Cocoliztli Epidemic of 1545–1548

Between 1545-1548 A.D., a mysterious illness, which was characterized by high fevers and bleeding, ravished the Mexican highlands in epidemic proportions. The disease became known as Cocoliztli by the native Aztecs, and had devastating effects on the area’s demography, particularly for the indigenous people. Based on the death toll, this outbreak is often referred to as the worst disease epidemic in the history of Mexico[1][2][3] Subsequent outbreaks continued to baffle both Spanish and native doctors, with little consensus among modern researchers on the pathogenesis. However, recent bacterial genomic studies have suggested that Salmonella, specifically a serotype of Salmonella enterica known as Paratyphi C, was at least partially responsible for this initial outbreak[4].

Symptoms

Although symptomatic descriptions of cocoliztli are similar to those of Old World diseases (e.g. measles, yellow fever, typhus), many researchers believe that it should be recognized as a separate malady[1][2][4][5][6]. Colonial accounts detailing the Outbreak of 1545-1548 indicate that nose bleeding, jaundice, and severe fevers were the most frequently reported symptoms[1][2]. Some also describe the afflicted during this period as having spotted skin[7] and internal bleeding (gastrointestinal hemorrhaging), leading to bloody diarrhea, as well as, bleeding from the eyes, mouth, and vagina[5][6]. The onset was often rapid, and without any precursors that would suggest one is sick[2]. The disease is characterized by an extremely high level of virulence, with death often occurring within a week of one becoming symptomatic[2]. Due to the virulence and effectiveness of the disease, recognizing its existence in the archaeological record has been difficult. Cocoliztli, and other diseases that work rapidly, usually do not leave impacts (lesions) on the deceased’s bones, despite causing significant damage to the gastrointestinal, respiratory, and other bodily systems[8].

Background

The Cocoliztli Epidemic of 1545 was first reported in August of that year, and was appeared to be different from other Old World Diseases, such as measles or smallpox[1] [9]. The outbreak is the deadliest of at least six cocoliztli epidemics that occurred in Central America during the 16th century[2]. The name, cocoliztli, is the Nahuatl word for “pestilence" (sometimes translated as ‘pest’ or ‘plague’)[5][9][10]. The Spanish, who at the time were as unfamiliar with it as the Aztecs were, termed the disease, “pujamiento de sangre” (full bloodiness)[1]. In later colonial documents, eyewitnesses refer to the sickness as “tabardillo,” which is the Spanish word for typhus[5]. The epidemic of 1545 followed ten years after the end of a massive measles outbreak between 1530-1534, and about 25 years after smallpox first reached Mexico[9]. The latter was concurrent with the Spanish’s efforts to conquer the Aztecs, which began in earnest with the arrival of Hernan Cortez in 1519. According to Bernal Diaz, a conquistador that accompanied Cortez, these earlier outbreaks were instrumental in the Spanish conquest of the Aztec empire[11].

It is not known where the epidemic started exactly, but scholars suspect it to have originally been concentrated in the southern and central Mexico Highlands, near modern-day Puebla City[1]. Shortly after its initial onset, however, it appears to have spread as far north as Sinaloa[9], and as south as Chiapas and Guatemala, where it was referred to as gucumatz[12]. It may have even crossed the South American border, and into Ecuador[13] and Peru[14], although it is hard to be certain that the same disease is being described. There was a tendency for the outbreak to be limited to areas of higher elevation, as it was nearly absent from coastal regions at sea-level, e.g. the plains along the Gulf of Mexico and Pacific coast[3].

There exists some ambiguity regarding if cocoliztli preferentially targeted native people, as opposed to European colonists. The majority of firsthand accounts regarding the outbreak come from Aztec informants, who were primarily concerned with the diseases’ novelty and pronounced symptoms. Spanish colonizers may have used indigenous fears to further justify and enforce Christianity, as expressed by the following statement from Gonzalo de Ortiz (an encomendero): “envió Dios tal enfermedad sobre ellos que de quarto partes de indios que avia se llevó las tres,” (God sent down such sickness upon the Indians that three out of every four of them perished)[12]. It is unclear if Ortiz was exaggerating, or if the Spanish colonizers were truly less affected by this “act of God.” Accounts by Toribio de Benavente Motolinia, an early Spanish missionary, seem to contradict Ortiz’s sentiment by suggesting that 60-90% of New Spain’s total population decreased, regardless of ethnicity[1]. Bernardino de Sahagún, another Spanish clergyman and author of the Florentine Codex, attested to contracting the disease himself towards the end of the outbreak[1]. During a second cocoliztli outbreak in 1576, Sahagún identified both African slaves and Spanish colonists as being susceptible to the disease.

