Cordon sanitaire

| Look up cordon sanitaire in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

Cordon sanitaire (French pronunciation: [kɔʁdɔ̃ sanitɛʁ]) is a French phrase that, literally translated, means "sanitary cordon". It originally denoted a barrier implemented to stop the spread of infectious diseases. It may be used interchangeably with the term "quarantine", and although the terms are related, cordon sanitaire refers to the restriction of movement of people within a defined geographic area, such as a community.[1] The term is also often used metaphorically, in English, to refer to attempts to prevent the spread of an ideology deemed unwanted or dangerous,[2] such as the containment policy adopted by George F. Kennan against the Soviet Union.

For disease

A cordon sanitaire is generally created around an area experiencing an epidemic or an outbreak of infectious disease, or along the border between two nations. Once the cordon is established, people from the affected area are no longer allowed to leave or enter it. In the most extreme form, the cordon is not lifted until the infection is extinguished.[3] Traditionally, the line around a cordon sanitaire was quite physical; a fence or wall was built, armed troops patrolled, and inside, inhabitants were left to battle the affliction without help. In some cases, a "reverse cordon sanitaire" (also known as protective sequestration) may be imposed on healthy communities that are attempting to keep an infection from being introduced. Public health specialists have included cordon sanitaire along with quarantine and medical isolation as "nonpharmaceutical interventions" designed to prevent the transmission of microbial pathogens through social distancing.[4]

The cordon sanitaire is rarely used now because of our improved understanding of disease transmission, treatment and prevention. It remains a useful intervention under conditions in which: 1) the infection is highly virulent (contagious and likely to cause illness); 2) the case fatality rate is very high; 3) treatment is nonexistent or difficult; and 4) there is no vaccine or other means of immunizing large numbers of people.[5]

Historical examples

- In May 1666, the English village of Eyam famously imposed a cordon sanitaire on itself after an outbreak of the bubonic plague in the community. During the next 14 months almost eighty percent of the inhabitants died.[6] A perimeter of stones was laid out surrounding the village and no one passed the boundary in either direction until November, when the pestilence had run its course. Neighboring communities provided food for Eyam, leaving supplies in designated locations along the boundary cordon and receiving payment in coins "disinfected" by running water or vinegar.[7]

- During the Great Northern War plague outbreak of 1708-1712, cordons sanitaires were established around affected towns like Stralsund and Königsberg; one was also established around the whole Duchy of Prussia and another one between Scania and the Danish isles along the Sound, with Saltholm as the central quarantine station.[8]

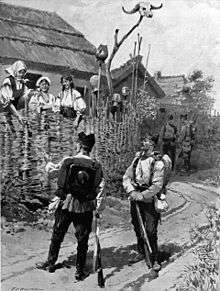

- In 1770 the Empress Maria Theresa set up a cordon sanitaire between Austria and the Ottoman Empire to prevent people and goods infected with plague from crossing the border. Cotton and wool were held in storehouses for weeks, with peasants paid to sleep on the bales and monitored to see if they showed signs of disease. Travelers were quarantined for 21 days under ordinary circumstances and up to 48 days when there was confirmation of plague being active in Ottoman territory. The cordon was maintained until 1871, and there were no major outbreaks of plague in Austrian territory after the cordon sanitaire was established, whereas the Ottoman Empire continued to suffer frequent epidemics of plague until the mid-nineteenth century.[7]

- During the 1793 Philadelphia yellow fever epidemic, roads and bridges leading to the city were blocked off by soldiers from the local militia to prevent the illness from spreading. This was before the transmission mechanics of yellow fever were well understood.[9][10]

- The first actual use of the term cordon sanitaire was in 1821, when the Duke de Richelieu deployed 30,000 French troops to the border between France and Spain in the Pyrenees Mountains, in order to prevent yellow fever from spreading from Spain into France.[11]

- The 1821 yellow fever epidemic ravaged Barcelona and a cordon sanitaire was set up around the entire city of 150,000 people. Between 18,000 and 20,000 died in four months.[7]

- During the 1830 cholera outbreak in Russia, Moscow was surrounded by a military cordon, most roads leading to the city were dug up to hinder travel, and all but four entrances to the city were sealed.[7]

- During the 1856 yellow fever epidemic a cordon sanitaire was implemented in several cities in the state of Georgia with moderate success.[12]

- In 1869, Adrien Proust (father of novelist Marcel Proust) proposed the use of an international cordon sanitaire to control the spread of cholera, which had emerged from India and was threatening Europe and Africa. Proust proposed that all ships bound for Europe from India and Southeast Asia be quarantined at Suez, however his ideas were not generally embraced.[13][14]

