12 Angry Men (1957 film)

| 12 Angry Men | |

|---|---|

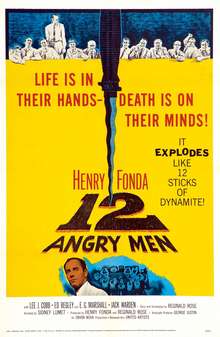

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Sidney Lumet |

| Produced by | |

| Screenplay by | Reginald Rose |

| Story by | Reginald Rose |

| Starring |

|

| Music by | Kenyon Hopkins |

| Cinematography | Boris Kaufman |

| Edited by | Carl Lerner |

Production company |

Orion-Nova Productions |

| Distributed by | United Artists |

Release date |

|

Running time | 96 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $340,000[3][4] |

| Box office | $2,000,000 (rentals)[5] |

12 Angry Men is a 1957 American courtroom drama film adapted from a teleplay of the same name by Reginald Rose.[6][7] Written and co-produced by Rose himself and directed by Sidney Lumet, this trial film tells the story of a jury made up of 12 men as they deliberate the conviction or acquittal of a defendant on the basis of reasonable doubt, forcing the jurors to question their morals and values. In the United States, a verdict in most criminal trials by jury must be unanimous. The film is notable for its almost exclusive use of one set: out of 96 minutes of run time, only three minutes take place outside of the jury room.

12 Angry Men explores many techniques of consensus-building and the difficulties encountered in the process among a group of men whose range of personalities adds intensity and conflict. It also explores the power one person has to elicit change. No names are used in the film; the jury members are identified by number until two members exchange names at the end. The defendant is referred to as "the boy" and the witnesses as "the old man" and "the lady across the street". The film forces the characters and audience to evaluate their own self-image through observing the personality, experiences, and actions of the jurors.

In 2007, the film was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[8] The film was selected as the second-best courtroom drama ever by the American Film Institute during their AFI's 10 Top 10 list[9] and is the highest courtroom drama on Rotten Tomatoes' Top 100 Movies of All Time.[10]

Plot

In a New York City courthouse a jury commences deliberating the case of an 18-year-old Hispanic boy[11] from a slum, on trial for allegedly stabbing his father to death. If there is any reasonable doubt they are to return a verdict of not guilty. If found guilty, the boy will receive a death sentence.

In a preliminary vote, all jurors vote "guilty" except Juror 8, who argues that the boy deserves some deliberation. This irritates some of the other jurors, who are impatient for a quick deliberation, especially Juror 7 who has tickets to the evening's Yankees game, and 10 who demonstrates blatant prejudice against people from slums. Juror 8 questions the accuracy and reliability of the only two witnesses, and the prosecution's claim that the murder weapon, a common switchblade (of which he possesses an identical copy), was "rare". Juror 8 argues that reasonable doubt exists, and that he therefore cannot vote "guilty", but concedes that he has merely hung the jury.

Juror 8 suggests a secret ballot, from which he will abstain, and agrees to change his vote if the others unanimously vote "guilty". The ballot is held and a new "not guilty" vote appears. An angry Juror 3 accuses Juror 5, who grew up in a slum, of changing his vote out of sympathy towards slum children. However, Juror 9 reveals it was he that changed his vote, agreeing there should be some discussion. Juror 8 argues that the noise of a passing train would have obscured the verbal threat that one witness claimed to have heard the boy tell his father "I'm going to kill you". Juror 5 then changes his vote. Juror 11 also changes his vote, believing the boy would not likely have tried to retrieve the murder weapon from the scene if it had been cleaned of fingerprints.

Jurors 5, 6 and 8 question the witness' claim to have seen the defendant fleeing 15 seconds after hearing the father's body hit the floor, since he was physically incapable of reaching an appropriate vantage point in time due to a stroke. An angry Juror 3 shouts that they are losing their chance to "burn" the boy. Juror 8 accuses him of being a sadist. Jurors 2 and 6 then change their votes, tying the vote at 6–6. Shortly after, a thunderstorm begins.