Effects

Death toll

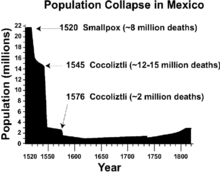

Beyond the estimations done by Motolinia and others for New Spain, most of the death toll figures cited for the outbreak of 1545-1548 are concerned with Aztec populations. At Aztec settlements, such as Tlaxcala and Cholula, daily death totals ranged from 400-1000 people[1]. Around 800,000 died in the Valley of Mexico[2], which led to the widespread abandonment of many indigenous sites in the area during, or, shortly after this four year period[7]. Estimates for the entire number of human lives lost during this epidemic have ranged from 5 to 15 million people[15], making it one of the most deadly disease outbreaks of all time. Several researchers have hypothesized that around 80% of Mexico’s native population (5.1 million people) died during the outbreak (based on an estimated, indigenous population of around 6.4 million people for Mexico in 1545)[3]. In some areas, death tolls reached up to 95% of the population[4], with the overall carnage resembling that of the Black Death, which claimed around half (25 million people) of Western Europe’s population between 1347-1351[3]. This epidemic was the largest loss of life in Colonial Mexico, and part of a series of reductions that resulted in the Aztec population falling from around 25-30 million in 1519, to less than 2 million by 1700[10].

Other

The effects of the outbreak extended beyond just a loss in terms of population. The lack of indigenous labor led to a sizeable food shortage, which affected both the natives and Spanish[16]. By 1545, the use of the encomienda system, in which the Spanish crown rewarded conquistadors with lands and the right extract labor from the native people, was rapidly declining in Mexico[17]. The death of many Aztecs at the hands of the plague led to a void in land ownership, with Spanish colonists of all backgrounds looking to exploit these now vacant lands[16]. Coincidentally, the Spanish Emperor, Charles V, had been seeking a way to disempower the encomendero class, and establish a more efficient and “ethical” settlement system[18].

Starting around the end of the outbreak in 1549, the encomederos, crippled by the loss in profits resulting and unable to meet the demands of New Spain, were forced to comply with the new tasaciones (regulations)[16]. The new ordinances, known as Leyes Nuevas aimed to limit the amount of tribute encomenderos could personally extract, while also prohibiting them from exercising absolute control over the labor force[19]. Simultaneously, non-encomenderos began claiming lands lost by the encomenderos, as well as, the labor provided by the indigenous. This developed in to the implementation of the repartimiento system, which sought to institute a higher level of oversight within the Spanish colonies and maximize the overall tribute extracted for public and crown use[16]. Rules regarding tribute itself were also changed in response to the epidemic of 1545, as fears over future food shortages ran rampant among the Spanish. By 1577, after years of debate and a second major outbreak of cocoliztli, maize and money were designated as the only two forms of acceptable tribute[7][16].

Causes

Previous explanations

Numerous 16th century accounts detail the outbreak’s devastation, yet the causal agent has remained elusive from researchers interested in uncovering the roots of this epidemic. Shortly after 1548, the Spanish started calling the disease tabardillo (typhus), which had only been recognized in Spain since the late 15th century[9]. However, the symptoms of cocoliztli were still not identical to the typhus, or spotted fever, observed in the Old World at that time. Perhaps, this is why Francisco Hernández de Toledo, a Spanish physician, insisted on using the Nahuatl word when describing the disease to correspondents in the Old World[5]. Centuries later, in 1970, a historian named Germain Somolinos d'Ardois took a systematic look at all the proposed explanations at the time, including haemorrhagic influenza, leptospirosis, malaria, typhus, typhoid and yellow fever.[6] According to Somolinos d'Ardois, none of these quite matched the 16th century accounts of cocoliztli, leading him to conclude the disease was a result of “viral process of hemorrhagic influence.” In other words, Somolinos d'Ardois believed cocoliztli was not the result of any known Old World pathogen, but possibly, a virus of either European or New World origins.

