Chappaquiddick incident

| |

| Date | July 18, 1969 |

|---|---|

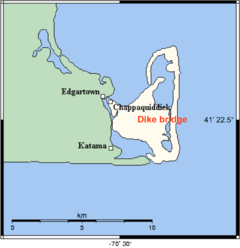

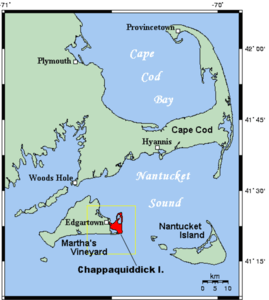

| Location | Chappaquiddick Island, Massachusetts |

| Outcome | Ted Kennedy pleaded guilty to a charge of leaving the scene of the crash causing personal injury; declined to campaign for President in 1972 and 1976.[1][2][3] |

| Deaths | Mary Jo Kopechne |

The Chappaquiddick incident was a single-vehicle car accident that occurred on Chappaquiddick Island, Massachusetts, on Friday, July 18, 1969.[4][5] The late night accident was caused by Senator Ted Kennedy's negligence, and resulted in the death of his 28-year-old passenger, Mary Jo Kopechne, who was trapped inside the vehicle.[6][7][8][9]

According to his testimony, Kennedy accidentally drove[10] his car off the one-lane bridge and into the tide-swept Poucha Pond. He swam free, left the scene, and did not report the accident to the police for ten hours; Kopechne died inside the fully submerged car.[11][12] The next day, the car with Kopechne's body inside was recovered by a diver, minutes before Kennedy reported the accident to local authorities. Kennedy pleaded guilty to a charge of leaving the scene of a crash causing personal injury, and later received a two-month suspended jail sentence.

The Chappaquiddick incident became a nationally known scandal, while occurring during the Apollo 11 moon landing, and likely influenced Kennedy's decision not to campaign for President in 1972 and 1976.[7][8][9] Furthermore, the incident was said to have undermined Kennedy's chances of ever becoming President.[13]

Background

On the evening of July 18, 1969, U.S. Senator from Massachusetts Ted Kennedy hosted a party at a rented cottage secluded on Chappaquiddick Island, which is accessible via ferry from the town of Edgartown on the nearby larger island, Martha's Vineyard.[14] The gathering, at the cottage of Sidney Lawrence (41°22′27″N 70°28′15″W / 41.3742°N 70.4707°W), was a reunion for a group of six single women all in their twenties that included Rosemary Keough, Esther Newberg, sisters Nance Lyons and Mary Ellen Lyons, Susan Tannenbaum, and Mary Jo Kopechne. The group (the only women invited to the party) were known as the Boiler Room Girls,[15] and they had served on Robert F. Kennedy's 1968 presidential campaign. Present at the party were six older men, including co-hosts Kennedy and his cousin Joseph Gargan[Notes 1], as well as Paul F. Markham, Charles Tretter, and Raymond LaRosa. Markham was a school friend of Gargan's who had previously served as the U.S. Attorney for Massachusetts.[17] Attorney Charles Tretter was a Kennedy advisor, Raymond La Rosa had known Kennedy for about 8 or 10 years and had diving experience. Kennedy's 63-year-old chauffeur, John B. Crimmins[18] (Kennedy's part-time driver), also attended the party.[7] All but one of the men (Crimmins) were married, and all six women were single and 28 or younger.[7]

That weekend, Ted Kennedy was also competing in the Edgartown Yacht Club Regatta, a sailing competition that was taking place over several days.

During the inquest into Kopechne's death, Kennedy testified that he left the party at "approximately 11:15 p.m."[19] When he announced that he was about to leave, he claimed Mary Jo told him "that she was desirous of leaving, [and asked] if I would be kind enough to drop her back at her hotel." Kennedy then requested the keys to his car (which he did not usually drive) from his chauffeur, Crimmins. Asked why he did not have his chauffeur drive them both, Kennedy explained that Crimmins and some other guests "were concluding their meal, enjoying the fellowship and it didn't appear to be necessary to require him to bring me back to Edgartown."[20] Mary Jo told no one that she was leaving for the night with Kennedy, and in fact she left her purse and hotel key at the party.[21]

Timeline of events

Part-time Deputy Sheriff Christopher "Huck" Look was working that night, as a special duty officer at the Edgartown Yacht Club Regatta dance held on the main island of Martha's Vineyard until 30 minutes after midnight. According to Deputy Look and several independent witnesses, Look left the dance after midnight (now into the next day of July 19) between 12:25 am and 12:30 am, crossed over to Chappaquiddick Island in the yacht club's private boat (because the public ferry closed down at midnight), got into his personal car parked near the boat landing, and drove easterly onto Chappaquiddick Road toward his home (Kennedy would refer to Chappaquiddick Road as Main Street in his statement to police).

Look testified that at around 12:40 am (still driving easterly on Chappaquiddick Road) he was approaching the 90-degree right hand turn of Chappaquiddick Road (a paved road with a solid white line painted down the middle), which turn would then continue him in a southerly direction on the same paved road toward his home. At that 90-degree turn Chappaquiddick Road intersected with two unpaved roads. One road was called Dike or Dyke Road (a dirt, sand and gravel road that ran away easterly toward the dunes, a small beach, and Dike/Dyke Bridge); the second road was then known as Cemetery Road (a dirt, sand and gravel private driveway that ran northerly and is now known as Willett Lane). As Look approached the turn he noticed the headlights of a car coming toward him traveling northerly on Chappaquiddick Road. The other car reached the 90-degree turn in the road before Look got there. As it did, the dark four-door car then passed slowly in front of Look and his headlights shone directly into the passenger compartment. Look could clearly see a man driving and a woman in the front seat. The time was unquestionably about 12:40 am, give or take a minute or two. The car then failed to follow the paved road and instead drove straight off the pavement and onto Cemetery Road, where it stopped. Look made a right turn continuing on Chappaquiddick Road and looked in his rear-view mirror. Thinking the occupants of the car might be lost, Look stopped, got out of his car and walked towards the other vehicle in full deputy sheriff uniform. When he was 25 to 30 ft (7.6 to 9.1 m) away, the car reversed and started backing up towards him. Look called out to offer his help. The car then moved forward and veered quickly eastward onto Dike Road, speeding away and leaving a cloud of dust.[22] Look recalled that the car's license plate began with an "L" and contained two "7"'s, both details true of Kennedy's license plate on Kennedy's black four-door Oldsmobile Delmont 88.[7] Look knew the island well and that meant he knew that the car was headed to a dead end at Dike Bridge and the sand dunes impassable to non-four-wheel-drive vehicles that lay beyond it. However, Look returned to his car and continued on his way south.