Juror 4 doubts the boy's alibi of being at the movies, because he could not recall it in much detail. Juror 8 tests how well Juror 4 remembers previous days, which he does, with difficulty. Juror 2 questions the likelihood that the boy, who was almost a foot shorter than his father, could have inflicted the downward stab wound found in the body. Jurors 3 and 8 then conduct an experiment to see whether a shorter person could stab downwards on a taller person. The experiment proves the possibility but Juror 5 then steps up and demonstrates the correct way to hold and use a switchblade; revealing that anyone skilled with a switchblade, as the boy would be, would always stab underhanded at an upwards angle against an opponent who was taller than them, as the grip of stabbing downwards would be too awkward and the act of changing hands too time consuming.

Increasingly impatient, Juror 7 changes his vote to hasten the deliberation, which earns him the ire of other jurors (especially 11) for voting frivolously; still he insists, unconvincingly, that he actually thinks the boy is not guilty. Jurors 12 and 1 then change their votes, leaving only three dissenters: Jurors 3, 4 and 10. Juror 10 then vents a torrent of condemnation of slum-born people, claiming they are no better than animals who kill for fun. Most of the others turn their backs to him. When the remaining "guilty" voters are pressed to explain themselves, Juror 4 states that, despite all the previous evidence, the woman from across the street who saw the killing still stands as solid evidence. Juror 12 then reverts his vote, making the vote 8–4.

Juror 9, seeing Juror 4 rub his nose (which is being irritated by his glasses), realizes that the woman who allegedly saw the murder had impressions in the sides of her nose, indicating that she wore glasses, but did not wear them in court out of vanity. Other jurors, most notably Juror 1, confirm that they saw the same thing. Juror 8 adds that she would not have been wearing them while trying to sleep, and points out that on her own evidence the attack happened so swiftly that she wouldn't have had time to put them on. Jurors 12, 10 and 4 then change their vote to "not guilty", leaving only Juror 3. Juror 3 gives a long and increasingly tortured string of arguments, building on earlier remarks that his relationship with his own son is deeply strained, which is ultimately why he wants the boy to be guilty. He finally loses his temper and tears up a photo of him and his son, but suddenly breaks down crying and changes his vote to "not guilty", making the vote unanimous. Outside, Jurors 8 (Davis) and 9 (McCardle) exchange names, and all of the jurors descend the courthouse steps to return to their individual lives.

Cast

The twelve jurors are referred to – and seated – in the order below:

- An assistant high school American football coach. As the jury foreman, he is somewhat preoccupied with his duties, although helpful to accommodate others. He is the ninth to vote "not guilty", never giving the reason for changing his vote; played by Martin Balsam.

- A meek and unpretentious bank worker who is at first dominated by others, but as the climax builds, so does his courage. He is the fifth to vote "not guilty"; played by John Fiedler.

- A businessman and distraught father, opinionated, disrespectful and stubborn with a temper. The main antagonist and most passionate advocate of a guilty verdict throughout the film, due to having a poor relationship with his own son. He is the last to vote "not guilty"; played by Lee J. Cobb.

- A rational, unflappable, self-assured and analytical stock broker who is concerned only with the facts, and is appalled by the bigotry of Juror 10. He is the eleventh to vote "not guilty"; played by E. G. Marshall.

- A man who grew up in a violent slum, and does not take kindly to insults about his upbringing. A Baltimore Orioles fan, he is the third to vote "not guilty"; played by Jack Klugman.

- A house painter, tough, but principled and respectful. He is the sixth to vote "not guilty"; played by Edward Binns.

- A wisecracking salesman and sports fan. He is the seventh to vote "not guilty". Throughout the film it appears that he cares little about the arguments being made; his greatest concern is get to a verdict in time to make it to the evening baseball game; played by Jack Warden.

- An architect and the first to vote "not guilty". He mentions that he has three children. At the end of the film, he reveals to Juror #9 that his name is Davis, one of only two jurors to reveal his name; played by Henry Fonda.

- An observant senior. He is the second to vote "not guilty". At the end of the film, he reveals to Juror #8 that his name is McCardle, one of only two jurors to reveal his name; played by Joseph Sweeney.

- A garage owner; a pushy and loud-mouthed bigot. He is the tenth to vote "not guilty"; played by Ed Begley.