Marr and Kiracofe (2000) attempted to build off this work by reexamining Hernandez’s account of cocoliztli and comparing them with various clinical descriptions of other diseases[5]. They suggested that scholars consider “New World arenaviruses” and the role these pathogens may have played in colonial disease outbreaks. Rebelling against the universal acceptance of Post-Contact epidemics being “Old-World importations,” Marr and Kiracofe theorized that arenaviruses, which mainly affect rodents[20], were largely kept away from Pre-Columbian people. Consequently, rat and mice infestations brought upon by the arrival of the Spanish may, combined with climatic and landscape change, may have brought these arenaviruses into much closer contact with people. Subsequent studies seemed to have accepted the viral haemorrhagic fever diagnosis, and became more interested in assessing how the disease became so widespread[2][3][15].

Bacterial Genomic Study

In 2018, Johannes Krause, an evolutionary geneticist at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, and colleagues discovered new evidence for an Old World culprit[4]. The team extracted ancient DNA from the teeth of 29 individuals buried at Teposcolula-Yucundaa in Oaxaca, Mexico. The Contact-era site has the only cemetery to be conclusively linked to victims of the Cocoliztli Outbreak of 1545-1548. Using the MEGAN alignment tool (MALT), a program that attempts to match fragments of extracted DNA with a database of bacterial genomes, the researchers were able to recognize nonlocal microbial infections.

Within 10 individuals, they identified Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Paratyphi C, which causes enteric fevers in humans[21]. This strain of Salmonella is unique to humans, and was not found in any soil samples or pre-Contact individuals that were used as controls. Enteric fevers, also known as typhoid or paratyphoid, are similar to typhus, and were only distinguished from one another in the 19th century[22]. The bacteria itself is a descendant from the same lineage of S. enterica that contains the serovars Choleraesuis and Typhisuis, both of which are swine pathogens[23]. It is transmitted most often through the consumption of food or water that is contaminated with fecal matter[21]. Today, S. Paratyphi C continues to cause enteric fevers, and if untreated, has a mortality rate up to 15%[24]. Infections are largely limited to developing nations in Africa and Asia, although enteric fevers, in general, are still a health threat world wide[25]. Infections with S. Paratyphi C are rare, as the majority of cases reported (about 27 million in 2000) were the result of the serovars S. Typhi and S. Paratyphi A[4][26].

DNA evidence from 11 individuals buried at a Mixtec cemetery in southern Mexico has offered new clues. Dr. Kirsten Bos, Group leader of Molecular Palaeopathology at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History and her team have re-purposed the metagenomics method and noticed that " a specific strain of Salmonella enterica popped up repeatedly. Dental pulp samples from five people who died before European contact but buried in the same site contained no significant amounts of S. enterica." [27].

These findings are boosted by the recent discovery of S. Paratyphi C within a 13th century Norwegian cemetery[23]. A young female, who likely died from an enteric fever, is proof that the pathogen was present in Europe over 300 years before the epidemics in Mexico. Thus, it is possible that healthy carriers transported the bacteria to the New World, where it thrived. Those who unknowingly possessed the bacteria were likely aided from generations of contact with it, as it is believed that S. Paratyphi C may have first transferred over to humans from swine in the Old World during, or, shortly after the Neolithic period[23].

However, María Ávila-Arcos, also an evolutionary geneticist, has cautioned against accepting S. Paratyphi C as solely responsible[24]. Both Ávila-Arcos, and even Krause’s team, point out the fact that RNA viruses, among other non-bacterial pathogens, had not been screened for or investigated. Others have highlighted the fact that certain symptoms described, including gastrointestinal hemorrhaging, are not present in current observations of S. Paratyphi C infections[10]. Ultimately, the Cocoliztli Outbreak of 1545-1548 is likely to be multi-faceted and the result of multiple pathogens working simultaneously and synergistically[4]. Additional bacterial genomic studies, as well as, developing methods to improve the detection of viruses in the archaeological record will be vital in solving the mystery of cocoliztli.

Sources and vectors

The social and physical environment of Colonial Mexico was likely key in allowing the Outbreak of 1545-1548 to reach that heights that it did. Already weakened by war and earlier disease outbreaks, the Aztecs were forced into easily governable reducciones (congregations) that focused on agricultural production and conversion to Christianity[28][29]. The reducciones would have not only brought people in much closer contact to one another, but with animals, as well. Whether it is rats, chickens, pigs, or cattle, animals imported from the Old World were potentially disease vectors for illnesses of New and Old World origins.