Deputy Look recounted the next morning to Edgartown Police that he believed that the car he saw at 12:40 am was in fact the same car that the police found in the water off Dike Bridge containing Kopechne's body.

Back on Chappaquiddick Road, a short distance up the road from where Look spotted the car speeding away toward Dike bridge at 12:40 am, Look saw two women (later identified as Kennedy party guests Nance Lyons and Mary Ellen Lyons) and a man (party guest Ray LaRosa) doing what one might call a "conga line" dance down the middle of the road. Look stopped again to ask if they needed a lift. One of the Lyons sisters said "Shove off, buddy," after which LaRosa stated to the uniformed deputy apologetically "Thank you, no. We're just going over there to our house" (pointing to the cottage rented by Kennedy). Ray LaRosa and the Lyons women corroborated Look's testimony about meeting Deputy Look in the road and the verbal exchange, but they were rather vague about the time. Look, however, was not. Look knew the time was unquestionably 12:40 am or a minute or so after he spotted the Oldsmobile. LaRosa did testify that he clearly remembered encountering another car passing him and the two women that night as they danced or walked in the road. That car passed them moments before they encountered Deputy Look. The car came from the direction of the Kennedy party (the rented cottage), and it slowly passed LaRosa and the Lyons girls as it went by and appeared to be headed in the direction from which Look would be coming. However, even though LaRosa should have been familiar with Kennedy's car, LaRosa would not positively identify the vehicle that passed him as Kennedy's Oldsmobile, nor could he describe the car in any type of detail.

Meanwhile, according to Kennedy's inquest testimony, he left the party with Kopechne at about 11:15 pm and immediately drove northerly on Chappaquiddick Road (Kennedy called it Main Street) as he drove to the ferry landing. Kennedy claimed that at some point (which should have been only minutes later) he made a very wrong turn onto Dike Road (obviously when he reached the intersections of Chappaquiddick, Dike and Cemetery Roads). Kennedy claimed at the inquest while under oath that he never stopped on Cemetery Road, never backed up, never saw the deputy, and never saw another car or person after he left the cottage with Kopechne. Kennedy further claimed that after he turned onto Dike Road, he was driving at "approximately twenty miles an hour [32 km/h]"[23] and did not realize that he was no longer headed west toward the ferry landing, but instead east toward a barrier beach.

Dike Bridge (41°22′24″N 70°27′13″W / 41.3734°N 70.4536°W),[24] connecting Tom's Neck Point[25] and Cape Poge to Chappaquiddick Island, was a wooden structure that, at the time, was not protected by a guardrail and was angled obliquely to the road.[26] A fraction of a second before he reached the bridge, Kennedy applied his brakes and then drove over the south edge of the bridge. The car plunged into tide-swept Poucha Pond[27][28][29] (there is a channel) and came to rest, upside down, underwater. Kennedy later stated that he was able to swim free of the vehicle, but Kopechne was not. At the inquest, Kennedy claimed that he called Kopechne's name several times from the shore and tried to swim down to reach her seven or eight times. Knowing the woman was still trapped inside the vehicle, Kennedy rested on the bank for around 15 minutes before he returned on foot to Lawrence Cottage, the site of the party attended by Kopechne and the other "Boiler Room Girls". Kennedy denied seeing any house with a light on during his walk back to Lawrence Cottage.[30]

According to one commenter, Kennedy's foot route back to Lawrence Cottage would have taken him past four houses from which he could have telephoned to summon help before he reached the cottage. He did not, however, attempt to contact the local residents.[31] The first of the houses, referred to as "Dike House", was 150 yards (140 m) away from the bridge and occupied by Sylvia Malm and her family at the time of the incident. Malm stated later that she was home, she had a phone and she had left a light on at the residence when she retired that evening.[32]

According to Kennedy's further testimony, when he returned to the rented cottage (where the party was still in swing) he did not alert all of the party attendees of the accident. Instead he collapsed in the back seat of a rented car parked in the driveway and quietly summoned Joe Gargan and Paul Markham. After a brief hushed conversation with Gargan and Markham outside the cottage, the three men rushed to the waterway and Kennedy's overturned car to try to rescue Kopechne. Both Gargan and Markham claimed they tried multiple times to dive into the water to rescue Kopechne.[15] Kennedy testified that their efforts to rescue Kopechne failed, and Gargan and Markham drove him to the ferry landing. While standing next to a public phone booth at the landing, Gargan, Markham and Kennedy (all three of them lawyers) discussed what they should do. Gargan and Paul Markham insisted multiple times that the crash had to be reported to the authorities.[33] According to Markham's testimony, Kennedy was sobbing and on the verge of becoming crazed.[34] Kennedy would testify, "[I] had full intention of reporting it [the accident]. And I mentioned to Gargan and Markham something like, 'You take care of the other girls; I will take care of the accident!'—that is what I said and I dove into the water."[33] Kennedy had already told Gargan and Markham not to tell the other women anything about the incident "[b]ecause I felt strongly that if these girls were notified that an accident had taken place and Mary Jo had, in fact, drowned, that it would only be a matter of seconds before all of those girls, who were long and dear friends of Mary Jo's, would go to the scene of the accident and enter the water with, I felt, a good chance that some serious mishap might have occurred to any one of them."[35]

Gargan and Markham later testified that they assumed that Kennedy was going to inform the authorities about the accident once he got back to Edgartown, and so they did not do the reporting themselves.[17] According to Kennedy's testimony, after he dove in the water near the ferry landing he swam across the 500-foot (150 m) channel, back to Edgartown, and instead of reporting the accident he returned to his hotel room, where he removed his clothes and collapsed on his bed.[35] Hearing noises, he later put on dry clothes, left his room and asked someone what the time was: it was something like 2:30 a.m., the senator recalled.

