Song of the South

| Song of the South | |

|---|---|

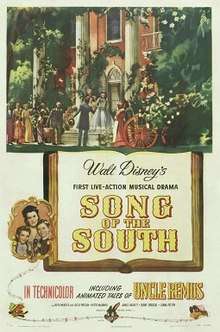

Original theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by |

|

| Produced by | Walt Disney |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Based on |

Uncle Remus by Joel Chandler Harris |

| Starring | |

| Music by | |

| Cinematography | Gregg Toland |

| Edited by | William M. Morgan |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | RKO Radio Pictures |

Release date | |

Running time | 94 minutes[2] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | US$2.125 million[3] |

| Box office | US$65 million[4] |

Song of the South is a 1946 American live-action/animated musical film produced by Walt Disney and released by RKO Radio Pictures. It is based on the collection of Uncle Remus stories as adapted by Joel Chandler Harris, and stars James Baskett as Uncle Remus. The film takes place in the southern United States during the Reconstruction Era, a period of American history shortly after the end of the American Civil War and the abolition of slavery. The story follows 7-year-old Johnny (Bobby Driscoll) who is visiting his grandmother's plantation for an extended stay. Johnny befriends Uncle Remus, one of the workers on the plantation, and takes joy in hearing his tales about the adventures of Br'er Rabbit, Br'er Fox, and Br'er Bear. Johnny learns from the stories how to cope with the challenges he is experiencing living on the plantation.

Walt Disney had wanted to produce a film based on the Uncle Remus stories for some time. It was not until 1939 that he began negotiating with the Harris family for film rights, and later in 1944, filming for Song of the South finally began. The studio constructed a plantation set for the outdoor scenes in Phoenix, Arizona, and some other scenes were filmed in Hollywood. The film is mostly live action, but includes three animated segments, which were later released as stand-alone television features. Some scenes also feature a combination of live action with animation. Song of the South premiered in Atlanta in November 1946 and the remainder of its initial theater run was a financial success. The song "Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah" won the 1947 Academy Award for Best Original Song and Baskett received an Honorary Academy Award for his performance as Uncle Remus.

Since its release, Song of the South has remained a subject of controversy. Some critics have described the film's portrayal of African Americans as racist and offensive, pointing out the black vernacular and other qualities as stereotypes. In addition, the plantation setting is sometimes criticized as idyllic and glorified. Because of this controversy, Disney has yet to release Song of the South on any home video format in the United States. Some of the musical and animated sequences have been released through other means, and the full film has seen home video distribution in other countries around the world. The cartoon characters from the film have continued to remain popular for decades, being featured in a variety of books, comics, and other media. The Disney theme park ride Splash Mountain is also based on the film.

Synopsis

Setting

The film is set on a plantation in the southern United States, specifically in the state of Georgia, some distance from Atlanta. Although sometimes misinterpreted as taking place before the American Civil War while slavery was still legal in the region, the film takes place during the Reconstruction Era after slavery was abolished.[5][6][7][8] Harris' original Uncle Remus stories were all set after the American Civil War and the abolition of slavery. Harris himself, born in 1848, was a racial reconciliation activist writer and journalist of the Reconstruction Era. The film makes several indirect references to the Reconstruction Era: clothing is in the newer late-Victorian style; Uncle Remus is free to leave the plantation at will; black field hands are sharecroppers, etc.[9]

Plot

Seven-year-old Johnny (Bobby Driscoll) is excited about what he believes to be a vacation at his grandmother's Georgia plantation with his parents, John Sr. (Erik Rolf) and Sally (Ruth Warrick). When they arrive at the plantation, he discovers that his parents will be living apart for a while, and he is to live at the plantation with his mother and grandmother (Lucile Watson) while his father returns to Atlanta to continue his controversial editorship in the city's newspaper. Johnny, distraught because of his father's departure, secretly sets off that night for Atlanta with only a bindle.

As Johnny sneaks away from the plantation, he is attracted by the voice of Uncle Remus (James Baskett) telling tales of a character named Br'er Rabbit. By this time, word had gotten out that Johnny was missing, and some plantation residents are looking for him. Johnny evades being discovered, but Uncle Remus catches up with him. They befriend each other and Uncle Remus offers him some food for his journey, taking him back to his cabin. Back at the cabin, Uncle Remus tells Johnny the traditional African-American folktale, "Br'er Rabbit Earns a Dollar a Minute". In the story, Br'er Rabbit (Johnny Lee) attempts to run away from home only to change his mind after an encounter with Br'er Fox and Br'er Bear (James Baskett and Nick Stewart). Johnny takes the advice and changes his mind about leaving the plantation, letting Uncle Remus take him back to his mother.

