security patches.[70][71] In February 2016, it was announced that Mozilla and Debian had reached an agreement and Iceweasel would revert to the name Firefox; similar agreement was anticipated for Icedove/Thunderbird.[72]

A fund-raising experiment, Dunc-Tank, was created to solve the release cycle problem and release managers were paid to work full-time;[73] in response, unpaid developers slowed down their work and the release was delayed.[74] Debian 4.0 (Etch) was released in April 2007, featuring the x86-64 port and a graphical installer.[36] Debian 5.0 (Lenny) was released in February 2009, supporting Marvell's Orion platform and netbooks such as the Asus Eee PC.[75] The release was dedicated to Thiemo Seufer, a developer who died in a car crash.[76]

In July 2009, the policy of time-based development freezes on a two-year cycle was announced. Time-based freezes are intended to blend the predictability of time based releases with Debian's policy of feature based releases, and to reduce overall freeze time.[77] The Squeeze cycle was going to be especially short; however, this initial schedule was abandoned.[78] In September 2010, the backports service became official, providing more recent versions of some software for the stable release.[79]

Debian 6.0 (Squeeze) was released in February 2011, introduced Debian GNU/kFreeBSD as a technology preview, featured a dependency-based boot system, and moved problematic firmware to the non-free area.[80] Debian 7.0 (Wheezy) was released in May 2013, featuring multiarch support[81] and Debian 8.0 (Jessie) was released in April 2015, using systemd as the new init system.[82] Debian 9.0 (Stretch) was released in June 2017.[83][84] At present, Debian is still in development and new packages are uploaded to unstable every day.[85]

Throughout Debian's lifetime, both the Debian distribution and its website have won various awards from different organizations,[86] including Server Distribution of the Year 2011,[87] The best Linux distro of 2011,[88] and a Best of the Net award for October 1998.[89]

On December 2, 2015, Microsoft announced that they would offer Debian GNU/Linux as an endorsed distribution on the Azure cloud platform.[90][91]

Releases

Release cycle

Stable version of Debian gets released approximately every 2 years. It will receive official support for about 3 years with update for major security or usability fixes. Point releases will be available every several months as determined by Stable Release Managers (SRM).[92]

Debian also launched its Long Term Support (LTS) project since Debian 6 (Debian Squeeze). For each Debian release, it will receive two years of extra security updates provided by LTS Team after its End Of Life (EOL). However, no point releases will be made. Now each Debian release can receive 5 years of security support in total.[93]

Desktop environments

Debian offers CD images specifically built for Xfce, the default desktop on CD, and DVD images for GNOME, KDE and others.[80] MATE is officially supported,[94] while Cinnamon support was added with Debian 8.0 Jessie.[95] Less common window managers such as Enlightenment, Openbox, Fluxbox, IceWM, Window Maker and others are available.[96]

The default desktop environment of version 7.0 Wheezy was temporarily switched to Xfce, because GNOME 3 did not fit on the first CD of the set.[97] The default for the version 8.0 Jessie was changed again to Xfce in November 2013,[98] and back to GNOME in September 2014.[99]

Debian Live

Debian releases live install images for CDs, DVDs and USB thumb drives, for IA-32 and x86-64 architectures, and with a choice of desktop environments. These Debian Live images allow users to boot from removable media and run Debian without affecting the contents of their computer.

A full install of Debian to the computer's hard drive can be initiated from the live image environment.[100]

Personalized images can be built with the live-build tool for discs, USB drives and for network booting purposes.[101]

Package management

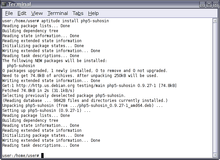

Package management operations can be performed with different tools available on Debian, from the lowest level command dpkg to graphical front-ends like Synaptic. The recommended standard for administering packages on a Debian system is the apt toolset.[102]

dpkg provides the low-level infrastructure for package management.[103] The dpkg database contains the list of installed software on the current system. The dpkg command tool does not know about repositories. The command can work with local .deb package files, and information from the dpkg database.[104]

APT tools

An Advanced Packaging Tool (APT) tool allows administering an installed Debian system to retrieve and resolve package dependencies from repositories. APT tools share dependency information and cached packages.[102]

- Aptitude is a command line tool that also offers a text-based user interface. The program comes with enhancements such as better search on package metadata.[102]

- apt-get and apt-cache are command tools of the standard apt package. apt-get installs and removes packages, and apt-cache is used for searching packages and displaying package information.[102]

GDebi and other front-ends

GDebi is an APT tool which can be used in command-line and on the GUI.[105] GDebi can install a local .deb file via the command line like the dpkg command, but with access to repositories to resolve dependencies.[106] Other graphical front-ends for APT include Software Center,[107] Synaptic[108] and Apper.[109]

GNOME Software is a graphical front-end for PackageKit, which itself can work on top of various software packaging systems.

Branches

Three branches of Debian (also called releases, distributions or suites) are regularly maintained:[110]

- Stable is the current release and targets stable and well-tested software needs.[111] Stable is made by freezing Testing for a few months where bugs are fixed and packages with too many bugs are removed; then the resulting system is released as stable. It is updated only if major security or usability fixes are incorporated.[112] This branch has an optional backports service that provides more recent versions of some software.[79] Stable's CDs and DVDs can be found in the Debian website.[23]

- Testing is the preview branch that will eventually become the next major release. The packages included in this branch have had some testing in unstable but they may not be fit for release yet. It contains newer packages than stable but older than unstable. This branch is updated continually until it is frozen.[112] Testing's CDs and DVDs can be found on the Debian website.[23]

- Unstable, always codenamed sid, is the trunk. Packages are accepted without checking the distribution as a whole.[112] This branch is usually run by software developers who participate in a project and need the latest libraries available, and by those who prefer bleeding-edge software.[110] Debian does not provide full Sid installation discs, but rather a minimal ISO that can be used to install over a network connection. Additionally, this branch can be installed through a system upgrade from stable or testing.[113]

Other branches in Debian:

- Oldstable is the prior stable release.[112] It is supported by the Debian Security Team until one year after a new stable is released, and since the release of Debian 6, for another 2 years through the Long Term Support project.[114] Eventually, oldstable is moved to a repository for archived releases.[112]

- Oldoldstable is the prior oldstable release. It is supported by the Long Term Support community. Eventually, oldoldstable is moved to a repository for archived releases.

- Experimental is a temporary staging area of highly experimental software that is likely to break the system. It is not a full distribution and missing dependencies are commonly found in unstable, where new software without the damage chance is normally uploaded.[112]

The snapshot archive provides older versions of the branches. They may be used to install a specific older version of some software.[115]

Numbering scheme

Stable and oldstable get minor updates, called point releases; as of July 2018, the stable release is version 9.5,[116] and the oldstable release is version 8.10.[117]

The numbering scheme for the point releases up to Debian 4.0 was to include the letter r (for revision)[118] after the main version number and then the number of the point release; for example, the latest point release of version 4.0 is 4.0r9.[119] This scheme was chosen because a new dotted version would make the old one look obsolete and vendors would have trouble selling their CDs.[120]

From Debian 5.0, the numbering scheme of point releases was changed, conforming to the GNU version numbering standard;[121] the first point release of Debian 5.0 was 5.0.1 instead of 5.0r1.[122] The numbering scheme was once again changed for the first Debian 7 update, which was version 7.1.[123] The r scheme is no longer in use, but point release announcements include a note about not throwing away old CDs.[124]

Code names

The code names of Debian releases are names of characters from the Toy Story films.