Meanwhile, Gargan and Markham had already driven the rental car back to the cottage, where at about 2:00 am they entered the cottage and told no one what had happened. When asked where Kennedy and Kopechne were, they said that Kennedy swam back to Edgartown and Kopechne was probably at her hotel. When questioned further they told everyone to get some sleep.

Kennedy testified that he was back at the hotel, and as the night went on, "I almost tossed and turned and walked around that room ... I had not given up hope all night long that, by some miracle, Mary Jo would have escaped from the car."[36] Kennedy complained at 2:55 a.m. to the hotel owner that he had been awakened by a noisy party.[17]

By 7:30 a.m., Kennedy was talking "casually" to the winner of the previous day's sailing race and gave no indication that anything was amiss.[17] At 8:00 a.m., Gargan and Markham found Kennedy at his hotel where they had a "heated conversation" in Kennedy's room. According to Kennedy's testimony, the two men asked why he had not reported the accident. Kennedy responded by telling them "about my own thoughts and feelings as I swam across that channel ... that somehow when they arrived in the morning that they were going to say that Mary Jo was still alive."[36]

Crisis management

The three men subsequently crossed back to Chappaquiddick Island on the ferry, where Kennedy made a series of telephone calls from a pay telephone near the ferry crossing (the same pay phone that the three men had stood by approximately 6 hours earlier at 2:00 a.m. discussing Kennedy's options). Instead of notifying the authorities that he was the operator of the vehicle that was probably still upside down near Dike bridge, Kennedy made phone calls to friends and lawyers for advice.

Kennedy called Helga Wagner,[37] John Tunney[38] and others that morning after his car had gone into Poucha Pond. Even after the calls, Kennedy still did not report the crash to authorities.[17]

Robert McNamara, Ted Sorensen, Richard N. Goodwin, Lem Billings, Milton Gwirtzman, David W. Burke, John Culver, John Tunney,[38] Stephen Edward Smith, Joseph F. Gargan,[39] Paul E. Markham and others would be summoned and would arrive to advise Kennedy.[40][41]

Recovery of Kopechne's body and Kennedy's statement

A short time after 8:00 am, a fisherman and his young son saw Kennedy's submerged car, with Kopechne still inside, in the water and notified the residents of the cottage nearest the scene, who called the authorities at about 8:20 a.m.[42]

Edgartown Police Chief James Arena arrived at the scene about 10 or 15 minutes later.[43] After attempting unsuccessfully to examine the interior of the submerged vehicle,[43][44] Arena summoned a commercial diver along with equipment capable of towing or winching the vehicle out of the water.[45] Diver John Farrar, the captain of the Edgartown Fire Rescue unit, arrived at 8:45 a.m. equipped with scuba gear and discovered Kopechne's body; he extricated it from the vehicle within 10 minutes.[46][47] Police checked the car's license plate and saw that it was registered to Kennedy.[15] Meanwhile, Kennedy was still at the pay phone by the ferry crossing when he heard that his car and Kopechne's body had been discovered;[48] Kennedy then crossed back to Edgartown and went to the police station. Gargan simultaneously went to where the "Boiler Room Girls" were staying to inform them about the incident.[17]

Kennedy entered the police station in Edgartown at 10:00 am, made a couple more telephone calls, and then dictated a statement to his aide Paul Markham, which Markham hand wrote, which was then given to the police. The statement simply read:

On July 18, 1969, at approximately 11:15 p.m. in Chappaquiddick, Martha's Vineyard, Massachusetts, I was driving my car on Main Street on my way to get the ferry back to Edgartown. I was unfamiliar with the road and turned right onto Dike Road, instead of bearing hard left on Main Street. After proceeding for approximately one-half mile [800 m] on Dike Road I descended a hill and came upon a narrow bridge. The car went off the side of the bridge. There was one passenger with me, one Miss Mary [Kopechne],[49] a former secretary of my brother Sen. Robert Kennedy. The car turned over and sank into the water and landed with the roof resting on the bottom. I attempted to open the door and the window of the car but have no recollection of how I got out of the car. I came to the surface and then repeatedly dove down to the car in an attempt to see if the passenger was still in the car. I was unsuccessful in the attempt. I was exhausted and in a state of shock. I recall walking back to where my friends were eating. There was a car parked in front of the cottage and I climbed into the backseat. I then asked for someone to bring me back to Edgartown. I remember walking around for a period and then going back to my hotel room. When I fully realized what had happened this morning, I immediately contacted the police.[50]

Court appearance

On July 25—seven days after the incident—Kennedy pleaded guilty to a charge of leaving the scene of an accident causing bodily injury. Kennedy's attorneys suggested that any jail sentence should be suspended, and the prosecutors agreed by citing Kennedy's age (he was 37 years old at the time of the incident), character, and prior reputation.[51] Judge James Boyle sentenced Kennedy to two months' incarceration, the statutory minimum for the offense, which he suspended.

In announcing the sentence, Boyle referred to Kennedy's "unblemished record" and said that he "has already been, and will continue to be punished far beyond anything this court can impose."[52]

Kennedy's televised statement

At 7:30 that evening, Kennedy made a lengthy prepared statement about the incident that was broadcast live by the television networks.[53][54] Among other things, he said:[55]

- "Only reasons of health" had prevented his wife from accompanying him to the regatta.

- There was "no truth whatever to the widely circulated suspicions of immoral conduct" regarding the behavior of Kennedy and Kopechne that evening.