Johnny makes friends with Toby (Glenn Leedy), a young black boy who lives on the plantation, and Ginny Favers (Luana Patten), a poor white girl. Ginny gives Johnny a puppy after her two older brothers, Joe (Gene Holland) and Jake (George Nokes), threaten to drown it. Johnny's mother refuses to let him take care of the puppy, so he takes the dog to Uncle Remus. Uncle Remus takes the dog in and delights Johnny and his friends with the fable of Br'er Rabbit and the Tar-Baby, stressing that people shouldn't get involved with something they have no business with in the first place. Johnny heeds the advice of how Br'er Rabbit used reverse psychology on Br'er Fox and begs the Favers Brothers not to tell their mother (Mary Field) about the dog. The reverse psychology works, and the boys go to speak with their mother. After being spanked, they realize that Johnny had fooled them. In an act of revenge, they tell Sally about the dog. She becomes upset that Johnny and Uncle Remus kept the dog despite her order (which was unknown to Uncle Remus). She instructs Uncle Remus not to tell any more stories to her son.

Johnny's birthday arrives and Johnny picks up Ginny to take her to his party. On the way there, Joe and Jake push Ginny into a mud puddle. With her dress ruined, Ginny is unable to go to the party and runs off crying. Johnny begins fighting with the boys, but their fight is broken up by Uncle Remus. Johnny runs off to comfort Ginny. He explains that he does not want to go either, especially since his father will not be there. Uncle Remus discovers both dejected children and cheers them up by telling the story of Br'er Rabbit and his "Laughing Place". When the three return to the plantation, Sally becomes angry at Johnny for missing his own birthday party, and tells Uncle Remus not to spend any more time with him. Saddened by the misunderstanding of his good intentions, Uncle Remus packs his bags and leaves for Atlanta. Johnny rushes to intercept him, but is attacked by a bull and seriously injured after taking a shortcut through a pasture. While Johnny hovers between life and death, his father returns. Johnny calls for Uncle Remus, who is then escorted in by his grandmother. Uncle Remus begins telling a tale of Br'er Rabbit and the Laughing Place, and the boy miraculously survives.

Johnny, Ginny, and Toby are next seen skipping along and singing while Johnny's returned puppy runs alongside them. Uncle Remus is also in the vicinity and he is shocked when Br'er Rabbit and several of the other characters from his stories appear in front of them and interact with the children. Uncle Remus rushes to join the group, and they all skip away singing.

Cast

- James Baskett as Uncle Remus

- Bobby Driscoll as Johnny

- Luana Patten as Ginny Favers

- Glenn Leedy as Toby

- Ruth Warrick as Sally

- Lucile Watson as Grandmother

- Hattie McDaniel as Aunt Tempy

- Erik Rolf as John

- Olivier Urbain as Mr. Favers (uncredited)

- Mary Field as Mrs. Favers

- Anita Brown as Maid

- George Nokes as Jake Favers

- Gene Holland as Joe Favers

Voices

- Johnny Lee as Br'er Rabbit

- James Baskett as Br'er Fox

- Nick Stewart as Br'er Bear

- Roy Glenn as Br'er Frog (uncredited)

- Clarence Nash as Bluebird (uncredited)

- Helen Crozier as Mother Possum (uncredited)

Production

Background

Walt Disney had long wanted to produce a film based on the Uncle Remus storybook, but it was not until the mid-1940s that he had found a way to give the stories an adequate film equivalent in scope and fidelity. "I always felt that Uncle Remus should be played by a living person", Disney commented, "as should also the young boy to whom Harris' old Negro philosopher relates his vivid stories of the Briar Patch. Several tests in previous pictures, especially in The Three Caballeros, were encouraging in the way living action and animation could be dovetailed. Finally, months ago, we 'took our foot in hand,' in the words of Uncle Remus, and jumped into our most venturesome but also more pleasurable undertaking."[10]

Disney first began to negotiate with Harris' family for the rights in 1939, and by late summer of that year he already had one of his storyboard artists summarize the more promising tales and draw up four boards' worth of story sketches.[4] In November 1940, Disney visited the Harris' home in Atlanta. He told Variety that he wanted to "get an authentic feeling of Uncle Remus country so we can do as faithful a job as possible to these stories."[4] Roy Oliver Disney had misgivings about the project, doubting that it was "big enough in caliber and natural draft" to warrant a budget over $1 million and more than twenty-five minutes of animation, but in June 1944, Disney hired Southern-born writer Dalton Reymond to write the screenplay, and he met frequently with King Vidor, whom he was trying to interest in directing the live-action sequences.[4]

Dalton Reymond wrote a treatment for the film.[5] Because Reymond was not a professional screenwriter, Maurice Rapf, who had been writing live-action features at the time, was asked by Walt Disney Productions to work with Reymond and co-writer Callum Webb to turn the treatment into a shootable screenplay.[5] According to Neal Gabler, one of the reasons Disney had hired Rapf to work with Reymond was to temper what Disney feared would be Reymond's "white Southern slant".