- A European watchmaker and naturalized American citizen who demonstrates strong patriotism. He is polite and makes a point of speaking with proper English grammar. He is the fourth to vote "not guilty"; played by George Voskovec.

- A wisecracking, indecisive advertising executive. He is the only juror to change his vote more than once during deliberations, initially voting "guilty", and changing three times. Ultimately, he is the eighth to settle on voting "not guilty"; played by Robert Webber.

Uncredited

- Rudy Bond as The Judge

- Tom Gorman as Stenographer

- James Kelly as The Bailiff

- Billy Nelson as Court Clerk

- John Savoca as The Accused

- Walter Stocker as Man Waiting for Elevator

Production

Reginald Rose's screenplay for 12 Angry Men was initially produced for television (starring Robert Cummings as Juror 8), and was broadcast live on the CBS program Studio One in September 1954. A complete kinescope of that performance, which had been missing for years and was feared lost, was discovered in 2003. It was staged at Chelsea Studios in New York City.[12]

The success of the television production resulted in a film adaptation. Sidney Lumet, whose prior directorial credits included dramas for television productions such as The Alcoa Hour and Studio One, was recruited by Henry Fonda and Rose to direct. 12 Angry Men was Lumet's first feature film, and the only producing credit for Fonda and Rose. Fonda later stated that he would never again produce a film.

The filming was completed after a short but rigorous rehearsal schedule, in less than three weeks, on a tight budget of $340,000 (equivalent to $2,963,000 in 2017).

At the beginning of the film, the cameras are positioned above eye level and mounted with wide-angle lenses, to give the appearance of greater depth between subjects, but as the film progresses the focal length of the lenses is gradually increased. By the end of the film, nearly everyone is shown in closeup, using telephoto lenses from a lower angle, which decreases or "shortens" depth of field. Lumet stated that his intention in using these techniques with cinematographer Boris Kaufman was to create a nearly palpable claustrophobia.[13]

Reception

Initial response

On its first release, 12 Angry Men received critical acclaim. A. H. Weiler of The New York Times wrote, "It makes for taut, absorbing, and compelling drama that reaches far beyond the close confines of its jury room setting." His observation of the twelve men was that "their dramas are powerful and provocative enough to keep a viewer spellbound."[14] Variety called it an "absorbing drama" with acting that was "perhaps the best seen recently in any single film,"[15] Philip K. Scheuer of the Los Angeles Times declared it a "tour de force in movie making,"[16] The Monthly Film Bulletin deemed it "a compelling and outstandingly well handled drama,"[17] and John McCarten of The New Yorker called it "a fairly substantial addition to the celluloid landscape."[18]

However, the film was a box office disappointment.[19][20] The advent of color and widescreen productions may have contributed to its disappointing box office performance.[19] It was not until its first airing on television that the movie finally found its audience.[21]

Legacy

The film is viewed as a classic, highly regarded from both a critical and popular viewpoint: Roger Ebert listed it as one of his "Great Movies".[22] The American Film Institute named Juror 8, played by Henry Fonda, 28th in a list of the 50 greatest movie heroes of the 20th century. AFI also named 12 Angry Men the 42nd most inspiring film, the 88th most heart-pounding film and the 87th best film of the past hundred years. The film was also nominated for the 100 movies list in 1998.[23] As of March 2017, the film holds a 100% approval rating on the review aggregate website Rotten Tomatoes.[24] In 2011, the film was the second most screened film in secondary schools in the United Kingdom.[25]

American Film Institute lists:

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies – Nominated

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Thrills – No. 88

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes & Villains: Juror No. 8 – No. 28 Hero

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Cheers – No. 42

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition) – No. 87

- AFI's 10 Top 10 – No. 2 Courtroom Drama

Awards

The film was nominated for Academy Awards in the categories of Best Director, Best Picture, and Best Writing of Adapted Screenplay. It lost to The Bridge on the River Kwai in all three categories. At the 7th Berlin International Film Festival, the film won the Golden Bear Award.[26]