At the same time, droughts plagued Central America, with tree-ring data showing that the outbreak occurred in the midst of a megadrought[3]. The lack of water would have altered sanitary conditions and encouraged poor hygiene habits. Additionally, periodic rains during a supposed megadrought, such as those hypothesized for shortly before 1545, would have increased the presence of New World rats and mice[3][5]. These animals are believed to have also been able to transport the arenaviruses capable of causing hemorrhagic fevers[20]. The effects of drought, combined with the now crowded settlements, is a highly plausible explanation for disease transmission, especially if the pathogens are spread by either human fecal matter or animals.

As alluded to above, the Aztecs and other indigenous groups affected by the outbreak were potentially put at a disadvantage given their lack of exposure to zoonotic diseases. Many “crowd-type ecopathogenic diseases,” enteric fevers included, were not present in the New World during Pre-Columbian times[30]. Given that many of the Old World pathogens being considered as responsible for the cocoliztli outbreak, it is significant that all but one of the most common species of domestic mammalian livestock (llamas/alpacas being the exception) come from the Old World[31]. This gave Europeans, Asians, and Africans generations of relatively large exposure to diseases with zoonotic origins. People native to the New World are not expected to possess the same level of immunity to the various diseases, especially bacterial ones that were introduced by the Spanish and their African slaves[11]. With deteriorating sanitary conditions and access to a large, concentrated population of susceptible hosts, S. Paratyphi C and other Old World pathogens likely prospered.

Later outbreaks

A second large outbreak of cocoliztli occurred in 1576, lasting until about 1580[1]. Although less destructive (around 2 million deaths) than its predecessor, this outbreak appears in much greater detail in colonial accounts[5][6]. Many of the descriptions of cocoliztli symptoms, beyond the bleeding, fevers, and jaundice, were recorded during this epidemic. In total, there are 13 cocoliztli epidemics cited in Spanish accounts between 1545 and 1642, with a later outbreak in 1736 taking a similar form, but referred to by a different name (tlazahuatl)[2]. Some indigenous people revolted against the Spanish administrators throughout the 16th and 17th centuries, but with populations so diminished and fractioned partly due to various disease epidemics, efforts were often easily thwarted[9]. Today, researchers are still concerned that the causal agent, or agents, have not been conclusively identified. Fears revolve around the possible reemergence of similar hemorrhagic fevers in Mexico, and the possible effects they would have on a densely populated area such as Mexico City[2][3][15]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Prem, Hanns (1991). "Disease Outbreaks in Central Mexico During the Sixteenth Century". In Cook, Noble David; Lovell, W. George. "Secret Judgments of God": Old World Disease in Colonial Spanish America. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 20–48. ISBN 0806123729.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Acuña-Soto, Roldalfo; Calderón Romero, Leticia; Maguire, James (2000). "Large epidemics of hemorrhagic fevers in Mexico 1545-1815". The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 62 (6): 733–739.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Acuno-Soto, Roldolfo; Stahle, David; Cleaveland, Malcolm; Therrell, Matthew (2002). "Megadrought and Megadeath in 16th Century Mexico". Revista Biomédica. 13: 289–292.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Vågene, Åshild; et al. (2018). "Salmonella enterica genomes from victims of a major sixteenth-century epidemic in Mexico". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 2: 520–520. doi:10.1038/s41559-017-0446-6.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Marr, John; Kiracofe, James (2000). "Was the Huey Cocoliztli a Haemorrhagic Fever?". Medical History. 44: 341–362.

- 1 2 3 4 Somolinos d'Ardois, Germaine (1970). "La epidemia de Cocoliztli de 1545 senalada en un codice". Tribuna Medica. 15 (4): 85.

- 1 2 3 Warinner, Christina; et al. (2012). "Disease, demography, and diet in early colonial New Spain: investigation of a sixteenth-century Mixtec cemetery at Teposcolula Yucundaa". Latin American Antiquity. 23 (4): 467–489.

- ↑ Siek, Thomas (2013). "The Osteological Paradox and Issues of Interpretation in Paleopathology". vis-à-vis: Explorations in Anthropology. 12 (1): 92–101.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Reff, Daniel (1991). Disease, Depopulation, and Culture Change in Northwestern New Spain, 1518-1764. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press. ISBN 0874803551.

- 1 2 3 Puente, Jose Luis; Calva, Edmundo (2017). "The One Health Concept—the Aztec empire and beyond". Pathogens and Disease. 75. doi:10.1093/femspd/ftx062.

