Daliyat al-Karmel

Daliat El Carmel

| |

|---|---|

|

| |

Daliat El Carmel | |

| Coordinates: 32°41′35″N 35°02′58″E / 32.69306°N 35.04944°ECoordinates: 32°41′35″N 35°02′58″E / 32.69306°N 35.04944°E | |

| Grid position | 154/233 PAL |

| District |

|

| Government | |

| • Type | Local council |

| • Head of Municipality | Rafik Halabi |

| Area | |

| • Total | 15,561 dunams (15.561 km2 or 6.008 sq mi) |

| Population (2017)[1] | |

| • Total | 17,201 |

| • Density | 1,100/km2 (2,900/sq mi) |

| Name meaning | "The hanging vine of Carmel[2] |

| Website | www.Daliat-carmel.org.il |

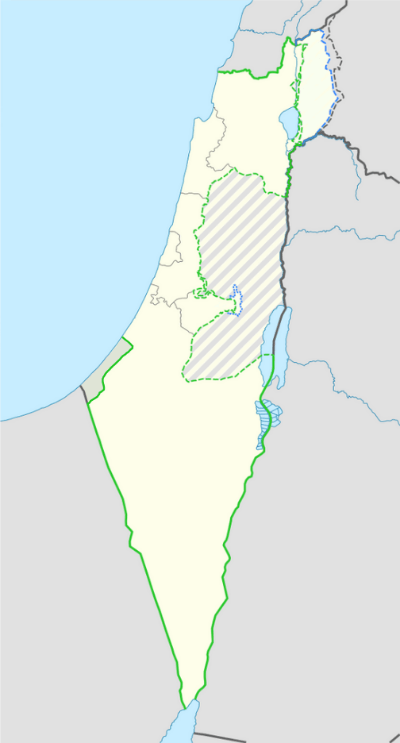

Daliyat El Karmel (Arabic: دَالِيَةِ ٱلْكَرْمِل, Hebrew: דַלְיַת אֶל-כַּרְמֶל) is a Druze town in the Haifa District of Israel, located around 20 km southeast of Haifa. In 2017 its population was 17,201.[1] Daliyat al-Karmel, situated on Mount Carmel, is the country’s largest and southernmost Druze town.[3]

History

In 1283 both Daliyat al-Karmel and Kh. Doubel (just south of Daliyat al-Karmel) were mentioned as part of the domain of the Crusaders, according to the hudna between the Crusaders in Acre and the Mamluk sultan Qalawun.[4]

In 1870 a local guide showed French explorer Victor Guérin extensive ruins located south of Daliyat al-Karmel, called Khirbet Doubel. The ruins were the most extensive on Mt. Carmel. Guérin thought it might be the town on Mt. Carmel mentioned by Pliny.[5] Conder and Kitchener surveyed the area and noted "traces of ruins" at a place SE of the village centre called Dubil.[6] Later excavations have found remains there from Iron Age I, Early Roman and Byzantine periods,[7] together with pottery from first century to the second–third centuries CE.[8]

Ottoman era

In the 17th century, during the Ottoman period, Druze came from the hill country near Aleppo, Syria to Daliyat al-Karmel (lit. “Vine of the Carmel"),[9] and in 1859 they were numbered by the English Consul Rogers to be 300 souls, who tilled twenty feddans.[10]

In 1870, the French explorer Victor Guérin visited the village. He found four hundred inhabitants, all Druze. The houses were mostly built of adobe, with only a few stone houses. The locals worshipped inside a cave, where the explorer was not allowed.[11]

In 1881, the Palestine Exploration Fund's Survey of Western Palestine described the village as a "stone village of moderate size on a knoll of one of the spurs running out of the main watershed of Carmel. On the south there is a well, and fine springs on the west, near Umm esh Shukf. On the north is a little plain or open valley cultivated with corn (Merjat ed Dalieh). The inhabitants are all Druses."[10] A population list from about 1887 showed that Daliyat al-Karmel had about 620 inhabitants; all Druze.[12]

British Mandate era

In the 1922 census of Palestine conducted by the British Mandate authorities, Daliat al-Carmel had a population of 993; 921 Druse and 21 Christians,[13] increasing in the 1931 census when Daliet el Karmil, together Deir el Muhraqa and Khirbat el Mansura had a total population of 1173; 1154 Druse, 11 Christians and 8 Muslims, in a total of 236 houses.[14]

In the 1945 statistics the population of Daliyat al-Karmel consisted of 2,060 Arabs,[15] (20 Christians and 2,040 classified as "Others", that is: Druze)[16] and the land area was 31,730 dunams, according to an official land and population survey.[15] Of this, 1,506 dunams were designated for plantations and irrigable land, 18,174 for cereals,[17] while 60 dunams were built-up areas.[18]

State of Israel

An Israeli census conducted in November 1948 found 2,932 residents. At the end of 1951 the figure dropped to 2,769.[19] The town was granted local council status in 1951. In 2003, Dalyat was merged with nearby Isfiya to create Carmel City.[20] In 2008, the communities became separate once again. The town is famous for its colorful market.[21]

In 2010, El Al, Israel's national airline, named one of its Boeing 767 airplanes Daliyat al-Karmel. Sheikh Muafak Tarif, leader of the Druze community, was presented with a miniature model of the plane at a special ceremony.[22]

Landmarks

The shrine of Abu Ibrahim, whom the Druze consider a prophet, is in the oldest part of the town. Close by, is the home of Sir Laurence Oliphant, who spent his summers there in the 1880s with his wife Alice, and his secretary Naftali Herz Imber.[23]

The Muharka Monastery located 2 kilometer southeast to Dalyat al-Karmel and marks the battle between prophet Elijah and the prophets of the Ba'al, it is belonging to the Carmelite Order.