- In 1882, in response to a virulent outbreak of yellow fever in Brownsville, Texas and in northern Mexico, a cordon sanitaire was established 180 miles north of the city, terminating at the Rio Grande to the west and the Gulf of Mexico to the east. People traveling north had to remain quarantined at the cordon for 10 days before they were certified disease-free and could proceed.[7]

- In 1888, during a yellow fever epidemic, the city of Jacksonville, Florida was surrounded by an armed cordon sanitaire by order of Governor Edward A. Perry.[15]

- In 1899 an outbreak of the plague in Honolulu was managed by a cordon sanitaire around the Chinatown district. In an attempt to control the infection, a barbed wire perimeter was created and people's belongings and homes were burned.[16]

- During the San Francisco plague of 1900–1904 San Francisco's Chinatown was subjected to a cordon sanitaire.[17]

- In 1902, Louisiana imposed a cordon sanitaire to prevent Italian immigrants from disembarking at the port of New Orleans. The shipping company sued for damages, but the state's right to impose a cordon was upheld in Compagnie Francaise de Navigation a Vapeur v. Louisiana Board of Health.

- From 1903 to 1914, the Belgian colonial government imposed a cordon sanitaire on Uele Province in the Belgian Congo to control outbreaks of trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness).[18]

- The 1918 flu pandemic spread so rapidly that, in general, there was no time to implement cordons sanitaires. However, to prevent an introduction of the infection, residents of Gunnison, Colorado isolated themselves from the surrounding area for two months at the end of 1918. All highways were barricaded near the county lines. Train conductors warned all passengers that if they stepped outside of the train in Gunnison, they would be arrested and quarantined for five days. As a result of this protective sequestration, no one died of influenza in Gunnison during the epidemic.[19]

- In late 1918, Spain attempted unsuccessfully to prevent the spread of the Spanish flu by imposing border controls, roadblocks, restricted rail travel, and a maritime cordon sanitaire prohibiting ships with sick passengers from landing, but by then the epidemic was already in progress.[20]

- During the 1972 Yugoslav smallpox outbreak, over 10,000 people were sequestered in cordons sanitaires of villages and neighborhoods using roadblocks, and there was a general prohibition of public meetings, a closure of all borders and a prohibition of all non-essential travel.

- In 1995 a cordon sanitaire was used to control an outbreak of Ebola virus disease in Kikwit, Zaire.[21][22][5] President Mobutu Sese Seko surrounded the town with troops and suspended all flights into the community. Inside Kikwit, the World Health Organization and Zaire medical teams erected further cordons sanitaires, isolating burial and treatment zones from the general population.[23]

- During the 2003 SARS outbreak in Canada, "community quarantine" was used to successfully reduce transmission of the disease.[24]

- During the 2003 SARS outbreak in mainland China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Singapore, large-scale quarantine was imposed on travelers arriving from other SARS areas, work and school contacts of suspected cases, and, in a few instances, entire apartment complexes where high attack rates of SARS were occurring.[25] In China, entire villages in rural areas were quarantined and no travel was allowed in or out of the villages. One village in Hebei Province was quarantined from April 12, 2003 until May 13. Tens of thousands of individuals fled from areas when they learned of an impending cordon sanitaire, thereby possibly spreading the epidemic.[26]

- In August 2014 a cordon sanitaire was established around some of the most affected areas of the 2014 West Africa Ebola virus outbreak.[27][28] On 19 August, the Liberian government quarantined the entirety of West Point, Monrovia and issued a curfew statewide.[29][30] The cordon sanitaire of the West Point area was lifted on 30 August. The Information Minister, Lewis Brown, said that this step was taken to ease efforts to screen, test, and treat residents.[31]

In popular culture

- A cordon sanitaire was used as a plot device by Albert Camus in his 1947 novel The Plague.

- In the 1995 film Outbreak, an Ebola-like virus brought from Africa causes an epidemic in a small town in California, resulting in the United States Army forming a cordon sanitaire around the town.

- The 2002 film 28 Days Later depicts a cordon sanitaire imposed on Great Britain as a viral infection devastates the population.

- In The Last Town on Earth, a 2006 novel by Thomas Mullen, the town of Commonwealth, Washington in 1918 imposes a reverse cordon sanitaire to avoid the Spanish Flu, however the disease is introduced by a wandering soldier.

- In the 2006 novel World War Z the nation of Israel imposes a reverse cordon sanitaire to keep zombies out.

- In the 2011 film Contagion, the city of Chicago is cordoned off to contain the spread of a meningoencephalitis virus.