Rapf was a minority, a Jew, and an outspoken left-winger, and he himself feared that the film would inevitably be Uncle Tomish. "That's exactly why I want you to work on it," Walt told him, "because I know that you don't think I should make the movie. You're against Uncle Tomism, and you're a radical."[4]

Rapf initially hesitated, but when he found out that most of the film would be live-action and that he could make extensive changes, he accepted the offer.[5] Rapf worked on Uncle Remus for about seven weeks. When he got into a personal dispute with Reymond, Rapf was taken off the project.[5] According to Rapf, Walt Disney "ended every conference by saying 'Well, I think we've really licked it now.' Then he'd call you the next morning and say, 'I've got a new idea.' And he'd have one. Sometimes the ideas were good, sometimes they were terrible, but you could never really satisfy him."[4] Morton Grant was assigned to the project.[5] Disney sent out the script for comment both within the studio and outside the studio.[4]

Casting

Song of the South was the first live-action dramatic film made by Disney.[11] James Baskett was cast as Uncle Remus after responding to an ad for providing the voice of a talking butterfly. "I thought that, maybe, they'd try me out to furnish the voice for one of Uncle Remus' animals," Baskett is quoted as saying. Upon review of his voice, Disney wanted to meet Baskett personally, and had him tested for the role of Uncle Remus. Not only did Baskett get the part of the butterfly's voice, but also the voice of Br'er Fox and the live-action role of Uncle Remus as well.[12] Additionally, Baskett filled in as the voice of Br'er Rabbit for Johnny Lee in the "Laughing Place" scene after Lee was called away to do promotion for the picture.[11] Disney liked Baskett, and told his sister Ruth that Baskett was "the best actor, I believe, to be discovered in years". Even after the film's release, Disney maintained contact with Baskett.[4] Disney also campaigned for Baskett to be given an Academy Award for his performance, saying that he had worked "almost wholly without direction" and had devised the characterization of Remus himself. Thanks to Disney's efforts, Baskett won an honorary Oscar in 1948.[4][5] After Baskett's death, his widow wrote Disney and told him that he had been a "friend indeed and [we] certainly have been in need".[4]

Also cast in the production were child actors Bobby Driscoll, Luana Patten, and Glenn Leedy (his only screen appearance). Driscoll was the first actor to be under a personal contract with the Disney studio.[13] Patten had been a professional model since age 3, and caught the attention of Disney when she appeared on the cover of Woman's Home Companion magazine.[14] Leedy was discovered on the playground of the Booker T. Washington school in Phoenix, Arizona, by a talent scout from the Disney studio.[15] Ruth Warrick and Erik Rolf, cast as Johnny's mother and father, had actually been married during filming, but divorced in 1946.[16][17] Hattie McDaniel also appeared in the role of Aunt Tempy.

Filming

Production started under the title Uncle Remus.[4][5] The budget was originally $1,350,000.[18] The animated segments of the film were directed by Wilfred Jackson, while the live-action segments were directed by Harve Foster.[4] Filming began in December 1944 in Phoenix, where the studio had constructed a plantation and cotton fields for outdoor scenes, and Disney left for the location to oversee what he called "atmospheric shots".[4] Back in Hollywood, the live action scenes were filmed at the Samuel Goldwyn Studio.

On the final day of shooting, Jackson discovered that the scene in which Uncle Remus sings the film's signature song, "Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah", had not been properly blocked. According to Jackson, "We all sat there in a circle with the dollars running out, and nobody came up with anything. Then Walt suggested that they shoot Baskett in close-up, cover the lights with cardboard save for a sliver of blue sky behind his head, and then remove the cardboard from the lights when he began singing so that he would seem to be entering a bright new world of animation. Like Walt's idea for Bambi on ice, it made for one of the most memorable scenes in the film."[4]

Animation

There are three animated segments in the film (in all, they last a total of 25 minutes). The last few minutes of the film also contain combine animation with live-action. The three sequences were later shown as stand-alone cartoon features on television.

- Br'er Rabbit Runs Away: (~8 minutes) Based on "Br'er Rabbit Earns a Dollar a Minute". Includes the song "Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah",

- Br'er Rabbit and the Tar Baby: (~12 minutes) Based on "Tar-Baby". The segment is interrupted with a short live-action scene about two-thirds through. It features the song "How Do You Do?"