- He "was not driving under the influence of liquor."

- His conduct during the hours immediately after the accident "made no sense to [him] at all."

- His doctors had informed him that he had suffered cerebral concussion and shock, but he did not seek to use his medical condition to escape responsibility for his actions.

- He "regard[ed] as indefensible the fact that [he] did not report the accident to the police immediately."

- Instead of notifying the authorities immediately, he "requested the help of two friends, Joe Gargan and Paul Markham, and directed them to return immediately to the scene with [him] (it then being sometime after midnight) in order to undertake a new effort to dive down and locate Miss Kopechne."

- "All kinds of scrambled thoughts" went through his mind after the accident, including "whether the girl might still be alive somewhere out of that immediate area ... , whether some awful curse actually did hang over all the Kennedys ... whether there was some justifiable reason for [him] to doubt what had happened and to delay [his] report"... whether somehow the awful weight of this incredible incident might in some way pass from [his] shoulders."

- He was overcome "by a jumble of emotions—grief, fear, doubt, exhaustion, panic, confusion and shock."

- Having instructed Gargan and Markham "not to alarm Mary Jo's friends that night," Kennedy returned to the ferry with the two men and then "suddenly jumped into the water and impulsively swam across, nearly drowning once again in the effort, returning to [his] hotel around 2 a.m. and collapsed in [his] room."

Kennedy then asked the people of Massachusetts to decide whether he should resign:

If at any time, the citizens of Massachusetts should lack confidence in their Senator's character or his ability, with or without justification, he could not in my opinion adequately perform his duties, and should not continue in office. The opportunity to work with you and serve Massachusetts has made my life worthwhile. So I ask you tonight, the people of Massachusetts, to think this through with me. In facing this decision, I seek your advice and opinion. In making it I seek your prayers. For this is a decision that I will have finally to make on my own.[19]

He concluded by quoting a passage from a book by his brother John, Profiles in Courage.[56]

Testimony and cause of death

John Farrar[57] was the captain of the Edgartown Fire Rescue unit and the diver who recovered Kopechne's body. He alleged that Kopechne died from suffocation rather than from drowning or from the impact of the overturned vehicle. This hypothesis was based upon the posture in which he found the body and the body's relative position to the area of an ultimate air pocket in the overturned vehicle. Farrar also asserted that Kopechne would have probably survived if a more timely rescue attempt had been conducted.[58][59][60] Farrar located Kopechne's body in the well of the backseat of the overturned submerged car. Rigor mortis was apparent, her hands were clasping the backseat, and her face was turned upward.[61] Farrar testified at the Inquest:

It looked as if she were holding herself up to get a last breath of air. It was a consciously assumed position ... She didn't drown. She died of suffocation in her own air void. It took her at least three or four hours to die. I could have had her out of that car twenty-five minutes after I got the call. But he [Ted Kennedy] didn't call.

— diver John Farrar, Inquest into the Death of Mary Jo Kopechne, Commonwealth of Massachusetts, Edgartown District Court. New York: EVR Productions, 1970.

Later at the inquest, Farrar testified that Kopechne's body was pressed up in the car in the spot where an air bubble would have formed. He interpreted that to mean that Kopechne had survived in the air bubble after the crash, and he concluded that

Had I received a call within five to ten minutes of the accident occurring, and was able, as I was the following morning, to be at the victim's side within twenty-five minutes of receiving the call, in such event there is a strong possibility that she would have been alive on removal from the submerged car.[31]

Farrar believed that Kopechne "lived for at least two hours down there."[62]

The victim wore a blouse, bra, and slacks, but no panties.[63] The medical examiner, Dr. Donald Mills, was satisfied that the cause of death was accidental drowning. He signed a death certificate to that effect and released Kopechne's body to her family without ordering an autopsy; the funeral was on Tuesday, July 22, in Plymouth, Pennsylvania.[64][65][66] Later, on September 18, District Attorney Edmund Dinis attempted to secure an exhumation of Kopechne's body to perform a belated autopsy,[67] citing blood found on Kopechne's long-sleeved blouse and in her mouth and nose, "which may or may not be consistent with death by drowning."[68] The reported discovery of the blood was made when her clothes were given to authorities by the funeral director.[69]

Judge Bernard Brominski, of the Court of Common Pleas of Luzerne County, Pennsylvania, had a hearing on the request on October 20–21.[67] The request was opposed by Kopechne's parents.[67] Forensic pathologist Werner Spitz testified on behalf of Joseph and Gwen Kopechne that the autopsy was unnecessary and the available evidence was sufficient to conclude that Kopechne died from drowning.[70][71] Eventually, Judge Brominski ruled against the exhumation on December 10, saying that there was "no evidence" that "anything other than drowning had caused the death of Mary Jo Kopechne."[72]

Inquest

The inquest[73][40] into Kopechne's death convened in Edgartown in January 1970. At the request of Kennedy's lawyers, the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court ordered it to be performed secretly.[74][75] The 763-page transcript of the inquest was released four months later.[75] Judge James A. Boyle presided at the inquest. The following conclusions were released in his inquest report:[76]

- The accident occurred "between 11:30 p.m. on July 18 and 1:00 a.m. on July 19."

- "Kopechne and Kennedy did not intend to drive to the ferry slip and his turn onto Dike Road had been intentional."

- "A speed of twenty miles per hour as Kennedy testified to operating the car as large as his Oldsmobile would be at least negligent and possibly reckless."

- "For some reason not apparent from [Kennedy's] testimony, he failed to exercise due care as he approached the bridge."

- "There is probable cause to believe that Edward M. Kennedy operated his motor vehicle negligently ... and that such operation appears to have contributed to the death of Mary Jo Kopechne."

Under Massachusetts law, Boyle found "probable cause" that Kennedy had committed a crime and could have issued a warrant for his arrest, but he did not do so.[77] Despite Boyle's conclusions, Dinis chose not to prosecute Kennedy for manslaughter.