The testing suite is currently named Buster,[125] which is the real (not the toy) dog seen in Toy Story 2 and Toy Story 3.

The unstable suite is permanently nicknamed Sid, after the emotionally unstable boy next door who regularly destroyed toys.[126]

Debian 8, the current oldstable, was named Jessie after the cowgirl in Toy Story 2 and Toy Story 3.

Debian 9, the current stable, was named Stretch after the toy rubber octopus in Toy Story 3.

Debian 10 freeze is planned for March 2019, and the release will be "some time mid 2019". It will be called Buster.

Debian 11 will be called Bullseye,[127] after Woody's toy horse.

Debian 12 will be called Bookworm,[128] after the intelligent worm toy with a built-in flash-light seen in Toy Story 3.

This naming tradition came about because Bruce Perens was involved in the early development of Debian while working at Pixar.[41]

Blends

Debian Pure Blends are subsets of a Debian release configured out-of-the-box for users with particular skills and interests.[129] For example, Debian Jr. is made for children, while Debian Science is for researchers and scientists.[130] The complete Debian distribution includes all available Debian Pure Blends.[129] "Debian Blend" (without "Pure") is a term for a Debian-based distribution that strives to become part of mainstream Debian, and have its extra features included in future releases.[131]

Logo

The Debian "swirl" logo was designed by Raul Silva[132][133] in 1999 as part of a contest to replace the semi-official logo that had been used.[134] The winner of the contest received an @debian.org email address, and a set of Debian 2.1 install CDs for the architecture of their choice. There has been no official statement from the Debian project on the logo's meaning, but at the time of the logo's selection, it was suggested that the logo represented the magic smoke ( or the genie ) that made computers work.[135][136][137]

One theory about the origin of the Debian logo is that Buzz Lightyear, the chosen character for the first named Debian release, has a swirl in his chin.[138][139] Stefano Zacchiroli also suggested that this swirl is the Debian one.[140]

Archive areas

The Debian Free Software Guidelines (DFSG) define the distinctive meaning of the word "free" as in "free and open-source software".[141] Packages that comply with these guidelines, usually under the GNU General Public License, Modified BSD License or Artistic License,[142] are included inside the main area;[112] otherwise, they are included inside the non-free and contrib areas. These last two areas are not distributed within the official installation media, but they can be adopted manually.[141]

Non-free includes packages that do not comply with the DFSG,[143] such as documentation with invariant sections and proprietary software,[144][145] and legally questionable packages.[143] Contrib includes packages which do comply with the DFSG but fail other requirements. For example, they may depend on packages which are in non-free or requires such for building them.[143]

Richard Stallman and the Free Software Foundation have criticized the Debian project for hosting the non-free repository and because the contrib and non-free areas are easily accessible,[146][147] an opinion echoed by some in Debian including the former project leader Wichert Akkerman.[148] The internal dissent in the Debian project regarding the non-free section has persisted,[149] but the last time it came to a vote in 2004, the majority decided to keep it.[150]

Multimedia support

Multimedia support has been problematic in Debian regarding codecs threatened by possible patent infringements, without sources or under too restrictive licenses,[151] and regarding technologies such as Adobe Flash.[75] Even though packages with problems related to their distribution could go into the non-free area, software such as libdvdcss is not hosted at Debian.[152]

A notable third party repository exists, formerly named debian-multimedia.org,[153][154][155] providing software not present in Debian such as Windows codecs, libdvdcss and the Adobe Flash Player.[156] Even though this repository is maintained by Christian Marillat, a Debian developer, it is not part of the project and is not hosted on a Debian server. The repository provides packages already included in Debian, interfering with the official maintenance. Eventually, project leader Stefano Zacchiroli asked Marillat to either settle an agreement about the packaging or to stop using the "Debian" name.[157] Marillat chose the latter and renamed the repository to deb-multimedia.org. The repository was so popular that the switchover was announced by the official blog of the Debian project.[158]

Hardware support

Hardware requirements

Hardware requirements are at least those of the kernel and the GNU toolsets.[159] Debian's recommended system requirements depend on the level of installation, which corresponds to increased numbers of installed components:[160]

| Type | Minimum RAM size | Recommended RAM size | Minimum processor clock speed (IA-32) | Hard drive capacity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non desktop | 128 MB | 512 MB | 2 GB | |

| Desktop | 256 MB | 1 GB | 1 GHz | 10 GB |

The real minimum memory requirements depend on the architecture and may be much less than the numbers listed in this table. It is possible to install Debian with 60 MB of RAM for x86-64;[160] the installer will run in low memory mode and it is recommended to create a swap partition.[27] The installer for z/Architecture requires about 20 MB of RAM, but relies on network hardware.[160][161] Similarly, disk space requirements, which depend on the packages to be installed, can be reduced by manually selecting the packages needed.[160] As of August 2014, no Pure Blend exists that would lower the hardware requirements easily.[162]

It is possible to run graphical user interfaces on older or low-end systems, but the installation of window managers instead of desktop environments is recommended, as desktop environments are more resource-intensive. Requirements for individual software vary widely and must be considered, with those of the base operating environment.[160]

Architecture ports

Official ports

As of the Stretch release, the official ports are:[163]

- amd64: x86-64 architecture with 64-bit userland and supporting 32-bit software

- arm64: ARMv8-A architecture[164]

- armel: Little-endian ARM architecture (ARMv4T instruction set)[165] on various embedded systems (embedded application binary interface (EABI))

- armhf: ARM hard-float architecture (ARMv7 instruction set) requiring hardware with a floating-point unit

- i386: IA-32 architecture with 32-bit userland, compatible with x86-64 machines[159]

- mips: Big-endian MIPS architecture

- mips64el: Little-endian 64 bit MIPS

- mipsel: Little-endian MIPS

- ppc64el: Little-endian PowerPC architecture supporting POWER7+ and POWER8 CPUs[164]

- s390x: z/Architecture with 64-bit userland, intended to replace s390[166]

Unofficial ports

Unofficial ports are available as part of the unstable distribution:[163]

- alpha: DEC Alpha architecture

- hppa: HP PA-RISC architecture

- hurd-i386: GNU Hurd kernel on IA-32 architecture

- ia64: Intel Itanium

- kfreebsd-amd64: Kernel of FreeBSD on x86-64 architecture

- kfreebsd-i386: Kernel of FreeBSD on IA-32 architecture

- m68k: Motorola 68k architecture on Amiga, Atari, Macintosh and various embedded VME systems

- powerpc: 32-bit PowerPC

- powerpcspe: PowerPCSPE architecture, incompatible with PowerPC

- ppc64: PowerPC64 architecture supporting 64-bit PowerPC CPUs with VMX

- riscv64: 64-bit RISC-V

- sh4: Hitachi SuperH architecture

- sparc64: Sun SPARC architecture with 64-bit userland

- x32: x32 ABI userland for x86-64[167]

Embedded systems

Debian supports a variety of ARM-based NAS devices. The NSLU2 was supported by the installer in Debian 4.0 and 5.0,[168] and Martin Michlmayr is providing installation tarballs since version 6.0.[169] Other supported NAS devices are the Buffalo Kurobox Pro,[170] GLAN Tank, Thecus N2100[171] and QNAP Turbo Stations.[170]

Devices based on the Kirkwood system on a chip (SoC) are supported too, such as the SheevaPlug plug computer and OpenRD products.[172] There are efforts to run Debian on mobile devices, but this is not a project goal yet since the Debian Linux kernel maintainers would not apply the needed patches.[173] Nevertheless, there are packages for resource-limited systems.[174]

There are efforts to support Debian on wireless access points.[175] Debian is known to run on set-top boxes.[176] Work is ongoing to support the AM335x processor,[177] which is used in electronic point of service solutions.[178] Debian may be customized to run on cash machines.[179]

BeagleBoard, a low-power open-source hardware single-board computer (made by Texas Instruments) has switched to Debian Linux preloaded on its Beaglebone Black board's flash.