- In the 2014 Belgian TV series Cordon a cordon sanitaire is set up to contain an outbreak of Avian flu in Antwerp.

- In the 2016 television limited series Containment a cordon sanitaire is set up to contain an infectious virus in Atlanta, Georgia.

In diplomacy

The seminal use of "cordon sanitaire" as a metaphor for ideological containment referred to "the system of alliances instituted by France in post-World War I Europe that stretched from Finland to the Balkans" and which "completely ringed Germany and sealed off Russia from Western Europe, thereby isolating the two politically 'diseased' nations of Europe."[32]

French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau is credited with coining the usage, when in March 1919 he urged the newly independent border states (also called limitrophe states) that had seceded from the Russian Empire and its successor the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics to form a defensive union and thus quarantine the spread of communism to Western Europe; he called such an alliance a cordon sanitaire. This is still probably the most famous use of the phrase, though it is sometimes used more generally to describe a set of buffer states that form a barrier against a larger, ideologically hostile state.

In politics

Beginning in the late 1980s, the term was introduced into the discourse on parliamentary politics by Belgian commentators. At that time, the far-right Flemish nationalist Vlaams Blok party began to make significant electoral gains. Because the Vlaams Blok was considered a racist group by many, the other Belgian political parties committed to exclude the party from any coalition government, even if that forced the formation of grand coalition governments between ideological rivals. Commentators dubbed this agreement Belgium's cordon sanitaire. In 2004, its successor party, Vlaams Belang changed its party platform to allow it to comply with the law. While no formal new agreement has been signed against it, it nevertheless remains uncertain whether any mainstream Belgian party will enter into coalition talks with Vlaams Belang in the near future. Several members of various Flemish parties have questioned the viability of the cordon sanitaire. Critics of the cordon sanitaire claim that it is also undemocratic.

With the electoral success of nationalist and extremist parties on the left and right in recent European history, the term has been transferred to agreements similar to the one struck in Belgium:

- In Italy, the Italian Communist Party and Italian Social Movement were excluded from Christian democrats-led coalition governments during the Cold War. The end of the Cold War along with the Tangentopoli scandal and Mani pulite investigation resulted in a dramatic political realignment.

- After German reunification, East Germany's former ruling party, the Socialist Unity Party of Germany (Sozialistische Einheitspartei Deutschlands, or SED), reinvented itself first (in 1990) as the Party of Democratic Socialism (PDS) and then (in 2005 before the elections) as the Left Party, in order to merge with the new group WASG that had emerged in the West. In the years following 1990, the other German political parties have consistently refused to consider forming a coalition with the PDS/Left Party on a federal level (which was possible in 2005 and 2013), while on state levels, so-called red-red coalitions with the SPD were formed (or red-red-green). The term cordon sanitaire, though, is quite uncommon in Germany for coalition considerations. A strict political non-cooperation (in which The Left would participate, should the instance ever arise) is only exercised against right-wing parties, such as the Republicans, and even the Republicans have exercised a cordon against the neo-Nazi National Democrats. Since 2013, the established major parties have refused to form state-level coalitions with the new right-wing populist party AfD.

- In the Netherlands, a parliamentary cordon sanitaire was put around the Centre Party (Centrumpartij, CP) and later on the Centre Democrats (Centrumdemocraten, CD), ostracising their leader Hans Janmaat. During the 2010 Cabinet formation, Geert Wilders' Party for Freedom (Partij voor de Vrijheid, PVV) charged other parties of plotting a cordon sanitaire; however, there never was any agreement between the other parties on ignoring the PVV. Indeed, the PVV was floated several times as a potential coalition member by several informateurs throughout the government formation process, and the final minority coalition under Mark Rutte between Rutte's People's Party for Freedom and Democracy and the Christian Democratic Appeal was officially "condoned" by the PVV. The coalition collapsed after PVV withdrew its support in 2012. Since then, all major parties refuse to cooperate with PVV.

- Some (though not all) of the Non-Inscrits members of the European Parliament are unaffiliated because they are considered to lie too far on the right of the political spectrum to be acceptable to any of the European Parliament party groups.

- In France, the policy of non-cooperation with Front National, together with the majoritarian two-round electoral system, leads to the permanent underrepresentation of the FN in the National Assembly. For instance, the FN won no seats out of 577 in the 2002 elections, despite receiving 11.3% of votes in the first round, as no FN candidates won a first-round majority and few even qualified (either by winning at least 12.5% of the local vote with 25% turnout or by being one of the top two finishers with less) to go on to the second round. In the 2002 presidential election, after the Front National candidate Jean-Marie Le Pen unexpectedly defeated Lionel Jospin in the first round, the traditionally ideologically-opposed Socialist Party encouraged its voters to vote for Jacques Chirac in the second round, preferring anyone to Le Pen.