The Kopechne family did not bring any legal action against Kennedy but did receive a payment of $90,904 from him personally and $50,000 from his insurance company.[8][78] The Kopechnes later explained their decision not to take legal action by saying, "We figured that people would think we were looking for blood money."[78]

Grand jury

On April 6, 1970, a Dukes County grand jury assembled in special session to investigate Kopechne's death. Judge Wilfred Paquet instructed the members of the grand jury that they could consider only matters brought to their attention by the superior court, the district attorney, or their personal knowledge.[79] Citing the orders of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, Paquet told the grand jury that it could not see the evidence or Boyle's report from the inquest, which were still impounded.[79] Dinis, who had attended the inquest and seen Boyle's report, told the grand jury that there was not enough evidence to indict Kennedy on potential charges of manslaughter, perjury or driving to endanger.[79] The grand jury called four witnesses who had not testified at the inquest: they testified for a total of 20 minutes, but no indictments were issued.[79]

Fatal accident hearing

On July 23, 1969, the registrar of the Massachusetts Registry of Motor Vehicles informed Kennedy that his license would be suspended until a statutory hearing could be held concerning the accident.[80] The suspension was required by Massachusetts law for any fatal motor accident if there were no witnesses. The in camera hearing was held May 18, 1970. It found that "operation was too fast for existing conditions." On May 27, the registrar informed Kennedy in a letter that "I am unable to find that the fatal accident in which a motor vehicle operated by you was involved, was without serious fault on your part" and so his driver's license was suspended for a further six months.[81]

Joan Kennedy miscarriage

Kennedy's wife Joan was pregnant at the time of the incident. Though she was confined to bed because of two previous miscarriages, she attended the funeral of Kopechne and stood beside Ted in court three days later.[82] Soon thereafter, she suffered a third miscarriage,[83] which she blamed on the Chappaquiddick incident.[84]

Other interpretations of evidence

A BBC Inside Story episode, "Chappaquiddick," broadcast on the 25th anniversary of Kopechne's death, advanced a theory that Kennedy and Kopechne had left the party in Kennedy's car, but when Kennedy saw an off-duty policeman in his patrol car, he got out of the car, fearing the political consequences of being discovered by the police late at night with an attractive woman. According to the theory, Kennedy then returned to the party, and Kopechne, unfamiliar both with the large car and the local area, drove the wrong way and crashed off the bridge. The episode argued that the explanation would account for Kennedy's lack of concern the next morning, as he was unaware of the crash, and for the forensic evidence of the injuries to Kopechne being inconsistent with her sitting in the passenger seat.[85]

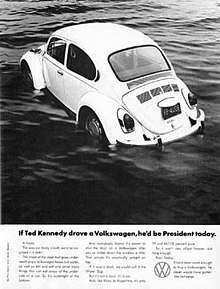

Writer Jack Olsen had earlier advanced a similar theory in his book The Bridge at Chappaquiddick, published early in 1970. Olsen's book was the first full-length examination of the case. Olsen wrote that Kopechne's shorter height (she was 5 ft 2 in (1.57 m), a foot (30 cm) shorter than Kennedy) could have accounted for her possibly not even seeing the bridge, as she drove Kennedy's car over unfamiliar roads, at night, with no external lighting, after she had consumed several alcoholic drinks at the party both had attended. Olsen wrote that Kopechne normally drove a smaller Volkswagen model car, which was much lighter and easier to handle than Kennedy's larger Oldsmobile.[45]

Legacy

The case evoked much satire of Kennedy. For example, Time reported immediately after the incident that "One sick joke already visualizes a Democrat asking about Nixon during the 1972 presidential campaign: "Would you let this man sell you a used car?" Answer: "Yes, but I sure wouldn't let that Teddy drive it."[86] A mock advertisement in National Lampoon magazine showed a floating Volkswagen Beetle—a parody of a well-known Volkswagen advertisement showing that the vehicle's underside was so well sealed that it would float on water—with the remark that Kennedy would have been elected president had he been driving a Beetle that night; the satire resulted in legal action by Volkswagen, claiming unauthorized use of its trademark.[87][88]

Following his televised speech on July 25 regarding the incident,[54] supporters responded with telephone calls and telegrams to newspapers and to the Kennedy family.[53] They were heavily in favor of his remaining in office, and he was re-elected in 1970, with 62% of the vote, a margin of nearly a half million votes. Nonetheless, the incident severely damaged his national reputation and reputation for judgment; one analyst asked, "Can we really trust him if the Russians come over the ice cap? Can he make the kind of split-second decisions the astronauts had to make in their landing on the moon?" Before Chappaquiddick, public polls showed that a large majority expected Kennedy to run for the presidency in 1972. After the incident, he pledged not to run in 1972 and declined to serve as George McGovern's running mate that year. In 1974, he pledged not to run in 1976,[89][90] in part because of the renewed media interest in Chappaquiddick.[86][21]

In late 1979, Kennedy finally announced his candidacy for the presidency when he challenged the incumbent President Jimmy Carter for the Democratic nomination for the 1980 election. On November 4, 1979, CBS broadcast a one-hour television special, presented by Roger Mudd, titled Teddy. The program consisted of an interview with Kennedy interspersed with visual materials. Much of the show was devoted to the Chappaquiddick incident. During the interview, Mudd questioned Kennedy repeatedly about the incident and at one point directly accused him of lying.[91] During the interview, Kennedy also gave what one author described as an "incoherent and repetitive" answer to the question, "Why do you want to be President?"[92] He called the American-supported Shah of Iran "one of the most violent regimes in the history of mankind."[93] The program inflicted serious political damage on Kennedy.[92][93][94][95][96][97]

Carter alluded to the Chappaquiddick incident twice in five days, once declaring that he had not "panicked in the crisis."[98] Kennedy lost the Democratic nomination to Carter, who lost the general election to Ronald Reagan by a landslide, but Kennedy remained a senator until his death in 2009. He won all seven elections for the US Senate after the incident.