- 1 2 McMichael, Anthony; Weiss, Robin (2015). "Social and Environmental Risk Factors in the Emergence of Infectious Diseases (Reprint)". In Butler, Colin; Dixon, Jane. Health Of People, Places And Planet: reflections based on Tony McMichael’s four decades of contribution to epidemiological understanding. Acton: Australia National University Press. pp. 431–440. ISBN 9781925022407.

- 1 2 Lovell, W. George (1991). "Disease and Depopulation in Early Colonial Guatemala". In Cook, Noble David; Lovell, W. George. Secret Judgments of God": Old World Disease in Colonial Spanish America. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 49–83. ISBN 0806123729.

- ↑ Newson, Linda (1991). "Old World Epidemics in Ecuador". In Cook, Noble David; Lovell, W. George. Secret Judgments of God": Old World Disease in Colonial Spanish America. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 84–112. ISBN 0806123729.

- ↑ Evans, Brian (1991). "Death in Aymaya of Upper Peru, 1580-1623". In Cook, Noble David; Lovell, W. George. "Secret Judgments of God": Old World Disease in Colonial Spanish America. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0806123729.

- 1 2 3 Acuna-Soto, Rodolfo; et al. (2004). "When half of the population died: the epidemic of hemorrhagic fevers of 1576 in Mexico". FEMS Microbiology Letters. 240 (1): 1–5.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Gibson, Charles (1964). The Aztecs Under Spanish Rule: A history of the Indians of the Valley of Mexico 1519-1810. Standford: Stanford University Press.

- ↑ Cuello, Jose (1988). "The persistence of indian slavery and encomienda in the northeast of colonial Mexico, 1577-1723". Journal of Social History. 21 (4): 683–700.

- ↑ Espinsoa, Aurelio (2006). "The Spanish Reformation: Institutional Reform, Taxation, And The Secularization Of Ecclesiastical Properties Under Charles V". The Sixteenth Century Journal. 37 (1): 3–24.

- ↑ Prem, Hanns (1992). "Spanish colonization and Indian property in central Mexico, 1521–1620". Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 82 (3): 444–459.

- 1 2 Bowen, Michael; Peters, Clarence; Nichol, Stuart (1997). "Phylogenetic Analysis of theArenaviridae: Patterns of Virus Evolution and Evidence for Cospeciation between Arenaviruses and Their Rodent Hosts". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 8 (3): 301–316.

- 1 2 Judd, Michael; Mintz, Eric (2014). "Chapter 3: Typhoid & Paratyphoid Fever". In Newton, Anna. CDC Health Information for International Travel: The Yellow Book. Oxford: Oxford Press. ISBN 9780199948499.

- ↑ Smith, Dale (1980). "Gerhard's distinction between typhoid and typhus and its reception in America, 1833-1860". Bulletin of the History of Medicine. 54 (3): 368–385.

- 1 2 3 Zhou, Zhemin; et al. (2017). "Millennia of genomic stability within the invasive Para C Lineage of Salmonella enterica". bioRxiv. doi:10.1101/105759.

- 1 2 Callaway, Ewen. "Collapse of Aztec society linked to catastrophic salmonella outbreak". nature.com. Retrieved 20 February 2018.

- ↑ "2014 National Typhoid and Paratyphoid Fever Surveillance Annual Summary" (PDF). CDC. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- ↑ Crump, John; Luby, Stephen; Mintz, Eric (2004). "The Global Burden of Typhoid Fever". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 82: 346–353.

- ↑ Zhang, Sarah. "A New Clue to the Mystery Disease That Once Killed Most of Mexico". Retrieved 15 January 2018.

- ↑ Cordova, Carlos; Parsons, Jeffery (1997). "Geoarchaeology of an Aztec dispersed village on the Texcoco piedmont of Central Mexico". Geoarchaeology: An International Journal. 12 (3): 177–210.

- ↑ Rice, Prudence (2012). "Torata Alta: An Inka Administrative Center and Spanish Colonial Reducción in Moquegua, Peru". Latin America Antiquity. 23 (1): 3–28.

- ↑ Newman, Marshall (1976). "Aboriginal New World epidemiology and medical care, and the impact of Old World disease imports". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 45 (3): 667–672.

- ↑ Wolfe, Nathan; Dunavan, Claire; Diamond, Jared (2007). "Origins of Major Human Infectious Diseases". Nature. 447 (7142).