- In the Czech Republic, the Communist Party is effectively excluded from any possible coalition because of a strong anti-Communist presence in most political parties, including the Social Democrats. Also a cordon sanitaire was put around the Republicans of Miroslav Sládek, when they were active in the Parliament (1992–1998). When any of its members was set to speak, other deputies would leave the Chamber of Deputies.

- In Estonia and Latvia, "Russian-speaking" parties (LKS and Harmony in Latvia, and the Constitution Party and Centre Party in Estonia) had been excluded from participation in ruling coalitions at a national level until leadership change. Differing interpretations of the Soviet period from 1940-1990 and attitudes towards the current Russian government and United Russia are often cited as reasons to conclude coalition talks with other parties, even if said parties are perceived to be on the radical right. The cordon is not absolute; the Centre Party has briefly participated in two coalition governments in 1995 and 2002-2003. In 2016 Jüri Ratas of Centre became Prime Minister of Estonia, effectively ending any cordon around the party.

- In Spain, groups such as the People's Party, have been sometimes excluded from any government coalition in Catalonia.[33]

- In Sweden, the political parties in the Riksdag have adopted a policy of non-cooperation with the Sweden Democrats. However, there have been exceptions where local politicians have supported resolutions from SD.

- In Norway, all the parliamentary parties had consistently refused to formally join into a governing coalition at state level with the right-wing Progress Party until 2005 when the Conservative Party did so. In some municipalities however, the Progress Party cooperates with many parties, including the center-left Labour Party.[34]

- In Canada, resistance to the formation of coalition governments among left-of-center parties has often been attributed to an unwillingness to be seen as collaborating with the Bloc Québécois, which advocates for the independence of Quebec.

- In the United Kingdom, the far-right British National Party is completely ostracised by the political mainstream. Prominent politicians, including former Prime Minister and Conservative Party leader David Cameron, have been known to urge electors to vote for candidates from any party except the BNP.[35] The eurosceptic United Kingdom Independence Party has categorically refused even limited cooperation with the BNP.[36] Although the party has never held more than 60 of the some 22,000 elected positions in local government, it is generally agreed by all parties that the BNP should be excluded from any coalition agreement on those councils where no single party has a majority. When two BNP candidates were elected to the European Parliament at the 2009 election, the UK Government announced that it would provide them both with only the bare minimum level of support, denying them the ready access to officials and information that the other 70 British MEPs received.[37]

See also

References

- ↑ Rothstein, Mark A. "From SARS to Ebola: legal and ethical considerations for modern quarantine." Ind. Health L. Rev. 12 (2015): 227.

- ↑ Harold H. Fisher, Famine in Soviet Russia, Macmillan: New York, 1927; p. 25

- ↑ McNeil, Donald G. "Using a Tactic Unseen in a Century, Countries Cordon Off Ebola-Racked Areas". www.nytimes.com. New York Times. Retrieved 14 August 2014.

- ↑ Markel, Howard; et al. (2007). "Nonpharmaceutical interventions implemented by US cities during the 1918-1919 influenza pandemic". JAMA. 298 (6): 644–654. doi:10.1001/jama.298.6.644.

- 1 2 Rachel Kaplan Hoffmann and Keith Hoffmann, "Ethical Considerations in the Use of Cordons Sanitaires," Clinical Correlations, February 19, 2015.

- ↑ Philip Race, "The Plague in Eyam, 1665-66."

- 1 2 3 4 5 George C. Kohn, Encyclopedia of Plague and Pestilence: From Ancient Times to the Present, Infobase Publishing, 2007; p. 30. ISBN 1438129238

- ↑ Karl-Erik Frandsen, The Last Plague in the Baltic Region, 1709-1713. Museum Tusculanum Press, 2010. ISBN 8763507706

- ↑ Powell J. H., Bring Out Your Dead: The Great Plague of Yellow Fever in Philadelphia in 1793, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2014.

- ↑ Arnebeck, Bob. "A Short History of Yellow Fever in the US". January 30, 2008; From Benjamin Rush, Yellow Fever and the Birth of Modern Medicine.

- ↑ James Taylor, The age we live in: a history of the nineteenth century, Oxford University, 1882; p. 222.