After Kennedy's death, Ed Klein, an editor for The New York Times Magazine and an American author, tabloid writer, and gossip columnist who had written about the Kennedys, stated that Kennedy asked people he met, "Have you heard any new jokes about Chappaquiddick?" Klein also said, "It's not that he didn't feel remorse about the death of Mary Jo Kopechne, but that he still always saw the other side of everything and the ridiculous side of things, too."[99]

The Dike Bridge became an unwanted tourist attraction[100][101][102][103][104] and the object of souvenir hunters.[105]

In an interview with Nance Lyons, dated 2008 and undertaken by the Edward M. Kennedy Institute, the former member of the "Boiler Room" team stated that the women present at Chappaquiddick had suffered both professionally and personally.[106]

In popular culture

The incident is the central subject of John Curran's film Chappaquiddick. The incident is fictionalized in the novel Black Water by Joyce Carol Oates.

Danny Devito's character Frank Reynolds in It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia claims to have played a major role in the event.

Notes

- ↑ Gargan's mother was the sister of Kennedy's mother. Gargan's mother died when he was six, and he was raised after that by Ted's parents. Joseph P. and Rose Kennedy.[16]

References

- ↑ "Chappaquiddick's Echoes". newyorker.com. Retrieved May 31, 2018.

- ↑ Wills, Garry (April 29, 1976). "The Real Reason Chappaquiddick Disqualifies Kennedy". Retrieved May 31, 2018 – via www.nybooks.com.

- ↑ Kelly, Michael (April 15, 2016). "Ted Kennedy on the Rocks". gq.com. Retrieved May 31, 2018.

- ↑ "Ted escapes car plunge; woman dies". Eugene Register-Guard. (Oregon). Associated Press. July 19, 1969. p. 1A.

- ↑ "Kennedy involved in fatality". Reading Eagle. Pennsylvania. UPI. July 20, 1969. p. 1.

- ↑ "Charge to Be Filed Against Kennedy". Eugene Register-Guard. (Oregon). Associated Press. July 20, 1969. p. 1A.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Putzel, Michael; Pyle, Richard (February 22, 1976). "Chappaquiddick (part 1)". Lakeland Ledger. (Florida). Associated Press. p. 1B.

- 1 2 3 Putzel, Michael; Pyle, Richard (February 29, 1976). "Chappaquiddick (part 2)". Lakeland Ledger. (Florida). Associated Press. p. 1B.

- 1 2 Jacoby, Jeff (July 24, 1994). "Unlike Kopechne, the questions have never died". The Day. (New London, Connecticut). (Boston Globe). p. C9.

- ↑ "Google Maps". Google Maps. Retrieved May 31, 2018.

- ↑ "Police file complaint against Kennedy". Eugene Register-Guard. (Oregon). Associated Press. July 20, 1969. p. 6A.

- ↑ "Complaint is filed against Kennedy". The Day. (New London, Connecticut). Associated Press. July 21, 1969. p. 11.

- ↑ NY Daily News: Kennedy's Legacy: Chappaquiddick was the end of one Ted Kennedy and the beginning of another

- ↑ Kessler, p. 418.

- 1 2 3 Bly, pp. 202–206.

- ↑ "Interview with Ann Gargan". Edward M. Kennedy Institute. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Wills, pp. 117–120.

- ↑ "John B. Crimmins, Long an Associate Of Edward Kennedy". NYTimes.com. May 31, 1977. Retrieved May 31, 2018.

- 1 2 "1969 Year in Review: Chappaquiddick". UPI Radio. 1969.

- ↑ Boyle, pp. 26–27, reported at Damore, p. 357.

- 1 2 Russell, Jenna (February 17, 2009). "Chapter 3: Chappaquiddick: Conflicted Ambitions, then, Chappaquiddick". The Boston Globe. Retrieved February 24, 2009.

- ↑ Exhumation hearing, p. 59, reported at Damore, p. 103.

- ↑ Boyle, p. 35, reported at Damore, p. 358.

- ↑ "Ted Kennedy's Chappaquiddick Incident: What Really Happened". history.com. Retrieved May 31, 2018.

- ↑ Banks, Charles Edward (May 31, 2018). "The History of Martha's Vineyard, Dukes County, Massachusetts: Town annals". G.H. Dean. Retrieved May 31, 2018 – via Google Books.

- ↑ "Chappaquiddick Island Stock Photos and Pictures - Getty Images". www.gettyimages.com. Retrieved May 31, 2018.

- ↑ "Notes from the Tackle Room: Poucha Pond". mvmagazine.com. December 1, 2015. Retrieved May 31, 2018.

- ↑ "Tow Truck Pulling Kennedy Car from Pond". gettyimages.com. Retrieved May 31, 2018.

- ↑ "Cape Pogue and Poucha Pond". vineyardgazette.com. Retrieved May 31, 2018.

- ↑ Boyle, pp. 56–60, reported at Damore, p. 360.

- 1 2 Anderson & Gibson, pp. 138–140.

- ↑ Anderson, Jack (September 1, 1969). "Diver Hints Kopechne Might Have Been Saved". St. Petersburg Times. p. 19A.

- 1 2 Boyle, p. 63, reported at Damore, p. 362.

- ↑ Boyle, p. 322, reported at Damore, p. 375.

- 1 2 Boyle, p. 80, reported at Damore, p. 363.

- 1 2 Boyle, p. 70, reported at Damore, p. 364.

- ↑ Cheshire, Maxine (March 13, 1980). "The Mysterious Helga Wagner". Retrieved May 31, 2018 – via www.washingtonpost.com.

- 1 2 "John Tunney Oral History (2007), Senator, California - Miller Center". millercenter.org. October 27, 2016. Retrieved May 31, 2018.

- ↑ "Chappaquiddick: The Unanswered Questions About Ted Kennedy's Fatal Crash - Reader's Digest". rd.com. April 6, 2018. Retrieved May 31, 2018.

- 1 2 "The End of Camelot". vanityfair.com. Retrieved May 31, 2018.