Support for communities

Localization

Several parts of Debian are translated into languages other than American English, including package descriptions, configuration messages, documentation and the website.[180] The level of software localization depends on the language, ranging from the highly supported German and French to the hardly translated Creek and Samoan.[181] The installer is available in 73 languages.[182]

Virtual communities

Debian provides packages made for virtual communities. The Facebook and Twitter application interfaces are available to programmers;[183][184] the Pidgin messaging client used a custom plugin for Facebook until the networking site added support for XMPP.[185] Debian 5.0 Lenny was the last release supporting Tencent QQ.[186][187] Communication with Skype is possible using software in the contrib area.[188]

Policies

Debian is known for its manifesto,[189][190] social contract,[190][191][192] and policies.[193] Debian's policies and team efforts focus on collaborative software development and testing processes.[5] As a result of its policies, a new major release tends to occur every two years with revision releases that fix security issues and important problems.[118][77]

Organization

| General Resolution | |||||||||||||||

| elect↓ | override↓ | ||||||||||||||

| Leader | |||||||||||||||

| ↓appoint | |||||||||||||||

| Delegate | |||||||||||||||

| ↓decide | |||||||||||||||

| Developer | propose↑ | ||||||||||||||

The Debian project is a volunteer organization with three foundational documents:

- The Debian Social Contract defines a set of basic principles by which the project and its developers conduct affairs.[141]

- The Debian Free Software Guidelines define the criteria for "free software" and thus what software is permissible in the distribution. These guidelines have been adopted as the basis of the Open Source Definition. Although this document can be considered separate, it formally is part of the Social Contract.[141]

- The Debian Constitution describes the organizational structure for formal decision-making within the project, and enumerates the powers and responsibilities of the Project Leader, the Secretary and other roles.[49]

| Historical population | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | DD | ±% |

| 1999 | 347 | — |

| 2000 | 347 | +0.0% |

| 2001 | ? | — |

| 2002 | 939 | — |

| 2003 | 831 | −11.5% |

| 2004 | 911 | +9.6% |

| 2005 | 965 | +5.9% |

| 2006 | 972 | +0.7% |

| 2007 | 1,036 | +6.6% |

| 2008 | 1,075 | +3.8% |

| 2009 | 1,013 | −5.8% |

| 2010 | 886 | −12.5% |

| 2011 | 911 | +2.8% |

| 2012 | 948 | +4.1% |

| 2013 | 988 | +4.2% |

| 2014 | 1,003 | +1.5% |

| 2015 | 1,033 | +3.0% |

| 2016 | 1,023 | −1.0% |

| 2017 | 1,062 | +3.8% |

| 2018 | 1,001 | −5.7% |

| Source: Debian Voting Information | ||

Debian developers are organized in a web of trust.[194] There are at present about one thousand active Debian developers,[195][196] but it is possible to contribute to the project without being an official developer.[197]

The project maintains official mailing lists and conferences for communication and coordination between developers.[112][198] For issues with single packages and other tasks,[199] a public bug tracking system is used by developers and end users. Internet Relay Chat channels (primarily on the Open and Free Technology Community (OFTC) and freenode networks) are also used for communication among developers[112] and to provide real time help.[200]

Debian is supported by donations made to organizations authorized by the leader.[49] The largest supporter is Software in the Public Interest, the owner of the Debian trademark, manager of the monetary donations[201] and umbrella organization for various other community free software projects.[202]

A Project Leader is elected once per year by the developers. The leader has special powers, but they are not absolute, and appoints delegates to perform specialized tasks. Delegates make decisions as they think is best, taking into account technical criteria and consensus. By way of a General Resolution, the developers may recall the leader, reverse a decision made by the leader or a delegate, amend foundational documents and make other binding decisions.[49] The voting method is based on the Schulze method (Cloneproof Schwartz Sequential Dropping).[50]

Project leadership is distributed occasionally. Branden Robinson was helped by the Project Scud, a team of developers that assisted the leader,[204] but there were concerns that such leadership would split Debian into two developer classes.[205] Anthony Towns created a supplemental position, Second In Charge (2IC), that shared some powers of the leader.[206] Steve McIntyre was 2IC and had a 2IC himself.[207]

One important role in Debian's leadership is that of a release manager.[208] The release team sets goals for the next release, supervises the processes and decides when to release. The team is led by the next release managers and stable release managers.[209] Release assistants were introduced in 2003.[210]

Developer recruitment, motivation, and resignation

The Debian project has an influx of applicants wishing to become developers.[211] These applicants must undergo a vetting process which establishes their identity, motivation, understanding of the project's principles, and technical competence.[212] This process has become much harder throughout the years.[213]

Debian developers join the project for many reasons. Some that have been cited include:

- Debian is their main operating system and they want to promote Debian[214]

- To improve the support for their favorite technology[215]

- They are involved with a Debian derivative[216]

- A desire to contribute back to the free-software community[217]

- To make their Debian maintenance work easier[218]

Debian developers may resign their positions at any time or, when deemed necessary, they can be expelled.[49] Those who follow the retiring protocol are granted the "emeritus" status and they may regain their membership through a shortened new member process.[219]

Development procedures

| upstream | |||

| ↓ | packaging | ||

| package | |||

| ↓ | upload | ||

| incoming | |||

| ↓ | checks | ||

| unstable | |||

| ↓ | migration | ||

| testing | |||

| ↓ | freeze | ||

| frozen | |||

| ↓ | release | ||

| stable | |||

Each software package has a maintainer that may be either one person or a team of Debian developers and non-developer maintainers.[220][221] The maintainer keeps track of upstream releases, and ensures that the package coheres with the rest of the distribution and meets the standards of quality of Debian. Packages may include modifications introduced by Debian to achieve compliance with Debian Policy, even to fix non-Debian specific bugs, although coordination with upstream developers is advised.[219]

The maintainer releases a new version by uploading the package to the "incoming" system, which verifies the integrity of the packages and their digital signatures. If the package is found to be valid, it is installed in the package archive into an area called the "pool" and distributed every day to hundreds of mirrors worldwide. The upload must be signed using OpenPGP-compatible software.[112] All Debian developers have individual cryptographic key pairs.[222] Developers are responsible for any package they upload even if the packaging was prepared by another contributor.[223]

Initially, an accepted package is only available in the unstable branch.[112] For a package to become a candidate for the next release, it must migrate to the Testing branch by meeting the following:[224]

- It has been in unstable for a certain length of time that depends on the urgency of the changes.