- ↑ Campbell, HF (1879). "The Yellow Fever Quarantine of the Future, as Organized upon the Portability of Atmospheric Germs and upon the Non-Contagiousness of the Disease". Public Health Pap Rep. 5: 131–44. PMC 2272165. PMID 19600008.

- ↑ William C. Carter, Marcel Proust: A Life, Yale University Press, 2002; pp. 10-11. ISBN 0300094000

- ↑ Weissmann, Gerald. "Ebola, Dynamin, and the Cordon Sanitaire of Dr. Adrien Proust." Journal of the Society for Experiemental Biology, vol. 29 no. 1, Jan 2015: 1-4.

- ↑ Florida Memory: Epidemic Disease and the Establishment of the Board of Health State Archives of Florida

- ↑ The Disastrous Cordon Sanitaire Used on Honolulu's Chinatown in 1900

- ↑ Mark Skubik, "Public Health Politics and the San Francisco Plague Epidemic of 1900-1904," Doctoral Thesis, San Jose State University, 2002

- ↑ Maryinez Lyons, "From 'Death Camps' to Cordon Sanitaire: The Development of Sleeping Sickness Policy in the Uele District of the Belgian Congo, 1903-1914," The Journal of African History, Vol. 26, No. 1 (1985), pp. 69-91 Cambridge University Press

- ↑ Gunnison: Case Study, University of Michigan Medical School, Center for the History of Medicine

- ↑ R. Davis, The Spanish Flu: Narrative and Cultural Identity in Spain, 1918, Springer, 2013. ISBN 1137339217

- ↑ Laurie Garrett, "Heartless but Effective: I've Seen 'Cordon Sanitaire' Work Against Ebola," The New Republic, August 14, 2014

- ↑ "Outbreak of Ebola Viral Hemorrhagic Fever -- Zaire, 1995" Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, May 19, 1995 / 44(19);381-382

- ↑ Laurie Garrett, Betrayal of Trust: The Collapse of Global Public Health, Hachette Books, 2011 ISBN 1401303862

- ↑ Bondy, SJ; Russell, ML; Laflèche, JM; Rea, E (2009). "Quantifying the impact of community quarantine on SARS transmission in Ontario: estimation of secondary case count difference and number needed to quarantine". BMC Public Health. 9: 488. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-9-488. PMC 2808319. PMID 20034405.

- ↑ Martin Cetron, et al. "Isolation and Quarantine: Containment Strategies for SARS, 2003." From Learning from SARS: Preparing for the Next Disease Outbreak, National Academy of Sciences, 2004. ISBN 0309594332

- ↑ Center for Disease Control, et al. "Quarantine and Isolation: Lessons learned from SARS." University of Louisville School of Medicine, Institute for Bioethics, Health Policy and Law, 2003.

- ↑ "Community Quarantine to Interrupt Ebola Virus Transmission — Mawah Village, Bong County, Liberia, August–October, 2014," Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, February 27, 2015 / 64(07);179-182.

- ↑ Donald G. McNeil Jr. (August 13, 2014). "Using a Tactic Unseen in a Century, Countries Cordon Off Ebola-Racked Areas". www.nytimes.com. The New York Times.

- ↑ "Liberian Soldiers Seal Slum to Halt Ebola". NBC News. 2014-08-09. Retrieved 2014-08-23.

- ↑ Clair MacDougall; James Harding Giahyue (2014-08-20). "Liberia police fire on protesters as West Africa's Ebola toll hits 1,350". Reuters. Retrieved 2014-08-23.

- ↑ "Liberian Ebola survivor calls for quick production of experimental drug". Global News. 30 August 2014. Retrieved 30 August 2014.

- ↑ Gilchrist, Stanley (1995) [1st. pub. 1982]. "Chapter 10: The Cordon Sanitaire - Is It Useful? Is It Practical?". In Moore, John Norton; Turner, Robert F. Readings on International Law from the Naval War College Review, 1978-1994. 68. Naval War College. pp. 131–145.

- ↑ "Criterios sobre actuación política general" [General Policy on Performance Criteria] (PDF) (in Spanish). Multimedia Capital. Retrieved 4 April 2015.

- ↑ "- Nulltoleranse mot Frp-samarbeid", Arbeiderpartiet Archived 2012-07-01 at Archive.is

- ↑ "Guardian: Cameron: vote for anyone but BNP". The Guardian. London. 18 April 2006. Retrieved 26 March 2010.

- ↑ BBC News (3 November 2008). "UKIP rejects BNP electoral offer". Retrieved 19 November 2011.

- ↑ Traynor, Ian (9 July 2009). "UK diplomats shun BNP officials in Europe". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 23 October 2009.