Cupressus macrocarpa

| Monterey cypress | |

|---|---|

| |

| The "Lone Cypress" near Monterey, California | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Pinophyta |

| Class: | Pinopsida |

| Order: | Pinales |

| Family: | Cupressaceae |

| Genus: | Cupressus |

| Species: | C. macrocarpa |

| Binomial name | |

| Cupressus macrocarpa Hartw. 1847 | |

| |

| |

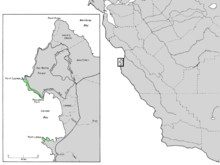

| Natural range in California | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Cupressus macrocarpa, (now classed as Hesperocyparis macrocarpa),[2] commonly known as Monterey cypress, is a species of cypress native to the Central Coast of California. The native range of the species was confined to two small relict populations, at Cypress Point in Pebble Beach and at Point Lobos near Carmel, California.[3]

Description

Cupressus macrocarpa is a medium-sized coniferous evergreen tree, which often becomes irregular and flat-topped as a result of the strong winds that are typical of its native area. It grows to heights of up to 40 meters (133 feet) in perfect growing conditions, and its trunk diameter can reach 2.5 meters (over 8 feet). The foliage grows in dense sprays which are bright green in color and release a deep lemony aroma when crushed. The leaves are scale-like, 2–5 mm long, and produced on rounded (not flattened) shoots; seedlings up to a year old have needle-like leaves 4–8 mm long.

The seed cones are globose to oblong, 20–40 mm long, with 6–14 scales, green at first, maturing brown about 20–24 months after pollination. The pollen cones are 3–5 mm long, and release their pollen in late winter or early spring.[4][5][6] The Latin specific epithet macrocarpa means "with large fruit".[7]

It has been widely reported that individual C. macrocarpa trees may be up to 2,000 years old, but this is disputed by botanists, and the longest-lived report based on physical evidence is of a tree 284 years old.[8] The renowned Californian botanist Willis Linn Jepson wrote that "the advertisement of [C. macrocarpa trees] in seaside literature as 1,000 to 2,000 years old does not ... rest upon any actual data, and probably represents a desire to minister to a popular craving for superlatives".[9]

Along with other New World Cupressus species, it has recently been transferred to the genus Hesperocyparis, on genetic evidence that the New World Cupressus are not very closely related to the Old World Cupressus species.[10][11]

Distribution

The two native cypress forest stands are protected, within Point Lobos State Reserve and Del Monte Forest. The natural habitat is noted for its cool, moist summers, almost constantly bathed by sea fog.[4][5]

This species has been widely planted outside its native range, particularly along the coasts of California and Oregon. Its European distribution includes Great Britain (including the Isle of Man and the Channel Islands), France, Ireland, Greece, Italy, Portugal, and Sicily.[12] In New Zealand, plantings have naturalized, finding conditions there more favorable than in its native range. It has also been grown experimentally as a timber crop in Kenya.[4][6]

Cupressus macrocarpa is also grown in South Africa. For example, a copse has been planted to commemorate South African infantry men who lost their lives in the Allied cause in Italy and North Africa during WW2. As in California, the Cape trees are gnarled and wind-sculpted, and very beautiful.

Cultivation

Monterey cypress has been widely cultivated away from its native range, both elsewhere along the California coast, and in other areas with similar cool summer, mild winter oceanic climates. It is a popular private garden and public landscape tree in California.

When planted in areas with hot summers, for example in interior California away from the coastal fog belt, Monterey cypress has proved highly susceptible to cypress canker, caused by the fungus Seiridium cardinale, and rarely survives more than a few years. This disease is not a problem where summers are cool.[13]

A number of cultivars have been selected for garden use, including 'Goldcrest', with yellow-green, semi-juvenile foliage (with spreading scale-leaf tips) and 'Lutea' with yellow-green foliage. 'Goldcrest' has gained the Royal Horticultural Society's Award of Garden Merit[14] (confirmed 2017).[15]

Monterey cypress is one of the parents of the fast-growing cultivated hybrid Leyland cypress, Cupressus × Leylandii, the other parent being Nootka cypress, Cupressus nootkatensis.[6]

The foliage is slightly toxic to livestock and can cause miscarriages in cattle.[16] Sawn logs are used by many craftspeople, some boat builders and small manufacturers, as a furniture structural material and a decorative wood because of its fine colours. It is also a fast, hot burning, albeit sparky (therefore not suited to open fires), firewood.

In Australia and New Zealand, Monterey cypress is most frequently grown as a windbreak tree on farms, usually in rows or shelter belts. It is also planted in New Zealand as an ornamental tree and, occasionally, as a timber tree. There, finding more favorable growing conditions than in its native range, and in the absence of many native pathogens, it often grows much larger, with trees recorded at over 40 m (130 ft) tall and 3 m (9.8 ft) in trunk diameter.[4][6] (One specimen - with a trunk diameter of more than 4.6 m (15 ft) - is considered to be perhaps the largest in the world.)[17] The timber of Monterey cypress was used for fence posts on New Zealand farms before electric fencing became popular.