- It does not have "release-critical" bugs, except for the ones already present in Testing. Release-critical bugs are those considered serious enough that they make the package unsuitable for release.

- There are no outdated versions in unstable for any release ports.

- The migration does not break any packages in Testing.

- Its dependencies can be satisfied by packages already in Testing or by packages being migrated at the same time.

- The migration is not blocked by a freeze.

Thus, a release-critical bug in a new version of a shared library on which many packages depend may prevent those packages from entering Testing, because the updated library must meet the requirements too.[225] From the branch viewpoint, the migration process happens twice per day, rendering Testing in perpetual beta.[112]

Periodically, the release team publishes guidelines to the developers in order to ready the release. A new release occurs after a freeze, when all important software is reasonably up-to-date in the Testing branch and any other significant issues are solved. At that time, all packages in the testing branch become the new stable branch.[112] Although freeze dates are time-based,[77] release dates are not, which are announced by the release managers a couple of weeks beforehand.[226]

A version of a package can belong to more than one branch, usually testing and unstable. It is possible for a package to keep the same version between stable releases and be part of oldstable, stable, testing and unstable at the same time.[227] Each branch can be seen as a collection of pointers into the package "pool" mentioned above.[112]

Security

The Debian project handles security through public disclosure rather than through obscurity. Debian security advisories are compatible with the Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures dictionary, are usually coordinated with other free software vendors and are published the same day a vulnerability is made public.[228][229] There used to be a security audit project that focused on packages in the stable release looking for security bugs;[230] Steve Kemp, who started the project, retired in 2011 but resumed his activities and applied to rejoin in 2014.[231][232]

The stable branch is supported by the Debian security team; oldstable is supported for one year.[114] Although Squeeze is not officially supported, Debian is coordinating an effort to provide long-term support (LTS) until February 2016, five years after the initial release, but only for the IA-32 and x86-64 platforms.[233] Testing is supported by the testing security team, but does not receive updates in as timely a manner as stable.[234] Unstable's security is left for the package maintainers.[114]

The Debian project offers documentation and tools to harden a Debian installation both manually and automatically.[235] Security-Enhanced Linux and AppArmor support is available but disabled by default.[170] Debian provides an optional hardening wrapper, and does not harden all of its software by default using gcc features such as PIE and buffer overflow protection, unlike operating systems such as OpenBSD,[236] but tries to build as many packages as possible with hardening flags.[16]

2008 OpenSSL vulnerability

In May 2008, it was revealed that a Debian developer discovered that the OpenSSL package distributed with Debian and derivatives such as Ubuntu, made a variety of security keys vulnerable to a random number generator attack, since only 32,767 different keys were generated.[237][238][239] The security weakness was caused by changes made in 2006 by another Debian developer in response to memory debugger warnings.[239][240] The complete resolution procedure was cumbersome because patching the security hole was not enough; it involved regenerating all affected keys and certificates.[241]

Cost of development

The cost of developing all of the packages included in Debian 5.0 Lenny (323 million lines of code) has been estimated to be about US$8 billion, using one method based on the COCOMO model.[11] As of 2016, Black Duck Open Hub estimates that the current codebase (74 million lines of code) would cost about US$1.4 billion to develop, using a different method based on the same model.[242][243]

Derivatives

Debian is one of the most popular Linux distributions, and many other distributions have been created from the Debian codebase, including Ubuntu and Knoppix.[244] As of 2018, DistroWatch lists 141 active Debian derivatives.[245] The Debian project provides its derivatives with guidelines for best practices and encourages derivatives to merge their work back into Debian.[246][247]

See also

References

Citations

- ↑ "Updated Debian 9: 9.5 released". Debian News. Debian. 2018-07-14. Retrieved 2018-07-15.

- ↑ "Debian -- Ports".

- ↑ "RISC-V - Debian Wiki". Retrieved 2018-01-24.

- ↑ "Debian -- Debian GNU/Hurd".

- 1 2 "Chapter 1 – Definitions and overview". The Debian GNU/Linux FAQ. Debian. Retrieved 2008-05-12.

- ↑ "Debian -- About". Debian. Debian. Retrieved 12 June 2017.

- 1 2 3 "ChangeLog". ibiblio. Retrieved 2016-08-18.

- ↑ "Chapter 3 – Debian Releases". A Brief History of Debian. Debian Documentation Team. Retrieved 10 February 2016.

- ↑ "A Brief History of Debian – A Detailed History". Retrieved October 13, 2015.

- ↑ "debian-devel". Debian.

- 1 2 Amor, J. J.; Robles, G.; González-Barahona, J. M.; Rivas, F.: Measuring Lenny: the size of Debian 5.0 ResearchGate

- 1 2 "Debian – Packages". Debian. Retrieved 2014-06-22.

- ↑ "Debian Moves to LibreOffice". Debian. Retrieved 2012-03-05.

- ↑ Noyes, Katherine (2012-01-11). "Debian Linux Named Most Popular Distro for Web Servers". PC World. Retrieved 2013-02-14.

- ↑ "Usage statistics and market share of Linux for websites". W3Techs.com. Retrieved 2014-06-10.

- 1 2 3 "Chapter 2. What's new in Debian 7.0". Release Notes for Debian 7.0 (wheezy), 32-bit PC. Debian. Retrieved 2014-05-27.

- ↑ "Debian GNU/Hurd". Debian. 2014-05-01. Retrieved 2014-06-10.

- ↑ "architecture requalification status for wheezy". Debian. Retrieved 2014-08-15.

- ↑ "Virtual Package: linux-image". Debian. Retrieved 2014-08-15.

- ↑ "Chapter 2 – Debian kernel source". Debian Linux Kernel Handbook. Alioth. 2013-12-14. Retrieved 2014-08-15.

- ↑ "Unofficial non-free CDs including firmware packages". Debian. Retrieved 2014-08-16.

- ↑ "Debian on CDs". Debian. 2014-05-10. Retrieved 2014-05-27.

- 1 2 3 "Downloading Debian CD images with jigdo". Debian. 2014-05-10. Retrieved 2014-05-26.

- ↑ "Downloading Debian CD/DVD images via HTTP/FTP". Debian. 2014-05-17. Retrieved 2014-05-26.

- ↑ "Installing Debian GNU/Linux via the Internet". Debian. Retrieved 2008-12-11.

- ↑ "4.3. Preparing Files for USB Memory Stick Booting". Debian GNU/Linux Installation Guide. Debian. 2010. Retrieved 2014-05-27.

- 1 2 "6.3. Using Individual Components". Debian GNU/Linux Installation Guide. Debian. 2013. Archived from the original on December 24, 2013. Retrieved 2014-05-30.

- ↑ Watson, J.A. (2013-05-28). "Debian Linux 7.0 Wheezy: Hands on". ZDNet. Retrieved 2014-06-10.

For the CD images, it is useful to know that Debian supports a number of different desktops, including GNOME, KDE, Xfce and LXDE, and there is a different 'disk 1' image for each of these desktops.

- ↑ "Chapter 1 – Introduction – What is the Debian Project?". A Brief History of Debian. Debian. 2013-05-04. Retrieved 2014-06-22.