The Carmel Center for Druze Heritage is a hands-on museum of the history, religion and culture of the Druze.[3][21]

In 2011, the Garden of the Mothers was inaugurated in Daliyat al-Karmel, symbolizing the sisterhood of Christian, Druze, Jewish, and Muslim women who work together in northern Israel. Forty-four trees were planted in memory of the 44 Israel Prison Services personnel who died in the Mount Carmel forest fire in 2010.[24]

Culture and sports

In 2012, a tennis school financed by the Freddie Krivine Foundation opened in Daliyat al-Karmel and 12 youngsters take part in a weekly co-existence program with children at the Israel Tennis Center in Yokneam.[25]

Mevo Carmel high-tech park

Daliyat al-Karmel and Isfiya joined Yokneam Illit and the Megiddo Regional Council to develop the Mevo Carmel Jewish-Arab Industrial Park to benefit from the existing high-tech ecosystem.[26][27]

Twin cities

In 2007, Daliyat al-Karmel signed a partnership agreement with Ungheni, Moldova. In 2008, the Ambassador of Moldova, Larisa Miculet visited Daliyat al-Karmel at the invitation of the mayor, Akram Hasson.[28]

Notable residents

- Majdi Halabi, Israeli missing soldier

- Ayoob Kara, Likud MK

- Amal Nasser el-Din, former Likud MK

See also

References

- 1 2 "List of localities, in Alphabetical order" (PDF). Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved August 26, 2018.

- ↑ Palmer, 1881, p. 108

- 1 2 Dan Savery Raz. "BBC - Travel - Israel's forgotten tribe".

- ↑ al-Qalqashandi version of the hudna, referred in Barag, 1979, p. 209, Nos. C1 and C2

- ↑ Guérin, 1865, pp. 296-296

- ↑ Conder and Kitchener, 1881, SWP I, p. 303

- ↑ Shadman, 2006, Horbat Devela, final report

- ↑ Golan, 2009, Horbat Devela, Final Report

- ↑ Naim Aridi (2009). The Druze in Israel. Univ.-Bibliotek Frankfurt am Main.

- 1 2 Conder and Kitchener, 1881, SWP I, p. 281

- ↑ Guérin, 1875, p.248

- ↑ Schumacher, 1888, p. 178

- ↑ Barron, 1923, Table XI, Sub-district of Haifa, p. 33

- ↑ Mills, 1932, p. 89

- 1 2 Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 47

- ↑ Department of Statistics, 1945, p. 13

- ↑ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 89

- ↑ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 139

- ↑ State of Israel, Government Year-Book 5713 (1952), page V.

- ↑ "Daliyat el-Karmel". Ministry of Tourism, State of Israel. Retrieved 2008-08-01.

- 1 2 "The town at the heart of Druze culture". Israel21c.

- ↑ "El Al honors Druze community". ynet.

- ↑ "Streetwise: Rehov Oliphant, Haifa". The Jerusalem Post - JPost.com.

- ↑ Inauguration of the Garden of the Mothers Archived 2013-09-27 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Freddie Krivine Tennis Schools Archived April 27, 2014, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Mevo Carmel". The Center for Jewish - Arab Economic Development. Archived from the original on 1 August 2014. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on October 6, 2014. Retrieved April 27, 2014.

- ↑ "Ambasada Republicii Moldova în Statul Israel".

Bibliography

- Barag, Dan (1979). "A new source concerning the ultimate borders of the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem". Israel Exploration Journal. 29: 197–217.

- Barron, J.B., ed. (1923). Palestine: Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1922. Government of Palestine.

- Conder, C.R.; Kitchener, H.H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. 1. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Department of Statistics (1945). Village Statistics, April, 1945. Government of Palestine.

- Golan, Sigal (2009-06-07). "Horbat Devela, Final Report" (121). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel.

- Guérin, V. (1875). Description Géographique Historique et Archéologique de la Palestine (in French). 2: Samarie, pt. 2. Paris: L'Imprimerie Nationale.

- Hadawi, S. (1970). Village Statistics of 1945: A Classification of Land and Area ownership in Palestine. Palestine Liberation Organization Research Center.

- Mills, E., ed. (1932). Census of Palestine 1931. Population of Villages, Towns and Administrative Areas. Jerusalem: Government of Palestine.

- Mülinen, Egbert Friedrich von 1908, Beiträge zur Kenntnis des Karmels "Separateabdruck aus der Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palëstina-Vereins Band XXX (1907) Seite 117-207 und Band XXXI (1908) Seite 1-258." ("Daliet el-kirmil": p. 242 ff. )

- Palmer, E.H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Arabic and English Name Lists Collected During the Survey by Lieutenants Conder and Kitchener, R. E. Transliterated and Explained by E.H. Palmer. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Schumacher, G. (1888). "Population list of the Liwa of Akka". Quarterly statement - Palestine Exploration Fund. 20: 169–191.

- Shadman, Amit (2006-07-02). "Horbat Devela, Final Report" (118). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel.

External links

- Welcome To Daliyat al-Carmel

- Israel tourist board: Daliyat al-Carmel

- Survey of Western Palestine, Map 5: IAA, Wikimedia commons