- Br'er Rabbit's Laughing Place: (~5 minutes) Based on "The Laughing Place". The song "Everybody's Got a Laughing Place" is featured.

Music

Nine songs are heard in the film, with four reprises. Nearly all of the vocal performances are by the largely African-American cast, and the renowned all-black Hall Johnson Choir sing four pieces: two versions of a blues number ("Let the Rain Pour Down"), one chain-reaction-style folk song[19] ("That's What Uncle Remus Said") and one spiritual ("All I Want").

The songs are, in film order, as follows:

- "Song of the South": Written by Sam Coslow and Arthur Johnston; performed by the Disney Studio Choir

- "Uncle Remus Said": Written by Eliot Daniel, Hy Heath, and Johnny Lange; performed by the Hall Johnson Choir

- "Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah": Written by Allie Wrubel and Ray Gilbert; performed by James Baskett

- "Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah": (reprise) Performed by Bobby Driscoll

- "Who Wants to Live Like That?": Written by Ken Darby and Foster Carling; performed by James Baskett

- "Let the Rain Pour Down": (uptempo) Written by Ken Darby and Foster Carling; performed by the Hall Johnson Choir

- "How Do You Do?": Written by Robert MacGimsey; performed by Johnny Lee and James Baskett

- "How Do You Do?": (reprise) Performed by Bobby Driscoll and Glenn Leedy

- "Sooner or Later": Written by Charles Wolcott and Ray Gilbert; performed by Hattie McDaniel

- "Everybody's Got a Laughing Place": Written by Allie Wrubel and Ray Gilbert; performed by James Baskett and Nick Stewart

- "Let the Rain Pour Down": (downtempo) Written by Ken Darby and Foster Carling; performed by the Hall Johnson Choir

- "All I Want": Traditional, new arrangement and lyrics by Ken Darby; performed by the Hall Johnson Choir

- "Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah": (reprise) Performed by Bobby Driscoll, Luana Patten, Glenn Leedy, Johnny Lee, and James Baskett

- "Song of the South": (reprise) Performed by the Disney Studio Choir

"Let the Rain Pour Down" is set to the melody of "Midnight Special", a traditional blues song popularized by Lead Belly (Huddie William Ledbetter). The song title "Look at the Sun" appeared in some early press books, though it is not actually in the film. The song "Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah" was influenced by the chorus of the pre-Civil War folk song "Zip Coon", that is considered racist as it plays on an African American stereotype.[20][21]

Release

The film premiered on November 12, 1946, at the Fox Theater in Atlanta.[4] Walt Disney made introductory remarks, introduced the cast, then quietly left for his room at the Georgian Terrace Hotel across the street; he had previously stated that unexpected audience reactions upset him and he was better off not seeing the film with an audience. James Baskett was unable to attend the film's premiere because he would not have been allowed to participate in any of the festivities, as Atlanta was then a racially segregated city.[22] The film grossed $3.3 million at the box office.[4][23]

As had been done earlier with Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Disney produced a Sunday comic strip titled Uncle Remus & His Tales of Br'er Rabbit to give the film pre-release publicity. The strip was launched by King Features on October 14, 1945, more than a year before the film was released. Unlike the Snow White comic strip, which only adapted the film, Uncle Remus ran for decades, telling one story after another about the characters, some based on the legends and others new, until it ended on December 31, 1972.[24] Apart from the newspaper strips, Disney Br'er Rabbit comics were also produced for comic books; the first such stories appeared in late 1946. Produced both by Western Publishing and European publishers such as Egmont, they continue to appear.[25]

In 1946, a Giant Golden Book entitled Walt Disney's Uncle Remus Stories was published by Simon & Schuster. It featured 23 illustrated stories of Br'er Rabbit's escapades, all told in a Southern dialect based on the original Joel Chandler Harris stories.

Song of the South was re-released in theaters several times after its original premiere, each time through Buena Vista Pictures: in 1956 for the 10th anniversary; in 1972 for the 50th anniversary of Walt Disney Productions; in 1973 as the second half of a double bill with The Aristocats; in 1980 for the 100th anniversary of Harris' classic stories; and in 1986 for the film's own 40th anniversary and in promotion of the upcoming Splash Mountain attraction at Disneyland. The film has been broadcast on European television, including the BBC as recently as 2006.[26]