- ↑ Murdock, Ian A. (1993-08-16). "New release under development; suggestions requested". Newsgroup: comp.os.linux.development. Usenet: CBusDD.MIK@unix.portal.com. Retrieved 2012-06-13.

- ↑ Nixon, Robin (2010). Ubuntu: Up and Running. O'Reilly Media. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-596-80484-8. Retrieved 2014-06-22.

- ↑ Hillesley, Richard (2007-11-02). "Debian and the grass roots of Linux". IT Pro. Retrieved 2014-05-25.

- ↑ Scheetz 1998, p. 17.

- ↑ "Release-0.91". ibiblio. 1994-01-31. Retrieved 2014-07-03.

- ↑ Murdock, Ian A. (1994-01-06). "The Debian Linux Manifesto". ibiblio. Retrieved 2014-07-17.

- 1 2 3 4 "Chapter 3 – Debian Releases". A Brief History of Debian. Debian. 2013-05-04. Retrieved 2014-06-22.

- ↑ Stallman, Richard (1996-04-28). "The FSF is no longer sponsoring Debian". Newsgroup: comp.os.linux.misc. Usenet: gnusenet199604280427.AAA00388@delasyd.gnu.ai.mit.edu. Retrieved 2014-08-22.

- ↑ Scheetz 1998, p. 18.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Chapter 4 – A Detailed History". A Brief History of Debian. Debian. 2013-05-04. Retrieved 2014-08-01.

- ↑ Krafft 2005, pp. 31–32.

- 1 2 Hertzog 2013, p. 9.

- ↑ Perens, Bruce (1997-07-05). "Debian's 'Social Contract' with the Free Software Community". debian-announce (Mailing list). Debian. Retrieved 2014-08-01.

- ↑ "It's Time to Talk About Free Software Again". Archived from the original on July 16, 2014.

- 1 2 Scheetz 1998, p. 19.

- ↑ Perens, Bruce (2000-11-01). "Building Tiny Linux Systems with Busybox–Part I". Linux Journal. Retrieved 2014-06-05.

- ↑ Perens, Bruce (1998-03-18). "I am leaving Debian". debian-user (Mailing list). Debian. Retrieved 2014-06-05.

- ↑ Perens, Bruce (1997-12-01). "Ian Jackson is the next Debian Project Leader". debian-announce (Mailing list). Debian. Retrieved 2014-08-02.

- ↑ Grobman, Igor (1998-07-14). "debian-hurd@lists.debian.org is up!". debian-hurd (Mailing list). Debian. Retrieved 2014-08-02.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Constitution for the Debian Project (v1.4)". Debian. Retrieved 2014-02-25.

- 1 2 "Debian Voting Information". Debian. 2014-02-18. Retrieved 2014-06-03.

- ↑ Coleman 2013, p. 141.

- ↑ Akkerman, Wichert (1999-10-17). "New maintainer proposal". debian-project (Mailing list). Debian. Retrieved 2014-08-02.

- ↑ Lohner, Nils (1999-11-09). "New Linux distribution brings Debian to the desktop". debian-commercial (Mailing list). Debian. Retrieved 2014-08-02.

- ↑ "Debian GNU/Linux 2.2, the 'Joel "Espy" Klecker' release, is officially released". Debian. 2000-08-15. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- ↑ Laronde, Thierry (2000-05-15). "First Debian Conference : the program". debian-devel-announce (Mailing list). Debian. Retrieved 2014-08-02.

- ↑ Lemos, Robert (2001-05-10). "HP settles on Debian Linux". CNET News. Retrieved 2014-08-19.

- ↑ Krafft 2005, p. 33.

- ↑ Lettice, John (2002-07-23). "Debian GNU/Linux 3.0 released". The Register. Retrieved 2014-08-19.

- ↑ LeMay, Renai (2005-03-18). "Debian leaders: Faster release cycle required". ZDNet. Retrieved 2014-08-03.

- ↑ "Ubuntu vs. Debian, reprise". Ian Murdock. April 20, 2005. Archived from the original on August 19, 2014. Retrieved June 5, 2014.

- ↑ Orlowski, Andrew (2003-12-02). "Hackers used unpatched server to breach Debian". The Register. Retrieved 2014-08-03.

- ↑ Coleman 2013, p. 150.

- ↑ Orlowski, Andrew (2005-03-14). "Debian drops mainframe, Sparc development". The Register. Retrieved 2014-08-03.

- ↑ Verhelst, Wouter (2005-08-21). "Results of the meeting in Helsinki about the Vancouver proposal". debian-devel-announce (Mailing list). Debian. Retrieved 2014-08-03.

- ↑ Langasek, Steve (2005-03-14). "Bits (Nybbles?) from the Vancouver release team meeting". debian-devel-announce (Mailing list). Debian. Retrieved 2014-08-03.

- ↑ Coleman 2013, pp. 153–154.

- ↑ Jarno, Aurélien (2005-03-14). "Re: Bits (Nybbles?) from the Vancouver release team meeting". debian-devel (Mailing list). Debian. Retrieved 2014-08-03.

- ↑ Blache, Julien (2005-03-14). "Re: Bits (Nybbles?) from the Vancouver release team meeting". debian-devel (Mailing list). Debian. Retrieved 2014-08-03.

- ↑ "Chapter 2 – What's new in Debian GNU/Linux 3.1". Release Notes for Debian GNU/Linux 3.1 (`sarge'), Intel x86. Debian. 2006-09-18. Retrieved 2010-08-05.

- ↑ Hoover, Lisa (2006-10-10). "Behind the Debian and Mozilla dispute over use of Firefox". Linux.com. Retrieved 2009-02-09.

- ↑ Sanchez, Roberto C. (2006-10-15). "Re: Will IceWeasel be based on a fork or on vanilla FireFox?". debian-devel (Mailing list). Debian. Retrieved 2014-08-03.

- ↑ Hoffman, Chris (2016-02-24). "'Iceweasel' will be renamed 'Firefox' as relations between Debian and Mozilla thaw". PC World. Retrieved 2016-03-27.

- ↑ "Press Information". Dunc-Tank. 2006-09-19. Archived from the original on 2006-10-10. Retrieved 2014-08-24.

- ↑ Vaughan-Nichols, Steven J. (2006-12-18). "Disgruntled Debian Developers Delay Etch". eWeek. Retrieved 2014-08-24.

- 1 2 "Debian GNU/Linux 5.0 released". Debian. 2009-02-14. Retrieved 2009-02-15.

- ↑ "Appendix C. Lenny dedicated to Thiemo Seufer". Release Notes for Debian GNU/Linux 5.0 (lenny), Intel x86. Debian. 2009-02-14. Retrieved 2014-05-25.

- 1 2 3 "Debian decides to adopt time-based release freezes". Debian. 2009-07-29. Retrieved 2009-09-12.

- ↑ "Debian GNU/Linux 6.0 'Squeeze' release goals". Debian. 2009-07-30. Retrieved 2009-12-01.

- 1 2 "Backports service becoming official". Debian. 2010-09-05. Retrieved 2014-06-17.

- 1 2 "Debian 6.0 'Squeeze' released". Debian. 2011-02-06. Retrieved 2011-02-06.

- ↑ "Debian 7.0 'Wheezy' released". Debian. 2013-05-04. Retrieved 2013-05-05.

- ↑ "Debian 8 'Jessie' Released". Debian. 2015-04-25. Retrieved 2015-10-27.