Cultural influences

Speaking at a screening of the film during the 2010 Fordham University Law School Film festival, Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor stated that seeing 12 Angry Men while she was in college influenced her decision to pursue a career in law. She was particularly inspired by immigrant Juror 11's monologue on his reverence for the American justice system. She also told the audience of law students that, as a lower-court judge, she would sometimes instruct juries to not follow the film's example, because most of the jurors' conclusions are based on speculation, not fact.[27] Sotomayor noted that events such as Juror 8 entering a similar knife into the proceeding; performing outside research into the case matter in the first place; and ultimately the jury as a whole making broad, wide-ranging assumptions far beyond the scope of reasonable doubt (such as the inferences regarding the woman wearing glasses) would not be allowed in a real life jury situation, and would in fact have yielded a mistrial[28] (assuming, of course, that applicable law permitted the content of jury deliberations to be revealed).

The movie has had a number of adaptations. A 1963 German TV production ("Die Zwölf Geschworenen") was directed by Günter Gräwert, while a 1991 homage by Kōki Mitani, Juninin no Yasashii Nihonjin ("12 gentle Japanese"), posits a Japan with a jury system and features a group of Japanese people grappling with their responsibility in the face of Japanese cultural norms. The 1987 Indian film Ek Ruka Hua Faisla ("a pending decision") is a remake of the film, with an almost identical storyline. Russian director Nikita Mikhalkov also made a 2007 adaptation, 12. A 2015 Chinese adaptation, "12 Citizens", follows the plot of the original 1957 American movie, while including characters reflecting contemporary Beijing society, including a cab driver, guard, businessman, policeman, a retiree persecuted in a 1950s' political movement, and others.[29] The detective drama television show Veronica Mars, which like the film includes the theme of class issues, featured an episode, "One Angry Veronica", in which the title character is selected for jury duty. The episode flips the film's format and depicts one holdout convincing the jury to convict the privileged defendants of assault against a less well-off victim, despite their lawyers initially convincing 11 jury members of a not guilty verdict.

In 1997, a television remake of the film under the same title was directed by William Friedkin and produced by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. In the newer version, the judge is a woman and four of the jurors are Black, but the overall plot remains intact. Modernizations include not smoking in the jury room, changes in references to pop culture figures and income, references to execution by lethal injection as opposed to the electric chair, more race-related dialogue and profanity.

The film has also been subject to parody. In 2015, the Comedy Central TV series Inside Amy Schumer aired a half-hour parody of the film titled "12 Angry Men Inside Amy Schumer".[30][31] BBC Radio comedy Hancock's Half Hour, starring Tony Hancock and Sid James, and written by Ray Galton and Alan Simpson, broadcast a half-hour parody on October 16, 1959, also known as Twelve Angry Men. The Flintstones story "Disorder in the Court" and The Simpsons story "The Boy Who Knew Too Much" similarly feature the respective patriarchs of both families playing holdout jurors. Family Guy paid tribute to the film with its Season 11 episode titled "12 and a Half Angry Men", and King of The Hill acknowledged the film with their parody "Nine Pretty Darn Angry Men" in season 3. Sitcom Happy Days also features a similar story in the season 5 episode "Fonzie for the Defense", when Howard Cunningham and Fonzie are picked for a jury, and Fonzie is the lone hold-out for innocence, swaying the rest of the jury.[32] Saturday Night Live parodied the film in 1984 in a sketch called First Draft Theater. The American TV situation comedy, The Odd Couple, starring Jack Klugman (juror 5 in the movie), satirizes the film in "The Jury Story".

See also

- List of American films of 1957

- 12 Angry Men (1997 film)

- Twelve Angry Men

- List of films with a 100% rating on Rotten Tomatoes, a film review aggregator website

References

- ↑ "12 Angry Men – Details". AFI Catalog of Feature Films. Retrieved July 8, 2018.

- ↑ "New Acting Trio Gains Prominence". Los Angeles Times. April 9, 1957. p. 23.

- ↑ Box Office Information for 12 Angry Men. The Numbers. Retrieved April 14, 2012.

- ↑ Anita Ekberg Chosen for 'Mimi' Role Louella Parsons:. The Washington Post and Times Herald (1954–1959) [Washington, D.C] 08 Apr 1957: A18.

- ↑ "Top Grosses of 1957", Variety, 8 January 1958: 30

- ↑ Variety film review; February 27, 1957, p. 6.