Home media

The Walt Disney Company has yet to release a complete version of the film in the United States on home video given the film's controversial reputation.[27][28] Over the years, Disney has made a variety of statements about whether and when the film would be re-released.[29][30][31][32] In March 2010, Disney CEO Robert Iger stated that there were no plans to release the movie on DVD, calling the film "antiquated" and "fairly offensive".[33] On November 15, 2010, Disney creative director Dave Bossert stated in an interview, "I can say there's been a lot of internal discussion about Song of the South. And at some point we're going to do something about it. I don't know when, but we will. We know we want people to see Song of the South because we realize it's a big piece of company history, and we want to do it the right way."[34] Film critic Roger Ebert, who normally disdained any attempt to keep films from any audience, supported the non-release position, claiming that most Disney films become a part of the consciousness of American children, who take films more literally than do adults. However, he favored allowing film students to have access to the film.[35][36]

Despite not having a home video release in the United States, audio from the film—both the musical soundtrack and dialogue—were made widely available to the public from the time of the film's debut up through the late 1970s. In particular, many book-and-record sets were released, alternately featuring the animated portions of the film or summaries of the film as a whole.[37] The Walt Disney Company has also allowed key portions of the film to be issued on many VHS and DVD compilations in the U.S., as well as on the long-running Walt Disney anthology television series. Most recently, "Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah" and some of the animated portions of the film were issued on the Alice in Wonderland 2-DVD Special Edition set. These segments are part of a 1950 Walt Disney TV special included on the DVD which promoted the then-forthcoming Alice in Wonderland film.

The full-length film has been released in various European, Latin American, and Asian countries. In the UK, it was released on PAL VHS tape in 1982 and again in 1991. In Japan it appeared on NTSC VHS, Beta, and LaserDisc in 1985 then again on LaserDisc in 1990 with subtitles during songs (additionally, under Japanese copyright law, the film is now in the public domain).[38] A NTSC LaserDisc was released in Hong Kong for the Chinese rental market by Intercontinental Video Ltd, which has been the exclusive distributor of Walt Disney Studios since 1988. This release appears to have been created from a PAL videotape, and has a 4% faster running time because of its PAL source.[39][40] While most foreign releases of the film are literal translations of the English title, the German title, Onkel Remus' Wunderland, translates to "Uncle Remus' Wonderland", the Italian title, I Racconti Dello Zio Tom, translates to "The Stories of Uncle Tom",[41] and the Norwegian title Onkel Remus forteller translates to "Storyteller Uncle Remus."[42]

In July 2017 after being inaugurated as a Disney Legend, Whoopi Goldberg expressed a desire for Song of the South to be re-released publicly to American audiences.[43]

Reception

Although the film was a financial success, netting the studio a profit of $226,000 ($2,833,970 in 2017 dollars) [44] some critics were less enthusiastic about the film, not so much the animated portions as the live-action portions. Bosley Crowther for one wrote in The New York Times, "More and more, Walt Disney's craftsmen have been loading their feature films with so-called 'live action' in place of their animated whimsies of the past, and by just those proportions has the magic of these Disney films decreased", citing the ratio of live action to animation at two to one, concluding that is "approximately the ratio of its mediocrity to its charm".[4] However, the film also received positive notice. Time magazine called the film "topnotch Disney".[5] In 2003, the Online Film Critics Society ranked the film as the 67th greatest animated film of all time.[45] On Rotten Tomatoes, the film has a 55% approval rating, based on 11 reviews, with an average rating of 5.8/10.[46]

Accolades

The score by Daniele Amfitheatrof, Paul J. Smith, and Charles Wolcott was nominated in the "Scoring of a Musical Picture" category, and "Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah", written by Allie Wrubel and Ray Gilbert, won the award for Best Song at the 20th Academy Awards on March 20, 1948.[47] A special Academy Award was given to Baskett "for his able and heart-warming characterization of Uncle Remus, friend and story teller to the children of the world in Walt Disney's Song of the South". Bobby Driscoll and Luana Patten in their portrayals of the children characters Johnny and Ginny were also discussed for Academy Juvenile Awards, but in 1947 it was decided not to present such awards at all.[48]

The film is recognized by American Film Institute in these lists:

- 2004: AFI's 100 Years...100 Songs:

- "Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah" – #47[49]

- 2006: AFI's Greatest Movie Musicals – Nominated[50]

Controversies

The film has received significant controversy for its handling of race.[51] Cultural historian Jason Sperb describes the film as "one of Hollywood's most resiliently offensive racist texts".[52] Sperb, Neal Gabler, and other critics have noted the film's release as being in the wake of the Double V campaign, a propaganda campaign in the United States during World War II to promote victory over racism in the United States and its armed forces, and victory over fascism abroad.[53] Early in the film's production, there was concern that the material would encounter controversy. Disney publicist Vern Caldwell wrote to producer Perce Pearce that "the negro situation is a dangerous one. Between the negro haters and the negro lovers there are many chances to run afoul of situations that could run the gamut all the way from the nasty to the controversial."[4]