- ↑ "Debian 9.0 'Stretch' released". Debian. 2017-06-17. Retrieved 2017-06-25.

- ↑ Debian 9's release date, DistroWatch

- ↑ "Unstable packages' upgrade announcements". Debian. Retrieved 2014-11-19.

- ↑ "Awards". Debian. Retrieved 2008-11-02.

- ↑ "2011 LinuxQuestions.org Members Choice Award Winners". LinuxQuestions.org. 2012-02-09. Retrieved 2014-06-06.

- ↑ "The best Linux distro of 2011!". TuxRadar. 2011-08-04. Retrieved 2014-06-06.

- ↑ "Best of the Net Awards, October 1998 – Focus On Linux". The Mining Company. 1999-05-04. Archived from the original on 1999-05-04. Retrieved 2014-06-06.

- ↑ Zarkos, Stephen (2015-12-02). "Announcing availability of Debian GNU/Linux as an endorsed distribution in Azure Marketplace". azure.microsoft.com. Microsoft. Retrieved 2016-04-10.

- ↑ Bhartiya, Swapnil (2015-12-02). "Microsoft brings Debian GNU/Linux to Azure cloud". CIO.com. IDG Enterprise. Retrieved 2016-04-10.

- ↑ "Point Releases - Debian Wiki". Debian Release Team. Retrieved 2017-09-27.

- ↑ "LTS - Debian Wiki". Debian LTS Team. 3 July 2018. Retrieved 18 August 2018.

- ↑ "Package: mate-desktop (1.8.1+dfsg1-1~bpo70+1)". Debian. Retrieved 2014-07-06.

- ↑ "Debian – Details of package cinnamon in jessie". packages.debian.org. Retrieved 2015-09-06.

- ↑ "Virtual Package: x-window-manager". Debian. Retrieved 2014-05-27.

- ↑ Larabel, Michael (2012-08-08). "Debian Now Defaults To Xfce Desktop". Phoronix. Retrieved 2012-08-27.

- ↑ Stahie, Silviu (2013-11-05). "Debian 8.0 'Jessie' Ditches GNOME and Adopts Xfce". Softpedia. Retrieved 2014-11-22.

- ↑ Hess, Joey (2014-09-19). "switch default desktop to GNOME". Alioth. Retrieved 2014-11-03.

- ↑ "Live install images". Debian. 2013-10-27. Retrieved 2013-12-07.

- ↑ "Debian Live Manual". Debian. 2013. Archived from the original on February 14, 2014. Retrieved 2014-07-06.

- 1 2 3 4 "Chapter 2. Debian package management". Debian Reference. Debian. 2013-12-03. Retrieved 2014-05-29.

- ↑ "Package: dpkg (1.16.15) [security] [essential]". Debian. Retrieved 2014-06-18.

- ↑ "dpkg". Debian. 2012-06-05. Retrieved 2014-06-18.

- ↑ "gdebi". Launchpad. Retrieved 2014-06-19.

- ↑ Thomas, Keir (2009-04-13). "10 Expert Ubuntu Tricks". PC World. Retrieved 2014-06-19.

- ↑ "Package: software-center (5.1.2debian3.1)". Debian. Retrieved 2014-06-19.

- ↑ "Package: synaptic (0.75.13)". Debian. Retrieved 2014-06-19.

- ↑ "Package: apper (0.7.2-5)". Debian. Retrieved 2014-06-19.

- 1 2 "Debian Releases". Debian. Retrieved 2014-06-22.

- ↑ Vaughan-Nichols, Steven J. (2013-05-05). "The new Debian Linux 7.0 is now available". ZDNet. Retrieved 2014-07-08.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 "Chapter 4. Resources for Debian Developers". Debian Developer's Reference. Debian. Retrieved 2008-10-31.

- ↑ "Frequently Asked Questions". Debian. Retrieved 2014-07-09.

- 1 2 3 "Debian security FAQ". Debian. 2007-02-28. Retrieved 2008-10-21.

- ↑ "snapshot.debian.org". Debian. Retrieved 2014-07-09.

- ↑ "ChangeLog". stretch. Debian. 2017-06-17. Retrieved 2018-07-14.

- ↑ "ChangeLog". jessie. Debian. 2017-05-06. Retrieved 2017-06-17.

- 1 2 Hertzog, Raphaël (2013). The Debian Administrator's Handbook. Freexian. ISBN 979-10-91414-03-6. Retrieved 2014-06-22.

- ↑ "Release". etch. Debian. 2010-05-22. Retrieved 2014-06-05.

- ↑ Schulze, Martin (1998-08-24). "Naming of new 2.0 release". debian-devel (Mailing list). Debian. Retrieved 2014-07-26.

- ↑ "GNU Coding Standards: Releases". GNU. 2014-05-13. Retrieved 2014-05-25.

You should identify each release with a pair of version numbers, a major version and a minor. We have no objection to using more than two numbers, but it is very unlikely that you really need them.

- ↑ Brockschmidt, Marc (2009-02-15). "Debian squeeze waiting for development". debian-devel-announce (Mailing list). Debian. Retrieved 2009-02-15.

- ↑ "ChangeLog". wheezy. Debian. 2016-06-04. Retrieved 2016-12-14.

- ↑ "Updated Debian 7: 7.7 released". Debian. 2014-10-18. Retrieved 2014-10-20.

- ↑ Wiltshire, Jonathan (2014-11-09). "Release Team Sprint Results". lists.debian.org. Debian. Retrieved 2017-01-10.

- ↑ "Chapter 6 – The Debian FTP archives". The Debian GNU/Linux FAQ. Debian. 2013-06-02. Retrieved 2013-06-03.

- ↑ Wiltshire, Jonathan (2016-07-06). "Bits from the release team: Winter is Coming (but not to South Africa)". lists.debian.org. Debian. Retrieved 2017-04-07.

- ↑ Monfort, Emilio Pozuelo (2018-04-16). "Bits from the release team: full steam ahead towards buster)". lists.debian.org. Debian. Retrieved 2018-04-27.

- 1 2 "Chapter 2. What are Debian Pure Blends?". Debian Pure Blends. Debian. Retrieved 2014-05-27.

- ↑ "Debian Jr. Project". Debian. 2014-04-30. Retrieved 2014-06-16.

- ↑ Armstrong, Ben (2011-07-06). "Re: Difference between blends and remastered systems". debian-blends (Mailing list). Debian. Retrieved 2014-06-16.

- ↑ "GNU/art".

- ↑ "Logo credit".

- ↑ "Debian Logo Contest".

- ↑ "[PROPOSED] Swap the "open" and "official" versions of the new logo".

- ↑ "Debian Chooses Logo". Archived from the original on February 18, 2015.

- ↑ "Origins of the Debian logo".

- ↑ Krafft 2005, p. 66.

- ↑ Toy Story (Billboard). Pixar. Archived from the original on November 10, 2013. Retrieved August 20, 2014.

- ↑ "Debian: 17 ans de logiciel libre, 'do-ocracy' et démocratie" (PDF). Stefano Zacchiroli. 2010-12-04. p. 6. Retrieved 2014-10-21.

- ↑ "License information". Debian. Retrieved 2009-02-28.