Macrocarpa cultivars grown in New Zealand are:[18]

- 'Aurea Saligna'—long cascades of weeping, golden-yellow, thread-like foliage on a pyramidal tree

- 'Brunniana Aurea'—pillar or conical form with soft rich-golden foliage

- 'Gold Rocket'—narrow erect form with golden colouring, slow-growing

- 'Golden Pillar'—compact conical tree with dense yellow shoots and foliage

- 'Greenstead Magnificent'—dwarf form with blue-green foliage

- 'Lambertiana Aurea'—hardy upright form tolerating poor soil and climate conditions

Seedling showing needle-like juvenile leaves |

'Goldcrest' |

Semi-juvenile foliage of cultivar 'Goldcrest' |

Chemistry

Isocupressic acid, a labdane diterpenoid, is an abortifacient component of C. macrocarpa.[19] Monoterpenes (α- and γ-terpinene and terpinolene) are constituents of the foliage volatile oil.[20] The oil exact composition is : α-pinene (20.2%), sabinene (12.0%), p-cymene (7.0%) and terpinen-4-ol (29.6%).[21] Unusual sesquiterpenes can be found in the foliage.[22] Longiborneol (also known as juniperol or macrocarpol) can also be isolated from Monterey cypresses.[23]

References

- ↑ Farjon, A. (2013). "Cupressus macrocarpa". The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (2013). doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2013-1.RLTS.T30375A2793139.en.

- ↑ http://calscape.org/Hesperocyparis-macrocarpa-()

- ↑ C. Michael Hogan & Michael P. Frankis. 2009. Monterey Cypress: Cupressus macrocarpa, GlobalTwitcher.com ed. N. Stromberg

- 1 2 3 4 Farjon, A. (2005). Monograph of Cupressaceae and Sciadopitys. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. ISBN 1-84246-068-4

- 1 2 Eckenwalder, James E. (1993). "Cupressus macrocarpa". In Flora of North America Editorial Committee. Flora of North America North of Mexico (FNA). 2. New York and Oxford – via eFloras.org, Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis, MO & Harvard University Herbaria, Cambridge, MA.

- 1 2 3 4 K. Rushforth (1987). Conifers. Helm. ISBN 0-7470-2801-X.

- ↑ Harrison, Lorraine (2012). RHS Latin for Gardeners. United Kingdom: Mitchell Beazley. ISBN 184533731X.

- ↑ Willis Linn Jepson (1923). The Trees of California (2nd ed.). University of California Press. p. 75.

- ↑ Willis Linn Jepson (1919). "Appendix I: scientific notes on the Monterey cypress". In Joseph H. Engbeck. Point Lobos Reserve State Park, California: Interpretation of a Primitive Landscape. University of California. pp. 86–87.

- ↑ Damon P. Little (2006). "Evolution and circumscription of the true cypresses (Cupressaceae: Cupressus)". Systematic Botany. 31 (3): 461–480. doi:10.1600/036364406778388638. JSTOR 25064176.

- ↑ Robert P. Adams; Jim A. Bartel; Robert A. Price (2009). "A new genus, Hesperocyparis, for the cypresses of the Western Hemisphere" (PDF). Phytologia. 91 (1): 160–185.

- ↑ "Cupressus macrocarpa". Flora Europaea. Edinburgh: Royal Botanical Garden. 2008.

- ↑ W. W. Wagener (1948). "Diseases of Cypresses". El Aliso. 1: 253–321.

- ↑ "Cupressus macropcarpa 'Goldcrest'". Royal Horticultural Society. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- ↑ "AGM Plants - Ornamental" (PDF). Royal Horticultural Society. July 2017. p. 22. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ↑ V. Sloss; J. W. Brady (1983). "Abnormal births in cattle following ingestion of Cupressus macrocarpa foliage". Australian Veterinary Journal. 60 (7): 223. doi:10.1111/j.1751-0813.1983.tb09593.x. PMID 6639522.

- ↑ "The New Zealand Tree Register".

- ↑ Staney J. Palmer (1990). Palmer's Manual of Trees, Shrubs and Climbers. Lancewood Publishing. ISBN 0-7316-9415-5.

- ↑ K. Parton; D. Gardner; N. B. Williamson (1996). "Isocupressic acid, an abortifacient component of Cupressus macrocarpa". New Zealand Veterinary Journal. 44 (3). doi:10.1080/00480169.1996.35946.

- ↑ Eugene Zavarin; Lorraine Lawrence; Mary C. Thomas (1971). "Compositional variations of leaf monoterpenes in Cupressus macrocarpa, C. pygmaea, C. goveniana, C. abramsiana and C. sargentii". Phytochemistry. 10 (2): 379–393. doi:10.1016/S0031-9422(00)94053-6.

- ↑ Rubén A. Malizia; Daniel A. Cardell; José S. Molli; Silvia González; Pedro E. Guerra; Ricardo J. Grau (2000). "Volatile constituents of leaf oils from the Cupressaceae family: Part I. Cupressus macrocarpa Hartw., C. arizonica Greene and C. torulosa Don species growing in Argentina". Journal of Essential Oil Research. 12 (1): 59–63. doi:10.1080/10412905.2000.9712042.

- ↑ Laurence G. Cool (2005). "Sesquiterpenes from Cupressus macrocarpa foliage". Phytochemistry. 66 (2): 249–260. doi:10.1016/j.phytochem.2004.11.002.

- ↑ Steven C. Welch; Roland L. Walters (1973). "Total syntheses of (+)-longicamphor and (+)-longiborneol". Synthetic Communications. 3 (6): 419–423. doi:10.1080/00397917308065935.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cupressus macrocarpa. |