The Disney Company has stated that, like Harris' book, the film takes place after the American Civil War and that all the African American characters in the movie are no longer slaves.[9] The Hays Office had asked Disney to "be certain that the frontispiece of the book mentioned establishes the date in the 1870s"; however, the final film carried no such statement.[5]

When the film was first released, Walter Francis White, the executive secretary of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), telegraphed major newspapers around the country with the following statement, erroneously claiming that the film depicted an antebellum setting:

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People recognizes in "Song of the South" remarkable artistic merit in the music and in the combination of living actors and the cartoon technique. It regrets, however, that in an effort neither to offend audiences in the north or south, the production helps to perpetuate a dangerously glorified picture of slavery. Making use of the beautiful Uncle Remus folklore, "Song of the South" unfortunately gives the impression of an idyllic master-slave relationship which is a distortion of the facts.[5]

White however had not yet seen the film; his statement was based on memos he received from two NAACP staff members – Norma Jensen and Hope Spingarn – who attended a press screening on November 20, 1946. Jensen had written that the film was "so artistically beautiful that it is difficult to be provoked over the clichés" but that it contained "all the clichés in the book", mentioning that she felt scenes like blacks singing traditional black songs were offensive as a stereotype. Spingarn listed several things she found objectionable from the film, including the use of African-American English.[5] Jim Hill Media stated that both Jensen and Spingarn were confused by the film's Reconstruction setting, writing that "It was something that also confused other reviewers who from the tone of the film and the type of similar recent Hollywood movies [Gone with the Wind; Jezebel] assumed it must also be set during the time of slavery." Based on the Jensen and Spingarn memos, White released the "official position" of the NAACP in a telegram that was widely quoted in newspapers.[54] The New York Times' Bosley Crowther made a similar assumption, writing that the movie was a "travesty on the antebellum South."[55]

Time magazine, although it praised the film, cautioned that it was "bound to land its maker in hot water", because the character of Uncle Remus was "bound to enrage all educated Negroes and a number of damyankees".[56] Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., a congressman from Harlem, branded the film an "insult to American minorities [and] everything that America as a whole stands for."[57] The National Negro Congress set up picket lines in theaters in the big cities where the film played, with its protesters holding signs that read "Song of the South is an insult to the Negro people" and, lampooning "Jingle Bells", chanted: "Disney tells, Disney tells/lies about the South."[57] On April 2, 1947, a group of protesters marched around Paramount Theatre (Oakland, California) with picket signs reading, "We want films on Democracy not Slavery" and "Don't prejudice children's minds with films like this".[58] Jewish newspaper B'nai B'rith Messenger of Los Angeles considered the film to be "tall[ying] with the reputation that Disney is making for himself as an arch-reactionary".

Some black press had mixed reactions on what they thought of Song of the South. While Richard B. Dier in The Afro-American was "thoroughly disgusted" by the film for being "as vicious a piece of propaganda for white supremacy as Hollywood ever produced," Herman Hill in The Pittsburgh Courier felt that Song of the South would "prove of inestimable goodwill in the furthering of interracial relations", and considered criticisms of the film to be "unadulterated hogwash symptomatic of the unfortunate racial neurosis that seems to be gripping so many of our humorless brethren these days."[59]

Despite a lack of public release in the US in 1986, Song of the South has made its way around in the form of bootleg copies found around numerous internet message boards. The film has grown an online following that has kept the film's presence alive, despite the general audience's views on the film, according to Jason Sperb.[60]

Legacy

As early as October 1945, a newspaper strip named Walt Disney Presents "Uncle Remus" and His Tales of Br'er Rabbit appeared in the United States, and this production continued until 1972. There have also been episodes for the series produced for the Disney comic books worldwide, in the U.S., Denmark and the Netherlands, from the 1940s up to the present day, 2012.[61] Br'er Bear and Br'er Fox also appeared frequently in Disney's Big Bad Wolf stories, although here, Br'er Bear was usually cast as an honest farmer and family man, instead of the bad guy in his original appearances.

Br'er Rabbit, Br'er Fox and Br'er Bear appeared as guests in Disney's House of Mouse. They also appeared in Mickey's Magical Christmas: Snowed in at the House of Mouse. Br'er Bear and the Tar-Baby also appear in the film Who Framed Roger Rabbit. Br'er Bear can be seen near the end while the Toons are celebrating finding the will. The Tar-Baby can briefly be seen during the scene driving into Toon Town.