- 1 2 3 "Chapter 2 – The Debian Archive". Debian Policy Manual. Debian. October 28, 2013. Archived from the original on July 13, 2014. Retrieved July 9, 2014.

- ↑ "General Resolution: Why the GNU Free Documentation License is not suitable for Debian main". Debian. 2006. Retrieved 2014-07-02.

- ↑ "Package: fglrx-driver (1:12-6+point-3) [non-free]". Debian. Retrieved 2014-07-02.

- ↑ "Explaining Why We Don't Endorse Other Systems". GNU. Retrieved 2014-06-19.

- ↑ Stallman, Richard (2007-10-06). "Re: Debian vs gNewSense – FS criteria". gnuherds-app-dev (Mailing list). lists.nongnu.org. Retrieved 2014-07-09.

What makes Debian unacceptable is that its inclusion of non-free software is not a mistake.

- ↑ Akkerman, Wichert (1999-06-21). "Moving contrib and non-free of master.debian.org". debian-vote (Mailing list). Debian. Retrieved 2014-08-04.

- ↑ Wise, Paul (2014-03-22). "non-free?". debian-vote (Mailing list). Debian. Retrieved 2014-08-16.

- ↑ "General Resolution: Status of the non-free section". Debian. 2004. Retrieved 2009-09-28.

- ↑ Mejia, Andres (2012-03-18). "Diff for 'MultimediaCodecs'". Debian Wiki. Retrieved 2014-10-16.

- ↑ "RFP: libdvdcss – Library to read scrambled DVDs". Debian BTS. 2002-07-25. Retrieved 2014-07-09.

- ↑ Gilbertson, Scott (2009-02-16). "'Lenny': Debian for the masses?". The Register. Retrieved 2014-07-13.

- ↑ Granneman, Scott (2008-02-06). "Cool APT Repositories for Ubuntu and Debian". Linux Magazine. Retrieved 2014-07-13.

- ↑ Nestor, Marius (2012-03-19). "Window Maker Live CD 2012-03-18 Available for Download". Softpedia. Retrieved 2014-11-22.

- ↑ "Packages". deb-multimedia.org. Retrieved 2014-07-13.

- ↑ Zacchiroli, Stefano (2012-05-05). "on package duplication between Debian and debian-multimedia". pkg-multimedia-maintainers (Mailing list). Alioth. Retrieved 2014-07-13.

- ↑ "Remove unofficial debian-multimedia.org repository from your sources". Debian. 2013-06-14. Retrieved 2014-07-13.

- 1 2 "2.1. Supported Hardware". Debian GNU/Linux Installation Guide. Debian. 2015. Retrieved 2017-01-20.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "3.4. Meeting Minimum Hardware Requirements". Debian GNU/Linux Installation Guide. Debian. 2015. Retrieved 2017-01-20.

- ↑ "5.1. Booting the Installer on S/390". Debian GNU/Linux Installation Guide. Debian. 2015. Retrieved 2017-01-20.

- ↑ "Chapter 4. Existing Debian Pure Blends". Debian Pure Blends. Debian. 2013-06-19. Retrieved 2014-06-19.

- 1 2 "Buildd status for base-files". Debian. Retrieved 2018-03-24.

- 1 2 Wookey (2014-08-27). "Two new architectures bootstrapping in unstable – MBF coming soon". debian-devel-announce (Mailing list). Debian. Retrieved 2014-09-01.

- ↑ Wookey (2010-01-23). "Re: Identification of ARM chips". debian-embedded (Mailing list). Debian. Retrieved 2014-10-16.

- ↑ "Chapter 2. What's new in Debian 7.0". Release Notes for Debian 7.0 (wheezy), S/390. 2014-11-09. Retrieved 2015-01-28.

- ↑ Schepler, Daniel (2012-11-20). "X32Port". Debian Wiki. Retrieved 2014-10-17.

- ↑ Brown, Silas. "Upgrading your Slug LG #161". Linux Gazette. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- ↑ "Installing Debian on NSLU2". Martin Michlmayr. 2011-02-24. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- 1 2 3 "Chapter 2. What's new in Debian GNU/Linux 5.0". Release Notes for Debian GNU/Linux 5.0 (lenny), ARM. Debian. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- ↑ "Chapter 2 – What's new in Debian GNU/Linux 4.0". Release Notes for Debian GNU/Linux 4.0 ('etch'), ARM. Debian. 2007-08-16. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- ↑ "Chapter 2. What's new in Debian GNU/Linux 6.0". Release Notes for Debian GNU/Linux 6.0 (squeeze), ARM EABI. Debian. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- ↑ "Debian Project News – December 10th, 2012". Debian. 2012-12-10. Retrieved 2014-06-17.

- ↑ "Package: matchbox (1:5)". Debian. Retrieved 2014-06-17.

- ↑ Hess, Joey (2005-09-23). "DebianWRT". Debian Wiki. Retrieved 2014-10-17.

- ↑ "Debian Project News – December 2nd, 2013". Debian. 2013-12-02. Retrieved 2014-06-17.

- ↑ Liu, Ying-Chun (2012-01-27). "InstallingDebianOn TI BeagleBone". Debian Wiki. Retrieved 2014-10-17.

- ↑ "Enterprise Tablet Reference Design Kit". Texas Instruments. Archived from the original on June 12, 2014. Retrieved 2014-06-17.

- ↑ "Thieves Planted Malware to Hack ATMs". Brian Krebs. 2014-05-30. Retrieved 2014-06-17.

- ↑ "Central Debian translation statistics". Debian. Retrieved 2014-07-02.

- ↑ "Status of the l10n in Debian — ranking PO files between languages". Debian. Retrieved 2014-07-02.

- ↑ "Debian Installer 7.0 RC3 release". Debian. 2013-05-02. Retrieved 2013-05-02.

- ↑ "Debian – Package Search Results – facebook". Debian. Retrieved 2014-11-17.

- ↑ "Debian – Package Search Results – twitter". Debian. Retrieved 2014-11-17.

- ↑ "RM: pidgin-facebookchat – RoQA; unneeded". Debian BTS. 2013-05-08. Retrieved 2014-11-17.

- ↑ "libpurple0_2.4.3-4lenny8_i386.deb". Debian. 2010-11-07. Retrieved 2014-11-17.

- ↑ "File list of package libpurple0 in squeeze of architecture i386". Debian. Retrieved 2014-11-17.

- ↑ "Debian – Package Search Results – skype". Debian. Retrieved 2014-11-17.

- ↑ Murdock, Ian (1994-06-01). "A Brief History of Debian Appendix A – The Debian Manifesto". Debian. Retrieved 2015-12-26.

- 1 2 Gilbertson, Scott (2013-08-13). "No distro diva drama here: Penguinista favourite Debian turns 20". The Register. Retrieved 2014-05-30.

- ↑ Paul, Ryan (2008-12-30). "Why Ubuntu users should care about Debian". Ars Technica. Retrieved 2014-05-30.

- ↑ Brockmeier, Joe (2011-02-07). "Why Debian matters more than ever". Network World. Retrieved 2014-05-30.

- ↑ Brockmeier, Joe (2009-05-19). "Trademarks: Open Source Friendly (TM)". PC World. Retrieved 2014-05-30.

- ↑ Coleman 2013, p. 143.

- ↑ "Debian New Member – Status DD, upl". Debian. Retrieved 2014-06-21.