- ↑ http://jfk.hood.edu/Collection/Weisberg%20Subject%20Index%20Files/R%20Disk/Roberts%20Bruce/Item%2002.pdf

- ↑ Damore, p. 1.

- 1 2 Cutler, pp. 10, 42.

- ↑ Lange & DeWitt, pp. 40–41.

- 1 2 Olsen.

- ↑ Damore, p. 8.

- ↑ Cutler, p. 10.

- ↑ Anderson, Jack (September 25, 1969). "Chappaquiddick story". Nashua Telegraph. New Hampshire. (Bell-McClure). p. 4.

- ↑ The original statement left Kopechne's surname blank because Kennedy was unsure of its spelling, see Damore, p. 22.

- ↑ A photographic reproduction of the original typescript, which was Exhibit number 2 at the inquest, is available at Damore, p. 448.

- ↑ Damore, pp. 192–193.

- ↑ Damore, p. 193.

- 1 2 "Kennedy may quit, nation told on TV". The Day. (New London, Connecticut). Associated Press. July 26, 1969. p. 1.

- 1 2 "Kennedy puts political future on line". Eugene Register-Guard. (Oregon). Associated Press. July 26, 1969. p. 1A.

- ↑ The entire speech was inquest exhibit #3 and can be found at Damore, pp. 203–206.

- ↑ Damore, pp. 206, 208.

- ↑ John Farrar interview on the Howie Carr Show

- ↑ Lofton, John D., Jr. (June 17, 1975). "Kopechnes begin to have doubts about Chappaquiddick affair". Beaver County Times. Pennsylvania. (United Feature Syndicate). p. A7.

- ↑ Tiede, Tom (January 28, 1980). "Chappaquiddick diver slams Teddy". Southeast Missourian. Cape Girardeau. (NEA). p. 4.

- ↑ Kappel.

- ↑ Klein, p. 93.

- ↑ Kunen, James S.; Mathison, Dirk; Brown, S. Avery & Nugent, Tom (July 24, 1989). "Frustrated Grand Jurors Say It Was No Accident Ted Kennedy Got Off Easy". People. 32 (4).

- ↑ Tedrow & Tedrow, p. 36.

- ↑ Damore, p. 49.

- ↑ "Ted Kennedy joins hundreds at rites for accident victim". Eugene Register-Guard. (Oregon). Associated Press. July 22, 1969. p. 1A.

- ↑ "Kennedy family flies to Pennsylvania for funeral of woman accident victim". The Bulletin. (Bend, Oregon). UPI. July 22, 1969. p. 1.

- 1 2 3 Damore, p. vi.

- ↑ Damore, p. 307.

- ↑ "Dinis Says Blood On Mary Jo's Body". Boston Herald Traveler. September 16, 1969.

- ↑ Tedrow, Richard L., and Thomas L. (1980). Death at Chappaquiddick. Pelican Publishing. pp. 98–99. ISBN 1455603406.

- ↑ "Examiner testifies against kopechne autopsy". Daily Kent Stater. October 22, 1969.

- ↑ Damore, p. 343.

- ↑ Chappaquiddick Inquest - Boston.com

- ↑ Trotta, p. 184.

- 1 2 Bly, p. 213.

- ↑ Dinis, pp. 391–392.

- ↑ Dinis, p. 392.

- 1 2 Bly, p. 216.

- 1 2 3 4 "End of the Affair". Time. April 20, 1970. Retrieved August 3, 2008.

- ↑ Press release of Registrar McLaughlin, July 23, 1969, reported at Damore, p. 165.

- ↑ Facsimiles of the hearing report and the letter are at Damore, pp. 449–450.

- ↑ Taraborrelli, pp. 395, 396, 399.

- ↑ Taraborrelli, p. 192.

- ↑ James, Susan Donaldson (August 26, 2009). "Chappaquiddick: No Profile in Kennedy Courage". ABC News. Retrieved August 26, 2009.

- ↑ Barnard, Peter (July 22, 1994). "One Giant Leap Backwards". The Times. London.

- 1 2 "The Mysteries of Chappaquiddick". Time. August 1, 1969. Archived from the original on August 31, 2009.

- ↑ Lofton, John D., Jr. (November 19, 1973). "Suit settled on Kennedy spoof". Victoria Advocate. Texas. (Los Angeles Times / Washington Post News Service). p. 4A.

- ↑ "Lampoon's Surrender". Time. November 12, 1973. Retrieved September 10, 2006.

- ↑ Gaines, Richard (September 23, 1974). "Kennedy 'won't run,' says decision final". Eugene Register-Guard. (Oregon). UPI. p. 1A.

- ↑ "Kennedy rejects race". Spokane Daily Chronicle. (Washington). Associated Press. September 23, 1974. p. 1.

- ↑ Barry, p. 182.

- 1 2 Allis, Sam (February 18, 2009). "Chapter 4: Sailing into the Wind: Losing a Quest for the Top, Finding a new Freedom". The Boston Globe. Retrieved March 10, 2009.

- 1 2 Boller, p. 355.

- ↑ Barry, p. 188.

- ↑ Baughman, p. 169.

- ↑ Jamieson, pp. 379–381.

- ↑ Buchanan, Pat (July 23, 1979). "Why Chappaquiddick haunts Kennedy". Ocala Star-Banner. Florida. p. 4A.

- ↑ "Nation: Once Again, Chappaquiddick". Time. October 8, 1979. Retrieved August 26, 2009.

- ↑ Rehm, Diane (August 26, 2009). "Reflections on Sen. Kennedy". The Diane Rehm Show. Washington, DC: WAMU-FM. Event occurs at 29:45. Archived from the original on September 30, 2011. Retrieved August 28, 2009.

- ↑ "The bridge on Chappaquiddick". Nashua Telegraph. New Hampshire. (AP photo). July 12, 1974. p. 13.

- ↑ "Decision near on bridge at Chappaquiddick". Pittsburgh Press. UPI. June 21, 1981. p. A-4.