Br'er Rabbit, Br'er Fox and Br'er Bear also appeared in the 2011 video game Kinect Disneyland Adventures for the Xbox 360. The game is a virtual recreation of Disneyland and it features a mini game based on the Splash Mountain attraction. Br'er Rabbit helps guide the player character through that game, while Br'er Fox and Br'er Bear serve as antagonists. The three Br'ers also appear as meet-and-greet characters in the game, outside Splash Mountain in Critter Country. In the game, Jess Harnell reprises his role from the attraction as Br'er Rabbit and also takes on the role of Br'er Fox, while Br'er Bear is voiced by James Avery, who previously voiced Br'er Bear and Br'er Frog in the Walt Disney World version of Splash Mountain. This is the Br'ers' first major appearance in Disney media since The Lion King 1½ in 2004 and their first appearance as computer-generated characters.

References

- 1 2 "Song of the South: Detail View". American Film Institute. Retrieved April 29, 2014.

- ↑ "SONG OF THE SOUTH (U)". British Board of Film Classification. October 23, 1946. Retrieved November 28, 2015.

- ↑ Solomon, Charles (1989), p. 186. Enchanted Drawings: The History of Animation. ISBN 0-394-54684-9. Alfred A. Knopf. Retrieved February 16, 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Gabler, Neal (October 31, 2006). Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination. Knopf. pp. 432–9, 456, 463, 486, 511, 599. ISBN 0-679-43822-X.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Cohen, Karl F. (1997). Forbidden Animation: Censored Cartoons and Blacklisted Animators in America. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc. p. 64. ISBN 0-7864-2032-4.

- ↑ Kaufman, Will (2006). The Civil War in American Culture. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 0-7486-1935-6.

- ↑ Langman, Larry; Ebner, David (2001). Hollywood's Image of the South: A Century of Southern Films. Westport Connecticut, London: Greenwood Press. p. 169. ISBN 0-313-31886-7.

- ↑ Snead, James A.; MacCabe, Colin; West, Cornel (1994). White Screens, Black Images: Hollywood from the Dark Side. New York: Routledge. pp. 88, 93. ISBN 0-415-90574-5.

- 1 2 Walt Disney Presents "Song of the South" Promotional Program, Page 7. Published 1946 by Walt Disney Productions/RKO Radio Pictures.

- ↑ "The Movie: Background". Song of the South.net. Retrieved January 18, 2007.

- 1 2 "Trivia for Song of the South". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved January 18, 2007.

- ↑ "James Baskett as Uncle Remus". Song of the South.net. Retrieved January 18, 2007.

- ↑ Bobby Driscoll biography at Song of the South.net

- ↑ "Luana Patten as Ginny Favers". Song of the South.net. Retrieved January 18, 2007.

- ↑ "Glenn Leedy as Toby". Song of the South.net. Retrieved January 18, 2007.

- ↑ "Ruth Warrick as Sally". Song of the South.net. Retrieved January 18, 2007.

- ↑ "Eric Rolf as John". Song of the South.net. Retrieved January 18, 2007.

- ↑ Variety 12 September 1945 p 12

- ↑ Walt Disney's Song of the South, 1946 Publicity Campaign Book, Distributed by RKO Pictures. Copyright Walt Disney Pictures, 1946. "The chain-reaction, endless song, of which American folk music is so plentiful [...] The number is 'Uncle Remus Said,' and it consists of a single, brief melody repeated as often as new lyrics come along."

- ↑ Emerson, Ken (1997). Doo-dah!: Stephen Foster and the Rise of American Popular Culture. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 60. ISBN 978-0684810102.

- ↑ "Blackface!". black-face.com. Retrieved December 24, 2013.

- ↑ In a October 15, 1946 article in the Atlanta Constitution, columnist Harold Martin noted that to bring Baskett to Atlanta, where he would not have been allowed to participate in any of the festivities, "would cause him many embarrassments, for his feelings are the same as any man's". The modern claim that no Atlanta hotel would give Baskett accommodation is false: there were several black-owned hotels in the Sweet Auburn area of downtown Atlanta at the time, including the Savoy and the McKay. Atlanta's Black-Owned Hotels: A History.

- ↑ "Top Grossers of 1947", Variety, 7 January 1948 p 63

- ↑ Markstein, Don. "Br'er Rabbit". Don Markstein's Toonopedia. Archived from the original on September 1, 2015. Retrieved January 18, 2007.

- ↑ Coa.inducks.org

- ↑ http://genome.ch.bbc.co.uk/schedules/bbctwo/england/2006-08-27#at-10.00

- ↑ Inge, M. Thomas (September 2012). "Walt Disney's Song of the South and the Politics of Animation". Journal of American Culture. 35 (3): 228. Retrieved July 2, 2016.