- ↑ "Debian New Member – Status DD, non-upl". Debian. Retrieved 2014-06-21.

- ↑ "How can you help Debian?". Debian. 2014-04-30. Retrieved 2014-06-03.

- ↑ "Index of /pub/debian-meetings". Debian. Retrieved 2014-07-16.

- ↑ "Debian bug tracking system pseudo-packages". Debian. 2013-12-08. Retrieved 2014-06-03.

- ↑ "Support". Debian. 2014-04-30. Retrieved 2014-06-03.

- ↑ "Donations to Software in the Public Interest". Debian. 2014-05-10. Retrieved 2014-06-03.

- ↑ "SPI Associated Projects". Software in the Public Interest. 2014-07-14. Retrieved 2014-07-16.

- ↑ "Chapter 2 – Leadership". A Brief History of Debian. Debian. 2013-05-04. Retrieved 2014-07-05.

- ↑ van Wolffelaar, Jeroen (2005-03-05). "Announcing project scud". debian-project (Mailing list). Debian. Retrieved 2014-07-17.

- ↑ Krafft 2005, p. 34.

- ↑ Towns, Anthony (2006-04-23). "Bits from the DPL". debian-devel-announce (Mailing list). Debian. Retrieved 2014-07-17.

- ↑ "Steve McIntyre's DPL platform, 2009". Debian. Retrieved 2014-07-17.

- ↑ O'Mahony, Siobhán; Ferraro, Fabrizio (2007). "The Emergence of Governance in an Open Source Community" (PDF). University of Alberta School of Business. p. 30. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-05-29. Retrieved 2008-11-01.

- ↑ "The Debian organization web page". Debian. Retrieved 2008-11-01.

- ↑ Towns, Anthony (2003-03-08). "Bits from the RM: Help Wanted, Apply Within". debian-devel-announce (Mailing list). Debian. Retrieved 2014-07-17.

- ↑ "Debian New Member – Statistics". Debian. Archived from the original on July 6, 2014. Retrieved 2014-06-03.

- ↑ "Debian New Maintainers". Debian. Retrieved 2008-10-31.

- ↑ Hertzog 2013, p. 13.

- ↑ Berg, Christoph (2009-01-10). "AM report for Alexander GQ Gerasiov". debian-newmaint (Mailing list). Debian. Retrieved 2014-07-18.

- ↑ Joeris, Steffen (2010-01-03). "AM report for Jakub Wilk [...]". debian-newmaint (Mailing list). Debian. Retrieved 2014-07-18.

- ↑ Wolf, Gunnar (2011-01-13). "AM report for Kamal Mostafa". debian-newmaint (Mailing list). Debian. Retrieved 2014-07-18.

- ↑ Faraone, Luke (2012-01-01). "AM report for vicho". debian-newmaint (Mailing list). Debian. Retrieved 2014-07-18.

- ↑ Wiltshire, Jonathan (2013-01-06). "AM report for Manuel A. Fernandez Montecelo". debian-newmaint (Mailing list). Debian. Retrieved 2014-07-18.

- 1 2 "Chapter 3. Debian Developer's Duties". Debian Developer's Reference. Debian. Retrieved 2014-07-19.

- ↑ "Chapter 3 – Binary packages". Debian Policy Manual. Debian. 2013-10-28. Retrieved 2014-07-19.

- ↑ "General Resolution: Endorse the concept of Debian Maintainers". Debian. 2007. Retrieved 2008-12-13.

- ↑ "Chapter 2. Applying to Become a Maintainer". Debian Developer's Reference. Debian. Retrieved 2010-10-09.

- ↑ Costela, Leo (2010-02-12). "DebianMentorsFaq". Debian Wiki. Retrieved 2014-10-17.

- ↑ "Chapter 5. Managing Packages". Debian Developer's Reference. Debian. Retrieved 2008-10-31.

- ↑ "Debian 'testing' distribution". Debian. Retrieved 2008-11-24.

- ↑ McGovern, Neil (2013-04-18). "FINAL release update". debian-devel-announce (Mailing list). Debian. Retrieved 2014-07-20.

- ↑ "Debian – Package Search Results – dict-bouvier". Debian. Retrieved 2014-06-04.

- ↑ "Security Information". Debian. Retrieved 2008-12-13.

- ↑ "Organizations Participating". MITRE. 2014-04-16. Retrieved 2014-06-05.

- ↑ "Debian Security Audit Project". Debian. 2014-03-15. Retrieved 2014-06-04.

- ↑ "Advisories". Steve Kemp. Retrieved 2014-08-18.

- ↑ "Steve Kemp". Debian. Retrieved 2014-08-18.

- ↑ Larabel, Michael (2014-04-18). "Debian To Maintain 6.0 Squeeze As An LTS Release". Phoronix. Retrieved 2014-07-21.

- ↑ "Debian testing security team". Debian. Archived from the original on October 5, 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-31.

- ↑ "Securing Debian Manual". Debian. Retrieved 2008-12-13.

- ↑ "Debian Secure by Default". Debian: SbD. Retrieved 2011-01-31.

- ↑ "DSA-1571-1 openssl: predictable random number generator". Debian. 2008-05-13. Retrieved 2008-10-31.

- ↑ "CVE-2008-0166". MITRE. Retrieved 2014-07-21.

- 1 2 Garfinkel, Simson (2008-05-20). "Alarming Open-Source Security Holes". MIT Technology Review. Retrieved 2014-07-21.

- ↑ "valgrind-clean the RNG". Debian BTS. 2006-04-19. Retrieved 2014-06-21.

- ↑ "When Private Keys are Public: Results from the 2008 Debian OpenSSL Vulnerability" (PDF). University of California, San Diego. 2009. Retrieved 2014-06-22.

- ↑ "Estimated Cost". Black Duck Open Hub. Retrieved 2016-01-06.

- ↑ "Package: ohcount (3.0.0-8 and others)". Debian. Retrieved 2016-01-06.

- ↑ Vaughan-Nichols, Steven J. (2009-12-16). "The Five Distros That Changed Linux". Linux Magazine. Retrieved 2013-02-14.

- ↑ "Based on Debian, status active". DistroWatch. Retrieved 2018-04-08.

- ↑ Halchenko, Yaroslav (2010-12-21). "Derivatives Guidelines". Debian Wiki. Retrieved 2014-10-17.

- ↑ Hertzog 2013, p. 429.

Sources

- Books

- Coleman, E. Gabriella (2013). "Two Ethical Moments in Debian". Coding Freedom: The Ethics and Aesthetics of Hacking (PDF). Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-14461-0. Retrieved 2014-07-31.

- Hertzog, Raphaël (2013). The Debian Administrator's Handbook. Lulu. ISBN 979-10-91414-02-9. Retrieved 2014-06-22.

- Krafft, Martin F. (2005). The Debian System. U.S.A.: No Starch Press. ISBN 1-59327-069-0. Retrieved 2014-08-04.

- Scheetz, Dale (1998). The Debian Linux User's Guide. Linux Press. ISBN 0-9659575-1-9.

- Webpage

- Wallen, Jack (2014). "Why aren't more people using Debian?". TechRepublic. Retrieved 2015-04-19.

External links

- Official website

- Debian wiki

- Debian at Curlie (based on DMOZ)

- Debian at DistroWatch