- ↑ Harrison's Reports film review; March 2, 1957, page 35.

- ↑ "National Film Registry". National Film Registry (National Film Preservation Board, Library of Congress). September 12, 2011. Archived from the original on April 19, 2012. Retrieved November 28, 2011.

- ↑ "AFI's 10 Top 10 Courtroom Drama". American Film Institute. 2008-06-17. Retrieved 2014-11-29.

- ↑ "Top 100 Movies of All Time". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 2014-11-29.

- ↑ http://www.umass.edu/legal/Hilbink/250/12Angry.pdf, see page 8 of PDF

- ↑ Alleman, Richard (February 1, 2005). New York: The Movie Lover's Guide: The Ultimate Insider Tour of Movie New York. Broadway Books. p. 231. ISBN 978-0-7679-1634-9.

- ↑ "Evolution of TWELVE ANGRY MEN". Playhouse Square. Archived from the original on January 6, 2009. Retrieved September 11, 2008.

- ↑ Weiler, A.H. (April 15, 1957). "Twelve Angry Men (1957) Movie Review". The New York Times. Retrieved August 28, 2011.

- ↑ "12 Angry Men". Variety. February 27, 1957. p. 6.

- ↑ Scheuer, Philip K. (April 11, 1957). "Audience Sweats It Out—Literally—With Jury". Los Angeles Times. Part II, p. 13.

- ↑ "Twelve Angry Men". The Monthly Film Bulletin. Vol. 24 no. 281. June 1957. p. 68.

- ↑ McCarten, John (April 27, 1957). "The Current Cinema". The New Yorker. p. 66.

- 1 2 12 Angry Men Filmsite Movie Review. AMC FilmSite. Retrieved April 14, 2012.

- ↑ 12 Angry Men at AllMovie. Rovi. Retrieved April 14, 2012.

- ↑ Beyond a Reasonable Doubt: Making 12 Angry Men Featurette on Collector's Edition DVD

- ↑ "12 Angry Men Movie Reviews, Pictures". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on September 13, 2010. Retrieved August 17, 2010.

- ↑ "America's Greatest Movies" (PDF). American Film Institute. 2002. Retrieved 2015-08-23.

- ↑ "12 Angry Men Movie Reviews, Pictures". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on February 28, 2009. Retrieved August 6, 2010.

- ↑ "Top movies for schools revealed". BBC News. December 13, 2011. Retrieved January 4, 2012.

- ↑ "7th Berlin International Film Festival: Prize Winners". berlinale.de. Retrieved December 28, 2009.

- ↑ Semple, Kirk (October 18, 2010), "The Movie That Made a Supreme Court Justice", The New York Times, retrieved October 18, 2010

- ↑ "Jury Admonitions In Preliminary Instructions (Revised May 5, 2009)1" (PDF). Retrieved June 23, 2011.

- ↑ Young, Deborah (2015-06-23). "'12 Citizens' Shanghai Review". Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 2015-08-23.

- ↑ Lyons, Margaret. "Behold Inside Amy Schumer's Dead-On 12 Angry Men". Vulture. Retrieved May 6, 2015.

- ↑ Homes, Linda. "Amy Schumer Puts Her Own Looks On Trial". NPR. Retrieved May 6, 2015.

- ↑ ""Happy Days" Fonzie for the Defense (TV Episode 1978)". IMDb.

Further reading

- Making Movies, by Sidney Lumet. (c) 1995, ISBN 978-0-679-75660-6

- Ellsworth, Phoebe C. (2003). "One Inspiring Jury [Review of 'Twelve Angry Men']". Michigan Law Review. 101 (6): 1387–1407. JSTOR 3595316. In depth analysis compared with research on actual jury behaviour.

- The New York Times, April 15, 1957, "12 Angry Men", review by A. H. Weiler

- Readings on Twelve Angry Men, by Russ Munyan, Greenhaven Press, 2000, ISBN 978-0-7377-0313-9

- Chandler, David. "The Transmission model of communication" Communication as Perspective Theory. Sage publications. Ohio University, 2005.

- Lanham, Richard. Introduction: The Domain of Style analyzing prose. (New York, NY: Continuum, 2003)

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: 12 Angry Men |