- ↑ "Disney (Song of the South)". Urban Legends Reference Pages. Retrieved January 18, 2007.

- ↑ Audio of Robert Iger's statement can be heard here

- ↑ "Disney Backpedaling on Releasing Song of the South?". songofthesouth.net. Retrieved May 28, 2007.

- ↑ "Actually, things are looking pretty good right now for "Song of the South" to finally be released on DVD in late 2008 / early 2009". jimhillmedia.net. Retrieved July 6, 2007.

- ↑ "Disney CEO Calls Movie Antiquated and Fairly Offensive". songofthesouth.net. Retrieved March 16, 2010.

- ↑ "Disney Producer Encouraging About 'Song of the South' Release". The Post-Movie Podcast. November 20, 2010. Retrieved November 16, 2011.

- ↑ Mike Brantley (January 6, 2002). "'Song of the South'". Alabama Mobile Register. Retrieved January 18, 2007.

- ↑ http://www.rogerebert.com/answer-man/movie-answer-man-02132000

- ↑ "Song of the South Memorabilia". Song of the South.net. Archived from the original on February 13, 2007. Retrieved January 18, 2007.

- ↑ "Japanese Court Rules Pre-1953 Movies in Public Domain", contactmusic.com, December 7, 2006.

- ↑ "Song of the South, Laserdisc (Hong Kong)

- ↑ "Intercontinental Video Ltd

- ↑ "AKAs for Song of the South". Retrieved January 18, 2007.

- ↑ "Walt Disney's: helaftens spillefilmer 1941–1981". Archived from the original on May 10, 2011. Retrieved October 3, 2009.

- ↑ Amidi, Amid (July 15, 2017). "In Her First Act As A Disney Legend, Whoopi Goldberg Tells Disney To Stop Hiding Its History". Cartoon Brew. Retrieved August 7, 2017.

- ↑ Thomas, Bob (1994). Walt Disney: An American Original. New York.: Hyperion Books. p. 161. ISBN 0-7868-6027-8.

- ↑ "Top 100 Animated Features of All Time". Online Film Critics Society. Archived from the original on August 27, 2012. Retrieved January 18, 2007.

- ↑ "Song of the South (1946)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved July 19, 2018.

- ↑ Song of the South opened in Los Angeles in 1947, which became its qualification year for the awards.

- ↑ Parsons, Luella (February 28, 1960). "That Little Girl in 'Song of the South' a Big Girl Now". Lincoln Sunday Journal and Star. Retrieved September 2, 2008.

- ↑ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Songs" (PDF). American Film Institute. Retrieved August 13, 2016.

- ↑ "AFI's Greatest Movie Musicals Nominees" (PDF). Retrieved August 13, 2016.

- ↑ Time

- ↑ Jason Sperb, Disney's Most Notorious Film, University of Texas Press (2012), ISBN 0292739745, ISBN 978-0292739741; reviewed in John Lingan, Bristling Dixie, Slate January 4, 2013 (accessed August 21, 2013)

- ↑ Sperb, Disney's Most Notorious Film

- ↑ Jim Hill Media. Wednesdays with Wade: Did the NAACP kill "Song of the South"? November 15, 2005.

- ↑ The New York Times. The Screen; 'Song of the South,' Disney Film Combining Cartoons and Life, Opens at Palace—Abbott and Costello at Loew's Criterion By Bosley Crowther, November 28, 1946.

- ↑ "The New Pictures". Time. November 18, 1946.

- 1 2 Watts, Steven (2001). The Magic Kingdom: Walt Disney and the American Way of Life. University of Missouri Press. pp. 276–277. ISBN 0-8262-1379-0.

- ↑ Jim., Korkis, (2012). Who's afraid of the Song of the South? : and other forbidden Disney stories. Norman, Floyd. Orlando, Fla.: Theme Park Press. ISBN 0984341552. OCLC 823179800.

- ↑ Gevinson, Alan (1997). Within Our Gates: Ethnicity in American Feature Films, 1911-1960. California: University of California Press. p. 956. ISBN 978-0520209640.

- ↑ Sperb, Jason (2010-09-12). "Reassuring Convergence: Online Fandom, Race, and Disney's Notorious Song of the South". Cinema Journal. 49 (4): 25–45. doi:10.1353/cj.2010.0016. ISSN 1527-2087.

- ↑ "Brer Rabbit" at Inducks

Further reading

- Jason Sperb, Disney's Most Notorious Film: Race, Convergence, and the Hidden Histories of Song of the South. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2012.

- Jim Korkis, Who's Afraid of the Song of the South and Other Forbidden Disney Stories. Theme Park Press, 2012.