- ↑ "Some say Chappaquiddick bridge is nuisance". The Day. New London, Connecticut. Associated Press. August 29, 1983. p. 5.

- ↑ Trott, Robert W. (July 17, 1989). "Bitter memories and a rotting bridge". Spokesman-Review. Spokane, Washington. Associated Press. p. A5.

- ↑ "Chappaquiddick: bridge abandoned but story lives". The Hour. Norwalk, Connecticut. Associated Press. July 18, 1994. p. 24.

- ↑ "A bridge to the past". Milwaukee Journal. wire services. July 18, 1994. p. A3.

- ↑ "Interview with Nance Lyons". www.emkinstitute.org. Retrieved May 31, 2018.

Sources

- Anderson, Jack & Gibson, Daryl (1999). Peace, War, and Politics: An Eyewitness Account. New York: Forge. ISBN 0-312-87497-9.

- Barry, Ann Marie. Visual Intelligence: Perception, Image, and Manipulation in Visual Communication. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. ISBN 0-7914-3435-4.

- Baughman, James L. The Republic of Mass Culture: Journalism, Filmmaking, and Broadcasting in America since 1941. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-8315-6.

- Bly, Nellie (1996). The Kennedy Men: Three Generations of Sex, Scandal, and Secrets. New York: Kensington Books. ISBN 1-57566-106-3.

- Boller, Paul F. (2004). Presidential Campaigns: From George Washington to George W. Bush. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-516716-3.

- Boyle, James A. (1970). Inquest into the death of Mary Jo Kopechne. Edgartown, MA: Edgartown District Court. OCLC 180774589.

- Cutler, R. B. (1980). You, the Jury ... In Re: Chappaquiddick. Danvers, MA: Bett's & Mirror Press. OCLC 5790437.

- Damore, Leo (1989). Senatorial Privilege: The Chappaquiddick Cover-up. New York: Dell Publishing. ISBN 0-440-20416-X.

- Jamieson, Kathleen Hall (1996). Packaging The Presidency: A History and Criticism of Presidential Campaign Advertising (3rd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-508942-1.

- Kappel, Kenneth R. (1989). Chappaquiddick Revealed: What Really Happened. New York: Shapolsky Publishers. ISBN 9780944007648.

- Kessler, Ronald (1996). The Sins of the Father: Joseph p. Kennedy and the Dynasty He Founded. Hachette Book Group USA (Warner Books). ISBN 0-446-60384-8.

- Klein, Edward (2009). Ted Kennedy: The Dream That Never Died. New York: Crown Publishers. ISBN 978-0-307-45103-3.

- Lange, James E. T. & DeWitt, K. Jr. (1992). Chappaquiddick: The Real Story. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-08749-7.

- Olsen, Jack (1970). The Bridge at Chappaquiddick. Boston: Little, Brown. OCLC 55947.

- Taraborrelli, J. Randy (2000). Jackie, Ethel, Joan: Women of Camelot. Warner Books. ISBN 0-446-52426-3.

- Tedrow, Thomas L. & Tedrow, Richard L. (1980). Death at Chappquiddick. Pelican Publishing. p. 36. ISBN 0-88289-249-5.

- Trotta, Liz (1994). Fighting for Air: In the Trenches With Television News. Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press. ISBN 0-8262-0952-1.

- Wills, Gary (2002). The Kennedy Imprisonment: A Meditation on Power (1st Mariner Books ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-618-13443-3.

Further reading

- Burns, James M. (1976). Edward Kennedy and the Camelot Legacy. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-07501-X.

- Caruana, Stephanie (2006). The Gemstone File: A Memoir. Victoria, BC: Trafford. ISBN 1-4120-6137-7.

- Hastings, H. Don (1969). The Ted Kennedy Episode. Dallas: Reliable Press. OCLC 16841243.

- Jones, Richard E. (1979). The Chappaquiddick Inquest: The Complete Transcript of the Inquest into the Death of Mary Jo Kopechne. Pittsford, NY: Lynn Publications. OCLC 11807998.

- Knight, Peter, ed. (2003). Conspiracy Theories in American History: An Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC Clio. ISBN 1-57607-812-4.

- Oates, Joyce C. (1992). Black Water. New York: E. P. Dutton. ISBN 0-525-93455-3. (fictional treatment).

- Reybold, Malcolm (1975). The Inspector's Opinion: The Chappaquiddick Incident. New York: Saturday Review Press. ISBN 9780841503991.

- Rust, Zad (1971). Teddy Bare: The Last of the Kennedy Clan. Boston: Western Islands. OCLC 147764.

This book follows the circumstances of the Chappaquiddick tragedy, from its mysterious beginning to its squalid conclusion ... before a terrorized grand jury ..." – Prologue to the book, p. vii

- Sherrill, Robert (1976). The Last Kennedy. New York: Dial Press. ISBN 9780803744196.

- Spitz, Daniel J. (2006). "Investigation of Bodies in Water". In Spitz, Werner U.; Spitz, Daniel J. & Fisher, Russell S. Spitz and Fisher's Medicolegal Investigation of Death. Guideline for the Application of Pathology to Crime Investigations (4th ed.). Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas. pp. 846–881. ISBN 9780398075446.

- Tedrow, Thomas L. (1979). Death at Chappaquiddick. New Orleans: Pelican. ISBN 0-88289-249-5.

- Willis, Larryann C. (1980). Chappaquiddick Decision. Portland, OR: Better Books Publisher. OCLC 6666517.

External links

- FBI Chappaquiddick investigation files

- Chappaquiddick Inquest - Boston.com

- Edward M. Kennedy's Address to the People of Massachusetts on Chappaquiddick, broadcast nationally, from Joseph P. Kennedy's home, on 25 July 1969

- Photos of 1969 Chappaquiddick incident - New Haven Register

- Collection of newspaper articles covering the incident

Coordinates: 41°22′24.0″N 70°27′13.3″W / 41.373333°N 70.453694°W